Installation view, “Her Brush: Japanese Women Artists From The Fong-Johnstone Collection,” on view at the Denver Art Museum through May 13.

By Karla K. Albertson

DENVER, COLO. — Although open since November, “Her Brush: Japanese Women Artists from the Fong-Johnstone Collection” is an exhibition that keeps on giving, both to those who can travel to the architecturally adventurous Denver Art Museum with its 2006 “flying” wing designed by Daniel Libeskind and to those who will study the scholarly research the show’s subject has inspired. In a companion guide for the exhibition available on the museum’s website, readers can delve deeper into the source of the exhibits in the “Introduction to the Fong-Johnstone Collection and Study Collection” by Dr Einor Keinan Cervone, associate curator of Asian art.

Cervone co-curated the show with Professor Andrew L. Maske, a specialist in Japanese ceramics who teaches museum studies at Wayne State University. He had been working toward this exhibition since 2018 when Dr John Fong and Dr Colin Johnstone pledged their collection of more than 500 works of art to the Denver Art Museum. The gift was especially strong in examples by women artists working from the 1600s to the 1900s. The collectors had collaborated with Chinese art dealer Alice Boney (1901-1988). In addition to the show and a coming catalog, the material will be available to scholars for study in the future, both in person and online.

Cervone spoke with Antiques and The Arts Weekly: “When I joined in September 2021, I worked with Andrew Maske and Patricia Fister, who is really the progenitor of the subject.” Fister organized the exhibition ‘Japanese Women Artists: 1600-1900’ in 1988 and copies of that catalog are still available along with many other related works by the author. She also contributed an online essay and companion resource on the museum’s website: ‘Calligraphy, Poems, and Paintings by Japanese Buddhist Nuns.’”

The curator continued: “What we’re hoping to achieve is that viewers will make a personal connection with the artists and their journeys. To understand the challenges that they faced but also to appreciate the incredible art they were able to produce. They were phenomenal artists and they were quite well-known in their own time. We are able to activate this huge gift that we received and to reintroduce a lot of these artists and their place in art history. And we’ve structured the exhibition to show how they used the medium of art in their lives as women.” She referred to the art works as time travel machines, in a way — the importance of putting a brush to paper gave them a chance of immortality through their art.

The exhibition’s presentation is divided into seven sections. Although women may not have had the freedom of that bearded sage with a brush that has become the standard image of an ancient Chinese artist, there were, in fact, a number of avenues the artistically inspired could escape down. One was “Taking the Tonsure” or joining a Buddhist monastery, the subject Fister treated in the essay cited above.

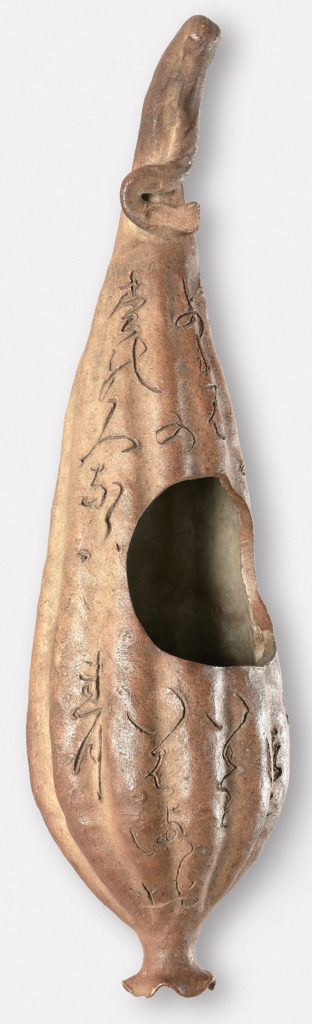

“Hanging Flower Vase in Shape of Hechima Gourd (hana ike)” by Ōtagaki Rengetsu, 1791-1875, stoneware. Denver Art Museum: Gift of Drs John Fong and Colin Johnstone. Photo ©Denver Art Museum.

Of course, there were rules, prayers and services to perform — but the nuns had more freedom than in a life obeying the commands of father, husband and son. Just as in the West, women in wealthy or noble families had times of leisure when they could pursue artistic pastimes. As young women, they could study “The Three Perfections” — painting, poetry and calligraphy — as long as there was no commercial goal.

Freedom could also be found in artistic circles, rebelling with other intellectuals. And if a woman was in the “entertainment business” — anything from actress to courtesan — there was liberty only limited by the need to pay the bills.

A favorite work in the exhibition is in the concluding section — “Unstoppable (No Barriers)” — an ever sought-after goal taken from a screen by Murase Myodo (1924-2013). Her double-sided screen has characters on one side for “no” or “nothingness”; on the other for “barriers.”

In another subtle shattering of the glass ceiling, Otagaki Rengetsu writes in a poem:

“Taking up the brush

Just for the joy of it,

Writing on and on, leaving behind

Long lines of dancing letters.”

“Autumn Landscape” by Kō (Ōshima) Raikin, late 1700s, hanging scroll; ink on paper. Denver Art Museum: Gift of Drs John Fong and Colin Johnstone. Photo ©Denver Art Museum.

As noted above, “Her Brush” has much more to come. Cervone noted that this was a different sort of project in an altered cultural landscape with new technologies at their disposal: “There will be a catalog coming out on February 25. We’re producing a digital catalog that’s also available as print on demand. So, it will have an eternal life online — open source, available free of charge to anyone who seeks to use it. And it will also be available to be downloadable as a print PDF.” [This is possible using a platform named Quire, developed by the Getty (quire.getty.edu).]

The catalog will appear on February 25, which is the date of an international symposium focused on the subject of the exhibition from 9 am to 4 pm at the museum. Cervone said: “We’re bringing scholars from all backgrounds — curators, art historians, gender studies specialists, historians, connoisseurs — with information to bear on this subject.

Summing up, the curator wrote in her online essay: “In short, ‘Her Brush’ is both a promise and an invitation. It is the museum’s commitment to advancing the field through this collection. And it is an invitation to you — whether you are a student, an educator, a specialist or simply curious — to explore, contribute, engage and to make this art your own.”

“Her Brush: Japanese Women Artists from the Fong-Johnstone Collection” will remain on view at the Denver Art Museum through May 13.

The international symposium on February 25 is free, registration is required: (www.denverartmuseum.org/en/calendar/her-brush-new-approaches-gender-and-agency-japanese-art

Denver Art Museum is at 100 West 14th Avenue. For information, essays, images and activities for children, 720-865-5000 or www.denverartmuseum.org.