In recent months and years, the discovery or recovery of stolen or missing works of art and objects – including snuff boxes stolen from Temple Newsam 40 years prior or an Anglo Saxon brooch returned to the museum it was stolen from after nearly 30 years – has occasionally made headlines in art news feeds around the world. Our interest piqued, we wanted to know more about the team behind these headlines and reached out for a behind-the-scenes glimpse. Julian Radcliffe, the firm’s founder and chairman of Art Loss Register indulged us with the following interview.

For readers who aren’t familiar, what exactly IS Art Loss Register?

The Art Loss Register (ALR) is the recognized international searchable database of stolen, looted, missing, damaged, in dispute, at-risk art and antique items which enables the art trade, police, insurers, lenders and collectors to undertake due diligence before they become involved with objects to ensure they are clear.

How does ALR differ from, say, Interpol’s database?

The Interpol database is limited to those objects which individual national police forces feel are worth circulating and entering on the database and tend to be items of national importance, publicly owned and circulated quite late. The total number of items is far smaller than is on the ALR and there is no follow-up to matches or control of who uses the system. There is no real impediment to criminals searching and finding out if the item which they wish to offload is registered and then working out how to sell it with the lowest chance of being caught. The ALR database can only be searched by ALR-trained staff, on behalf of searchers who have to sign a contract to cooperate when an item is matched as stolen, reveal their identity, pay the fee and a full audit is maintained of the searches. This enables the art trade to demonstrate due diligence, and in the event of a match, the ALR staff follow up with the searcher.

When and why did you start Art Loss Register?

I claim no credit for the idea, which came from Sotheby’s when I was helping them protect their staff from kidnap and similar risks in the late 1980s. We had reduced the risks and the ransom amounts, and they asked if we could do the same for stolen art. They had started supporting a not-for-profit organization in the New York International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR) which was trying to computerize paper records of thefts. They did not have any support from the insurance industry which was my background, and I had the experience of working with law enforcement. I managed a feasibility study which led to the raising of finance and the creation of the ALR in 1990 with Sotheby’s, Christie’s, Lloyd’s of London, venture capital and IFAR as shareholders.

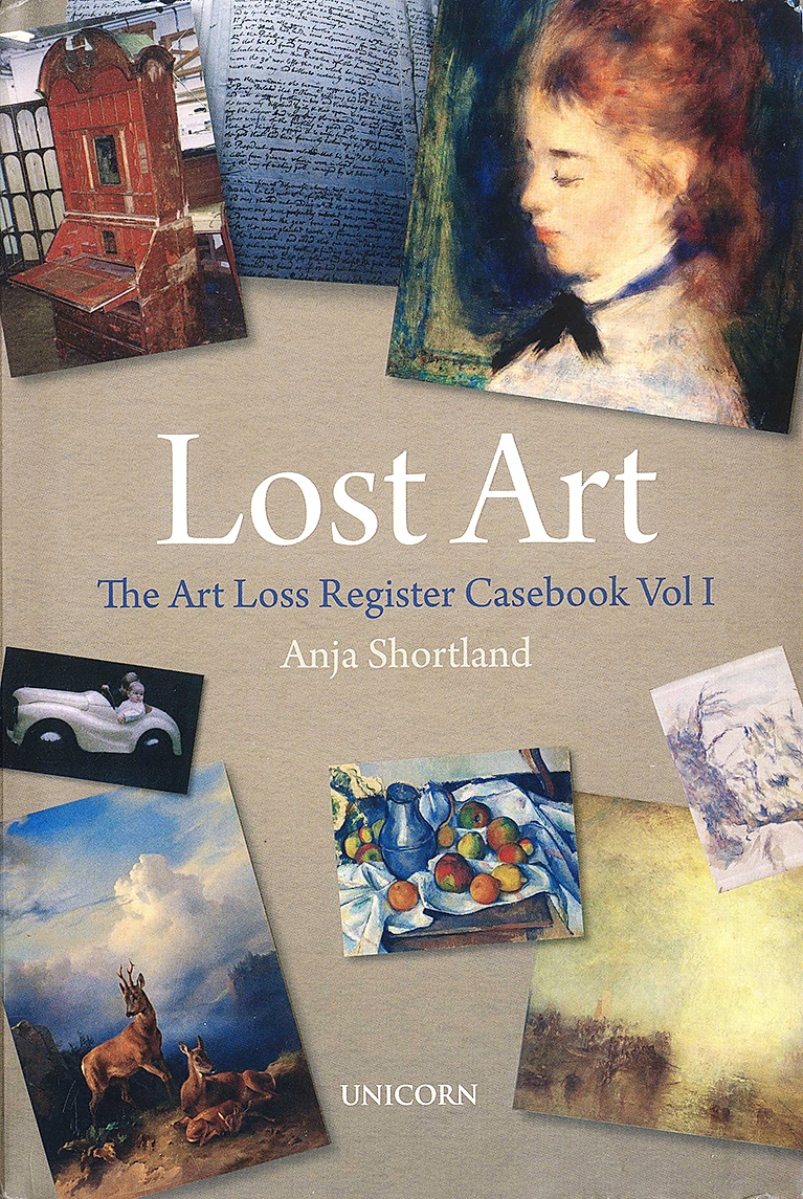

Lost Art – The Art Loss Register Casebook Volume 1 by Anja Shortland. Published by Unicorn, London, 2021.

Can you tell me a little bit about the team at Art Loss Register?

We have about 50 people on the team, 35 in an office in India. Over 20 years, we have developed a team of people there who have been working for a very long period of time who are experts in searching and registering items. Recently one of our top people has gone to India to oversee training AND more searching, aided by a new IT system. We also have German and French speakers who can search those relevant auction houses. Some have a specialization in various categories including restitution. A basic searcher must be able to search every lot in the catalogs.

If someone – an individual, auction house or dealer – wants to work with ALR, describe the process. What can someone expect when they work with ALR?

The threshold of value is $2,000 and we have various different categories people will register under. One is conventional theft, for which we need a police report number and an insurance claim number. Another is World War II Nazi and Holocaust searches. There are many other similar events in wartime or during difficult political climates where items might be repatriated. Some obvious examples of that are the Benin Bronzes, which were looted, but also hundreds of other items that have been bought or exported by Western people working overseas for hundreds of years. The relation to illegal export may not be clear. There are also items ‘in dispute’ because of will, disputed trust, divorce or commercial transaction gone wrong – pictures, silver, whatever. If there is evidence of a genuine dispute, we will record the item in dispute. Then we record items that are being used as security by the banks when they are lending but not keeping the item in their vault.

Most registration of losses and searches are submitted via the website, but our staff monitors all cases and are very active in assisting. The client will sign a contract and pay the fee and are required to give disclosure of relevant facts which will then become part of the ALR certificate of search. A searcher has to have a bona fide interest in the item, i.e., as a buyer, lender or insurer. The search is specific to one item and the client cannot scan the contents of the database.

We depend on two things for success: people must record losses with us and the police, and buyers and sellers searching to make sure whatever they are offering for sale – or looking to buy – is not stolen or fake.

How are fakes dealt with?

We register everything in our main Art Loss Register database. We record fakes under any of those headings where we are given an authoritative view that they’ve been offered a fake; an example of that would be if a qualified dealer says I’ve been offered a fake Rolex and its number is “X” and it’s offered somewhere else we can then warn them. It must be something uniquely identifiable – not necessarily with a number – when an item is photographed you can identify the object with certainty.

Take an artist like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot; often, he had a man with a red coat in his landscapes. It’s known that when he died, large numbers of people began making pictures similar to his and there are many fake Corot [paintings] on the market. Some are known to be fake, and they can be recorded as fake on our database.

What is the cost/expense to the individual or business to sign up with ALR?

The cost for an auction house is based on the number of lots searched and ranges from $2,000 for the smaller to six-figure values for the largest. Dealers tend to buy bundles of searches which range depending on volume from $60 to $30 per search. For a victim to register a theft is $20 with a discount for volume and if the loss is insured there is no charge to the victim. A recovery fee may be charged based on the ultimate net benefit to the victim from the recovery i.e., after all costs incurred. Museums and not-for-profits may be given discounts and services to law enforcement are free to them.

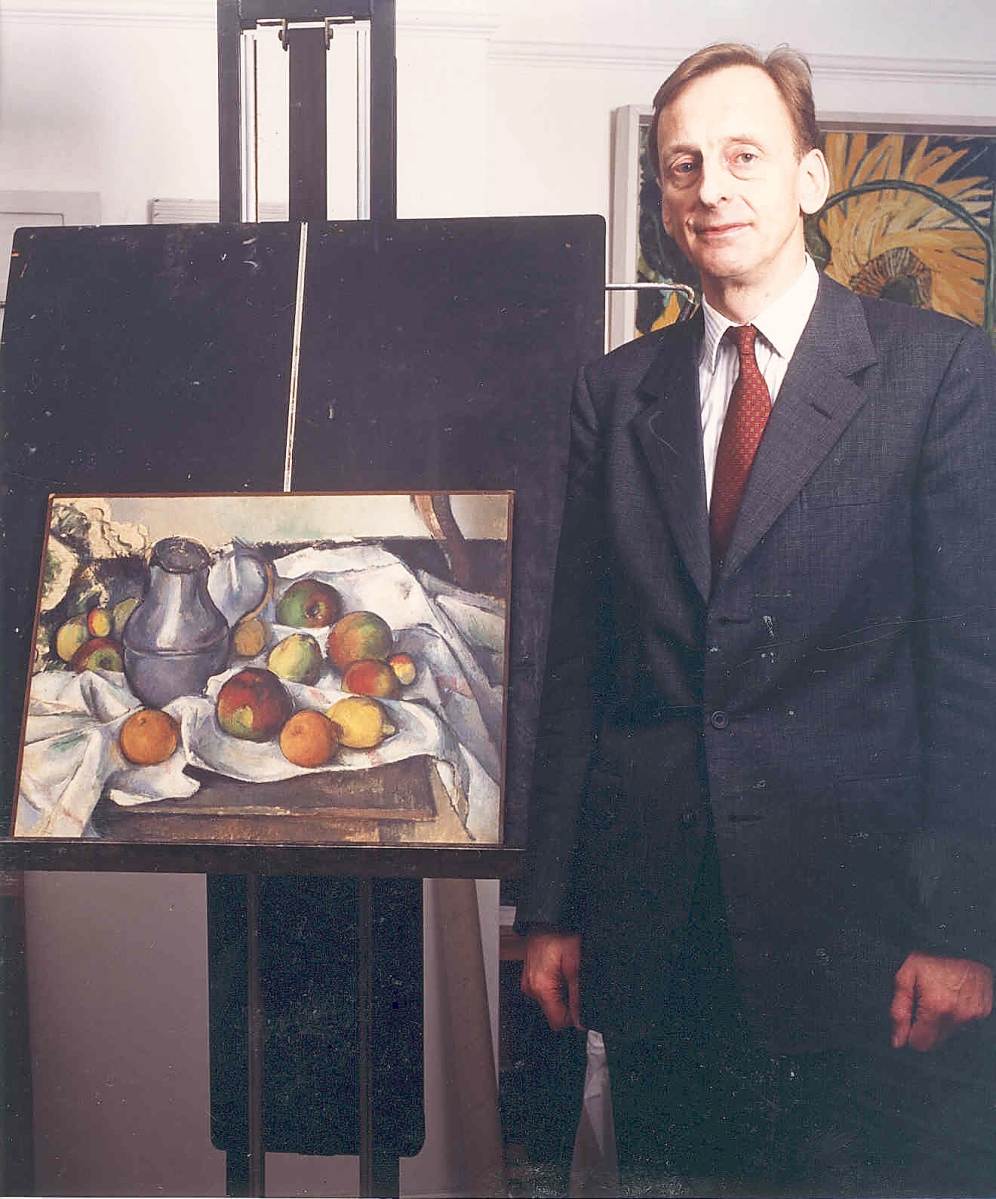

Julian Radcliffe with the recovered “Bouilloire et Fruits” by Cezanne.

What was your first significant recovery? Can you tell us a little bit about that?

The recovery which had the greatest impact was that of a Cezanne valued at $30 million and resold recently for $60 million. It was stolen in Massachusetts in 1978 with six other paintings and disappeared for 20 years. The thief had been shot by another criminal and was never tried. The pictures had been given by the thief to his lawyer as a fee to defend him on a gun charge and the lawyer took the pictures to Switzerland and hid them for 20 years. He then tried to sell them or claim a reward. I negotiated against this unknown person and by subterfuge obtained his identity so that he was arrested and jailed for seven years, and all the pictures were recovered in 1999.

Since then, what are some of the other pieces you’ve helped recover?

They include furniture, scientific instruments, toys, jewelry, carpets, guns and values range from $1,000 to millions. We expect to recover about 400 stolen watches per year and the number is increasing rapidly.

Are watches among the most stolen objects? Why?

The number is going to be probably 1,000 in a couple of years. More of the online watch platforms are searching with us, and we’re doing more searches of auction houses and smaller dealers and pawnbrokers. I would say the number is almost a direct relation to the number of searches.

What is one of the most unusual items ALR has been asked to recover?

ALR staff, running a routine check, found the pedal car in Christie’s Melbourne decorative arts catalog in July 1999. The pedal car was one of 700 pedal cars produced by the Austin Car Company from the 1950s through to the late 1960s, and it was valued at £1,500. It was stolen from the garage of a private house in Surrey in the summer of 1998 and showed signs of hard wear. The owners supplied a photograph taken just a month before the car went missing. This revealed a pattern of rust spots and scratches which, with the license plate number, proved the items were identical. On its own, the car probably would not have made it to Australia but consolidated as part of a larger shipment of stolen goods. The ALR searchers then looked more closely at the rest of the catalog and found listed a number of other items that had been stolen in the south of England at around the same time – in particular, pieces from a collection of porcelain that was part of a £200,000 burglary in Oxford. Therefore, ALR liaised with Interpol and United Kingdom police, and two antique dealers were arrested in September 1999 in the South of England as a result. A vast hoard of fine and decorative art was seized, these items numbered several hundred. Among these items the Art Loss Register identified was an important collection of bronzes stolen from a dealer in Paris in 1998. It is believed that all these items, many of which have been stored for a number of years, are stolen.

Watches such as this one have been

searched for on ALR.

Do you work with local, state and international law enforcement?

We work with law enforcement in many countries, e.g., United Kingdom, France, Germany, United States and Canada, and some of our recoveries are described in Lost Art – The Art Loss Register Casebook Volume 1 by Professor Anja Shortland of Kings College London which can be ordered via Amazon.

Is the work dangerous?

Even when we’re dealing with people with criminal records, it would be very foolish for them to up the stakes by assassinating us. Most people involved in stolen art may have been involved in very unsavory crimes, but they are reticent to get involved with violence.

Why is it important for more people to research the provenance of works?

Provenance is critical in proving authenticity and preventing fakes and forgeries. Ideally, a complete record or ownership, location, exhibition, publication, restoration, etc, gives a detailed and interesting provenance which enhances value by providing the story, confirming legal title and assisting with future conservation.

Are the majority of your clients from the UK/Europe or is your client base spread fairly evenly worldwide?

We have to be truly international since the Art Trade is and so are the criminals, and more than half of the higher value recoveries are made in a different country to that of the theft, often having gone through many others. We have 19 US auction houses using us out of a total of 155 worldwide and expect to sign up many more. As the largest art and watch market, we have to be better represented but we cover all the leading auction houses, the two leading art fairs and many US dealers, museums and collectors. We are very actively supporting the banks who lend to art and law enforcement, the FBI, NYPD, Department of Homeland Security and the District Attorneys. My colleague Alexandra Foley, who worked at Sotheby’s, will be traveling the United States extensively.

– Madelia Hickman Ring