“Le petit prince survolant une planète avec montagnes et fleuve (The little prince flying over a planet with mountains and river)” by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, New York, 1942, watercolor and ink on onionskin paper, overall: 10-7/8 by 8-3/8 inches. Purchased on the Elisabeth Ball Fund, 1968.

By James D. Balestrieri

NEW YORK CITY – Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince begins with his drawing of a boa constrictor swallowing an animal. “Here is a copy of the drawing,” he writes, in present tense, as if he has just drawn the picture – of a toothed boa and a terrified, half-swallowed animal – for us. But, as he says, it is a copy, drawn from a childhood memory of an illustration in a book. And it’s childhood that brings The Little Prince to life. The slender, much-beloved book is addressed to children – and the children who reside in all of us. Having seen the illustration, young Antoine drew the next scene – an elephant inside a boa constrictor. To grownups, the drawing looked like a hat and, as Saint-Exupéry writes, “at the age of six, I gave up what might have been a magnificent career as a painter.” This, he goes on, is due to the fact that, “Grown-ups never understand anything by themselves, and it is tiresome for children to be always and forever explaining things to them.” Soon, the narrator lets us know that he is a pilot, lost in the desert and desperate to repair the broken engine in his plane – the pilot who meets a little prince who has journeyed from his little planet. The little prince asks him to draw a sheep. But the pilot draws the elephant inside the boa constrictor, the “hat” all the grownups had seen. The little prince, being a child, sees this right away, exclaiming, “No, no, no! I don’t want an elephant inside a boa constrictor.” The connection closes a loop and gives the pilot, a grownup, a path back to childhood. This path to childhood is one he will need to take in order to understand the story that the little prince tells and, importantly, in order to convey the story to the reader.

The Morgan Library & Museum holds the original manuscript and art for The Little Prince. The museum’s new exhibition, “The Little Prince: Taking Flight,” on view through January 15, presents Saint-Exupéry’s watercolors, drawings and manuscript drafts, showcasing the writer and artist’s creative process as this classic work took shape.

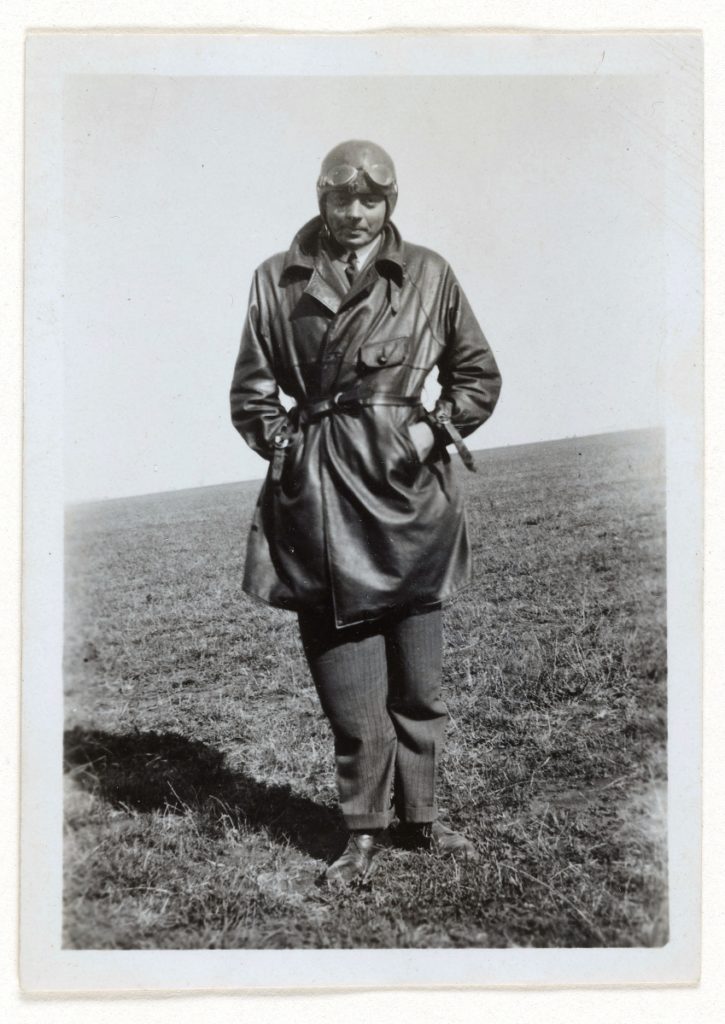

The context of the creation of The Little Prince is crucial. An impoverished noble by birth, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (1900-1944) joined the French military to help support his family, began taking flying lessons and soon began to make his name as a celebrated aviator in North Africa and Argentina, helping to establish often-perilous air mail routes. At the same time, Saint-Exupéry began to find literary fame with lyrical, philosophical works about the joys of flying and the solitude of the skies over deserts and mountains.

“Le petit prince et la main du pilote tenant un Marteau (The little prince and the pilot’s hand holding a hammer)” by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, New York, 1942, watercolor and ink on onionskin paper, overall: 5½ by 8-7/16 inches. Purchased on the Elisabeth Ball Fund, 1968.

In January 1941, after the fall of France, Saint-Exupéry lived in exile in the New York City area and elsewhere in the United States and Canada. In other words, he wrote and illustrated The Little Prince during a time of great sorrow for his country, a time when he was also drumming up support in the United States for the war effort. Two years later, in April of 1943, the year The Little Prince was first printed, Saint-Exupéry shipped out with an American convoy, joining the Free French Air Force in Algiers where he would get back into the fray against the Axis. On July 31, 1944, he made his final flight, disappearing over the Mediterranean. In 2000, a fisherman found an identity bracelet on an island south of Marseille, bearing his name; in that same year, wreckage from his P-38 Lightning fighter plane was also discovered.

The romance between the French and the North African desert, where France ruled as a colonial power, is the stuff of novels, films and all the arts -the Foreign Legion, Beau Geste, Gary Cooper and Marlene Dietrich in Sahara, the casbah, Casablanca. Scholar Edward Said famously coined this lure of the desert and the fetishism of the other, “Orientalism.” In Saint-Exupéry’s case, however, flight seems to have stripped away even the exoticism. The titles of his other books tell a tale: Southern Mail; Night Flight; Wind, Sand, and Stars; and Flight to Arras. And as he flew his night flights over mountain and desert, gravity let the trappings of society fall away, leaving a poetry of solitude that might almost be called Buddhist if it weren’t so childlike in its wonder. It’s interesting to compare Saint-Exupéry with his Existentialist contemporaries: Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Eugène Ionesco, Jean Anouilh. You find the same lyrical critique of self-absorbed, bourgeois culture in Saint-Exupéry as in his contemporaries. What you don’t find is the dark absurdity and cynicism. I wonder how Camus et al might have been different if they had learned to pilot a plane. Indeed, the French man of letters who comes closest to Saint-Exupéry might be the novelist and art historian André Malraux, who was a pilot and soldier, and whose works always seem to harbor some measure of hope, hope that he finds in the plenitude of world cultures and in their survival against often terrible odds.

To an American in the 1930s- 40s, there must have been something almost stereotypical about Saint-Exupéry, as if he were a character who stepped out of an Ernest Hemingway novel – For Whom the Bell Tolls immediately springs to mind. Saint-Exupéry is the last romantic, a loner who was never more at home than when he was flying over the desert at night, fated to die for France in a war already lost. He even flew his last sorties out of Tangiers and Casablanca. His relationship with his wife was tempestuous. There were affairs, recriminations, reconciliations, all of which folds into the inspiration for the little prince’s rose, a flower he realizes is unique when he sees a garden full of roses on Earth.

“Portrait of Saint-Exupéry in pilot outfit, Buenos Aires,” 1930. Purchased on the Drue Heinz Twentieth Century Literature Fund, 2021.

It is the little prince’s meeting with the fox that opens his eyes, and it is the retelling of this meeting by the little prince that opens the pilot’s eyes. What does the fox say? “It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.” But grownups don’t see this, and, at first, the pilot doesn’t. Further, and this seems to be something the pilot can understand: If love tames you – that is, if love binds you to someone, whether they are tamed by you, or not – you run the risk of loss, and of the pain that comes from loss. This love, the fox and the little prince suggest, can be for anyone or anything. A person, family, country, place, even one’s own native culture and art, all of which are encapsulated in the rose that the little prince loves, left when she (the rose) broke his heart, and – we hope but do not know – returns to.

I had never read The Little Prince before. At least, not in English. I remember fighting through it as the first real story we assayed in high school French class. This time, for this story, as I read it, I was struck by its simplicity and readily understood its enduring appeal to children. The story offers gentle avenues to the world of adults that children witness but do not fully comprehend, a world filled with selfishness, materialism, narcissism, futility, greed, love, loss, haste, death, and rules and laws without meaning. Only love and wonder, which are invisible, are worthwhile. I also took the opportunity to reread the other book Saint-Exupéry wrote during his American exile, Flight to Arras, which chronicles his time and thoughts as a reconnaissance pilot during the last days before the fall of France.

In The Little Prince, the grownup pilot has to shed his adult perspective in order to admit the little prince’s wisdom. In Flight to Arras, Saint-Exupéry reverses the order, remembering his fellow pilots at the beginning of the book as boys in school, full of life and the promise of the future, waiting – but for what? – and then, in an instant, they are men, called out of the classroom to receive the order to fly futile, suicidal sorties that will reveal the same sad fact – the Germans are advancing on Paris. The war, for now, is lost. Irony and futility characterize Flight to Arras, a classic story of young men cut off in their prime through the stupidity of war, a book that brings him in line with Camus, Sartre and the Existentialists.

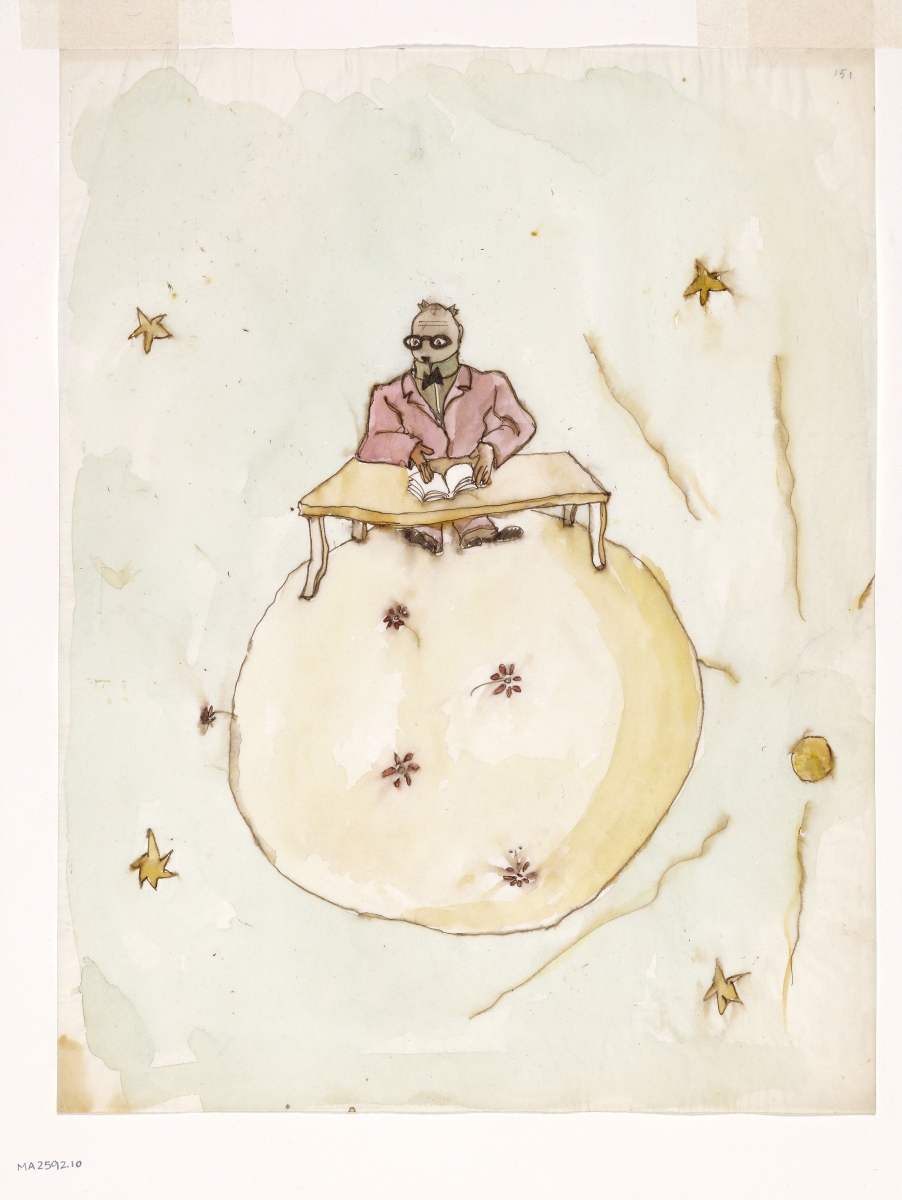

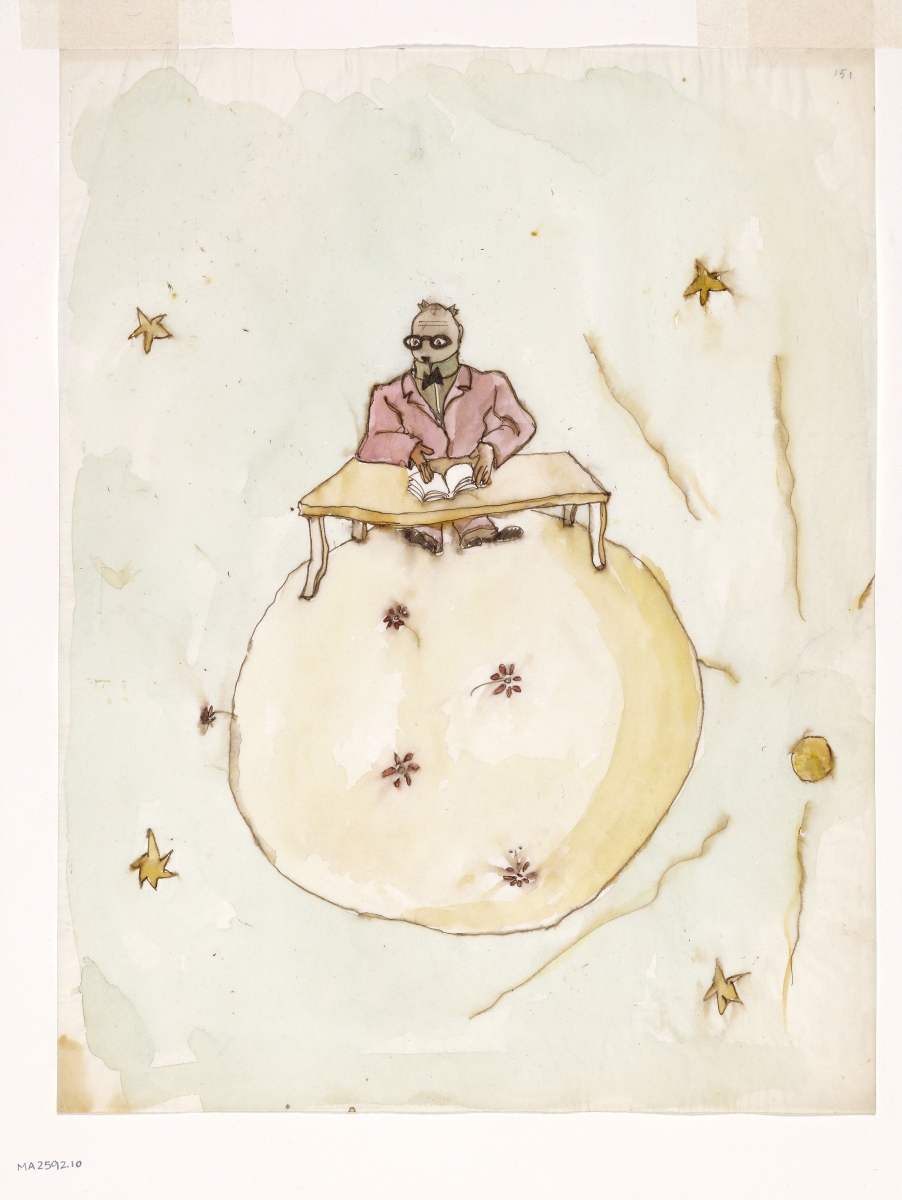

“Le businessman sur sa planète (The businessman on his planet)” by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, New York, 1942, watercolor and ink on onionskin paper, overall: 11 by 8-3/8 inches. Purchased on the Elisabeth Ball Fund, 1968.

What is of great interest in a comparison between The Little Prince and Flight to Arras are the illustrations. Saint-Exupéry did not illustrate Flight to Arras. Bernard Lamotte’s black and white, pen and ink wash drawings mirror Saint-Exupéry’s words, conveying a stark, hurried, journalistic realism, as if they were done on the run in an attempt to get the feel of retreat, and of profound loss, down on paper before it’s too late. In contrast, Saint-Exupéry’s line drawings for The Little Prince are little more than doodles, the kinds of drawings a father might make to illuminate a story he is telling his child – or that a child might make in order to help tell a story to a grownup.

Saint-Exupéry’s disappearance in 1944 was a sensation that echoes the disappearance of the little prince at the end of the story and spun a myth of sorts around the aviator and author, as if he were an Icarus who never fell, who just kept flying, and is still flying. A spirit of the air who returned to the air, just as the little prince was a boy who fell to Earth from space and returned to space, shedding one form for another. The discovery of Saint-Exupéry’s identity bracelet, complete with the name of his New York publisher, Reynal & Hitchcock, and of some of the remains of his P-38 holds a bittersweetness, taking away more than a soupçon of the romance of his story. They remind us that Saint-Exupéry was a human being, and that, perhaps, our projection of romance onto him, says more about our wishes than it does about his life and life’s work. It might take a child to help us make sense of this.

“The Little Prince: Taking Flight,” will be on view through January 15 at the Morgan Library & Museum, at 225 Madison Avenue. For information, www.themorgan.org or 212-685-0008.