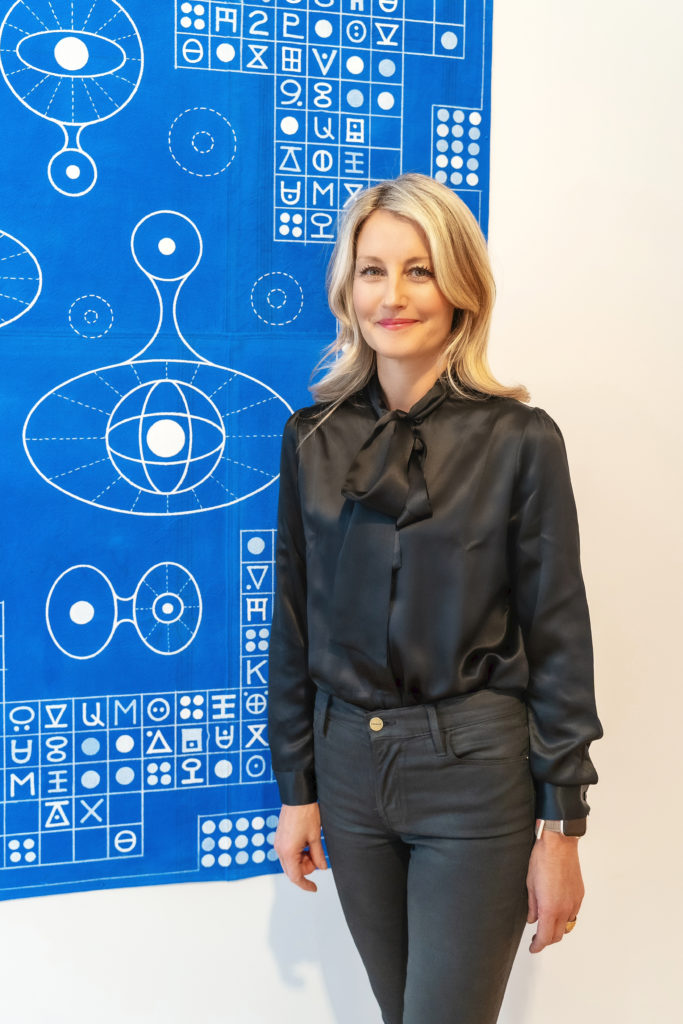

In June of this year, the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum announced that Amy Smith-Stewart had been named chief curator after nine years at the museum. She succeeds Richard Klein, who retired from his position as the Aldrich’s exhibitions director after more than 30 years at the museum. Having previously served as curator and senior curator, Smith-Stewart is the first woman to lead the Aldrich’s exhibitions department. We caught up with her to discuss the museum’s role in presenting visionary art and how she intends to help grow its exhibitions, projects and publications.

Congratulations on your new role! How does it feel to be the Aldrich’s first woman to lead its exhibitions department?

It’s a cliché to say but it is a dream to be at the curatorial helm of a museum with such a remarkable reputation for supporting artists. Intimately scaled museums, like the Aldrich, are great places to learn and grow as a curator, because they are nimble, collaborative, elastic and quick to respond and adapt to events happening in real time – these qualities also align with how artists make work in the studio.

In your previous nine years with the institution, what changes in its curatorial vision have you witnessed and supported?

When I first started at the museum, the exhibition schedule was biannual with themed semesters. During my tenure, we grew the schedule from two openings to three a year. We dropped the themes to spotlight the artists, tailoring the mission to first-time museum shows for emerging or early career artists, mid- and late-career surveys of underrepresented artists and thematic group exhibitions with topical themes. We also moved from making brochures to publishing catalogs and books for all our exhibitions; another critical way for institutions to show support of an artist’s career by creating or expanding discourse. Often, we are publishing an artist’s first museum publication. We also developed more consistent programming on the museum’s grounds – an area we will continue to grow as we revamp our outdoor campus over the next year or so. We launched two new series: Aldrich Projects, which introduces a singular work or focused body of work every four months, and the Aldrich Box, a traveling exhibition in a box that provides audience engagement beyond the museum’s walls. All of this was done to increase opportunities for artists and augment contemporary art engagement for our audiences. We are traveling our exhibitions more and will be collaborating with other institutions on co-authored shows. We are also launching a formal artist honoraria policy in 2023.

“52 Artists: A Feminist Milestone” (installation view, left, Kiyan Williams, “Sentient Ruin 7,” 2022, courtesy the artist and Lyles & King, New York; right, LJ Roberts, “Anywhere, Everywhere,” 2022, courtesy of the artist and Hales, London and New York; outdoors, Alice Aycock, untitled (Cyclone), 2017, courtesy of the artist and Marlborough Gallery, New York, the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, June 6, 2022 to January 8, 2023. Photo: Jason Mandella

Since one of the stated missions of the museum is to uncover and amplify new and unrecognized artists, what have been some of the important solo museum firsts?

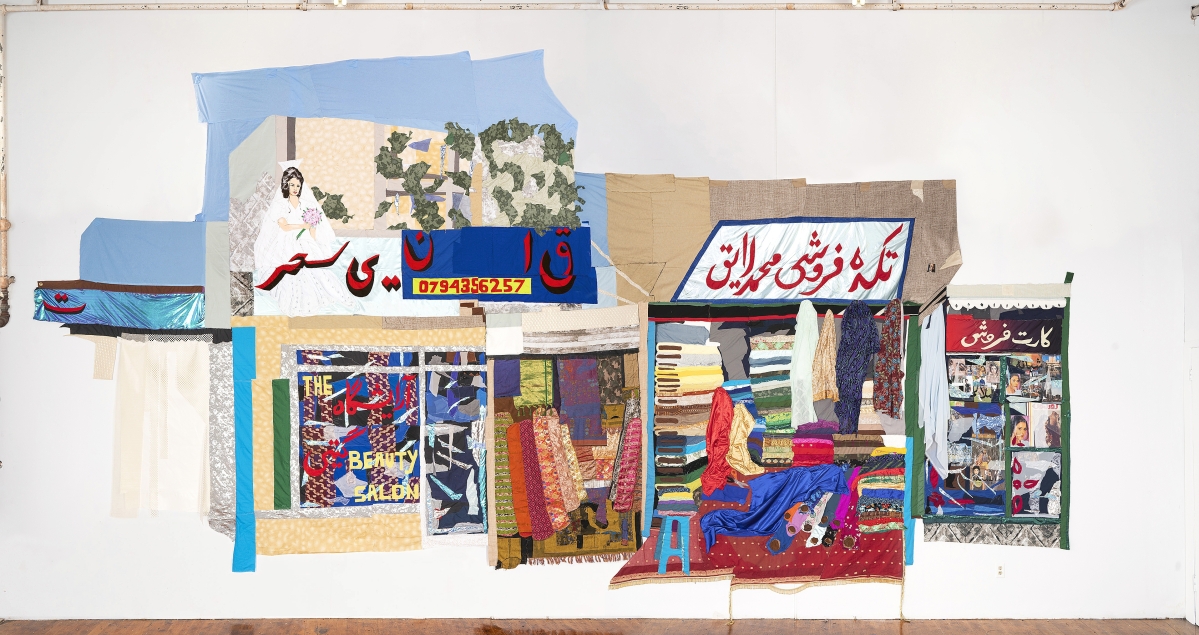

During my time at the museum some meaningful personal “firsts” are Harmony Hammond’s first museum survey, spanning 50 years, “Material Witness,” and Karla Knight’s 35-year first survey, “Navigator.” For both artists, we published their first hardcover monographs. I’m also very excited about what’s ahead: the first-time solo museum shows for Afghan Canadian New Haven-based artist Hangama Amiri and LA-based artist Chiffon Thomas (who will also be creating their first outdoor work on Main Street); and a major traveling museum exhibition with Raven Halfmoon, a collaboration with chief curator and director of public programs Rachel Adams at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts.

Describe your own personal process of partnering with an artist to shape an exhibition.

I work intuitively and collaboratively with artists. When I work with an artist(s) on an exhibition – solo or group/themed – it starts with an open and active dialogue. For solo shows, we work together to determine what would be most meaningful for their practice: should we support the production of new work and/or borrow work for context, highlight a never-before-seen aspect of their practice or is there interest to push the work into new territory, for instance, by making outdoor work, commissioning work or supporting the creation of something site-specific or inspired by the context around the museum, or perhaps even partnering with our community, etc. For group shows, it is not about finding a work that fits nicely into a preconceived concept. The context must also amplify ideas circulating within the work itself. My process is not curator-determined but artist-driven, what best serves their work while also adhering to the museum’s mission. If I follow this strategy, then I feel confident that audiences will feel this when they see the show.

What are some of the board’s primary expectations for the museum going forward?

I don’t want to speak on behalf of the board but I believe that my job is to steer a department towards a program that is diverse, inclusive, mission-driven, artist-centric and collaborative, supporting and nurturing artists and inspiring audiences while also growing our communities close by and around the world.

Hangama Amiri, “Bazaar, A Recollection of Home” (installation view), T293 Gallery, Rome, Italy, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

The Aldrich is not without some controversy vis-à-vis the local community. I am thinking of the “Big Baby” in 2004, a 12-foot-high baby mounted in front of the museum, for which your predecessor had to field all sorts of public reactions, many of them negative. How do you engage a local audience for art that is not in the mainstream?

I have always looked to contemporary art to expand my world view by asking questions rather than giving out answers. The Aldrich is one of few museums located in a US suburb. Our role as curators is to make contemporary art accessible to everyone by providing a diverse, equitable, accessible and inclusive experience. We do this by providing meaningful connections to works on view that expand our global view. We have many visitors from our local communities that see contemporary art first at the Aldrich. This is what makes working here so exciting. Contemporary art reflects what’s happening on our planet right now. Sometimes there are perspectives or ideas active in artworks that are not always in alignment with our personal experiences or might not be what some audiences want to see or learn about at a particular moment, but it is critical that platforms for artists of diverse perspectives and vantage points exist and that it is presented in thoughtful and accessible ways. Throughout art history, there have been countless instances of now canonical works of art and artists exiled or censored by institutions. There are also scores of artists and artworks that have been expunged or excluded from the history of art, and our job as curators is to change and add to visual culture, advocating for social justice and a healthy planet, countering what has historically been white, male and Western-centric.

What plans does the museum have for updating the museum’s campus, which comprises not only the main building but also the Sculpture Garden and “Old Hundred,” the historic New England colonial with a restored front porch?

We have learned through the pandemic how much our audiences love seeing artwork in plein air. Public art spaces are free and accessible daily from dawn until dusk. Without going into a whole lot of detail, we are planning to make the grounds more available for all audiences by putting in pathways, lighting and seating and creating intimate as well as collective experiences to see art within nature. We will also create better sightlines for placing art and more open-air interdisciplinary public programming. So, the Aldrich’s outdoor spaces will be a site for connection, creation and sustainable wellbeing.

Harmony Hammond, “Material Witness: Five Decades of Art,” The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, March 3 to September 15, 2019 (installation view, left clockwise, “Floorpiece V”; “IV”; “II”; “III”; “VI,” all 1973). Courtesy of the artist and Alexander Gray Associates, New York ©2018 Harmony Hammond / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photo: Jason Mandella

Which among the more than 40 exhibitions and projects you’ve shepherded at the museum was the most challenging?

Every exhibition has its challenges, but “52 Artists: A Feminist Milestone” was the most challenging and rewarding of my career for so many reasons. First, it’s coordination was the synthesis of two curatorial directives in one: the recreation of a historical landmark exhibition from 1971 by one of the most important activist curators of recent history, Lucy Lippard and the creation of a new list of artists to track feminist art practice over a half century later in 2022; this entailed researching and locating artists from the 1971 exhibition; the recreation of historical works 50 years later; the creation of new works by the younger generation; installing a cohesive installation, encompassing the entirety of the museum’s building and grounds (the first time a single show has taken over the museum’s new building since it was inaugurated in 2004); and publishing a major book to synthesize all this material and add to an ongoing feminist art history.

What were your selection criteria for the show?

Our criteria for the new list was to invite 26 emerging female identifying and nonbinary artists based in New York City, born in or after 1980, who had not had a solo museum exhibition in the United States as of March 1, 2022.

Best restaurant in Ridgefield to repair to after having viewed an Aldrich exhibition?

Luc’s, hands down!

-W.A. Demers