Stanley B. Burns, MD, FACS is an ophthalmologist and research professor of medicine and psychiatry and professor of medical humanities at New York University: Langone Medical Center. He is also an internationally distinguished author, curator, historian, collector and archivist. In 1975, he began collecting historic photography with an emphasis on unique photographs not available anywhere else – a collection of more than one million vintage photographs (1840-1950). More recently, he has turned his attention to publishing images from a collection of photographs of the African American working and middle classes. Picturing Freedom, a 272-page celebration of African American life, chronicles the photographic history of the pride and joy of car ownership. We climbed into the passenger seat with Burns at the wheel to explore this photographic paean to freedom and travel.

Congratulations on publishing this wonderful book. What gave you the notion to write it and what is your goal in bringing it out?

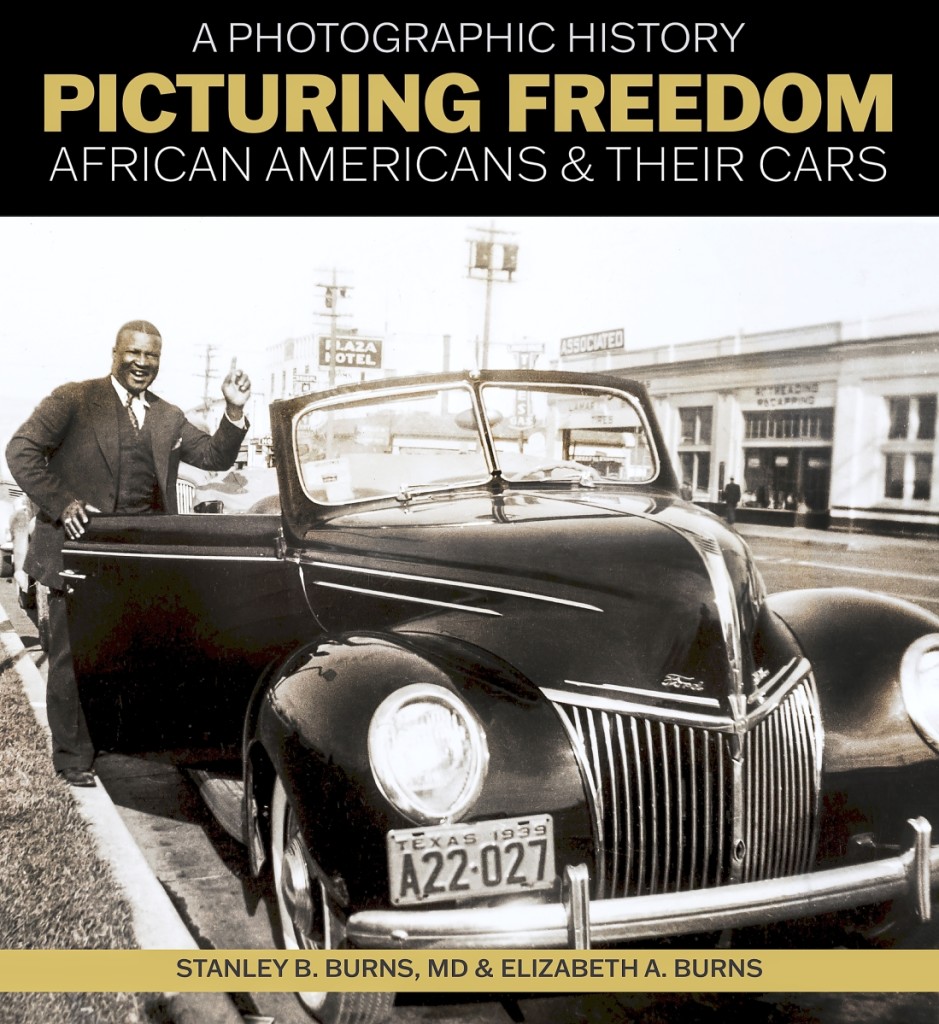

In 1977, I established the Burns Archive to share my discoveries through publications and exhibitions, focusing on unexplored aspects of culture. I was inspired to present this aspect of American life to raise social consciousness. These photographs add to the visual narrative of our culture and document the significance of cars in African American history. As I accumulated these photographs, I recognized that together they reveal the evolution of African American life, fashion and cars. The car was a source of immense pride for those who could purchase one and was purposely and proudly photographed. The personal images in this book vividly illustrate the pride and joy of car ownership.

With more than 450 photographs, we would imagine that the majority are vernacular but perhaps a good many are professional as well?

All the photographs in this compilation are snapshots taken in Black communities by a family member or a friend. The only professional photographs in the book were those taken in studios in the first decade of the Twentieth Century, as cars were a common prop. By 1920, the personal camera was ubiquitous, and people were documenting their own lives and portraying themselves as they wanted to be seen and remembered.

What was your most striking revelation as you unearthed these photographs?

Many of the photographs transcend the snapshot genre and are masterpieces of photography. They are iconic images of achieving success in America.

African American historical photographs have performed with strength at auction, such as the 1864 carte de visite of American abolitionist and women’s rights activist Sojourner Truth that sold for a record $13,750 at Hindman’s in February and the $32,500 auction record price realized at Swann Galleries recently for McPherson & Oliver’s 1863 photograph “The Scourged Back.” Your collection of images, however, seems to document Black women and men striving to succeed in a racist society.

When I began collecting historic photographs in 1975, I was stunned by the number of derogatory African American images for sale and the emphasis on racist photography. Seeing so many derogatory images, I decided I would collect photographs to show an accurate view of African American life. My collection spans the entirety of the African American experience. My objective through publications and exhibitions is to present a picture that increases understanding and changes attitudes. The photographs in this book celebrate Black success.

The book is a collaboration with your daughter, Elizabeth A. Burns, her sixth book and your 50th. How did you divide up the work?

I collect the photographs and recognize their value in history and culture. Liz creates the layout and design and oversees printing and production. We work together to write the histories. We have been collaborating for years, and I am thrilled that Liz is carrying on my vision of using historical photography to shape contemporary perspective.

Why do think owning an automobile was a life-changing achievement for many African Americans?

It offered many freedoms – the freedom to travel, the freedom to work further from home, the freedom to visit family and friends, the freedom to avoid Jim Crow laws and the freedom to migrate. For African American women, most restricted to the home or farm, cars were particularly prized. They allowed for independence and freedom at all times of the day to visit friends and relatives, socialize or work outside the home. The car was unequivocal evidence of Black success and an important symbol of status in a country that had long fought their advancement in every area.

While offering an escape from Jim Crowism, owning and operating a car even today can spark racist backlash, as in “driving while Black.” Can you tell us about The Green Book , which in the 1930s through the 1960s contained businesses that provided services to African Americans as they traveled by car in the United States?

Traveling in much of the United States, especially the restricted Jim Crow South, until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of the mid-1960s was very difficult. Sundown towns, localities with written or unwritten rules banning African Americans within city limits at night, were found all across the country from Maine to California. The lack of available services was a major issue for Black drivers, and considerations had to be made to travel safely. Motorists would pack their own food with the understanding that restaurants along the route would refuse to serve them. Blankets were frequently taken as well, as accommodations could be hard to find. With nowhere to stay, sleep deprivation added another layer of complexity and danger. In 1936, Victor Green developed a guide to help African Americans travel without fear. He received information from a network of Black letter carriers across the country to create his lists of gas stations, garages, restaurants and overnight accommodations. The Green Book also contained businesses that provided services to African Americans; most were Black-owned.

What comprises the Burns Archive?

The Burns Archive and Collection contains more than one million historic photographs from the birth of photography (1839) through the modern age. It is best known for providing photographic evidence of forgotten, unseen and disquieting aspects of history and culture. Many of the photographs are one-of-a-kind and not available anywhere else. The archive houses unparalleled photographic collections of early medicine, memorialization, crime, racism, Judaica and the African American experience. Over the past 47 years, thousands of publishers, curators, authors, researchers, artists and filmmakers have utilized this unique source of visual documentation.

The collection contains the full range of photographic formats, including thousands of daguerreotypes and ambrotypes (1840-1860), tintypes (1860-1895), cartes de visites (1858-1870), cabinet cards (1870-1900), large format silver-gelatin prints (1870-1920), stereoviews (1860-1920), real photo postcards (1908-1940), as well as snapshots (1890-2000). Hundreds of albums depict family life, occupations, military experience, travel and industry. The highlight of the Burns Collection is four albums with 960 photographs of Civil War wounded soldiers taken by US Army Surgeon Reed Bontecou in 1864-65. These images have been requested more than any other in the collection, and 48 will be exhibited in the Reina Sofía National Art Museum, Madrid, Spain, in November.

The Burns African American Collection focuses on working and middle-class life and culture and covers a wide spectrum of the African American experience from the institution of slavery through the Civil Rights era. The emphasis of the collection is on vernacular photography, images produced in the Black community for the Black community. The collection includes early works by African American daguerreotypists Ball, Washington and Goodridge and thousands of studio portraits from 1845 to 1960. The collection contains images of enslaved people, freemen and freewomen, and Civil War contraband; occupations and agriculture, especially cotton and turpentine; everyday life, churches, schools, organizations, and home and night life; racism, the KKK, lynching and vigilantism; crime, punishment and prisons; military service; and civil rights.

What started you off on your journey of collecting historic photographs?

Since childhood, I have been fascinated by history. I initially collected stamps as a country’s history is conveyed on its postage. In 1950, at age 12, I became interested in the Civil War. Our next-door neighbor’s father fought in the 143rd New York Infantry and he often showed me his father’s uniform, equipment and guns. In college, I discovered Lossing’s 16-volume Photographic History of the Civil War with Mathew Brady’s photographs and was mesmerized by the images.

In 1962, while at medical school in Syracuse, I began collecting Sixteenth-Nineteenth Century arms and armor, which were available at flea and antiques markets. I concentrated on various weapon mechanisms and projectiles as wars were often determined by an advance in weapon mechanisms and the tactics they triggered. I was interested in photography as documentary evidence and photographed my medical school years. My efforts were recognized and I was elected photographic editor of the yearbook. After moving to California in 1964, I began displaying my collections of Sixteenth-Eighteenth Century pistol mechanisms at antique gun shows and frequently won prizes. At these shows, photographs often accompanied displays, mostly Western images and Native Americans.

In the late-1960s, medical history became a significant interest, and I joined various historical societies. In 1975, a friend and fellow arms collector Peter Buxton showed me a daguerreotype of a South American native with a tumor of the jaw. He told me about the recent availability and emerging market of early photography and the frequent antique photograph markets being established. He opened my eyes to the availability of historic photography; I bought that daguerreotype. I sold my arms collection and, with the funds, aggressively began acquiring photographs, attending weekly shows, antiques markets and auctions. I also bought established collections. The Newtown Bee was my guide to the markets and I regularly advertised to buy medical photographs and daguerreotypes. I had my first major exhibition in 1978. By 1979, my collection was showcased in the Time-Life Encyclopedia of Collectibles as the leading private historic photography collection. Since then, I have written 50 books and more than 1,100 journal articles and curated dozens of exhibitions on historical photography.

What was your first car? And what would be your dream ride?

My first car was a 1962 Peugeot 404, and my dream car is a 1938 Packard Twelve Sedan Convertible.

Tell us about your experience as historical advisor to the HBO historical medical series The Knick and PBS Civil War series Mercy Street.

Liz and I were on both sets almost every day, providing guidance and historical accuracy in the recreation of turn-of-the-century and Civil War medicine. I turned the actors into physicians/surgeons and advised on set for all medical procedures and operative scenes. We worked closely with the Art, Props, and FX Departments, utilizing Burns Archive photographs to perfect details of the periods. It was an honor to work with director Steven Soderberg and teach Clive Owen and André Holland how to operate.

When you’re not collecting, consulting, lecturing, creating exhibits and writing books, what draws your interest?

Travel – especially taking long cruises to exotic ports.

-W.A. Demers

[Ed. note: How to purchase Picturing Freedom: https://www.burnsarchive.com/picturingfreedom or at the burnsarchive.com online shop.]