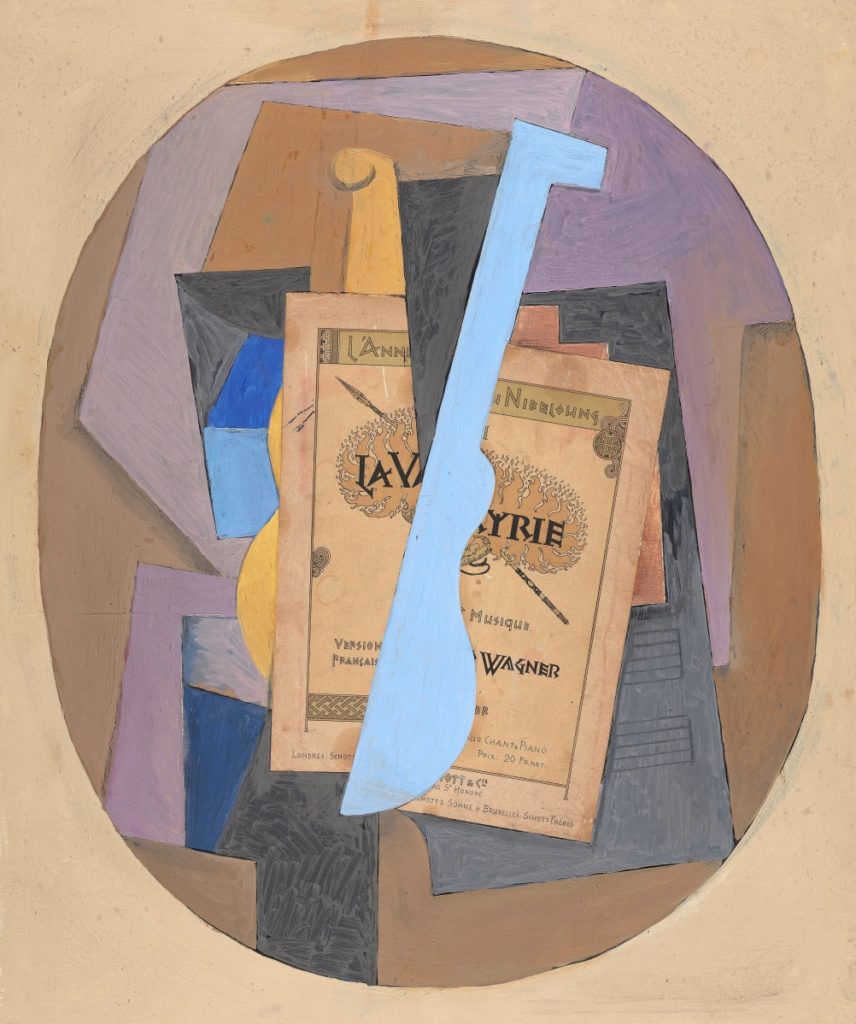

“The Ring” by Suzy Frelinghuysen (American, 1912-1988), 1943, oil and collage on Masonite. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, J. Harwood and Louise B. Cochrane Fund for American Art. ©Frelinghuysen Morris House & Studio, Lenox, Mass. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

By W.A. Demers

RICHMOND, VA. – If guitars could tell their stories, oh, what sagas they might relate – “In life I was silent, in death I sing,” they might say, bringing to mind the incredible journey of the late Tony Rice’s Holy Grail Martin D-28. Art Dudley tells it in the April 2016 issue of Fretboard Journal. Number 58957 off the C.F. Martin assembly line, that 1935 guitar’s place in the history of American music became the stuff of legend. A new exhibition on view at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA) to March 19, 2023, puts the quintessential American instrument up on the easel. “Storied Strings: The Guitar in American Art,” comprising 125 works of art created over the span of nearly 200 years, is the first exhibition to explore the guitar’s symbolism in American art from the early Nineteenth Century to the present day.

The museum’s Louise B. and J. Harwood Cochrane curator of American art Dr Leo G. Mazow assembled the exhibition’s works of art with a view toward tracing how the guitar, as a visual motif, has long enabled artists and their subjects to address topics and tell stories that would otherwise remain untold or undertold.

The show’s works of art pair prominent American artists working in media ranging from paintings, drawings, watercolors, photographs and sculptures with their musical muses, punctuated throughout with a total of 35 guitars, including those made by Fender, Gibson, Gretsch and Martin and played by such pioneering musicians as Eric Clapton, John Lee Hooker, Freddie King and Les Paul.

“As with music, the guitar in visual art is both a storyteller’s companion and a tool through which topics are addressed,” said Mazow. “The guitar is uniquely capable of symbolizing both poetic and prosaic themes. Because of its portability and relative affordability, the guitar appears in myriad settings and situations. It frequently intersects with matters of race, ethnicity, class, gender and disability, including blindness.”

“Home Ranch” by Thomas Eakins (American, 1844-1916), 1892, oil on canvas. Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of Mrs Thomas Eakins and Miss Mary Adeline Williams.

William H. Johnson’s (1901-1970) “At Home in the Evening,” circa 1940, depicts three individuals, perhaps a family, in his powerful folk style standing outside a rural dwelling, one of them cradling a guitar in his hands. Determined to “paint his own people,” Johnson also celebrated African American culture and imagery in the urban settings of pieces, such as “Street life – Harlem, Café” and “Street Musicians,”

The trope of woman with guitar was abundantly captured in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century American art, represented in this show with several examples, including “Jessie with Guitar,” 1957, by Thomas Hart Benton (American, 1889-1975); “Julie,” 2006, a model with prop by Sue Hudelson (American, b 1967); folk singer Odetta soulfully becoming one with her instrument in Otto Hagel’s (1909-1973) gelatin silver print from 1958; and Thomas Cantwell Healy’s (American, 1820-1889) portrait of Charlotte Davis Wylie, 1853. According to Patti Carr Black’s book, Art in Mississippi, Healy, described as an “eminent painter of portraits,” (1820-1889), in 1844 settled in Port Gibson, a prosperous community able to support the resident artist with commissions. Elizabeth P. Reynolds, curator of an exhibition of his work at the Mississippi Museum of Art in 1980, located more than 40 portraits that Healy had painted in Port Gibson.

American documentary photographer and photojournalist Dorothea Lange (1895-1965), who scoured America during the Depression capturing and humanizing its effect for the Farm Security Administration, takes the guitar out of the parlor and puts it in the hands of “Coachella Valley Mexican Laborers around Camp,” 1935, The young Mexican farm worker plays guitar and sings a corrido, or Mexican folk ballad, one of the strongest artistic expressions of Mexican culture. One such corrido translated into English laments, “In these unhappy times/depression still pursues us/lots of prickly pear is eaten/for lack of other food.”

In “Girl with Guitar,” 1965, Robert Gwathmey (American, 1903-1988) evokes Americana emanating from one’s front porch, the quintessential portable entertainment that a small acoustic instrument provides, and this is also captured by Thomas Eakins’ (American, 1844-1916) “Home Ranch,” 1892, where we see a rhapsodizing cowboy perched on a stool, guitar rather than pistol in hand.

“Woody Guthrie” by Al Aumuller (American, active 1930s-early 1950s), 1943, gelatin silver print. Prints and Photographs Division, The Library of Congress, Washington DC.

“Goodnight Irene,” the Twentieth Century American folk standard first recorded by American blues musician Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter in 1933, is the subject behind Charles White’s (American, 1918-1979) 1952 oil on canvas that portrays Lead Belly playing that song with an ardent admirer looking over his shoulder. The painting was once in Harry Belafonte’s collection, and the singer said of White’s art, “Through his paintings, I was inspired to find the songs that equaled what I saw his paintings reflect. And in looking for what his paintings reflect, I was able to discover Lead Belly. And discovering Lead Belly, I discovered language. Here was a culture and a life and things being expressed that had no space in popular American entertainment. The passion and the bitterness of the protests. And I said, that’s my man. I’m gonna do what he’s doing. My first repertoire was made up of Lead Belly songs, I used to do it at any little party, any little place.”

“This Machine Kills Fascists” reads the label that American folk singer/songwriter Woody Guthrie affixed to his guitar. The 1943 gelatin silver print by Al Aumuller (American, active 1930s-early 1950s) shows Guthrie in a half-length portrait, facing slightly left, holding the guitar used to bring truth to power in protest music that began with decrying conditions in Depression America’s Dust Bowl and migrated to its city streets in the 1960s and 1970s.

No exhibition of the guitar as artistic symbol could afford to ignore its symbology outside of the musician who wields it. The strings of a guitar vibrate. And so does the entire image of Spencer A. Moseley’s (American, 1925-1998) “Gervais’ Guitar,” 1964, an acrylic on canvas. Not well known, Moseley, who was born in Bellingham, Wash., and earned both undergraduate and graduate art degrees from the University of Washington, was a pivotal figure in the Washington art scene. His works embraced Modernism, abstraction, cubism, Pop and Op art, and a variety of variations throughout his career. What they have in common is bold color and strong outlines, evident here in an image that virtually thrums with imagined sound.

In Suzy Frelinghuysen’s (American, 1912-1988) “The Ring,” 1943, the guitar’s form becomes an ornamental device where the skill of the artist visually alludes to a sonic experience. Or in Romare Bearden’s (American, 1911-1988) “Three Folk Musicians,” 1967, a collage of various papers with paint and graphite on canvas, which is in VMFA’s own collection, where the guitars, stripped of any detail, become part of the pattern expressing the story of Black music, designating identity, pride and achievement. Finally, as in “Person with Guitar (Blue),” 2005, by John Baldessari (American, 1931-2020), where it literally is the “blues.”

“The Music Lives After The Instruments Is Destroyed” by Lonnie Holley (American, b 1950), 1984, burned musical instruments, artificial flowers, wire. Souls Grown Deep Foundation, Atlanta. ©2022 Lonnie Holley/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City. Photo: Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio.

Then there is the guitar deconstructed. Lonnie Holley (American, b 1950) treats the viewer to a montage of burned musical instruments, artificial flowers and wire in “The Music Lives After The Instruments Is Destroyed,” 1984.

American artists represented in the show include Baldessari, Bearden, Benton, Elizabeth Catlett, William Merritt Chase, Thomas Eakins, William Eggleston, Robert Henri, Lonnie Holley, Frances Benjamin Johnston, William H. Johnson, Jacob Lawrence, Annie Leibovitz, Charles Willson Peale, Ruth Reeves and Julian Alden Weir.

Audio-visual kiosks featuring music and filmed performances are included to enhance the visitor experience. A window overlooking an impressive, fully functioning recording studio, installed in the exhibition in partnership with In Your Ear Studios, lets visitors view guitarists of national and regional renown as they record songs that demonstrate the power of the instrument to tell stories [See accompanying story].

In addition, a comprehensive 276-page exhibition catalog can be purchased in the VMFA Shop, online at www.vmfashop.com and distributed by Penn State University Press. Authored by Dr Mazow, the catalog features color images of every work of art in the show and features contributions by Jayson Kerr Dobney, the Frederick P. Rose curator in charge of musical instruments at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Dr Phil Deloria, the Leverett Saltonstall professor of history at Harvard University.

The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts is at 200 North Arthur Ashe Boulevard. For further information, www.vmfa.museum or 804-340-1400.