Commeraw stamped his name and address on many of his vessels, an early and highly effective instance of branded pottery in New York. He used swags and tassels to create his signature “clamshell” or “bowknot” motifs. Detail, 3-gallon jug by Thomas W. Commeraw, circa 1800-19. Collection of Joseph P. Gromacki. Courtesy Crocker Farm.

By Laura Beach

NEW YORK CITY — As A. Brandt Zipp recalls, it was around New Year’s Day in 2003 when he made a discovery that had eluded researchers for nearly a century. Thomas W. Commeraw (circa 1771-1823), long credited with some of the most artistically striking salt-glazed stoneware made in New York City, was, alone among his competitors, a free man of color. The truth lay hidden in plain sight, recorded not only in the ledger entry Zipp uncovered in New York City’s 1800 Federal census records, but also suggested in overlooked documents relating to Commeraw’s social activism and his participation in an ill-fated mission to establish a Black republic in West Africa in the 1820s. Zipp recounts the extraordinary saga in unprecedented detail in his book Commeraw’s Stoneware: The Life and Work of the First African-American Pottery Owner, published by Crocker Farm in September 2022.

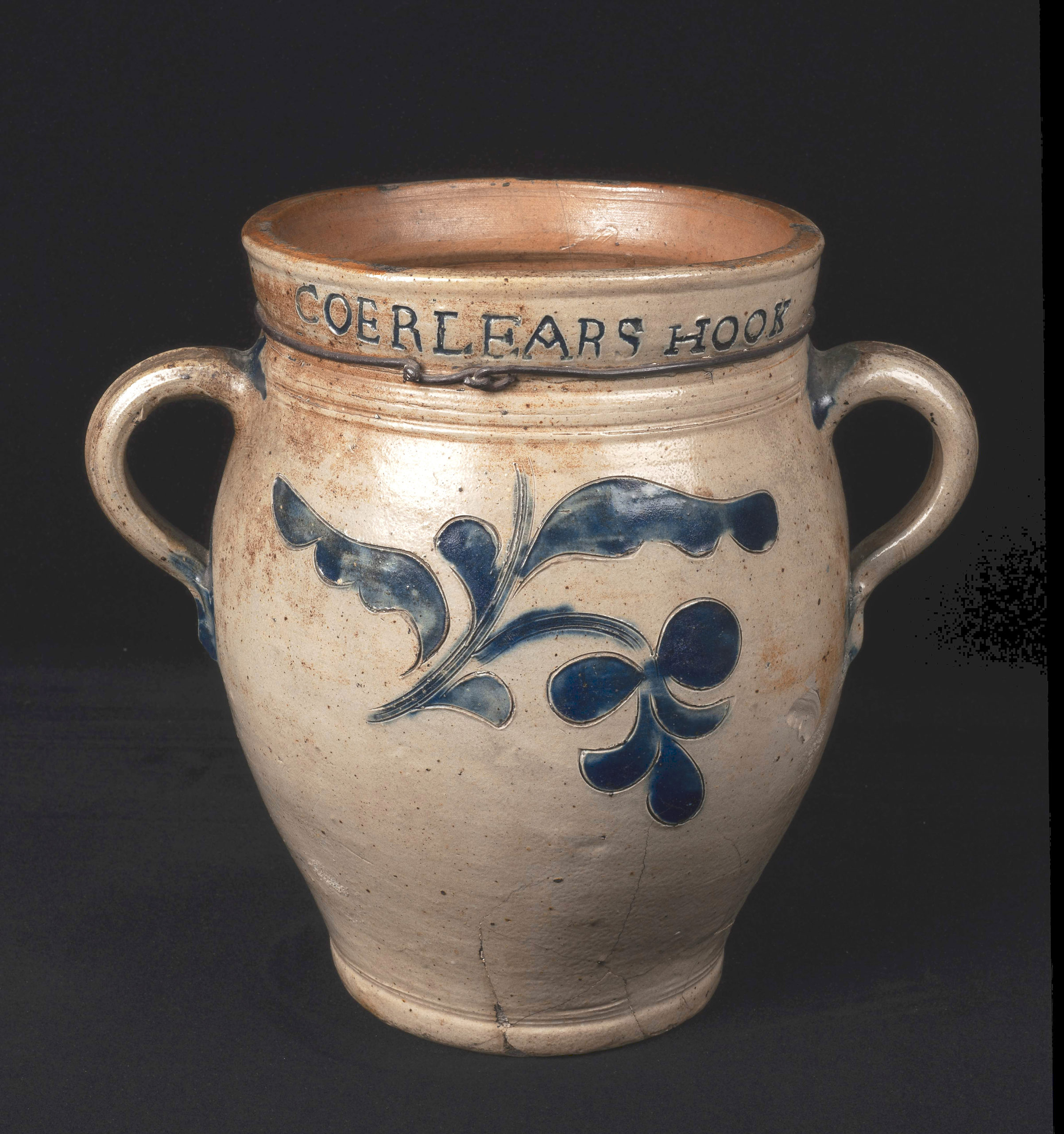

Born enslaved and probably trained in the Crolius workshop, Commeraw was freed in 1779 following the death of William Crolius. Commeraw first appears in the New-York Directory and Register of 1795. By 1797, he had his own kiln at Corlears Hook on Manhattan’s East River and by 1799 owned his home, a rarity for any craftsman of his time. Perhaps influenced by business reversals following the War of 1812, Commeraw in 1820 sailed to Africa with roughly 80 Black settlers. When the experiment organized by the American Colonization Society (ACS) failed, the recently widowed Commeraw returned to the United States with his children. Acknowledged in his obituary as “a descendant of Africa” who “carried on an extensive business in New York, where he was very generally known,” Commeraw died in Baltimore in 1823.

Zipp’s study grew out of his near lifelong interest in stoneware. A partner in Crocker Farm, the Maryland-based specialty auction house, Zipp had long immersed himself in census records, city directories and newspapers. He began investigating New York pottery as an outgrowth of his family’s deep interest in the Remmeys of Baltimore and New York. He reflects, “So much of what my brothers and I know about pottery we just absorbed as kids while helping our father, who was buying and selling. It was like learning a foreign language.”

Commeraw’s Stoneware: The Life and Work of the First African-American Pottery Owner fashions a vivid picture of Commeraw’s world and that of his competitors in lower Manhattan. New discoveries fill the pages of the profusely illustrated volume.

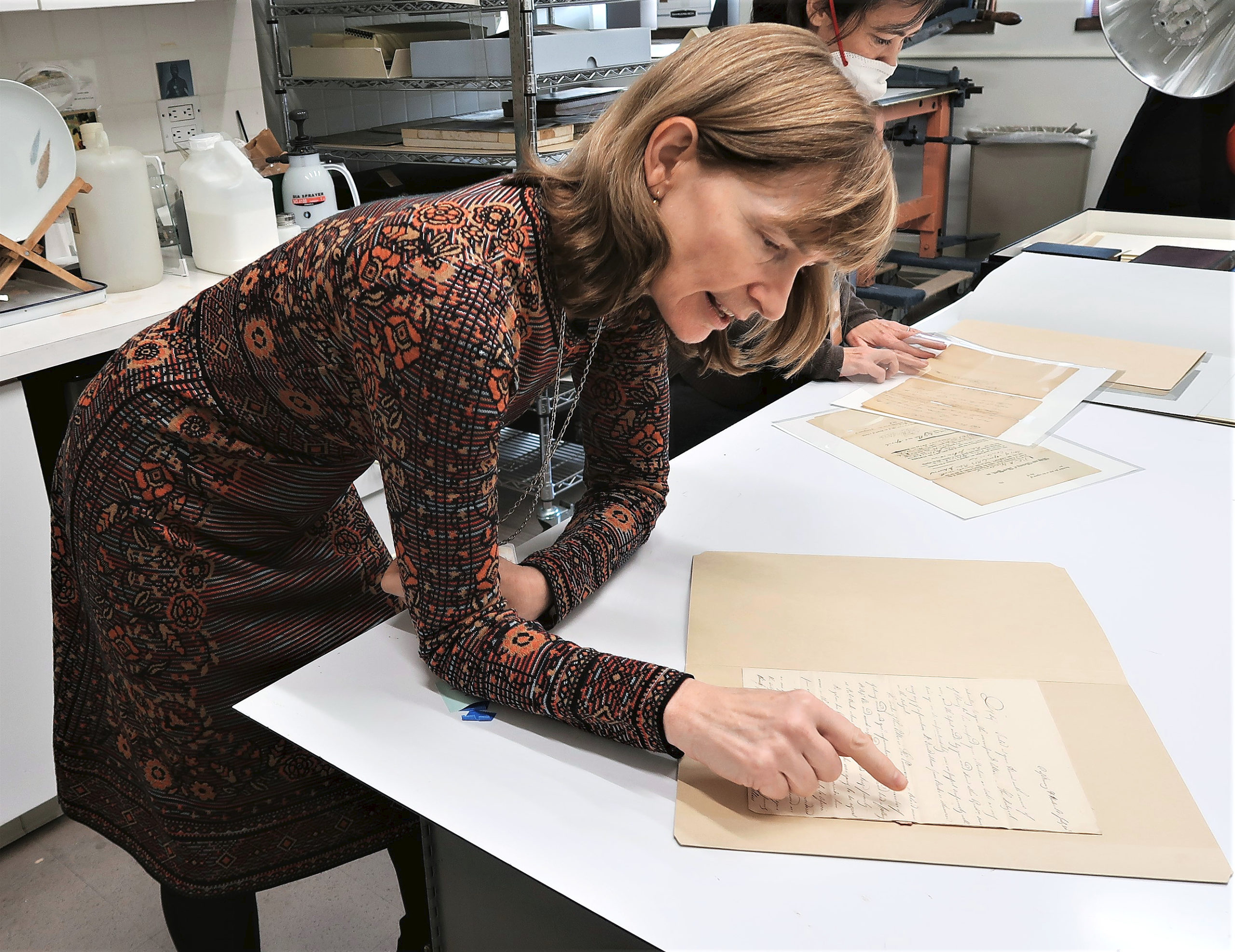

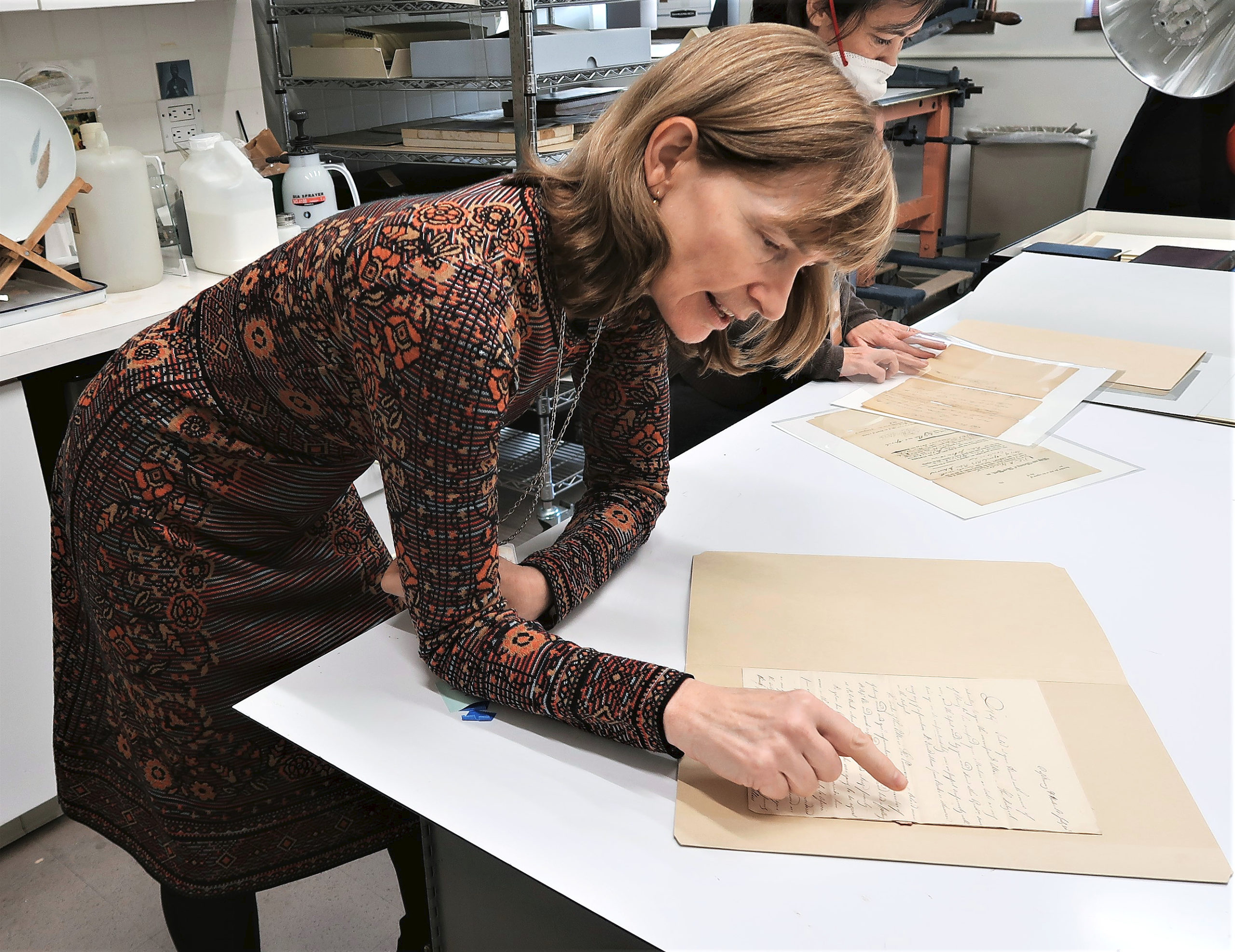

N-YHS vice president and museum director Margi Hofer examines a letter dated July 20, 1821, from Rev. Henry James Feltus, Commeraw’s pastor at St Stephen’s church, to Peter A. Jay providing insight into the potter’s motivations for emigrating to Sierra Leone. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society. —Laura Beach photo

One of the author’s favorite pieces is a jug stamped “Ashmore’s Genuine Cordials,” made by Commeraw for distiller Ann Ashmore, whose colorful story Zipp relates in detail. “Advertising jugs have a long history, but this is the earliest American example we’ve been able to identify,” he says.

Alternate spellings of the potter’s name notwithstanding — probably of African origin but often assumed to be French, it appears in contemporaneous records as Commereau, Commereor, Commonerau and Lamoreaux — it remains unclear why researchers failed to connect Commeraw with his published record of social activism. For Zipp, the discovery came on Christmas Eve in 2006, when he found on eBay a newspaper reprint of a letter sent by Commeraw from the African coast. He was also excited to uncover the ACS’s handwritten emigration register, on which Thomas “Camaraw” is listed as a 45-year-old potter, just above the names of his wife, children and his wife’s siblings.

The findings of Zipp and other researchers come to life in “Crafting Freedom: The Life and Legacy of Free Black Potter Thomas W. Commeraw.” Organized by Margaret K. Hofer with studio potter and independent researcher Mark Shapiro and Mellon Foundation postdoctoral fellow Allison Robinson, the exhibition on view at the New-York Historical Society (N-YHS) from January 27 through May 28 draws from major public and private collections to recreate the craftsman’s milieu — more than a dozen potters worked in lower Manhattan in the first two decades of the Nineteenth Century — and places within it Commeraw’s unlikely story.

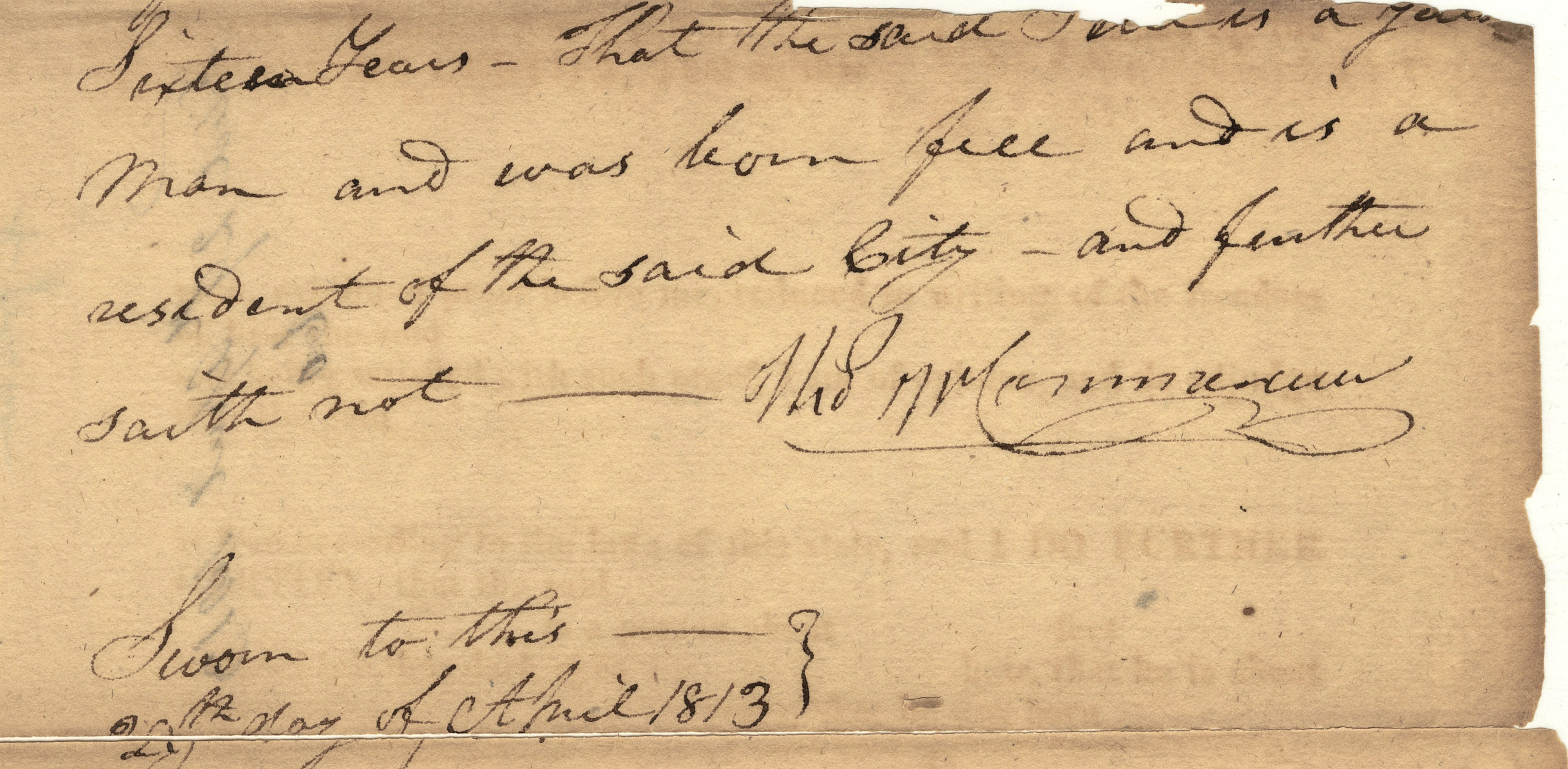

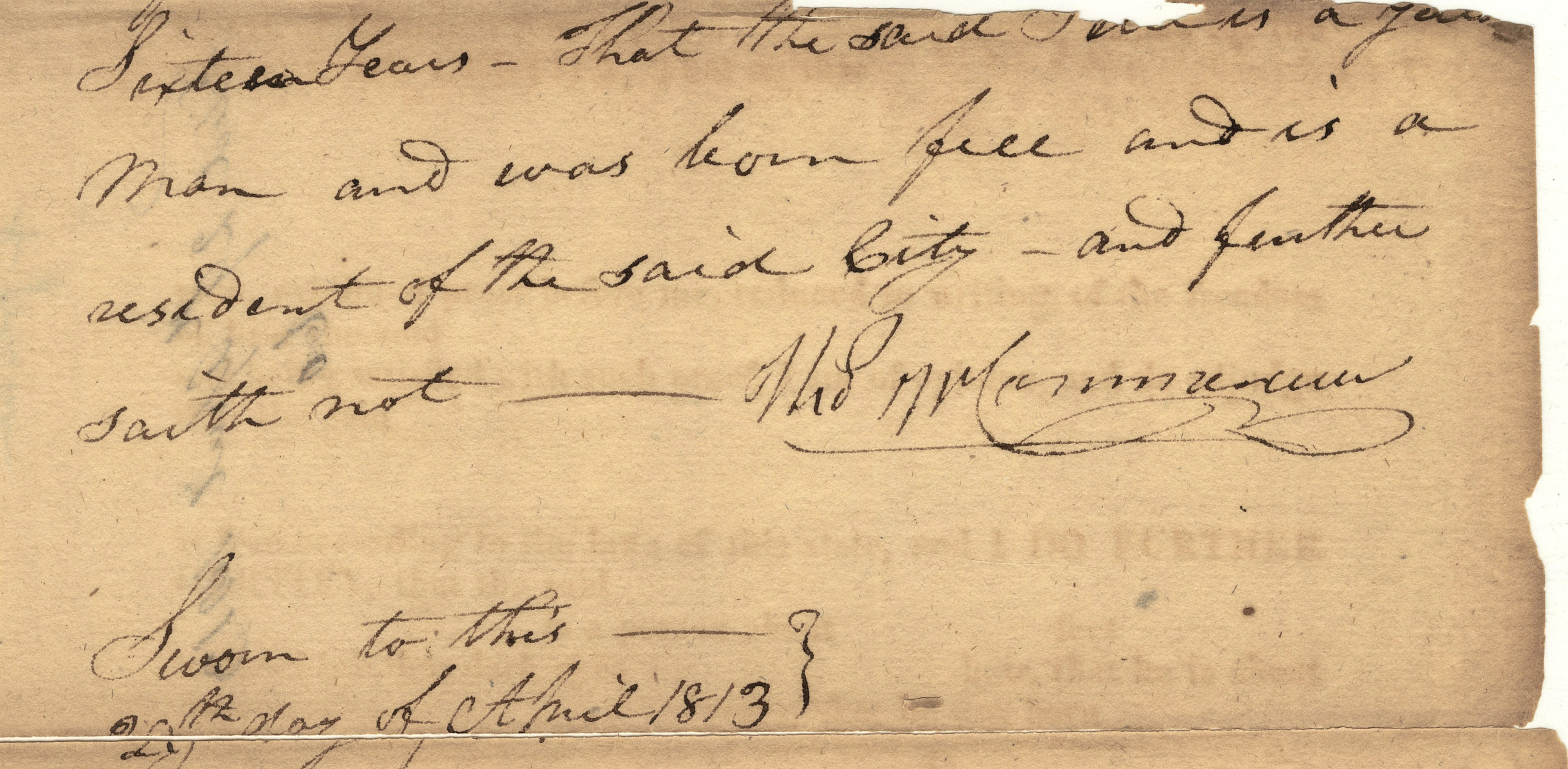

Installed in the museum’s Schafler Gallery, the presentation arrays 22 jars and jugs produced by the Commeraw shop between the late 1790s and 1819, showing them alongside another 14 pots by competitors such as David Morgan (active circa 1795-1803), Clarkson Crolius Sr (1773-1843) and John Remmey III (1765-after 1831). While no likeness of Commeraw survives, Crolius is depicted as the gentlemanly speaker of the New York State Assembly in an 1825 portrait by Ezra Ames (1768-1836). The curatorial team dug deep into the institution’s renowned archives to provide further context in the form of contemporaneous letters and documents. Of special note is the only known example of Commeraw’s signature, inscribed on an 1813 certificate of freedom for Peter Johnson.

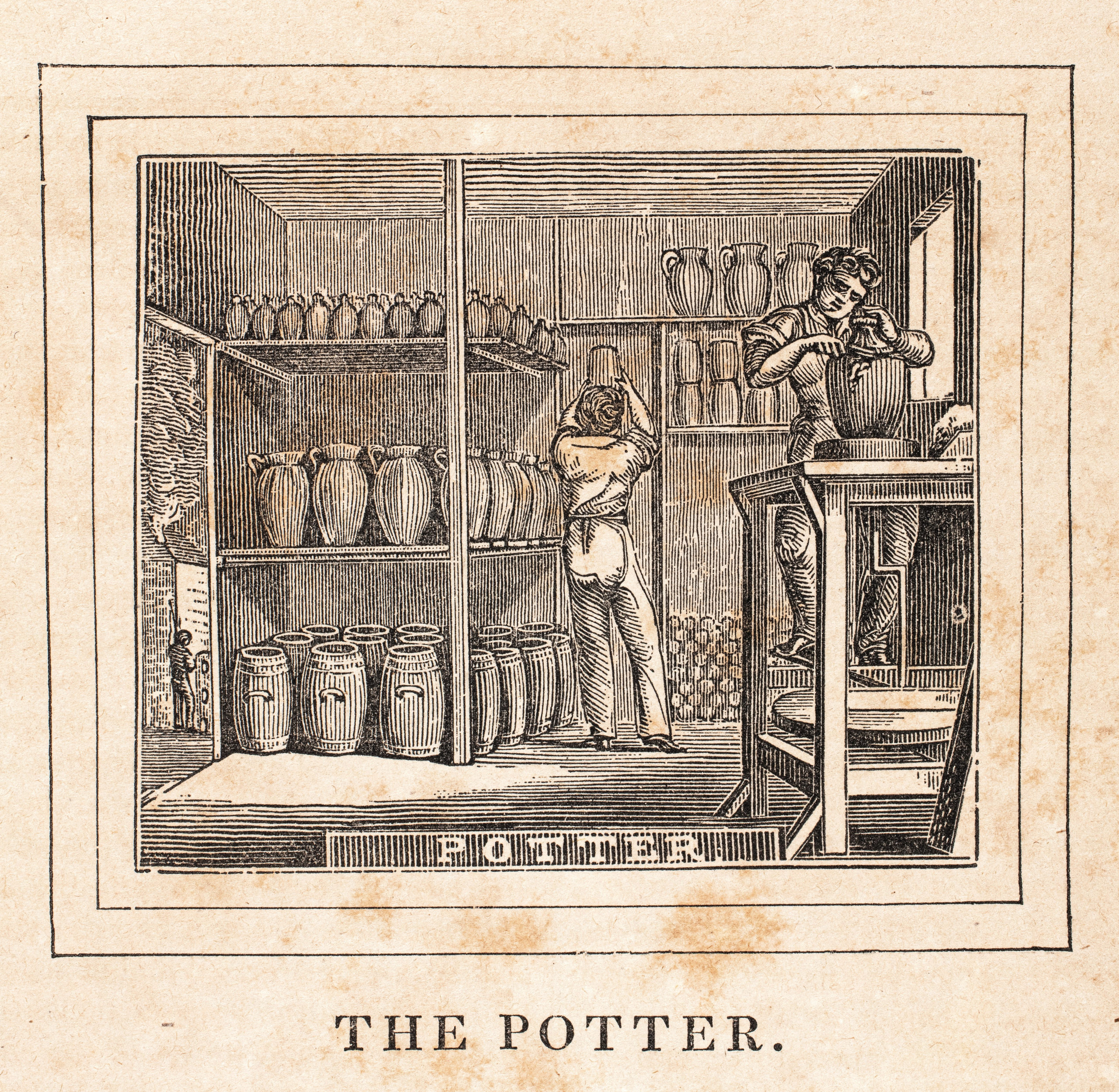

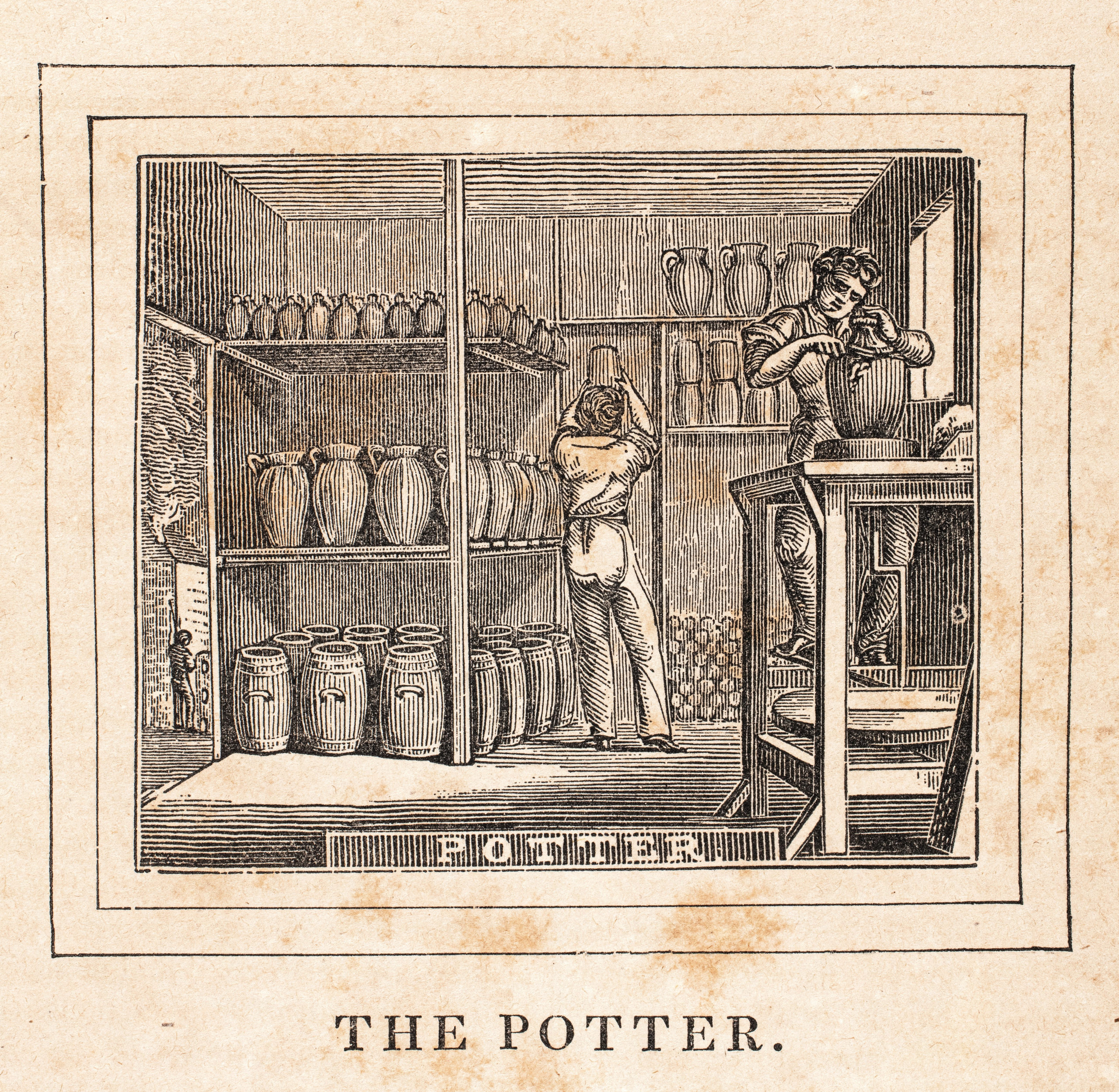

“The Potter,” from Edward Hazen, The Panorama of Professions and Trades, Philadelphia, 1837. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society. Most potters learned the trade through apprenticeship. Commeraw’s training would have encompassed all aspects of the business, from identifying and procuring suitable clay, to throwing, firing, glazing, decorating and marketing wares.

On a walk through the museum’s laboratories, where conservators readied pieces for display, Hofer spotted a favorite Commeraw jug. “Collectors would call it a ‘five-line’ pot,” the N-YHS vice president and museum director said of the extensively inscribed and cobalt-decorated vessel, acquired from sculptor and folk-art collector Elie Nadelman in 1937.

“I was one of many museum professionals and collectors who previously believed Commeraw was a white potter of European descent,” notes Hofer, who with colleague Robinson explores the triumphs and missteps of early researchers and traces the history of collecting Commeraw pottery over the past 130 years in an essay for Ceramics in America (CiA). They write that it was curator Carolyn Scoon (1903-1976) and dealers Katharine Willis (circa 1875-1956) and Helen McKearin (1898-1988) who recovered Commeraw’s name and working dates.

Borrowed for the display is the first Commeraw pot publicly exhibited. Drawn from the Grolier Club’s popular Dutch Kitchen of 1895, the 13-inch-tall jar is marked “Commeraw’s Stoneware” with a backwards “S” and “N,” an idiosyncratic feature of the potter’s work.

“Crafting Freedom” arrays exceptional examples from top collections, foremost among them a 3-gallon jug of circa 1800. Auctioned by Crocker Farm in 2021 for $96,000, the standing auction record for Commeraw, and now in the collection of Joseph P. Gromacki, the 15-inch-tall work is admired for its graceful ovoid shape, refined color, even glazing and robust cobalt-blue decoration. The latter consists of the artist’s stamped brand plus two rows of alternating tassels and crescents, or “swags,” stamped tip to tip to create Commeraw’s distinctive “clamshell” or “bowknot” designs.

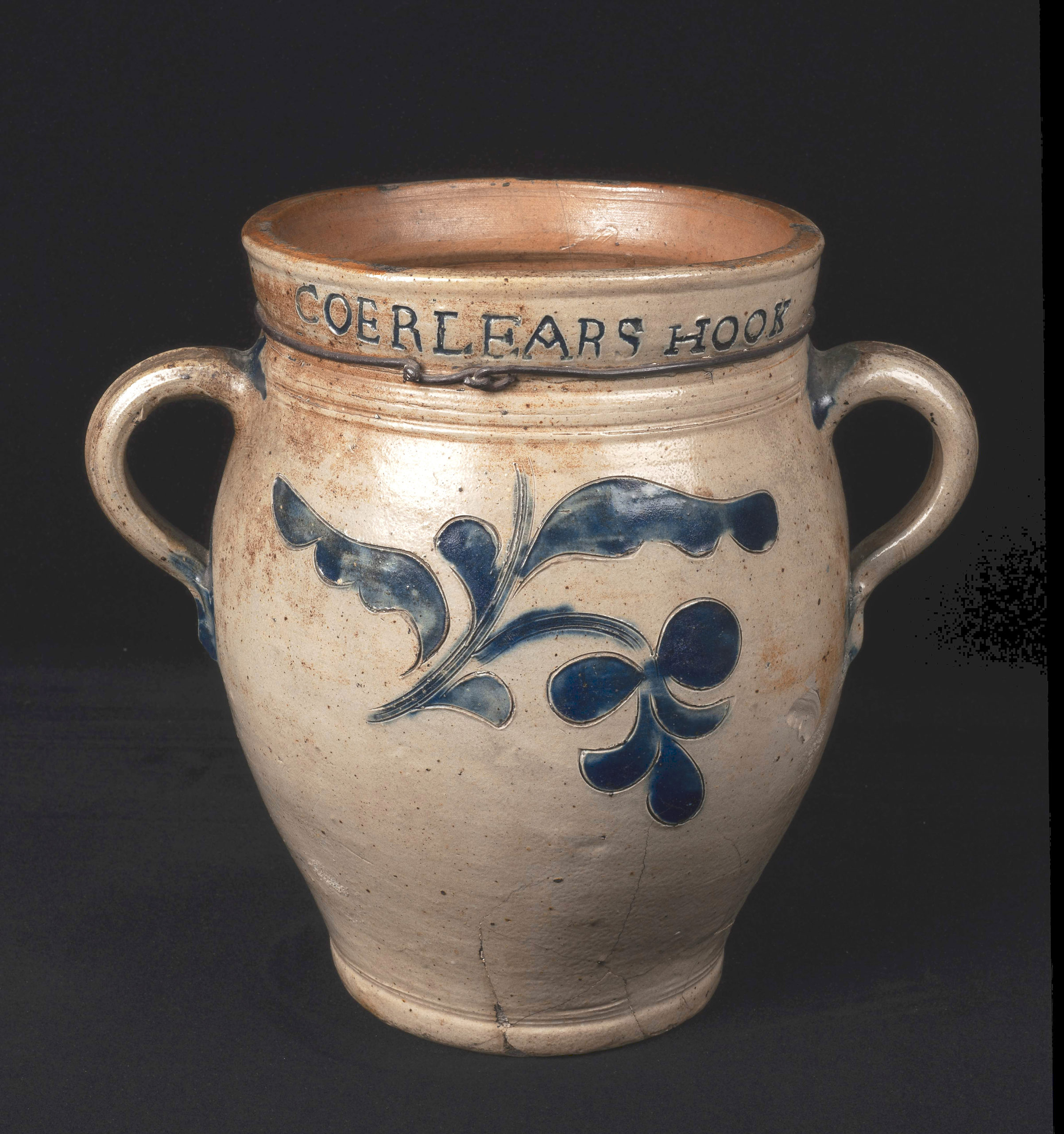

Jar by Thomas W. Commeraw, circa 1797-1800. Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, N.Y.; gift of J. Holman Swinney. N0070.1989. Richard Walker photo. The earliest pots that survive from Commeraw’s pottery at Corlears Hook, along the East River, bear floral motifs incised freehand with a stylus. These wares are among the first New York City stoneware vessels marked with a place name.

Delightfully, the show foregrounds New York’s lively oystering industry. Featured are chunky, cylindrical oyster jars, made of stoneware circa 1800-05 by Commeraw and impressed with the names of merchants such as Daniel Johnson and George White. These early advertising pieces, once mainly traded among bottle collectors, were shipped far afield and have surfaced as distantly as Guyana. N-YHS adds further context with a circa 1840 jar for pickled oysters made for Downing’s Oyster House, owned by abolitionist and entrepreneur Thomas Downing.

“The Potter’s Shop” offers a comparative view of the New York market. An 1809 Crolius price list notes pots ranging in size from one pint to four gallons, in “strait” or “bellied” shapes. Two subsequent sections confront civil rights issues encountered by Black New Yorkers and contemplate the activism of Commeraw and contemporaries such as church leader and tobacconist Peter Williams Jr.

Some of the most compelling documents are found in “To Stay or Go.” They offer insight into Commeraw’s decision to join the ACS mission to Africa and provide a lively account of his experience while there. Not to be missed is an 1821 letter from Commeraw’s New York pastor to Peter A. Jay describing the potter’s motive: “He got in his head…that he was going to Africa to be a great man and nothing would dissuade him.”

In lieu of a catalog, the N-YHS is collaborating with Chipstone Foundation on a collection of essays, which will appear online and in the 2024 print edition of CiA. Co-curator Shapiro, whose fascination with Thomas Commeraw deepened during a 2018-19 resident fellowship at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, marshalled the effort.

Detail, Certificate of Freedom for Peter Johnson, 1813, signed by Thomas Commeraw. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society. In 1811, the New York State legislature passed a law to suppress Black voters, requiring them to pay a fee and file a Certificate of Freedom, including a sworn statement from a third party attesting to the voter’s free status and residency.

“I always envisioned this project bringing together a diversity of disciplines and voices,” says the Massachusetts-based expert, who compiled the findings of archaeologists and historians, among them co-curators Hofer and Robinson; Leslie M. Harris, a scholarly advisor to the exhibition; Meta Janowitz; Tiffany Momon; Michael Lucas; Jessica Striebel MacLean; Kurt Russ; and collector and marine biologist Christopher Pickerell. Zipp contributed an essay on Commeraw’s earliest work — never stamped with his name, only “Coerlears Hook” — and how its authorship, like Commeraw’s own identity, was lost to history.

When we spoke, Shapiro was anticipating an upcoming engagement with Queens, N.Y.,–based educator, activist and ceramist Sana Musasama (b 1957), who in response to Commeraw’s life and work created the glazed-stoneware sculpture group “Passage,” visible to visitors as they enter the museum. “It’s important to show that Commeraw’s work resonates in the present,” he explained.

If “Crafting Freedom: The Life and Legacy of Free Black Potter Thomas W. Commeraw” exposes some of the biases of early scholars, it also demonstrates their keen perception of quality. Marvels of research more than a century in the making, book, show and journal prove that the best will out. As Hofer and Robinson write, “…were it not for Commeraw’s material legacy — the sturdy, boldly marked and exuberantly decorated stoneware vessels — his story would have likely remained lost to history.”

Oyster jars made for Daniel Johnson and George White, attributed to Thomas W. Commeraw, circa 1800-05. Collection of Christopher Pickerell. Andrea Pickerell photo. Commeraw expanded his business by forging connections with local Black oystermen, who dominated the city’s oyster trade.

Following its close in New York City, “Crafting Freedom: The Life and Legacy of Free Black Potter Thomas W. Commeraw” will travel to the Fenimore Art Museum, where it will be on view from June 24-September 24.

To purchase Commeraw’s Stoneware: The Life and Work of the First African-American Pottery Owner by A. Brandt Zipp, go to www.crockerfarm.com/store or call 410-472-2016.

The New-York Historical Society is at 170 Central Park West at 77th Street. For more information, 212-873-3400 or www.nyhistory.org.

Images are courtesy of the New-York Historical Society unless otherwise noted.