After a lengthy search for an assistant curator, Historic New England appointed Dr Erica Lome to the position last March. Lome has not stopped working since her graduation from the Bard Graduate Center in 2015, then moving on to the University of Delaware and earning her doctoral degree in 2020. She represents a new generation of professional scholars, slowly but surely filling the ranks in the world of antiques and the arts. Before Historic New England, Lome was instrumental in the reinstallation of the new permanent galleries at the Concord Museum, presenting hundreds of objects that witnessed the Battles of Lexington and Concord in the “Shot Heard Round The World” exhibit. She also curated the museum’s current exhibition, “Alive With Birds: William Brewster In Concord.” Lome also specializes in Colonial Revival furniture, with particular focus on immigrant and African American craftspeople. In April, Lome visited Kentucky in search of Colonial Revival furniture by master African American craftsman Milton Paul (1921-88). Just a few days after, she was marching with Minutemen at the Patriots’ Day reenactment. We asked about her experiences, favorite furniture and what’s next for Historic New England.

Congratulations on your new associate curator position with Historic New England! Could you favor our readers with some highlights from your background?

Thank you! I am thrilled to join Historic New England and work with colleagues I’ve long admired. I came to Historic New England after two years at the Concord Museum, where I served as the Peggy N. Gerry curatorial associate, a position sponsored by the Decorative Arts Trust. Before that, I obtained my PhD through the American Civilization Program at the University of Delaware, during which I completed graduate fellowships at Winterthur Museum, Nemours Estate and the Boston Furniture Archive. I have a master of arts degree in Decorative Arts, Design History and Material Culture from the Bard Graduate Center in New York and have also worked for the New-York Historical Society, the Museum of Arts and Design and Bonhams.

I feel fortunate to have had these rich and varied experiences; each informed my practice as a historian and museum professional.

Colonial Revival cupboard, Wallace Nutting (1861-1941), 1920-30. Museum purchase, Historic New England.

What first attracted you to the study of decorative arts and material culture?

When I was an undergraduate, I worked as a seasonal interpreter at The Mount, The Edith Wharton Estate in Lenox, Mass. I had previously enjoyed Wharton as a writer but being in her home unlocked her for me as a person. The Mount was Wharton’s rebuttal to the established conventions of Gilded Age taste as outlined in her book The Decoration of Houses (1897), wherein she advocated for a return to classical proportions, symmetry and simplicity in design and architecture. Though Wharton only inhabited The Mount for a short time, she imbued every inch of space with her passion and attention to detail. I witnessed how objects and space could become powerful interpretive tools in the hands of a skilled guide. I nurtured my interests in material culture and the public humanities in school, and by the time I began my doctoral program at the University of Delaware, I knew I wanted to apply my academic training towards humanizing and making accessible the individuals and subjects that, for many, reside in a remote past.

Your dissertation focused on Colonial Revival furniture, tell us more about your interest in that style.

My dissertation was inspired by a very relatable situation: for decades, my parents have been the caretakers of my great-grandmother’s Colonial Revival furniture suite, which previously furnished her Upper West Side apartment in New York City. My great-grandparents were Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe and the acquisition of these beautiful reproductions of Chippendale and Hepplewhite furniture were a meaningful investment in their new, upwardly mobile lives. These pieces held such sentimental value to four family that my grandmother and mother could not bear to let them go. I will eventually inherit these pieces, and I hope by that point I have enough space to display them!

I was curious: why did these things matter so much to my family? What meanings did my great-grandmother and other newly minted Americans derive from the acquisition and display of this style of furniture in their homes? Nicknamed “Heirlooms of Tomorrow” for their perceived timelessness and durability, reproductions of antiques were highly successful commercial products and a staple of the middle-class American interior for most of the Twentieth Century. But despite their ubiquity, shockingly little research had been done to understand these objects on their own merits. My dissertation therefore explores the production, promotion and consumption of Colonial Revival furniture from 1890 to 1945.

Historic New England was a fantastic resource for my research. In addition to being historically rooted in the preservation movement, we have a fabulous collection of Colonial Revival furniture, ceramics, textiles and ephemera. I feel extremely fortunate to get to share my passion for the Colonial Revival – and all its complexity – with our members and the public.

Photograph of Olof Althin (1859-1920) in his cabinet shop in Boston.

Courtesy of the Althin family.

Another concentration of your work has been immigrant craftspeople and their contribution to American material culture, what drew you to that subject?

I am fascinated by what went on “behind the scenes” of the Colonial Revival movement, especially in the antiques trade. By the late Nineteenth Century, the decline in the apprenticeship system and the rise of industrialized furniture manufacture led to fewer cabinetmakers with the skills to repair, restore and even reproduce antique furniture. European immigrants ended up filling most of these roles and collaborated with collectors, dealers and curators to establish the field of American decorative arts as we know it today.

While many of these cabinetmakers were Jewish, a fact that first drew me to this topic, one of them was Swedish-born woodworker named Olof Althin who ran a small but very successful cabinet shop in Boston at the turn of the Twentieth Century. Althin made custom furniture in various period styles, but he was also the contractor for notable antique collectors Charles Hitchcock Tyler and H. Eugene Bolles. Althin is very likely responsible for restoring the Seventeenth Century pieces from those two collectors on view today at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. By the end of his career, Althin claimed to know more about early American furniture than any dealer or appraiser!

To my delight, Althin left behind business records, designs, furniture, woodworking tools, personal effects and even his workbench. I recently curated an exhibition on his work at the American Swedish Historical Museum, and I’m currently working on a companion monograph that explores his creative and industrious career in Boston.

Historic New England also offers plenty of opportunities to engage with the work of immigrant craft and labor in the early Twentieth Century, and I am looking forward to promoting those stories as part of my new role in this organization?

What are the most memorable experiences you’ve had with an artifact or object?

When I was researching for my dissertation, I came across an article on the NAACP magazine The Crisis about the Paul Laurence Dunbar High School in Lexington, Ky. Since the 1920s, Dunbar’s cabinetmaking program trained Black youth to make beautiful furniture by hand, setting them up for economic success within their communities. One of the graduates of this program was Milton Paul, who went on to become a celebrated cabinetmaker in Lexington and was especially famous for his Colonial Revival mirrors. These mirrors remain treasured heirlooms in Kentucky, but very little is known about Milton Paul himself.

I recently traveled to Lexington to dig into the local history archives and speak to former dealers and clients, as well as members of Paul’s family. I ended up learning so much, including the fact that Milton Paul signed his mirrors by carving a small “x” into the back of the frame. This was because some unsavory dealers had previously removed the paper backing with his handwritten signature and passed off the mirrors as genuine antiques. By carving that “x” into the frame, Paul ensured that his identity could not be erased going forward.

I had heard rumors that Milton Paul produced a reproduction mirror for a historic property in Lexington, but nobody knew which one. I was determined to track it down. With only a day left on my trip, I stopped by a house museum which had been renovated in the 1950s and spied a lovely neoclassical mirror in the front hall. I asked one of the interpreters if we could examine the back and, lo and behold, there was the “x”! I was so happy to make this attribution and share my research, especially as it resulted in renewed attention to this local artisan and the larger community of Black cabinetmakers in the city.

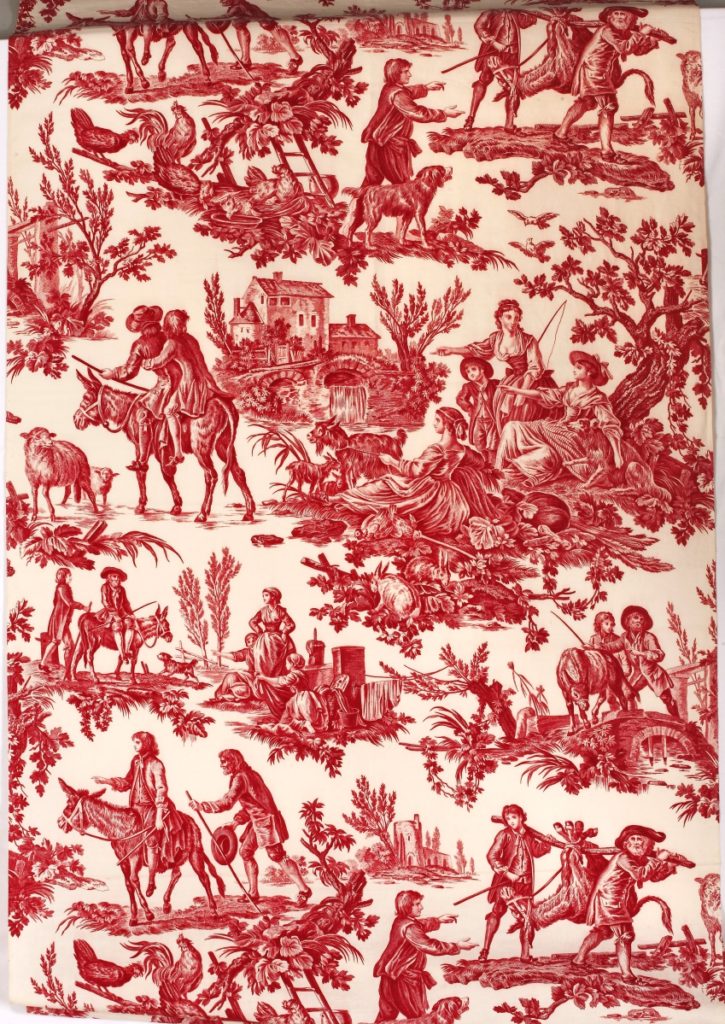

Window hangings used at the Codman House and in Edith Wharton’s boudoir at The Mount. Bequest of Dorothy S.F.M. Codman, Historic New England.

What can we expect from Historic New England’s upcoming season, and can you share any broader designs for the organization beyond this year?

We have a new exhibition opening June 10 at the Eustis Estate in Milton, Mass., called “Loud, Naked & in Three Colors: The History of Tattooing in Boston.” As America’s industrial cities filled with factory workers eager for amusement, enterprising men and women discovered how they could make a living in the tattoo trade. This exhibition explores this phenomenon through a selection of flash art, photography and advertisements and tells the stories of the city’s leading tattoo pioneers.

We also recently launched ‘Recovering New England’s Voices,’ a multiyear, multiphase project to reimagine our sites by researching new and inclusive histories and sharing them through authentic, innovative storytelling. A key part of my job is to help expand and refine our collections, and we are working with local community leaders, artists, scholars and organizations from across the region to better represent the diversity of the New England experience. I am proud to be part of this exciting and important undertaking, one which will ultimately transform the way we understand and interpret our region’s history.

-Z.G. Burnett