Beadwork basket with a courting couple in a garden and the Four Seasons, dated 1662, height 3½ inches. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art (1988.26). The fact that this basket is dated “1662” — the year in which Charles II married Catherine of Braganza — no doubt appealed to Griffiths’ Royalist loyalties to the House of Stuart. Even so, the figures more likely represent the maker, whose initials were presumably “M W,” and her betrothed.

By Laura Beach

NEW HAVEN AND LONDON – Robert Wemyss Symonds (1889-1958) was already an acclaimed expert on English furniture when he published the first of 20 articles in the nascent Magazine Antiques in June 1923. By the time he died 35 years later, the English architect, advisor and author had to his name 15 books and more than 466 articles, many in The Antique Collector, Apollo, The Connoisseur, Burlington Magazine and Country Life. As decorative arts authority Christian Jussel observes in English Furniture 1680-1760, one of two volumes comprising The Percival D. Griffiths Collection, the monumental new study from Yale University Press, “Symonds’s writings permeated every book published on English furniture and dominated the field of English furniture collecting; indeed, they are still important more than 60 years later.”

How Symonds became a leading antiquarian and lasting influence is just one facet of a story masterfully told by Jussel and co-author William DeGregorio, an independent scholar in historic textiles and costumes who wrote the book’s second volume, English Needlework 1600-1740. As Jussel and DeGregorio reveal in their exhaustively researched work, compiled with the assistance of Dru Muskovin, Symonds’ fame in part grew from his role advising one of the early Twentieth Century’s foremost collectors, Percival D. Griffiths (1861-1937), whose holdings of early English furniture and domestic needlework were unsurpassed.

The Percival D. Griffiths Collection is the latest in a spate of recent studies on the history of collecting. At the heart of the discipline is the recognition that, while collecting can be an individual and highly competitive pursuit, it is also by definition social and communal, its parameters largely defined by received wisdom and shared taste. By analogy, The Percival D. Griffiths Collection is a fitting tribute to the collector who commissioned the research, the late John H. Bryan Jr (1936-2018), and an elegant frame for today’s collecting milieu. Jussel is a retired dealer associated with a dynastic family firm, Vernay & Jussel, Inc.; DeGregorio’s affiliations include the storied purveyor, Cora Ginsburg LLC.

A prominent philanthropist who served as Sara Lee Corporation’s chief executive officer from 1975 to 2000, Bryan Jr began collecting in the 1960s. In the spirit of Griffiths and his inexact American counterpart Irwin Untermyer (1886-1973), Bryan Jr, assembled exemplary collections of English furniture and needlework, which he enjoyed at his estate, Crab Tree Farm on the shores of Lake Michigan. In 2013, Bryan Jr engaged Jussel and DeGregorio to undertake a study of Griffiths. It was Jussel who in 2017 acquired on Bryan’s behalf what had been a star of both the Griffiths and Untermyer collections, the 1738 walnut and parcel-gilt desk-and-bookcase made by London cabinetmaker John Unwin for Quaker merchant Caleb Dickenson.

Christian Jussel and William DeGregorio with Scarlet on a recent afternoon in Connecticut. At the prompting of the late collector and philanthropist John Bryan Jr, and with the assistance of Dru Muskovin, the authors researched and wrote the two-volume book, The Percival D. Griffiths Collection: English Furniture 1680-1760 and English Needlework 1600–1740.

Jussel and DeGregorio painstakingly reconstructed the Griffiths collection by cross-referencing period photographs of the interiors at Sandridgebury, Griffiths’ estate in Hertfordshire, with exhibition and auction catalogs, museum records, period literature illustrated with Griffiths’ holdings and assorted other archival materials. They drew from Symonds’ papers at Winterthur Museum and scoured a photographs album, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in which Griffiths recorded much of his needlework collection from 1927 to 1937. Their hunt resulted in an 864-page book with 667 catalog entries, the latter representing a portion of what the Englishman once owned. “Every piece for which a photograph could be found is included, and we have attempted to trace the ownership, exhibition and publication history of each one,” they write. Outside the book’s scope are Griffiths’ lesser collecting interests, among them silver, Chinese ceramics, book bindings and objets d’art.

Griffiths, an accountant, was born in London but made his first professional mark during a stint in the United States representing the firm Deloitte. In 1900, Griffiths and his American-born wife leased Sandridgebury near St Albans, about 25 north of London, to use as a seasonal retreat, residing in London between November and July. An avid sportsman, Griffiths died in 1937 when he fell from his horse while hunting with the Whaddon Chase. Christie’s auctioned what remained of his collection in 1939.

The son of a portrait artist and nephew of a Royal Academician, Symonds – a working architect who for a time maintained a practice with Robert Lutyens, son of the famous architect – made a name for himself in antiques while still young. Furniture historian Adam Bowett writes that Symonds’ first two books, The Present State of Old English Furniture (1921) – which included 53 pieces from Griffiths’ collection, plus another two subsequently purchased by the collector – and Old English Walnut and Lacquer Furniture (1923) transformed the study of English furniture. Symonds was held in deservedly high esteem as an expert, says Jussel, noting, “Anyone who has acquired a great number of pieces and assembled a serious collection will have made occasional mistakes. But in Symonds’s case, they were few…”.

Symonds judged furniture on the basis of its color and surface condition; design, proportion and ornamentation; and quality of its workmanship. His third book, English Furniture from Charles II to George II (1929), remained a standard reference well into the Twentieth Century. The expert was fastidious about patina, in part because he believed understanding surface armed one against trickery, and was the first, says Jussel, to write about modern fakes, a subject to which he often returned in print and in at least two exhibitions.

Cabinet with allegorical female figures, dated 1657, height 9-13/16 inches. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Elizabeth Day McCormick Collection (43.524). Griffiths was especially fond of embroidered cabinets, or “caskets,” as they are also known. This “double casket” features a top compartment for small bottles of perfume or ink. The body of the box contains silk-lined compartments for writing implements.

Griffiths began collecting “old furniture” around 1900. Like many an inexperienced collector, he was duped, initially buying heavily carved mahogany furniture in the Chippendale style that was not as represented. In one oft-repeated tale, Griffiths recalled spotting in a London shop window a table identical to one he already owned. When he inquired within, the oblivious merchant boasted that he had made “a large number of such pieces of Chippendale for an old buffer who lives at St Albans!”

Griffiths met Symonds in 1911. They worked together for the next 26 years, Griffiths assiduously trading up to acquire better examples for a collection that ran from Charles II to George II examples and was especially strong in walnut and walnut-veneered pieces. “It defined the parameters of many mid-Twentieth-Century English furniture collections,” Bowett writes. “There was nothing showy, vulgar or de trop; it epitomized the English style – informal, gentlemanly and effortlessly well mannered.”

Symonds was little involved in Griffiths’ needlework collection, as formidable as his furniture holdings. DeGregorio speculates on the role played by dealer Frank Partridge, whose papers survive but were not accessible to the researchers. In the absence of inventory records, little provenance is known. What is certain is that Griffiths began collecting Tudor and Stuart needlework around 1910 and that he bought widely. By 1913 he had amassed a large needlework collection, at its peak around 1926.

Much of Griffiths’ furniture and some of his needlework changed hands privately before the posthumous auction of his estate. Representatives of both the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Victoria & Albert Museum were interested, but neither institution acted with sufficient speed or resolve to acquire major portions of the collection. Treasured works – both furniture and needlework, some given by Untermyer in 1964 – did later end up at the Met, where, even after some subsequent deaccessioning, they still form the largest group of Griffiths objects in a public institution.

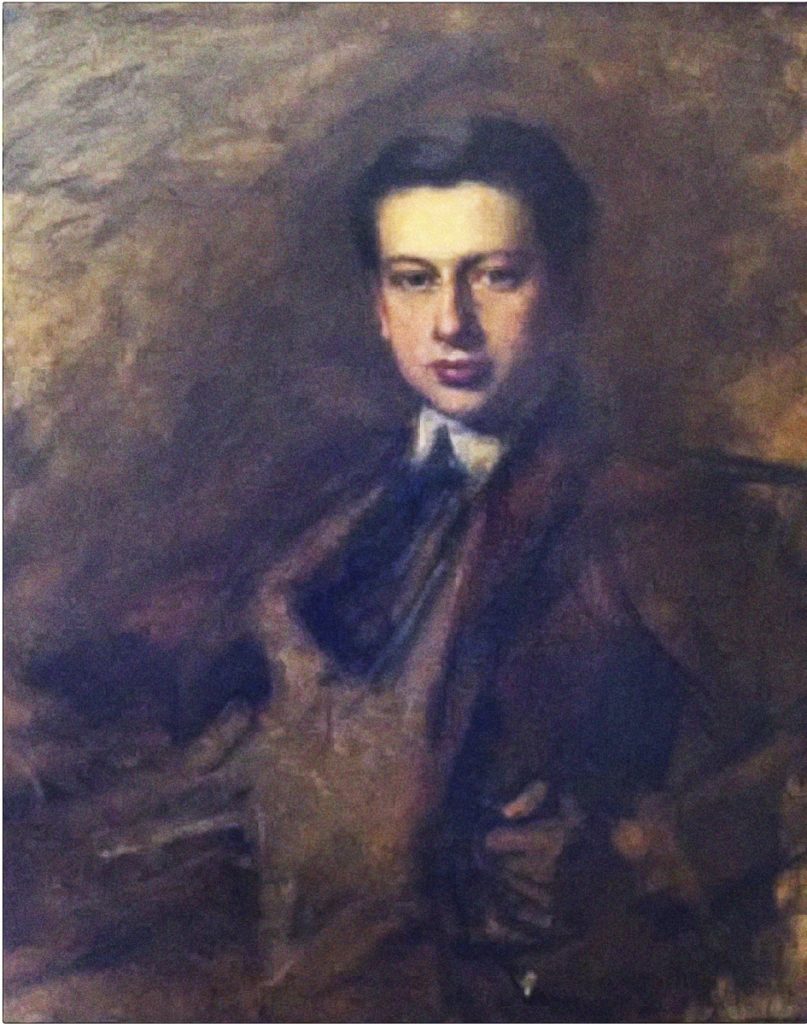

This portrait of Robert W. Symonds by an unknown artist shows the author, expert and advisor as a young man, probably at about the age when he first met Griffiths in 1911. Oil on canvas. Private collection.

DeGregorio documents in detail the growing interest in historic English domestic needlework, from the first flickering of public interest in the late Nineteenth Century to 1929, by which time, he writes, “The fashion for Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century English embroidery was firmly entrenched even in America.”

Particularly interesting is the scholar’s analysis of the growing market for embroidered caskets – cabinets, in modern parlance – and beadwork baskets, both quintessential collecting trophies in our time but largely overlooked before Griffiths, who owned more than 15 baskets and was delighted to acquire a dated 1662 casket depicting the story of Esther in 1911. The Minneapolis Institute of Art today owns the latter.

Stressing that Griffiths was not the first or only private collector to be interested in domestic needlework, DeGregorio sets the scene for future scholars by penning extensive profiles of Griffiths’ British contemporaries, among them William Hesketh Lever and the husband-and-wife duo Percy and Theresa Macquoid. He also assesses Griffiths’ lingering influence on institutions such as Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, where the Griffiths provenance attaches to needlework from the estate of Mrs DeWitt Clinton Cohen, acquired by the Foundation through Cora Ginsburg.

Symonds, who outlived Griffiths by 21 years, also exerted significant and lasting influence in the United States. Jussel recounts the advisor’s work with Francis P. Garvan (1875-1937) who, though thought of as an Americanist, lived with, and bought on Symonds’s advice, English antiques for his apartment at 740 Park Avenue. Symonds also figures in different chapters of Colonial Williamsburg’s history. The Foundation’s chief architect, William Perry, ignored a 1929 suggestion that Symonds be hired as a furniture consultant. Three decades later, however, curator John Graham commissioned Symonds to write a book on English furniture at Colonial Williamsburg, a project cut short by Symonds’ death.

Walnut and parcel-gilt desk and bookcase by John Unwin (b 1695), 1738, height 84 inches. Bryan Collection. In 1923, Griffiths acquired this sumptuous case piece made for Quaker merchant Caleb Dickenson. Later owned by Judge Irwin Untermyer, who gave it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1964, it is now in the Bryan Collection.

Approximately 50 percent of the pieces shown in The Percival D. Griffiths Collection remain untraced, leaving open the possibility of more discoveries to come. Indeed, as they were going to press, the authors learned of two additional volumes, auctioned by Christie’s in 1979 but still unlocated, containing photographs of the collections at Sandridgebury.

Jussel and DeGregorio write, “With this survey, we have only begun to answer the question posed by Mr Bryan in 2013. But by presenting Percival D. Griffiths, his contemporaries and his objects to the world in this way, we hope to inspire further exploration of the man and the collector, and to encourage a broader conversation about the history of collecting, connoisseurship and the affective bonds between man and object.”

The Percival D. Griffiths Collection: English Furniture 1680-1760 and English Needlework 1600-1740 by Christian Jussel and William DeGregorio is published by Yale University Press. Catalog entries provide color images, exhibition histories, references and provenance. For information or to purchase, go to https://yalebooks.yale.edu. You can also purchase by phone by calling the press distributor Triliteral, at 800-405-1619.

.jpg)

.jpg)