The magenta sunset colors the Sound as if a watercolor painting. Uummannaq Fjord, 2016. —Denis Defibaugh photo

By Bruce A. Austin

COOPERSTOWN, N.Y. – American Modernist artist and adventurer Rockwell Kent set off for Greenland on a 33-foot sailboat in 1929 “to experience the Far North at its spectacular worst.”

Kent’s sailboat dragged anchor in a fjord south of Nuuk, the nation’s capital, breaking up on the rocks during a midnight storm. But bad luck became good while waiting for boat repairs: Kent made his first forays across ice-scoured rocks and quickly understood that nothing could stop him from returning to this place at and above the Arctic Circle.

Inspired by a rarely seen and almost never published collection of photographs Kent made while in Greenland, American photographer Denis Defibaugh retraced Kent’s journey almost 90 years later.

Synthesizing photographic methods separated by nearly a century, “North by Nuuk” offers sublime, insightful and intimate views of Greenland. Defibaugh’s photographs of mostly untouched remote Arctic communities present the nation’s primal and social landscapes, its indigenous people, and their traditions and culture.

“North by Nuuk: Greenland after Rockwell Kent,” an exhibition featuring 52 of Defibaugh’s images and a dozen of Kent’s works will be on view at the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown until December 31.

Each spring when the weather warms up, young and old alike play the baseball-like game of rounders. Illorsuit, 2016. —Denis Defibaugh photo

Kent’s Greenland

“I crave snow-topped mountains, dreary wastes and the cruel North Sea with its far horizons at the edge of the world,” Kent wrote earlier in Wilderness, his Alaska journal.

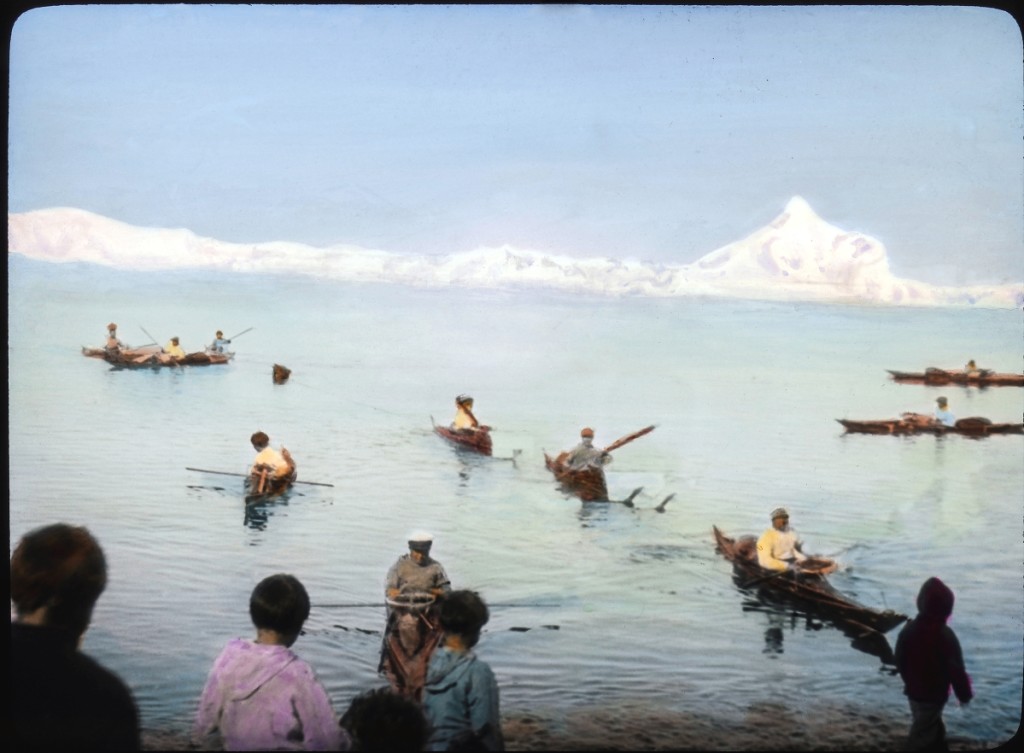

On his 1931 return trip to Greenland, ultimately becoming a more than one-year stay with a return in 1934-35, Kent made photographs with a 35mm Leica, in addition to painting and drawing. He sent his negatives to the Joseph Hawkes Studio in New York City, where they were made into 3-by-2-inch positive black and white glass lantern slides and later hand colored. The slides were made for presentations Kent delivered to the American public as part of his illustrated lecture tours. In 1933, Kent visited 47 US cities, giving “PowerPoint” lectures at each.

A magnetic speaker, his romanticized adventure story made a significant impact on listeners.

“The Rockwell Kent lecture was splendid [and] his pictures delightful,” the Women’s Club of Evanston, Ill., reported. “Our clubhouse was full and we turned away a number of people.” But aside from lecture audiences, few saw Kent’s slides.

Dorthe Simionsin shows her deformed finger caused by a life of sewing seal skins. Uummannaq, 2016.

—Denis Defibaugh photo

Today, the mostly undisturbed slide collection is stored in small wooden boxes, housed in the Rockwell Kent Collection at the University Art Museum of the State University of New York, Plattsburgh.

Once Defibaugh learned of the collection, he became determined to follow Kent’s travels. For 16 months he immersed himself in Greenland’s environment and culture. The result: “a rare visual resource for historians of the Arctic as well as of modern American art,” wrote Jake Milgram Wien, author of Rockwell Kent: The Mythic and the Modern, in his review of the “North by Nuuk” book for Arctic, a scientific journal.

Defibaugh “developed a meaningful collaboration with the study communities as I participated in daily life, building relationships that enabled a representative version of how reality is constructed.”

Inspiring Art In Uummannaq And Illorsuit

In 1931, Kent met with two of Greenland’s most famous explorers: Knut Rasmussen and Peter Freuchen. They introduced him to Illorsuit, the only village on Ubekendt Eyland – Unknown Island. Nearly 300 miles north of the Arctic Circle, Illorsuit is located in an extensive fjord area of central west Greenland where glaciers line its jagged coast.

Uummannaq is the scenic doorway into Illorsuit, as much for Kent as Defibaugh. The town is dominated by the massive, heart-shaped Mount Uummannaq that can be seen from Illorsuit, about 60 miles northwest.

“Uummannaq is fantastic, with amazing views,” resident Ann Andreasen told Defibaugh in 2016. “Our iceberg moves every day and is a piece of abstract art,” she said.

A magenta sunset is the backdrop for one Defibaugh image, a sharply peaked house at foreground with an iceberg at Uummannaq Fjord in between. Clothes air dry in the middle of winter in another photograph, a blue-green ocean moat separates them from the stark glacier background.

Illorsuit became Kent’s physical and spiritual canvas. “It was perhaps the happiest and certainly most productive [time] of my life,” he later wrote in his book, Greenland Journal. Defibaugh spent three months photographing the community.

Pujunnguaq Hammond and David Nielsen dog sledging to their fishing holes. Temperature is about -10 degrees Farenheit. Uummannaq Fjord, 2017. —Denis Defibaugh photo

Fenimore Art Museum visitors are greeted by Defibaugh’s 24-foot panorama of the 80-mile-long mountain range bordering Illorsuit Sound. The photograph’s size, colors, and composition, an homage to Kent’s art.

Illorsuit’s expansive, horseshoe-shaped, black sand beach on the pristine fjord, invites a vision of an exotic tourist destination. But the remote community remains a quiet settlement with no cars or roads, and still has no running water.

Winter’s arrival means Illorsuit will not see a ship with cargo and fresh produce from December until April, sometimes May.

“We are not that many here,” resident Erik Qvist told Defibaugh. Illorsuit’s population numbered about 165 when Kent arrived in 1931; by 2016, it had shrunk by half. A fishing community, seal and whale are still hunted for food: for Illorsuit’s people and their dogs.

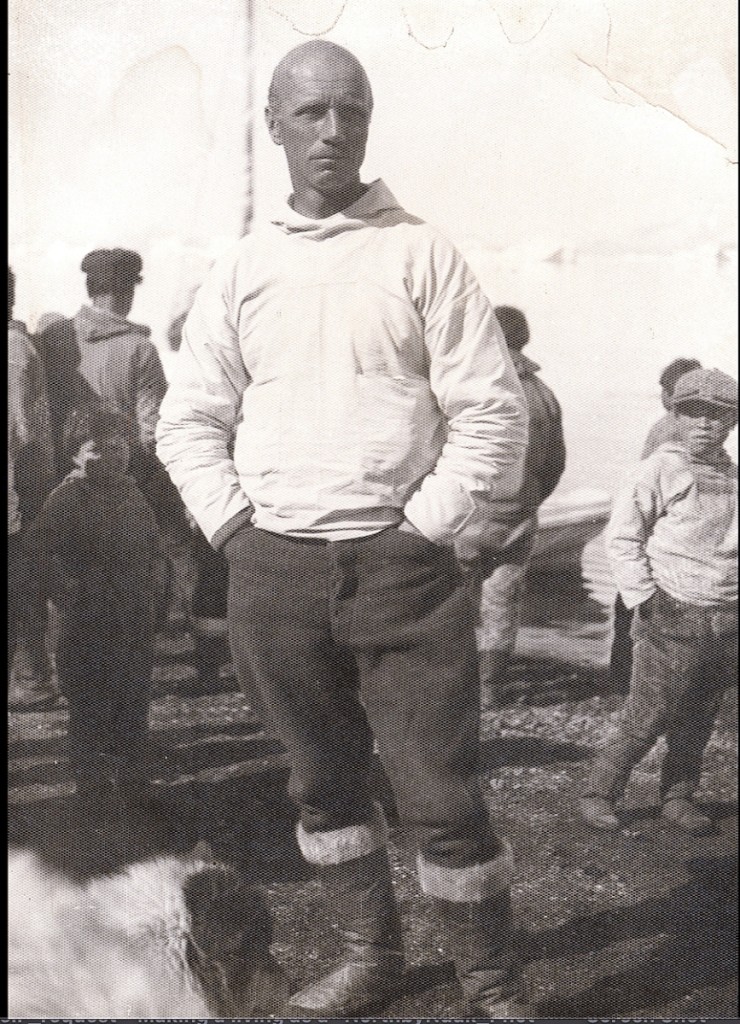

Photo of Rockwell Kent wearing anorak and seal skin boots, possibly on the Illorsuit beach with Inuit residence, circa 1932.

—Kent photos

Defibaugh photographed Mathias Nielsen’s eight-hour day fishing for halibut on the Illorsuit Sound; he caught more than 2,000 pounds. In another photo, halibut and capelin hang from traditional drying racks overnight, frozen flags in the Arctic air.

During the 1930s and under Danish colonial rule, Greenland was a “closed” country: non-Danes could not enter without governmental permission. Greenlanders would not have known any foreigners except those rare explorers who traveled along its coasts in the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries.

Illorsuit citizens responded favorably to Kent. He was “very friendly…[and] seemed kindly,” one remembered, and “soon became like one of our own citizens.” Kent recorded information about people and places in his journal. His camera memorialized impressions. But Greenlanders’ first-hand accounts about Kent are scarce.

Samuel Moller’s 1932 article for one of the two national periodicals, Avangnamiok, is the exception. A careful observer, Moller assessed Kent’s carpentry talent (“very skilled, very beautiful”), sports ability (“we took him down many times, he was not well prepared”), and artistry (“someone whose talents cannot be ignored, [he] often painted very big scenes, and infrequently, small ones”).

Moller’s complete article, translated to English, is reproduced in the North by Nuuk book accompanying the exhibition.

David in background and Martin Zeeb. Both helped Kent. David took care of his dogs and hunted for him, circa 1932.

—Kent photos

Photographing Greenland In 1931 And 2016

Gretel Ehrlich describes Kent’s photographs as “casual snapshots” in her foreword to the North by Nuuk book. The photos, she writes, “reveal the complete ease with which [Kent] slipped into Greenlandic culture.” Participant observation with a recording device, ethnographic anthropologists might say.

Both Kent and Defibaugh offer vignettes of Greenlandic life. Kent’s are “homey and affectionate” and preserved on glass; Defibaugh’s digital images “capture both the universal and the particular, the abstract and the concrete, and activates the five senses,” Wien wrote.

Sometimes their work thematically overlaps, other times diverging sharply. Compare, for instance, Kent’s image of dogs pulling his driverless sledge (sled) across a frozen fjord to Defibaugh’s nearly identically fanned out group of nine dogs tugging a similarly designed sledge to a fishing hole, but now with two hunters at foreground.

Defibaugh depicts a mixed group of young and old playing a baseball-like game of rounders on a grassy spring field in one photograph. Motionless residents posed for Kent before sharply peaked Illorsuit buildings for a 1932 photo; most of the buildings still stand and remain in use.

Illorsuit’s cemetery on the southern headlands in 2016 is far more crowded than the half dozen crosses propped up by mounds of rocks piled atop still larger rocks pictured in 1932. Defibaugh’s treatment is nearly monochromatic, while Kent positions the crosses beneath a wide, pink horizon dissolving into a blue expanse of sky.

Across Greenland’s sweeping landscapes and broad horizons, enormous mountains and icebergs overwhelm human figures. Defibaugh photographed a couple pushing their pram across a glacial expanse of white – tiny dots amid a bleak environment. The extraordinary, sometimes unforgiving extreme environment of imposing splendor, shapes and at least occasionally is shaped by its inhabitants. The soul of the country, it is dangerous yet inviting.

“North by Nuuk” is an engaging view of change and continuity. “Much has changed,” Ehrlich writes, “much is the same.” While the historic nation is impacted by modernity, Defibaugh’s photographs reveal it is held together by community and the life and values their culture prescribes.

Denis Defibaugh is emeritus professor, School of Photographic Arts and Science, Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT). Photographer-author of The Day of the Dead (Texas Christian University Press, 2007), he has presented more than 30 solo museum and gallery exhibitions. The documentary project was funded by the National Science Foundation. The exhibition is accompanied by a 16-minute video slide show of Rockwell Kent’s 1930s lantern slides with voiceover from a 1956 Kent interview.

The exhibition catalog is published by RIT and can be purchased at www.rit.edu/press/north-by-nuuk.

The Fenimore Art Museum is at 5798 NY-80 in Cooperstown. For information, 607-547-1400 or www.fenimoreartmuseum.org.