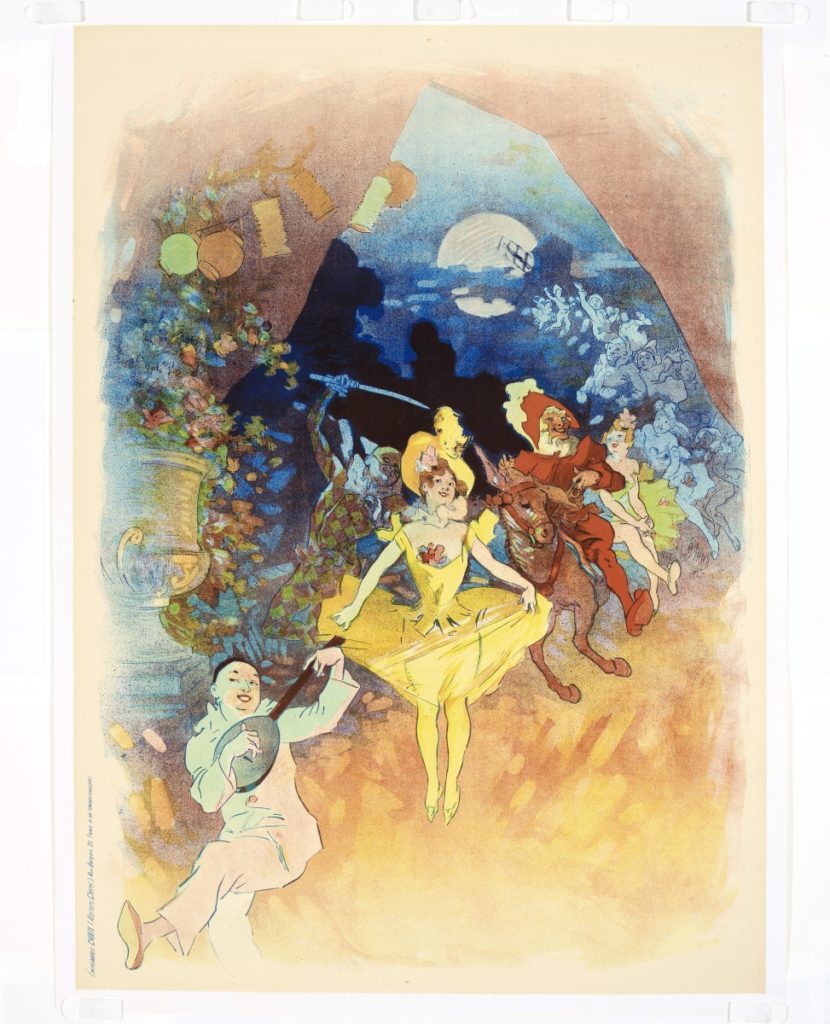

“Musée Grévin” [before letters] by Jules Chéret, 1900, color lithograph, 46½ by 32¾ inches (image); 48-3/8 by 34½ inches (sheet). The James and Susee Wiechmann Collection, M2021.372. —John R. Glembin photo

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

MILWAUKEE, WIS. – The Milwaukee Art Museum’s new exhibition opens with a 12-foot-high photo mural of a fin de siècle street corner in Paris, nearly every vertical surface covered with posters advertising liqueurs, entertainments, automobiles, and anything else a turn-of-the-century Parisian might want. The photograph replicates, to some extent, the overwhelming and immersive impact that these posters had on the urban landscape – and on the minds and pocketbooks of consumers. From the beginning, they were considered works of art as much as advertisements, and although the names of poster artists like Alphonse Mucha and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec are perhaps better remembered today, the true innovator of the genre was Jules Chéret (1836-1932).

Curator Nikki Otten explains that Chéret came up with a new way to make large-scale color posters with lithography in the late 1860s. Usually, lithographs – which are prints made from inked and greased drawings on a stone surface – require a different stone for each color, which is especially onerous when the stones were large. Chéret’s innovation was to figure out how to create large prints from only three stones: one inked in red, one in black and one shaded from orange-red to blue-green. Chéret’s first prints completed with this method were sensations, igniting a still-nascent collectors’ market for advertising prints. By 1877, he ran a large workshop supplied with steam-powered lithography presses, which allowed him to meet the high demand for his posters among both collectors and businesses who wanted to advertise their goods.

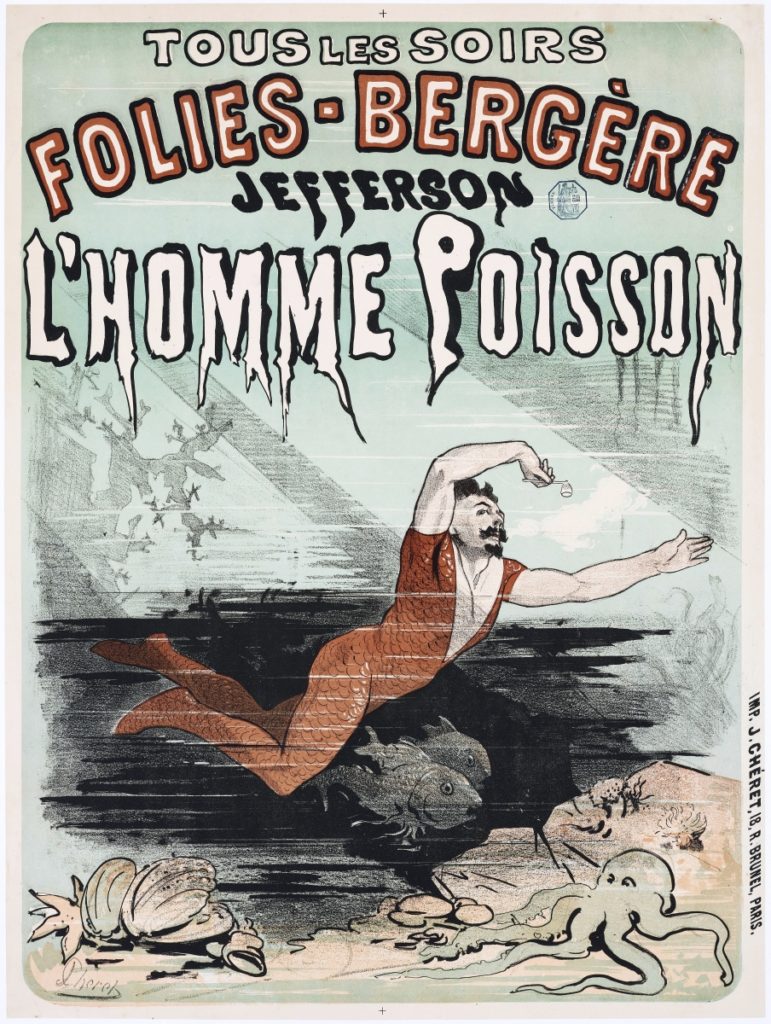

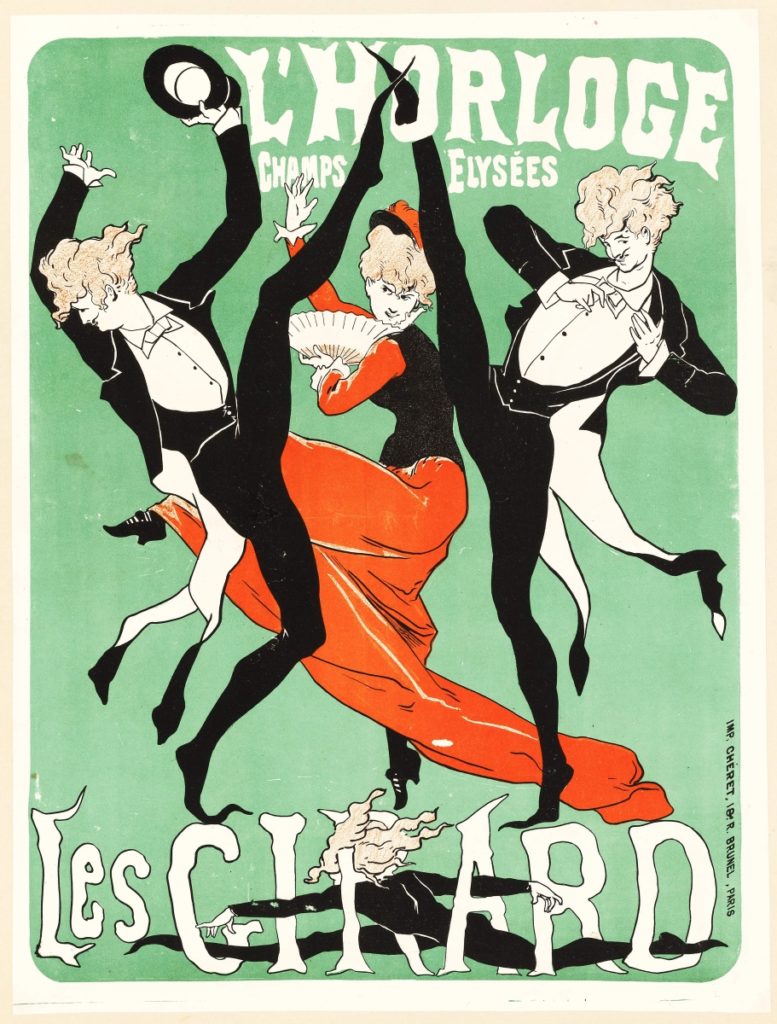

Two posters from this era – “Folies Bergère: Jefferson l’Homme Poisson” and “L’Horloge: Les Girard” – demonstrate the distinct palette and the gradient effects Chéret was able to achieve. In the former, Jefferson the “fish man” glides blithely through his aquatic tank installed at the famed Folies Bergère nightclub, with the bright orange of his classic Aquaman-like suit and the green of the water echoed in the paler tones of the rocks and sea life in the foreground. (Otten is particularly fond of this print and has gleaned some enthralling facts about the fish man, including that he later performed with two “fish women” named the Washingtons.) The palette is much the same in the latter print – in which the Girards are the performers and L’Horloge (The Clock) is the name of the venue – with the dancers’ peachy coiffures set against a teal background that in turn highlights the central figure’s vibrant orange-red dress.

“Saxoléine” by Jules Chéret, 1893, color lithograph, 91½ by 32 inches (image); 96½ by 34-5/16 inches (sheet). The James and Susee Wiechmann Collection, M2021.425.

—John R. Glembin photo

That animated personage might be seen as a precursor to another one of Chéret’s distinctive contributions to poster art: the female figure that came to be known, in his honor, as the chérette (explored in an excellent essay by Ruth E. Iskin in the exhibition catalog). Young, shapely, bursting with energy and barely clothed, these fantastical women bear some visual similarities to the performers in Paris’s many nightclubs and café-concerts – and Chéret painted them, too, including not only the female Girard but also performers at the Folies Bergère, Moulin Rouge and Musée Grévin (the wax museum, also a performance venue). But the true chérette had no real-world analogue and existed purely and exclusively to hawk consumer products like cigarette papers (“Job”), liqueurs (“Quinquina Dubonnet”) or the services of a print shop itself (“Bonnard Bidault: Affichage et distribution d’imprimes”). Witness, for example, the sprightly young woman balletically pouring herself a glass of “fortified” wine (fortified with cocaine, Otten clarifies) in “Vin Mariani,” clad in a nearly transparent yellow frock blown upward to reveal her bare thighs.

“Critics were very taken with the chérette, and there are all these over-the-top poems and articles dedicated to the chérette and how beautiful and wonderful she is,” says Otten, pointing out that she was primarily directed at male consumers. When the targeted buyer was more likely to be female than male, Chéret tended to lean on the more typical, already established type of the “Parisienne,” a respectable woman whose appearance and behavior was circumscribed by the limitations and expectations of what was appropriate for women’s participation in public urban life. Chéret’s department store advertisements, like “Halle aux Chapeaux,” employ this type “to serve as a role model for these women,” Otten says. “They could see themselves as this person, wearing those clothes, shopping at the same stores.” These posters also often featured children, stressing the domestic sphere not only as a cultural ideal but a ripe market for consumer goods like clothes and toys.

“Folies-Bergère: Jefferson l’Homme Poisson” by Jules Chéret, 1876, color lithograph, 29¾ by 21-7/8 inches (image); 30¾ by 23 inches (sheet). The James and Susee Wiechmann Collection, M2021.144. —John R. Glembin photo

Chéret’s posters ultimately became consumer products in and of themselves, essentially creating a brand new market for poster collecting in Nineteenth Century Paris. “The first people who collected Chéret’s posters needed to follow “bill stickers” around and bribe them to get one of the posters before they were pasted to the wall,” Otten notes, “or some people would wait until it rained and the wheat paste got wet, and they would peel posters off the walls themselves.” But increased critical attention led to a legitimate collector’s market, and Chéret began to edition versions of his images without the advertising copy on them, selling them directly to connoisseurs and collectors. The fact that they were initially conceived as advertisements was no deterrent; it was even an attraction for some. Otten observes that the way the posters recorded contemporary life in all its ephemerality – the products that were being advertised often lasted not much longer than the posters themselves – was part of their appeal. “There’s commerce tied up in there, there’s fine art… and also historical information all wrapped up together, so it’s a really interesting moment when people are starting to recognize these advertisements as something more significant than simply selling you something.”

That idea of ephemerality, of popular art that “wasn’t necessarily supposed to survive after a couple of days,” is something Otten has tried to suggest in the installation at Milwaukee. It wasn’t feasible to wheat-paste the posters to the gallery walls – removing them would have risked damage – but they are framed simply and hung in tight groupings to suggest the “museum of the streets” that Nineteenth Century Parisians would have experienced. There has also been an effort to bring the exhibition outside of the museum’s four walls with a new poster, commissioned for the exhibition, by artist Ericka Walker. “That one we were able to wheat-paste directly onto the wall [in the introductory section of the exhibition], so people will see what that would have looked like,” says Otten. There are also plans to hang some of the 300 impressions of Walker’s print in locations throughout Milwaukee, “so that people will be able to happen upon a work of art in the way that they would have in Chéret’s time.” True to Chéret’s own modus operandi, a limited edition of the poster, sans advertising copy, is available for purchase in the museum shop.

As Chéret’s style matured, and as the capabilities of his workshop continued to grow, he created ever-more sophisticated compositions for increasingly upper-crust products and consumers. The very first Chéret poster to catch the eyes of James and Susee Wiechmann – the couple who assembled the collection of some 600 Chéret prints that came to the Milwaukee art Museum in 2021 – was “Cosmydor Savon,” a soap advertisement featuring a statuesque woman in a striped gown who is not exactly a chérette but not a bourgeois housewife, either. Something similar can be seen in “Palais de Glace,” advertising an ice-skating rink – the skater is more put together than the manic pixie dream girls selling liqueurs and wines, but her coquettish pose and expression (and the gaze of the man behind her) suggest that she is very much designed to appeal to a male clientele. A series of works advertising Saxoléine lamp oil – Chéret created nine different designs, Otten says, between 1891 and 1900 – feature comparably idealized female figures, all “beautifully clothed… reaching for lamps and turning up the light and illuminating themselves.”

“L’Horloge: Les Girard” by Jules Chéret, 1875/1878 or 1880/1881, color lithograph, 22½ by 17 inches. The James and Susee Wiechmann Collection, M2021.259.

—John R. Glembin photo

In addition to the delights of departments stores, entertainments and various consumables – from soaps to aperitifs – the works on view also feature travel posters, mostly for seaside towns accessible by the ever-expanding French rail lines, and promotions for newspapers. “My favorite one is for ‘L’Echo de Paris,'” says Otten. “It’s a female figure who is kind of floating in the air, and she is wearing a cap folded out of the newspapers that she is selling, and she’s also wearing a dress made out of those newspapers.” Newspapers also ran serialized novels at this time, to compete with other publishers for subscribers and new readers, and several posters on view advertise those works in all their sensationalistic glory: “there are a lot of affairs and assumed identities and shipwrecks and children out of wedlock.”

Chéret’s wild popularity in his day, and his role in pioneering this distinct art form – fully recognized during his lifetime with the award of the Légion d’honneur in 1890 – begs the question of why this should be the first-ever exhibition dedicated to his work in the United States. Otten speculates that it could be partly because the cheerful effervescence of his work fell out of favor in the war-riven Twentieth Century, when the darker aesthetic of poster artists like Toulouse-Lautrec entered the art-historical canon instead. It could also be that Chéret himself never cultivated the tortured-genius persona that Toulouse-Lautrec and others embodied. “In the photo that I use of him often in presentations,” says Otten, “he is in his studio, and he has a fencing épée and gloves and he has a pastel or a painting in front of him and posters on the walls. I think he’s trying to present himself as a very elevated and cultured person, which doesn’t always grab the same headlines.” It’s an ironic thing to happen an artist who so brilliantly deployed headlines and to grab attention for others – but luckily, the Weichmanns’ gift to Milwaukee, and the museum’s enthusiastic celebration of it in this exhibition, will redirect some of that attention back to its source.

“Always New: The Posters of Jules Chéret” is on view at the Milwaukee Art Museum through October 16.

The Milwaukee Art Museum is at 700 North Art Museum Drive. For information, 414-224-3200 or www.mam.org.