“The Ship Charles of London Whaling” by the Brittania Engraver, circa 1850s, whale tooth and pigment, 5¼ inches. Private Collection.

By Kristin Nord

COTUIT, MASS. – The Cahoon Museum of American Art is brilliantly adorned with scrimshaw from the Age of Whaling this summer in a glorious exhibition of more than 250 decorative and utilitarian works, “Scrimshaw: The Whaler’s Art,” that is on view through October 30.

For Dr Alan Granby, the renowned Hyannis Port, Mass., dealer of maritime antiques who has guest curated this marvelous show, it was an opportune time to draw upon some 40 years of his own research and experience and to secure loans from seven museums and 19 leading collectors. Working again with Dr Sarah Johnson, the Cahoon’s executive director, for this second maritime exhibition in four years has been a collaborative delight, he said recently, enabling him to bring together top quality works he’s shepherded over the years to good homes. For Johnson as well, it’s been a time to celebrate the museum’s history, which includes a painting by Ralph Cahoon, who had a studio and gallery in what is now the museum – and whose Twentieth Century works often featured scrimshaw.

The exhibition is accompanied by Granby’s hot-off-the-press Wandering Whalemen and Their Art: A Collection of Scrimshaw Masterpieces, a gorgeous tome that captures these objects in life-size images. For scrimshaw lovers, the book provides a spectacular overview of the connections to historic life on Cape Cod, Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard and New Bedford, and demonstrates the ways in which whalers from diverse backgrounds made art during whaling’s golden age of sail.

Crimper with whale tale, whale bone and baleen. Private Collection, photo courtesy Jim Goodnough Photography.

Scrimshaw became the preferred pastime from approximately 1820 to 1860, when whaling was the mainstay of the New England and Eastern Long Island economy. Stuart M. Frank, PhD, a leading scrimshaw scholar who has overseen collections at Mystic Seaport Museum and the New Bedford Whaling Museum, has traced early scrimshaw to the 1760s, when a few Massachusetts whalers working independently carved a small handful of rudimentary pictures and crude inscriptions on skeletal whalebone. But it was after the Napoleonic wars, when whaling voyages on the open sea grew much longer (now venturing for a matter of years around Cape Horn and the Cape of Good Hope to the Pacific and Indian Oceans, the High Arctic and the threshold of Antarctica) that scrimshaw became a common occupational art, he writes, in the book’s foreword.

Whaling ships were being dispatched to sperm whale hunting grounds in pursuit of spermaceti oil, the clean-burning fuel in its raw state that could also be processed into candles. Spermaceti products formed the basis of the greatest fortunes accumulated in Nantucket and other New England whaling ports. It was also in the whale byproducts that the whalers experimented with what soon fed their favorite hobby. These materials could be carved in relief or fully in the round, to produce sculptural forms, human and animal figures, handles, tools and all manner of objects.

Whaling crews were an interracial mix: of Native Americans, some of whom hailed from whaling dynasties; African Americans, some of whom were former slaves; and immigrants from Britain, Ireland, Continental Europe and Portugal (the Azores Islands, in particular).

“Most recruits were young, some lured to sea by recruiters who spun tales of financial gain, adventure and exotic islands; while others looked for escape from creditors, jail or the drudgery of the farm,” Frank writes.

Tub, mid-Nineteenth Century, whale bone and baleen. Private Collection.

Life on board ship was a complex transaction that revolved around a recruit’s economic situation more than his race or ethnicity. On the one hand, Native Americans could rise through the ranks and be valued for their skills and expertise; on the other, as in the case of 17-year-old Aaron Keeter, a Mashpee Wampanoag, found themselves caught in the colonial system of credit, debt, labor contracts and indentured servitude. Those at the bottom were consigned to the worst vermin-ridden quarters, ate the most rancid food and often finished their contracts in debt to the ships’ captains.

Then there was the grim, bloody and dangerous work itself. The ship functioned as an abattoir, undertaken in feverish spurts in between extended months of tedium. During long periods of leisure time – whaling ships were on the open sea for generally 40 months at a time – the response to these adverse conditions was a rich culture of songs and stories and scrimshaw.

A scrimshander’s primary materials were whale byproducts: sperm whale ivory, walrus ivory, baleen and skeletal bone, often in combination with other “found” materials. The characteristic basic black pigment was lampblack, a suspension of carbon in oil, the product of combustion, easily obtained from the shipboard tryworks (oil cookery) or from oil lamps. Colored pigments for polychrome works were sometimes used as well, whether verdigris (a tenacious green deposit naturally forming on copper and brass) or generated from fruit and vegetable dyes or commercially produced colored inks.

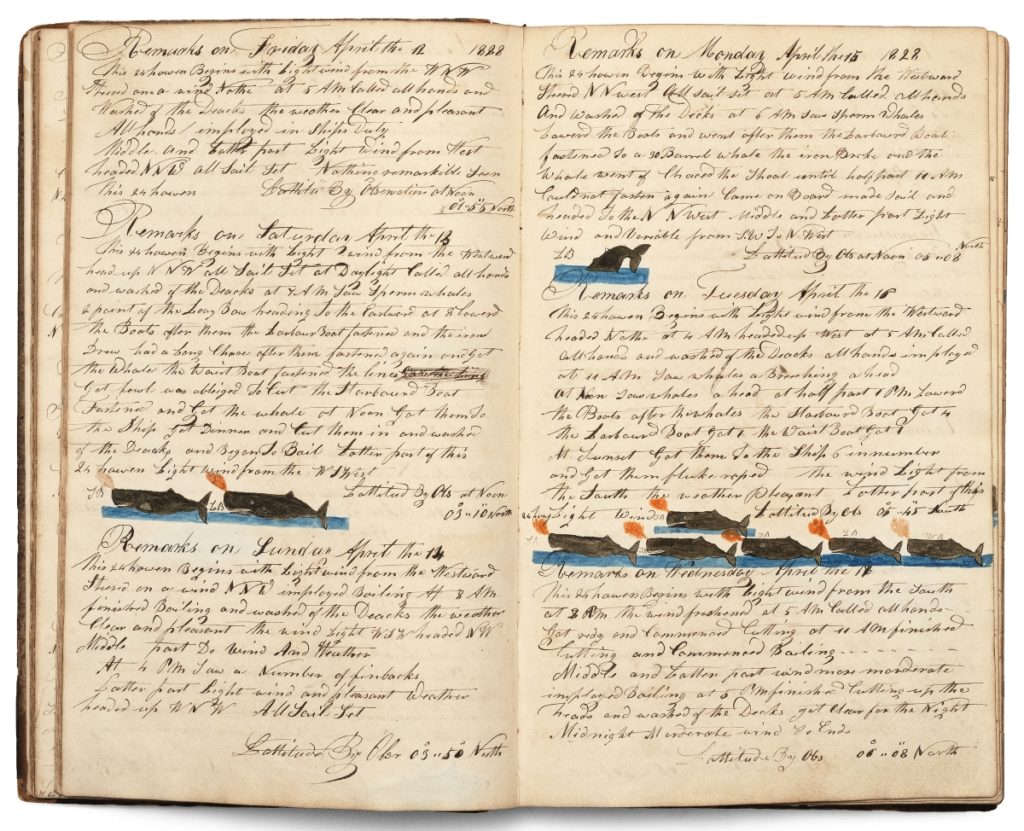

Journal of a Whaling Voyage of the Ship ‘Rodman,’ 1827-30. Private Collection.

“Many scrimshanders of the Nineteenth Century had training as craftsmen – carpenters, joiners, mechanics, blacksmiths, engravers,” Stanford A. Moss writes, in the 2021 Spring/Summer issue of Scrimshaw Observer. “They knew how to use taps and dies (and even how to make them); how to construct a wooden dovetail joint; and the difference between a mortise and a tenon. And if they went to sea without that sort of knowledge, they had every opportunity to learn it from their crewman peers as the ships slowly plodded around the world. While most pictorial engraved scrimshaw might come from an artistic tradition, the tools come from a woodworking tradition.”

As these men moved from idea to execution, they used those techniques to suit the project at hand. Generally, they used sharp, straight-bladed knives (marking knives) for etching and files, sharp pieces of broken glass and dried sharkskin to smooth the ivory and bone surfaces.

Once the surface was prepared, the scrimshander needed a firm hand and a solid perch from which to engrave an original image – or in most cases, an illustration pulled from a periodical, or a pattern book brought onboard.

As it turned out, the whaling communities of New Bedford and Nantucket, in particular, placed a high value on schooling, but even American farm boys and urban youths were reasonably literate, Frank said.

Those who kept journals – and there is a marvelous example in the exhibition – did so with care and artistry. They were not only diligent in their recordkeeping, but often added their own illustrative accounts of whale hunts and scenes of exotic locales.

Cane with handle in the form of a fist crushing a serpent, mid-Nineteenth Century, whale ivory, silver and tortoiseshell. Private Collection.

Asking Granby to select his favorite object in this exhibition is very much like asking a father to choose his favorite child. There are many showstoppers that will entice visitors to linger. Among these, the tooth the Nantucket scrimshander Edward Burdett (1805-1833) engraved on board the ship Japan of Nantucket Island during a voyage between 1825 and 1829. It is one of 17 known to have been carved by this whaler in his short life, with its tapered seas, deeply cut intaglio ship hulls, and leaf and berry or sawtooth floral borders. Then the works by the Britannia Engraver, and early scrimshanders Nathan Sylvester Finney (1813-1879), Frederick Myrick (1808-1862), Josiah Sheffield (1807-1880), and whalers aboard the ship, Ceres, William Gilpin (active 1830s-40s), Edmond M. Chandler Jr (1809-1857) and possibly William H. Meyers (each identified in shipboard journals). There are two magnificent teeth by the Albatross Artist (1830s-40s), featuring dramatic whaling scenes on one side and elegant Federal-style homes and gardens on the other.

This artform gave whalers a chance to demonstrate their carving skills, and sometimes their patriotic fervor. A work created by O. Lindboarms (1874), which chronicles the 1874 voyage of the Navy ship Swatara on its transport mission to sub-Antarctica to observe the transit of Venus, ranks among the finest of patriotic scrimshaw, Granby said.

At a time when women’s fashions dictated a 14-inch waist, women initially and essentially stuffed themselves into iron cages under their gowns. They later used baleen busks in their pursuit of an hourglass figure. When these rather draconian measures went out of style, the busks, often with masterful engraving and inlay work, became keepsakes.

Walking sticks were seen as a gentleman’s necessary accessory, and this gave scrimshanders another platform on which to display their carving virtuosity.

Ship hull trinket box by Manuel Silvia, circa 1860s, whale ivory and pigment. Collection of the Nantucket Historical Association.

Then there are the ditty boxes, swifts, hoops and clothespins, utilitarian tools, clocks, bird cages, tobacco pipes and reticulated baskets. And Johnson’s favorites – the pie crimpers. The adage of “American as apple pie” undoubtedly came from this period, when sweet and savory pies were daily staples. The carved crimpers on display are so fanciful and finely carved that it’s hard to imagine them ever pressed into service. More likely they wound up as art mounted on kitchen walls rather than relegated to worktables. There are graceful running dog crimpers, unicorn crimpers, serpent and therianthropic crimpers; scrimshanders really had fun with these.

“The men who set off on whaling voyages certainly did not do so with the intent of making art,” Frank writes. “They set off to make money, to wrestle and conquer a beast, to experience more than they ever had or would again.”

And yet, paradoxically, in this dangerous, grim, filthy and bloody setting, whalers developed an occupational art form that inspires and still dazzles. Scrimshaw truly was art for art’s sake,” Granby said, and it remains a testament to the human spirit.

The Cahoon Museum of American Art is at 4676 Falmouth Road (Route 28). For more information, www.cahoonmuseum.org or 508-428-7581.