Cup with Bacchic ritual scenes, Roman, late First Century BCE–early First Century CE, cameo glass, 4-1/8 by 6-15/16 by 4-3/16 inches. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Malibu, Calif. Digital image courtesy of Getty’s Open Content Program.

By James D. Balestrieri

SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS – When it comes to landscapes, there is a footnote in a book by British author Robert Macfarlane, called The Old Ways, that haunts me. I have referred to it more than once, though not in this publication, each time with the hope that I will come to an understanding that will allow the idea behind it to come to rest. The Old Ways is about nature and language, Macfarlane’s twin subjects, and passions, encompassing his argument that humanity is losing touch with the natural world – The Old Ways is a memoir of walks, walking, of feet and ground – and that one way to know this is to observe the rapid loss of the rich lexicon that human beings have created to describe it. This is the quote, from the bottom of page 255: “‘Landscape’ is a late Sixteenth Century (1598) anglicization of the Dutch word landschap, which had originally meant a ‘unit or tract of land,’ but which in the course of the 1500s had become so strongly associated with the Dutch school of landscape painting that at the point of its anglicization its primary meaning was ‘a painterly description of scenery’: it was not used to mean physical landscape until 1725.”

So, a “term of art” in legal, real estate language, evolves into a word that describes a “genre of art” which then, in turn, evolves again into a “view of nature,” that is, a way of looking at a slice of the world as it appears before us.

Property first, art second, “physical landscape” last. The order of things here seems, well, wild, even backwards.

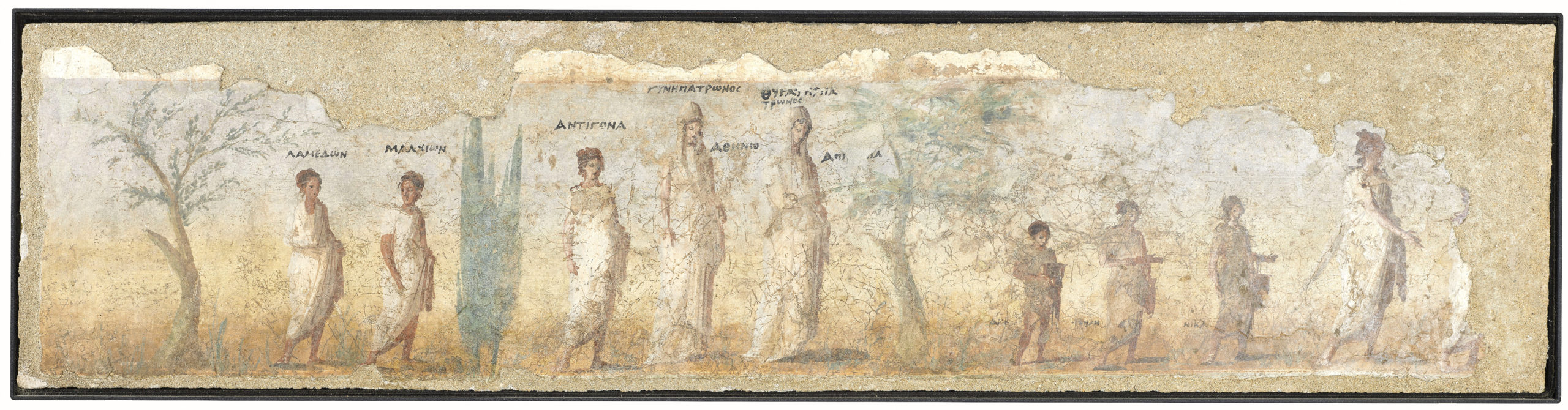

Wall painting with a procession to the tomb, from the Tomb of Patron, Rome, late First Century BCE, pigment on plaster, 16½ by 68-1/16 inches. Musée du

Louvre, Paris, Département des Antiquités grecques, étrusques et romaines. Stéphane Maréchalle photo ©RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NYC.

Looking at the works in “Roman Landscapes: Visions of Nature and Myth from Rome and Pompeii,” the first exhibition in the United States to explore landscape scenes as a genre of ancient Roman art, on view at the San Antonio Museum of Art through May 21, the order of definitions I described above begins to make at least some sense. Consider the Roman conception of deity and the supernatural world, an amalgam of belief systems that range from the Egyptian to the Etruscan to the Celtic gods of what is now England, and beyond, and ask this question: “Can nature, wrought into being by anthropomorphic gods and further shaped and reshaped by human beings to human ends, be said to be ‘natural’ at all in Western thought and art?”

Now consider the emergence of landscape in the First Century BCE in Rome as the exhibition presents it. As the civil wars of the late Republic gave way to the stability of the new empire under Augustus, and as Rome undertook a series of successful conquests that led to “elaborate triumphal processions in Rome [that] paraded foreign captives, animals and even landscapes that were recreated in illusionistic, three-dimensional models of mountains and rivers or shown in paintings with bird’s-eye views of battles and conquered regions.” Peace on land and sea allowed people to visit the “cities, sanctuaries and landmarks of myth that were now part of the Roman World.” Such bird’s-eye views “served the design of military campaigns and land surveys, and ultimately became a means for control.” (Bergman, cat. pp. 30-33) At the same time, an interest in “sacral-idyllic” ancient sites of ritual consecrated as much by time as by story, leads to what are perhaps some of the first visual representations of ruins. The exhibition is divided into five sections: “Garden Landscapes,” “Coastal Views,” “Cultivated Landscapes,” “The Dangerous Landscapes of Myth” and “Landscapes in the Tomb.” In none – as would come later, during the Renaissance – do any of these works exclude the presence of the human – and, if not the human, then the divine in human form.

“Garden Landscapes” represent nature transformed, tamed for human aesthetic pleasure. The “Coastal Views” are of magnificent seaside villas the architecture of which not only takes advantage of the landscape but reshapes it in order to do so. “Cultivated Landscapes” show abundance from land tamed for practical purposes. “The Dangerous Landscapes of Myth” focuses in particular on the story of Diana and Actaeon, in which Actaeon is transformed into a stag and torn to pieces by his own hounds after pursuing and seeing Diana, the goddess of the hunt, of the moon, of nature, as she bathes. Here our idea of the wild, of wilderness, becomes a metaphor having to do, not with transgressions against natural world, but of that world in its divine – which is to say, human – form. Lastly, “Landscapes in the Tomb” offers glimpses into the Roman notion of the afterlife, of Elysian fields, evergreen and teeming with life, outside the cycle of seasons, apart from nature’s harsh indifference.

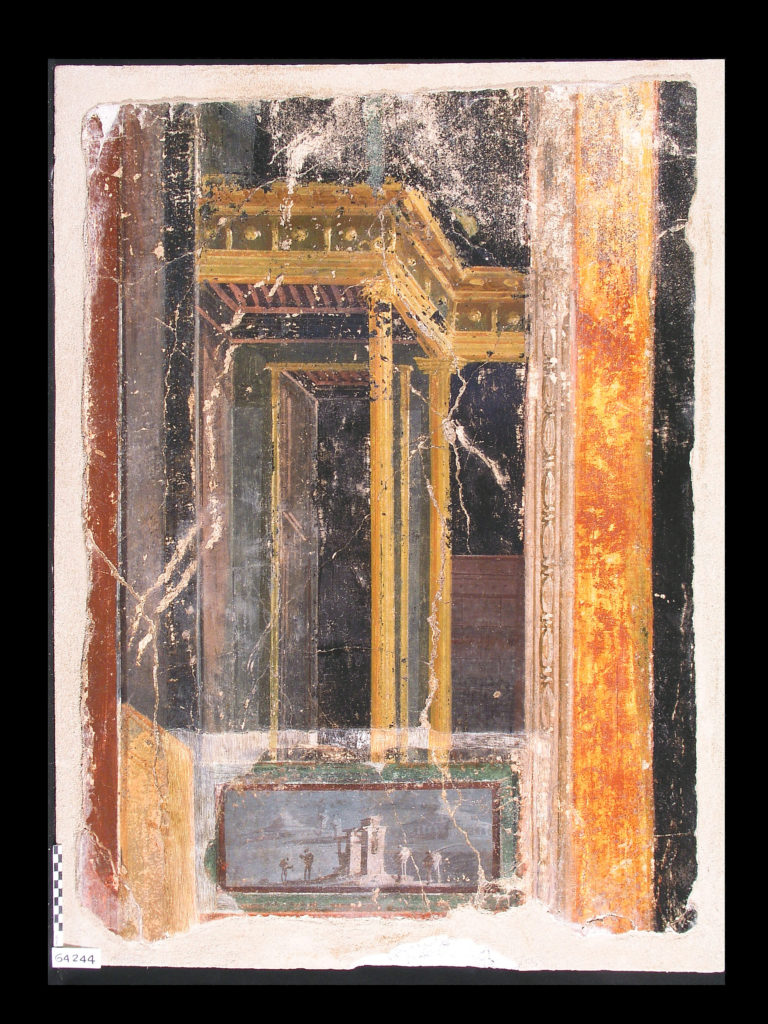

Wall painting with architectural elements and a landscape scene, from Villa Arianna, Stabiae, mid-First Century CE, pigment on plaster, 41 by 30½ inches. Parco Archeologico

di Pompei. By permission of the Ministero della Cultura – Parco Archeologico di Pompei.

Roman art has always suffered in the shadow of Classical Greece, of Athens and Phidias and all the rest. Philhellenism was very real. Wealthy educated Romans – whose lands encompassed Italy’s Magna Grecia and Greece itself – emulated their Hellenistic predecessors in political and artistic forms and it was stylish to do so. Roman copies of Greek originals in marble, for instance, are all we have to go on. Yet, in landscape at any rate – as well as in the still life – Roman painters and sculptors were inventive and even playful. And nothing like them, so far, has emerged in Greece.

We have to remember that we aren’t talking about painting in the way we think of it. The works in the exhibition range from cameos and glass carved-like cameos, silver, marble in relief and in the round, and fresco paintings, many of them sadly detached from their contexts in the villas and dwellings of Pompeii, Stabiae and elsewhere and hung in frames as if they were paintings. It might be better to think of the frescos in the exhibition as, simultaneously, paintings and architectural elements. They were intended to be – and to remain – on certain walls, juxtaposed with other fresco paintings, windows, doors, furnishings, sculptures. And, importantly, juxtaposed with the natural world without, with the views – the vistas from the villas, if you will.

Consider “Wall painting with a seaside villa, Stabiae,” a small fresco painted in the First Century CE. A bird’s-eye view of what must have been a splendid dwelling – thanks to the Roma discovery of hydraulic concrete – the villa thrusts out into the bay, utterly transforming the coastline and offering spectacular views from two floors of colonnades. Typically, on the walls of those colonnades, there would be frescoes such as this, and scenes of the views themselves, perhaps for guests who had the misfortune to visit on days when the sea fog was thick, or perhaps to exert a second, doubled kind of mastery over the landscape.

Wall painting with a seaside villa, Stabiae, mid-First Century CE, pigment on plaster, 11-13/16 by 19-11/16 inches. Parco Archeologico di Pompei.

A detail from “Wall painting with a landscape” scene, removed long ago from a villa outside Pompeii, depicts pilgrims approaching what seems to be a very old shrine, as the large tree growing from its base attests, while also linking the deity to nature. Tempting as it may be to view this fresco in the modern landscape tradition, as Verity Platt writes in her catalog essay: “there is no sense of the ‘sublime’ devoid of human habitation here.” (cat. p. 44) The tree – as well as other, presumably cultivated, trees beside the long villa below – is the only element that can be said to have grown “naturally.” Even the rock plateau that the sanctuary and shine sit on has a kind of regularity in its shape, as if it has been hewn.

The cameo and glass and silver cups featuring Bacchic scenes are friezes of a sort, rituals to the god of wine, wildness and generative power, who must be appeased in order that his untamed energy should be channeled into cultivation and the bounty of the earth. Yet little of the actual natural world, other than as places to hang offerings and ritual objects, suggests a wildness that requires taming. The possible political undertones in these works are worth considering: if Augustan Rome sought to project abundance, prosperity and peace, diminishing any disruptions, even from nature and the gods – this, even as Augustus and subsequent emperors assumed godhood themselves – might well make its way into the iconography of the visual culture. Venerate properly, these cups suggest, and the fate of Actaeon will not be yours.

Most striking of all, perhaps, in a quiet way, is the small “Relief with a herdsman and cow before a sanctuary.” The elements are all here: the gnarled tree growing through the gate to the sanctuary, the ruined wall that lets us see the shrine, topped with offerings of grapes, figs and other delicacies, the second shrine floating at top left in a perspective that, while it doesn’t quite work as perspective, is supremely effective at conveying the otherworldliness of the scene. Somehow, though, there’s more nature here, a sense of natural forces working on this place, entropy, time. The stone pinecone, executed in stone, atop the roof of the gate, will wear away, not as fast as the offerings in the basket, but one day, you feel, it will be no more. Same with the precarious shrine on rocks, floating in the air. That shrine on those rocks will crumble, vanish. All but ignored are the strange shallow disks precariously perched atop the sanctuary walls at left. Are these atavisms from Egyptian sun worship? Symbols of a forgotten faith? Why feel any of this? Simple. The herdsman and cow. They’re walking by, oblivious to this, as they are every day about this time, marking time in their own ritual of work and life that has nothing at all to do with the theological landscape. There’s just a glimpse of Bruegel’s “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus,” just a peek into and through and past the medieval, into a landscape we might call pastoral and see as more modern, one in which nature and time are constantly at work on all things and empires fall as surely as they rise.

Relief with a sanctuary and offerings, Roman, First Century CE, marble, 11-5/8 by 7-11/16 by 1-3/6 inches. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Classical Department Exchange Fund. Photograph ©2019 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Roman landscape gives us the first two of the three definitions of landscape, as derived from the Dutch word landschap: legal term of art and painterly description of scenery. At its best, it touches on that third and last definition, physical landscape. Hypothesis: until it became possible to imagine landscape without us, before us, even before our anthropomorphized gods, that third definition, physical landscape, was hard to imagine. Which is troubling in its irony. We speak of the Renaissance and Enlightenment as human-centered philosophical revolutions, yet, at precisely the same time, our notions of wilderness, and of nature and natural forces as something apart from us, unshaped and unshapable (which is not a word, but ought to be), also come into being.

The parsing and parceling of nature preceding the painting of nature; the painting of nature preceding the apprehension of nature as something we are both separate from and part of – all too human.

We have never stopped shaping nature. And nature has never stopped shaping us.

The San Antonio Museum of Art is at 200 West Jones Avenue. For information, 210-978-8100 or www.samuseum.org.