“Market Scene” by Jacob Lawrence, 1966, gouache on paper. Chrysler Museum of Art, Museum purchase 2018.22 © 2022 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

TOLEDO, OHIO — What does it mean for an African American artist to become associated with a postcolonial African art movement? And for that same artist to headline a major US exhibition of that community’s work in 2023? And what does it mean for visitors to perhaps be discovering all these artworks for the first time, a continent away from where they were produced? “Black Orpheus: Jacob Lawrence and the Mbari Club,” on view at the Toledo Museum of Art, June 3 through September 3, brings together the majority of Jacob Lawrence’s “Nigeria” series in a museum setting for the first time, while also spotlighting works from African artists who were leaders in the flourishing of postcolonial modernism in Nigeria and beyond. Discovery and rediscovery – and the complexities of both – are central themes of the show.

Lawrence has been much in the news lately. In 2020, the Peabody Essex Museum organized an exhibition of most of his “American Struggle” series, which later traveled to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In New York City, sharp-eyed visitors noted similarities to privately held paintings in their own orbit, right there in the city, and lugged them over to the museum to see if they were authentic. They were — and now two of the seven missing “American Struggle” paintings are accounted for. Something similar happened with “Black Orpheus,” says curator Kimberli Gant (formerly of the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, Va., which originated the show), with two Nigeria-based works on paper emerging just before and just after the Chrysler venue wrapped — both, unfortunately, too late to make it into the catalog, although the first did find its way onto the walls in Virginia.

It’s not unprecedented for important works to emerge from collectors who don’t know what they have, but why should this be seemingly the standard for Lawrence? His “Migration” series, first exhibited in 1941, had made him a star, and the Phillips Collection and Museum of Modern Art both eagerly bought half the 60-painting epic for their respective collections. Later series, including “American Struggle” and “Nigeria,” were also well received, but as this author wrote for Antiques and the Arts Weekly in 2020, the individual paintings were dispersed to different purchasers shortly after their completion. Separated from their companion works, the paintings lost their broader context and some of their pictorial and cultural power — sometimes even their association with Lawrence himself. It has been no easy task to reunite the Nigeria works, says Gant, who has been developing this project for a good six years. “It definitely was a bit of a jigsaw puzzle in terms of finding where things were.”

“Lamentation” by William H. Johnson (American, 1901–1970), circa 1944, oil on fiberboard. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Harmon Foundation.

There is a metaphor here for those inclined to see it. There is a quality to Black cultural production that relies on knowledge transfer — from parent to child, teacher to student, century to century and continent to continent. When that cord frays or is severed, there is labor involved in repairing it, and even if and when it can once again function as a conduit for creative knowledge, it is inalterably changed. This is the legacy of colonialism and the African diaspora — not to mention American chattel slavery, from which Lawrence’s family emerged — on Black artistic production.

Lawrence’s interest and travels to Nigeria were, in part, an effort to follow that cord back across the Atlantic, to the place his ancestors had called home. Through the New York City-based American Society of African Culture (AMSAC), Lawrence came to know artists affiliated with Nigeria’s Mbari Club and the journal Black Orpheus, both founded by Ulli Beier, a German scholar of African art and literature. (Both AMSAC and Black Orpheus were later discovered to have been funded in part by the CIA as part of a Cold War propaganda scheme). He sent works from the United States to be part of a group show in Nigeria, and, in 1962, he had a solo show at AMSAC’s headquarters in Lagos, which he traveled to Nigeria to close out. Once there, what he had perhaps initially regarded as simply an interesting exhibition and travel opportunity rapidly became a source of artistic and cultural inspiration.

Lawrence was particularly awestruck by the marketplaces, says Gant, which are the primary subjects of the series he completed mostly during a second, extended trip to Nigeria with his wife, Gwendolyn Knight, in 1964. “You see anything and everything” in the paintings, Gant says, including “the idea of being so communal and conversational as well. It’s not just about transaction.” Lawrence’s “Nigeria” paintings have all the color and drama of his earlier series while leaning even more heavily toward abstraction. “Lawrence writes that he really saw the world in pattern and shape and color, and so he really emphasizes that in the work,” says Gant. “There is an energy to a lot of that series that maybe you may not see in all the others. There’s a density in each of those works that’s really exciting.”

Cover of Black Orpheus Journal #2, January 1958

Jean Outland Chrysler Library, Chrysler Museum of Art

And yet his was no “starry-eyed” view of an African homeland, as Gant writes in the catalog for the exhibition. Lawrence wrote to his dealer, Edith Halpert, that the paintings he was producing in Nigeria were not “pretty” — indeed, poverty and violence are unabashedly on view — because “I can only paint what I feel and see around me.” He also noted that while he and Knight had “met many wonderful Nigerians” — including through the Mbari Clubs, which they frequented — they also experienced some hostility that he attributed to a general dislike for foreigners. Gant writes that the disappointing experience was shared by other Black Americans, including Langston Hughes, who traveled to Africa in part to rediscover their roots.

The wariness around Americans and Europeans is understandable, given that in the 1960s Nigeria — along with many other African nations — was emerging from a century and a half of colonial rule. It must have been challenging to see the influx of English-speaking artists and writers — including Lawrence, Hughes, William H. Johnson and others — as anything other than colonialism in another form (though scholar Leslie King-Hammond notes that Johnson was well received in Tunisia). Beier, to his credit, seems to have been much more concerned with providing a venue, in Africa, for African artists and writers than with bringing European cultural traditions to them. He founded Black Orpheus in 1957 specifically to provide a printed outlet for anglophone African creators along the lines of Alioune Diop’s French-language Présence Africaine, founded in 1947. Three years later, he founded the Mbari Club (the name derives from the Nigerian word for “creativity”) in Ibadan, and then it later spread to cities throughout Nigeria, providing a venue for exhibitions, workshops and networking for both artists and writers.

Ndubuisi Ezeluomba, Gant’s co-curator (formerly of the New Orleans Museum of Art, which was the second venue for the exhibition’s tour), writes in the catalog that both Black Orpheus and the Mbari club were central to the development of what is often termed “Nigerian modernism” or “postcolonial modernism.” The “Mbari movement,” he says, sought to redress some of the losses colonialism had wrought, wherein European traditions of literature and art were deemed superior, abstraction “primitive” (in a bad way), and traditional arts idolatrous.

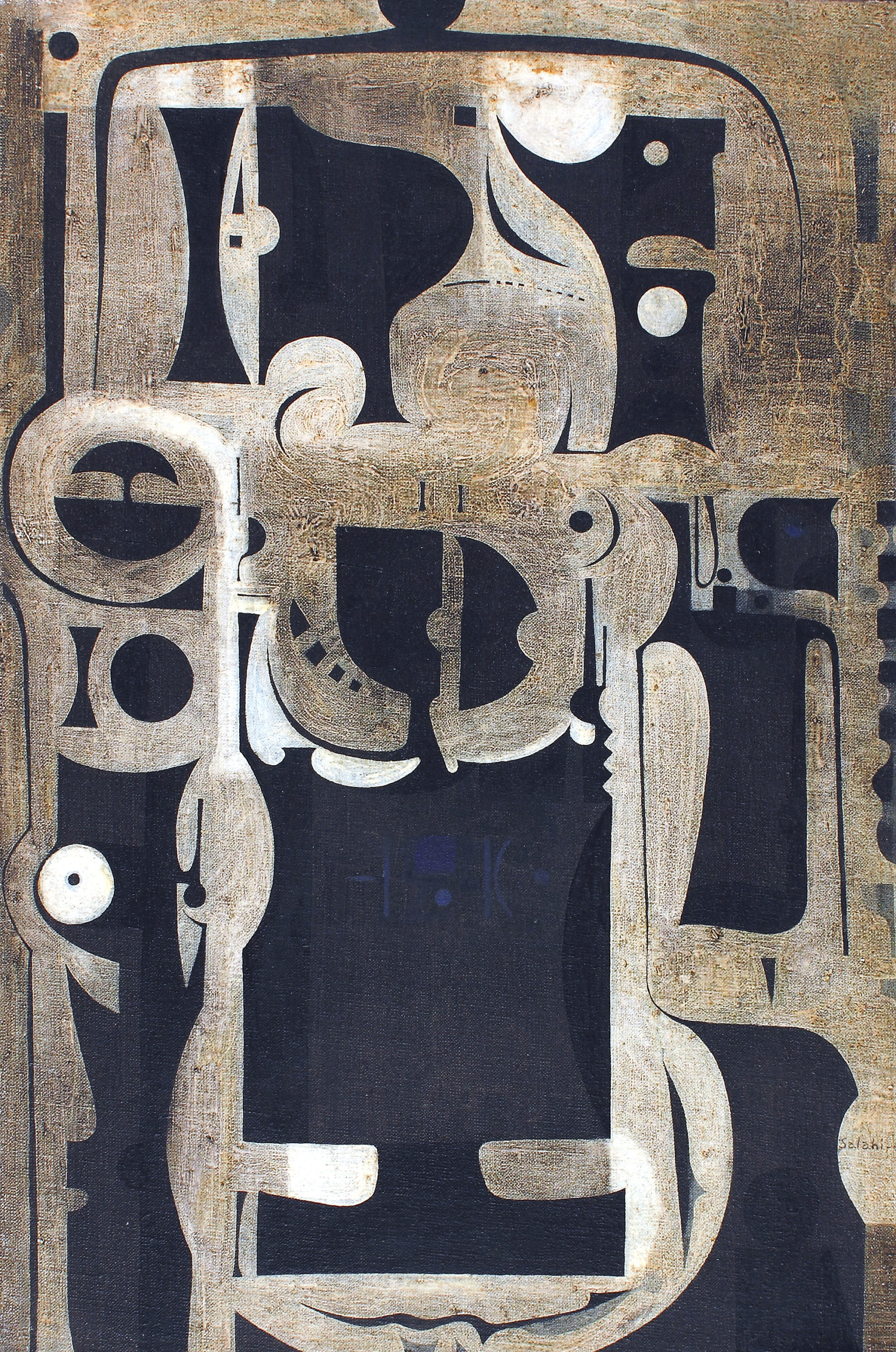

“They Always Appear #4” by Ibrahim El Salahi (Sudanese, b 1930), 1964-1965, oil on canvas.

Newark Museum of Art, Museum purchase 2014 Contemporary Art Society of Great Britain Fund © Ibrahim El-Salahi, courtesy Vigo Gallery. All rights reserved, ARS, NYC, 2022.

As an example, Gant notes, the Sudanese artist Ibraham El-Salahi, who had trained in France, had to “find a way to not alienate his community in Sudan, but he was still connected to Surrealism, to painting with oils and acrylics.” Ultimately, his lush, calligraphy-inspired abstractions embody “a unique point of view that is not shying away from his academic training but is embracing his cultural heritage.” El-Salahi was close to Ethiopian-Armenian artist Alexander “Skunder” Boghossian, who similarly created complex canvases that blend tradition and spirituality within a modern idiom. Artists like El-Salahi, Boghossian, and Nigerian native Uche Okeke, Gant says, rejected the idea of an artistic hierarchy with European traditions at the top. She describes their thought process: “We can utilize the western styles and traditions as we need to [in order] to augment the traditions and practices that are across Nigeria and across the African continent that we see as just as valuable.”

The locality of the Mbari clubs — they were all in Nigeria — might have limited the geographical scope of their activities, except that their publishing arm, which grew to encompass Black Orpheus, had a virtually unlimited reach. “Black Orpheus was really trying to promote primarily the African diaspora but also the global South,” Gant says. “The journal is really focused on these artists that are thinking about the blending of western and non-western traditions, and that’s not relegated to one part of the world.” She adds, “Because so many people were influenced by colonialism — the world is shifting at this moment; there is a lot of political and cultural diplomacy happening — this gives you a reminder of that.”

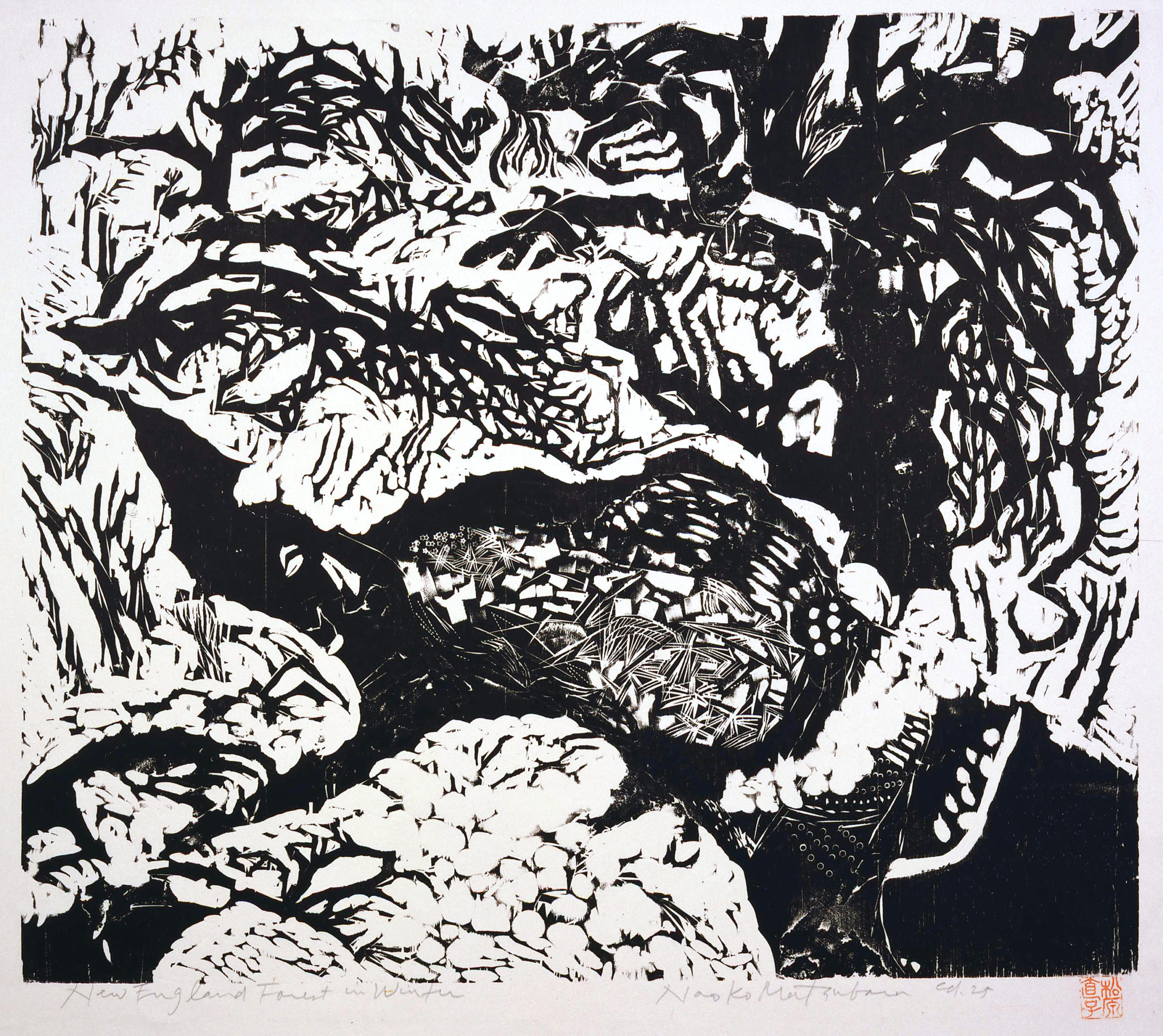

This is how Japanese Canadian artist Naoko Matsubara, for example, could come to be featured in the journal and have an exhibition of her woodcuts at the Oshogbo Mbari Club in 1965. In fact, women were a particularly strong presence in the Mbari movement, as discussed in the catalog. Austrian artist Susan Wenger did most of the Black Orpheus covers, nearly all of which are on display in the exhibition (Gant has also arranged to have high-resolution scans made of the journals to make them accessible for scholars). Beier’s wife, the British-born Georgina, organized and led workshops while developing her own artistic practice; she rejected the term “teacher” since it smacked of the kind of artistic hierarchy she’d left behind in Britain. And painter Colette Omogbai, born in Nigeria, went on to have a stellar international career after getting an early start at the Mbari Club in Idaban.

“New England Forest in Winter” by Naoko Matsubara (Japanese, b 1937), circa 1967, woodcut on paper. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of the Society of American Graphic Artists for the Benton Spruance Memorial Collection, 1969.

These are, for the most part, not familiar names to US audiences; most will be discovering them, so to speak, for the first time in the context of this exhibition. It bears noting, however, that just like Lawrence’s “lost” paintings, it’s less a process of discovery than long-delayed acknowledgment — they have been there all along. Gant is straightforward about her hope that the show will help to mend some of the connections severed through the legacy of colonialism and the African diaspora. “I want the names of artists in this exhibition to become as household ones as any of the artists we see in a Jansen’s art history book,” she says. “So, when I say ‘Hey, why don’t you do a dissertation on Uche Okeke?’ that’s a name that they just know as if I said Pablo Picasso. The works are different but no less powerful and important, and they need to be recognized and known.”

The Toledo Museum of Art is at 2445 Monroe Avenue. For information, 800-644-6862 or www.toledomuseum.org.