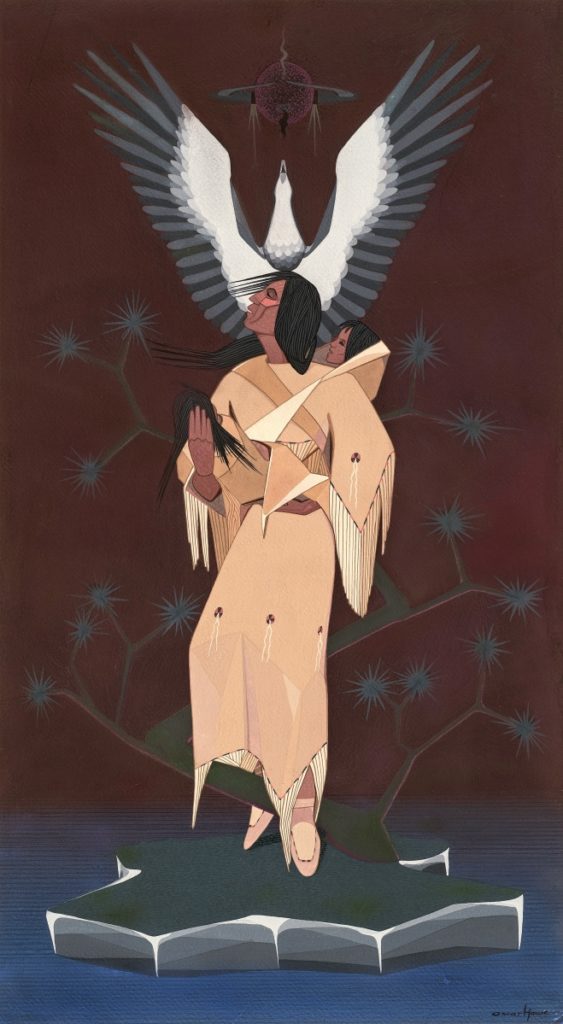

“Umine Dance” by Oscar Howe (Yanktonai Dakota, 1915-1983), 1958. Casein and gouache on paper, mounted to board, 18 by 22 inches. Garth Greenan Gallery, New York City.

By James D. Balestrieri

NEW YORK CITY – In his oft-cited essay, “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” poet T.S. Eliot wrote that “the difference between the present and the past is an awareness of the past in a way and to an extent which the past’s awareness of itself cannot show.” In this way, the artist has a responsibility not merely to understand the artistic and historical past but to absorb those parts of the past that are – or have become -inherent and alive in the present in order to build on and transcend them. For Eliot, personal expression was not enough. And yet, even when an artist understands and absorbs the past, transcending it does not automatically lead to acceptance. A certain level of translucence, where the tradition is recognized in the artwork, is required.

Native American modernism offers a case study. Ojibwe painter George Morrison (1919-2000), for example – whose works feature on a new series of United States Postal Service stamps – was an abstract expressionist who was often judged not “Indian enough” for juried exhibitions, even though his vibrant work has firm roots in Indigenous spirituality. Yanktonai Dakota artist Oscar Howe (1915-1983), the subject of a new exhibition, “Dakota Modern: The Art of Oscar Howe,” on view at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in New York City is another painter who was perceived in his lifetime as not authentically Native.

“Dakota Modern” is a crucial piece of the reappraisal of Indigenous modernism, a reappraisal compelled by the success of contemporary Native artists who are enjoying an explosion of invention and vision, embracing and enlarging on every imaginable style in their own traditions and in traditions far outside theirs, reshaping them to their own purposes and to tell their own stories. This ferment has naturally led to retrospections that explore the pioneers, the precursors, and the inspirations. Allan Houser and Fritz Scholder, of course, loom large here, but others, like Oscar Howe, were every bit as influential and are overdue to get their due, not only within the history of Native American art, but in the larger context of American modernism as well.

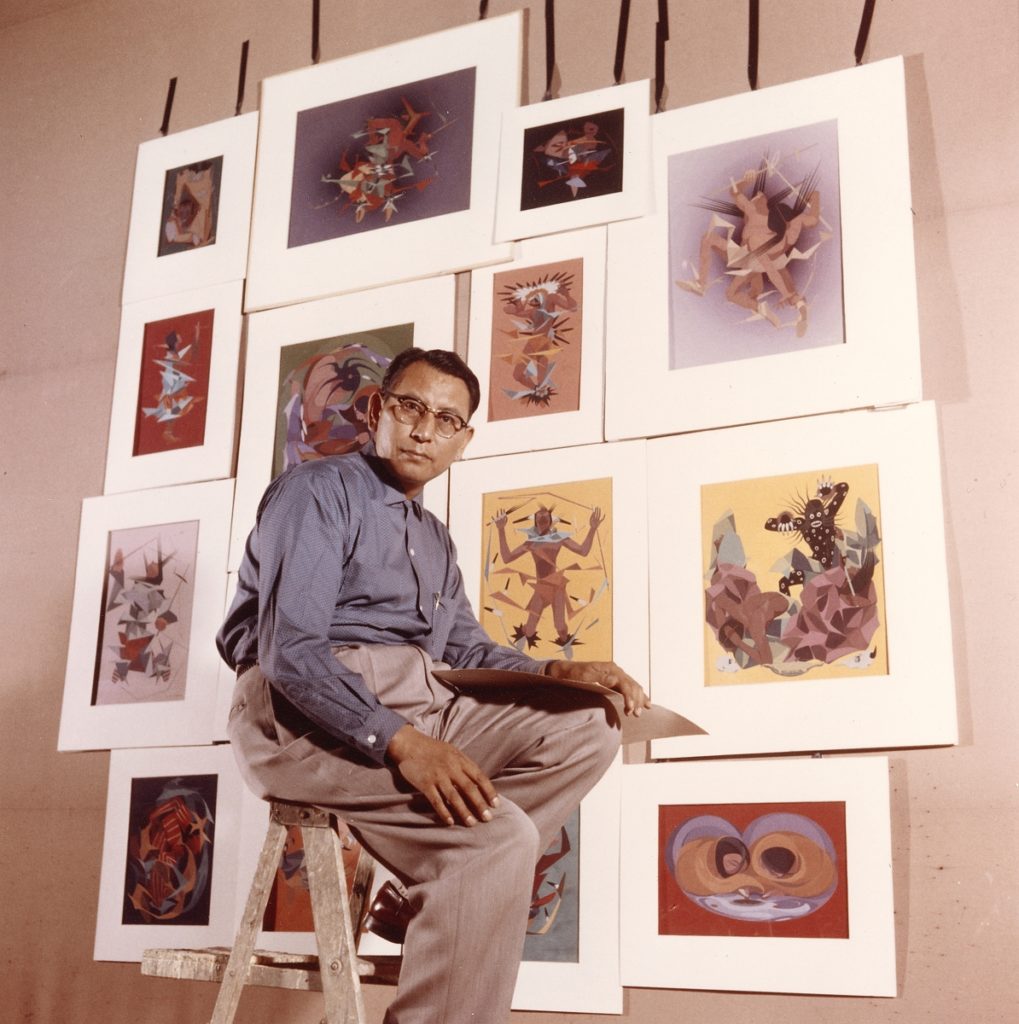

Oscar Howe, seated in front of a selection of his paintings at South Dakota State University, March 30, 1958. Oscar Howe papers, Richardson Collection, Archives and Special Collections, University Libraries, University of South Dakota.

Howe was born and would spend most of his life in his native South Dakota. In addition to his long career as an easel painter, he would become a respected teacher at the University of South Dakota and a prominent painter of murals. Between 1934-38, however, he studied at the Santa Fe Indian School under Dorothy Dunn. Works from this period, such as “Hunter’s Dream,” exemplify the Santa Fe, or Studio, style – Native motifs and symbols arranged geometrically against a neutral background, derived, in part, from pottery and other cultural objects. The Studio style would become a hallmark of the Indian Annual competition at Tulsa, Okla.’s Philbrook Art Center, where Howe would win awards, serve as juror and write a famous, fiery letter after his painting “Umine Wacipi (War and Peace Dance)” was disqualified from competition in 1958 as not conforming to rules such as this one: “The use of symbols that are not used by the artist’s own tribe, or related to the subject matter of a given painting is deplored. In future, it is hoped that purely decorative elements that serve only to fill up space will be kept to a minimum, if not altogether excluded. The jury feels strongly that the use of pseudo-symbols detracts, rather than adds, in any painting.” (Cat., p. 128) The exhibition and catalog note, and it should be repeated, that Philbrook employees did not serve as judges and that Native artists who had won prizes in the past served on the juries. Howe’s response, that Native artists were not to be dictated to like children and told what was and wasn’t Native art by Whites, was indignant. Howe wrote, “Indian Art can compete with any Art in the world, but not as a suppressed Art.” (Cat., p.126, Howe’s underlining). This letter paved the way for new categories in sculpture and “non-traditional” art in the 1959 Annual, categories that would be flooded with entries, providing one of the first serious outlets for Indigenous modernism.

Howe’s biography embodies contradictions, as an excellent – and corrective – essay in the catalog attests. As a result of a childhood illness, he spent many hours with his grandmother, who steeped him in the stories of their people, stories that would become the basis for Howe’s art. Yet he himself was a devout Episcopalian. Howe wanted his art to represent his people at their best, yet, as an academic – who married a woman from Germany – he found himself estranged from the reservation, and from his own family. Howe vehemently rejected scholarly comparisons between his work and that of the cubists, yet his master’s thesis, completed at the University of Oklahoma, as well as the accompanying artworks, demonstrate that he was not only exposed to but energized by modernist practice there, and that it would inform his work throughout his career. In short, Oscar Howe was a man on a tightrope, trying to make his own way and craft his own identity – as an artist and as human being – in an America whose attitudes towards Indigenous Peoples oscillated between patronization and hostility.

“Dakota Duck Hunt” by Oscar Howe (Yanktonai Dakota, 1915-1983), circa 1945. Watercolor on paper, 15-15/16 by 25-3/8 inches. Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, Okla.

Howe also never saw himself as an artist of social protest. Indeed, he actively avoided socially conscious subject matter – except in the harrowing, 1959-60 rendering of the “Wounded Knee Massacre,” with its echoes of Goya and Orozco – preferring to depict the rituals and ceremonies of the Ochéthi Šakówin peoples (the Santee, Yankton and Lakota of the Dakotas, Minnesota, and Wisconsin) to show that their spirituality was not part of the past or a mere atavism, but that it was alive, inherent and eternal, even under the terrible privations of reservation life.

Writing about his own process in 1979, Howe said, “I work the negative areas [and] non-objective design and then I allow lines to bring out the positive areas. In other words, the negative lines presented [sic] or suggest the positive part. It is my belief that the negative areas or background areas or patterns should be as beautiful if not more beautiful than the positive or foreground areas or patterns.” (Cat., p. 20)

Negative and positive. Non-objective and narrative. Abstract and realistic. In Dakota tradition, narrative art is the province of Dakota men. Keepers of history, their paintings on hide and ledger drawings record important events – battles, storms, harvests. On the other hand, abstractions and geometrical motifs are found in utilitarian arts – clothing, beadwork, jewelry, quillwork – that are the province of women. Howe’s combination of male and female recalls the wínkta, males among the Dakota who “live in the female realm” and wield great power “to protect and sustain community and cosmos.” (Cat., p. 16)

Dome of the Carnegie Resource Center, Mitchell, S.D., showing “Sun and Rain Clouds over Hills,” 1941. Mitchell Area Chamber of Commerce.

That Howe felt that the patterns in the background “should be as beautiful if not more beautiful” than the narrative elements suggests that story and rhythm were equally important to him and that they were inseparable and equally charged with meaning. In his catalog essay, “The Storyteller,” John P. Lukavic confirms this, inferring that Howe’s goal as an artist was, simultaneously, to preserve Ochéthi Šakówin culture for “cultural insiders” while finding ways to present it to the larger world. Lukavic writes: “Howe argued that, for Dakota people, ‘there was no abstract art because everyone grew up learning all symbols and meanings of all forms of art. They knew the main purpose of art for it was part of their daily life. The ancient Dakota belief in no abstract art is true today. Art is purposeful and esthetic.'” (Cat., p. 55)

What Howe was after then was a balance between showing and telling, between conserving and revealing, between telling a familiar story to people who know it and telling an entirely new story to people who know nothing of it. Howe’s art then, must be seen as a lifelong endeavor to create a visual language that would achieve these aims, a language that is modernist, but that cannot be channeled into cubism or any of the other extant Euro-American-isms.

Even in a painting that seems entirely non-objective, like the 1973 work, “Abstraction After Wakapana,” close study resolves the shapes into rolling hills, pointed peaks and other landforms, as well as watercourses perceived from above, the outlines of birds, tongues and peeks at the night sky through eyes, or reflected in them. Having just studied and written about M.C. Escher in these pages, “Abstraction After Wakapana” seems like a variation on Escher’s interlaced, regular natural forms distorted in a funhouse mirror – perhaps by time and memory – yet enduring nonetheless. Step back from the painting, however, and you may also see a marbled endpaper on the inside of an old, leather-bound book – the book of nature, perhaps, open to all who would read it and know its beauty and bounty.

“Origin of the Sioux” by Oscar Howe (Yanktonai Dakota, 1915-1983), circa 1955. Casein on paper, 25½ by 14 inches. Cutler Family Collection.

Oscar Howe’s art and story reminded me of another story.

When I was in graduate school, Seamus Heaney came to lecture on “Sounding Lines: Reflections on the Aural Element in Poetry.” We graduate students were treated to a private conversation with the poet. The exchange was brief and academic. I found myself alone with him. I had just returned from a year abroad, teaching in Wales for the most part, but for five weeks I had been in Heaney’s Northern Ireland, visiting distant relatives. I had walked Belfast and Portadown, where beautiful women in gallows glamour were dressed to be killed. I had been searched and questioned at British Army checkpoints – there were no tourists in Northern Ireland in 1986. My own cousins had accused me of spying for the IRA, based on my Italian surname and my refusal to bring anti-Catholic propaganda back to the States. I had taken a bus to Belfast to see Strauss’s Ariadne Aux Naxos at the newly reopened Belfast Opera House. I bought two tickets, but no one would go with me for fear of Nationalist IRA or Protestant UVF reprisals. I went alone and ate at the Crown, perhaps the most beautiful pub on the planet – once it had been rebuilt after the bombing.

I was young and angry. Heaney’s beautiful poems seemed apolitical and out of touch. I confronted him. For the next hour, the Nobel laureate spoke to me, and me alone, about cultural resistance and continuity, about art as politics with a small “p” enduring in the face of the violence of the moment, about art waiting patiently for dust to settle and blood to stanch.

“Dance of the Heyoka” by Oscar Howe (Yanktonai Dakota, 1915-1983), 1954. Casein on paper, 20¼ by 26¼ inches. Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, Okla. Museum purchase, 1954.

Elsewhere in “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” T.S. Eliot writes that the artist engages in a “continual surrender of himself as he is at the moment to something which is more valuable.” Cultural continuity and the surrender of the self to something “more valuable.” To be of one’s time and of one’s past – when these are worlds apart – and to attempt to reconcile these in art – invites rejection and misunderstanding. Yet this seems to me to lie at the heart of Oscar Howe’s art, where individual expression and the subsumption of the self into the greater culture turn out to be one and the same. These notions echo through the powerful paintings Oscar Howe created with the personal visual language he invented out of his own heritage and experience.

“Dakota Modern: The Art of Oscar Howe” will be on view at the National Museum of the American Indian until September 11.

The National Museum of the American Indian is at One Bowling Green. For information, www.americanindian.si.edu.