Installation view of “As The World Weds: Global Wedding Traditions.” Courtesy Kent State University Museum.

By Laura Layfer

KENT, OHIO – “As The World Weds: Global Wedding Traditions” is currently on view at the Kent State University (KSU) Museum. Whereas white gowns customarily comprise a significant part of its holdings, this new exhibition highlights diversity in ceremonial garb. It also examines the progress in what defines a union, from objects of adornment, and their importance, to the religious, cultural, financial and legal implications they represent in the act of two individuals committing one to another.

The KSU Museum was established on campus in 1985, in a 1920s Beaux Arts building, formerly a library, and later, administrative offices. Its founding collection of 4,000 costumes, textiles and accessories, along with thousands of additional books and decorative objects, came from New York City designer Shannon Rodgers and Jerry Silverman, the latter being the namesake of the duo’s fashion business and manufacturing label. Their Seventh Avenue firm offered dresses over many decades, known for a ready-to-wear style with a signature practical flair. They amassed a treasure trove of historical artifacts that dated back centuries, first offered to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, KSU ultimately created a welcome home and was linked to Rodgers’ Ohio roots. Other large contributions, such as the Tarter/Miller assemblage of glass, have added to the scope of presentation.

“We have a lot of wedding dresses,” says Sara Hume, professor and curator at KSU Museum, “when you think about a piece that is typically worn once and almost always saved, carefully stored and often passed down to the next generation, the surplus makes sense.” She says inquiries for acquisitions come frequently, adding variety and depth to the range of potential for her planning of this show. It considers how the concept of wearing white, said to have originated from Queen Victoria’s gown at her marriage to Prince Albert in 1840, influenced the future of an industry that continues to expand today. “There is the iconic image of the dress and implications of privilege from the Nineteenth Century that became mainstream in consumer culture of the Twentieth Century,” notes Hume. “Rural Europeans viewed wedding clothing as a multipurpose purchase that would transition post-ceremony into a useful ensemble for parties, church and other special occasions.” This seems to have been a precursor to the notion of sustainability, not to mention practicality and the inclination towards buying or selling second-hand clothing.

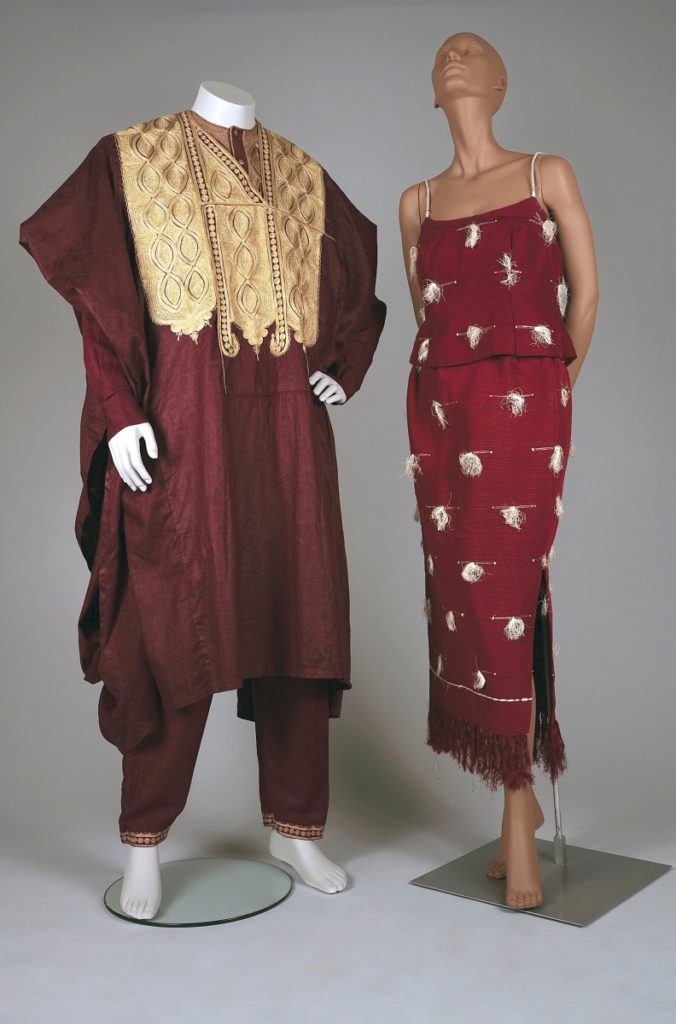

Wedding outfits from Ghana, 2003.

Alternatively, there have consistently been an abundance of rituals that recycle in myriad forms or have become a standard societal norm. Why is white worn only for engagement photos in China, but in the United States the color would rarely be visible, even possibly considered bad luck, until the actual special day? When did fashion houses begin marking the finale of a runway show with a supermodel strutting down as a bride in the ultimate pièce de résistance? How did the roles of attendants, from bridesmaids and groomsmen to flower girls and ring bearers, come to be wedding party regulars? Has there always been so much interest put into the mother-of-the-bride’s outfit? And when did the exchange of a dowry, or the trousseau of linens, lingerie and a honeymoon wardrobe, come into use? The gallery is divided into themes that elaborate on all of these aspects as well as the others. For instance, the origin of the 1871 British folklore of “Something Old; Something New,” its persistence and evolution over the ensuing century, as well as other traditions, are explored.

One donation, a wedding dress from 1947 made of silk from a parachute used by the bride’s brother during World War II, is in stark contrast with the dark velvet cape and sleeveless 1970s Halston dress, selected for a second marriage after the betrothed spotted it on actress Elizabeth Taylor. Whether dictated by need or desire, the styles are clearly a matter of personal choice, even when incorporating common motifs and representations. A 1930s-40s long dramatic lace veil is embellished with orange blossoms, a symbol of purity and fertility that harkens back to ancient China. Nearby, an elaborate floral brocade Japanese outer kimono, known as an uchikake, is a form that signifies the transition from bride to wife as its feature of elongated and exposed sleeves is associated exclusively with unmarried women. A red sari on a mannequin weaves gold accents, customary detail employed in India, and a handwoven embroidered three-piece ensemble from Ghana, where the groom is expected to have a one-of-a-kind ceremonial creation.

There is also a focus on the decorative structural and design elements that evolve with the wedding event itself. A chuppah, the canopy-like structure under which a Jewish couple marry, constructed by four poles, is displayed. It is juxtaposed to the more private tsutsugaki yogi, a nuptial bedspread, given from the groom’s family in Japan, this one shown bearing phoenixes.

“I spent a lot of time looking at bridal magazines and social media in my deep research,” laughs Hume. “There are so many facets that we really had to narrow our scope, looking at things like pre- and post-war impact, female vs male couturiers, and a shift in conventions, particularly the enactment of the Marriage Equality Act.” A star of the show is a vintage lace wedding dress with a pretty pink under sheath made by Fontana, an Italian women-owned fashion house popular in the 1950s, with patrons such as Princess Grace of Monaco. The donor wore the dress, when she married in North Carolina in 1956, an example of a trend of Americans frequently favoring designs from abroad. Locally, matching his-and-her glen plaid suits on view were made by a tailor in Canton, Ohio, in 1946, and donated by the wearers’ daughter in memory of her parents. Additionally, on loan were wool jackets, trousers and ties, slightly varying in shade and pattern, worn for a courthouse matrimony shortly after same-sex marriage was legalized in 2015. Hume even sourced a Twenty-First Century judge’s robe to share the proper attire donned by those officials authorized to marry people.

Alsatian wedding ensemble and headdress, 1908.

Throughout the exhibition are images and information about on many of the real-life couples that wore the pieces displayed. Formal to casual, intimacy vs the mainstream media’s attention to reality television programs on the topic of bachelors and marriage these days, Hume’s goal was to distill the commercialization from the classics. The common denominators in all the offerings are the love, legacies and family heirlooms, which endure across continents, cultures, economic status and gender, all emblematic of the dedication of the wearers to each other.

“As The World Weds: Global Wedding Traditions” will be on view at the Kent State University Museum through August 27.

The Kent State University Museum is at 515 Hilltop Drive. For further information, 330-672-3450, museum@kent.edu or www.kent.edu.

_ksum_1983.1.jpg)

1986.27.1_3q_front.jpg)