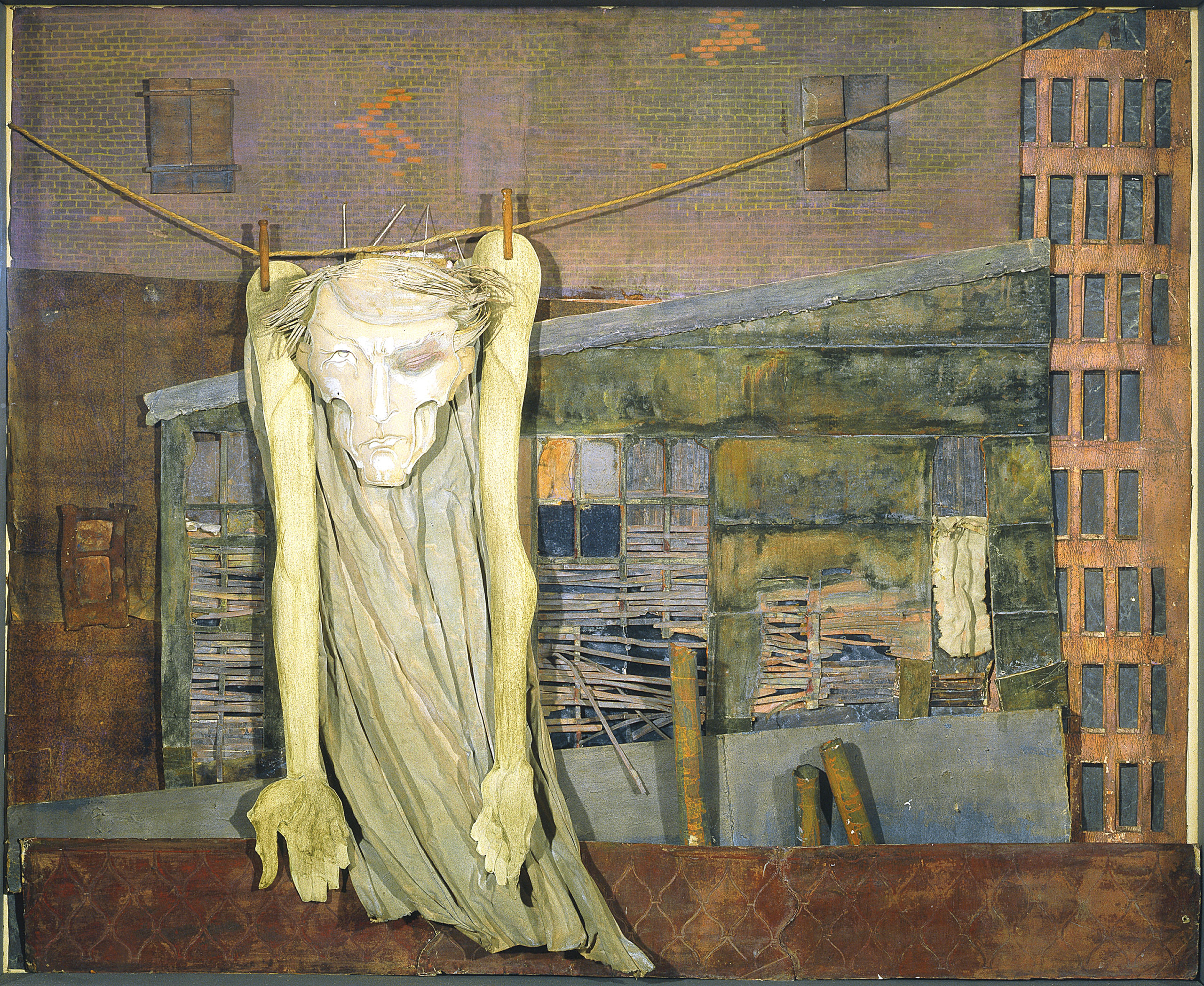

“Moons I” by Mina Loy, 1932, mixed media on board, 26¼ by 35¼ inches. Private collection. —Brad Stanton photo

By Kristin Nord

BRUNSWICK, MAINE — The ravishing, multilingual, and multitalented Mina Loy was an astonishing poet, inventor and visual artist. Yet throughout much of the Twentieth Century, her work as a visual artist was largely forgotten. “Mina Loy: Strangeness is Inevitable,” running through September 17 at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, is a comprehensive exploration of Loy in all of her expressive colorations. Curated by Modernist scholar Jennifer R. Gross, and greatly aided by Loy’s longtime editor and literary executor Roger L. Conover, the exhibition brings the artist to life and probes the reasons why she has consistently defied categorization.

Loy was born in England in 1882 to Sigmund Lowy, a Jewish immigrant and the highest-paid tailor’s cutter in London, and Julia Bryan, a conservative working-class woman. Lowy, who came from a wealthy family in Budapest, was handsome and erudite and was known for his delicate paintings of English flowers. From an early age, Mina chafed at her mother’s Victorian sense of propriety, but relied upon her father for emotional and financial support.

Sigmund had recognized his precocious daughter’s talent and paid for her art studies in London, Munich and Paris. She was in her early twenties when her watercolors were accepted for an exhibition at the prestigious Salon d’Automne. She would exhibit four more times between 1905 and 1923 and was elected a member of its drawing society in 1906. She would also embark upon an unhappy marriage to the photographer Stephen Haweis. He proved no match for his wife’s intellect or multi-faceted talents, but the two held on for financial reasons for a decade before their divorce became official. Their move to Italy was one of many disruptions that would beset her life and career.

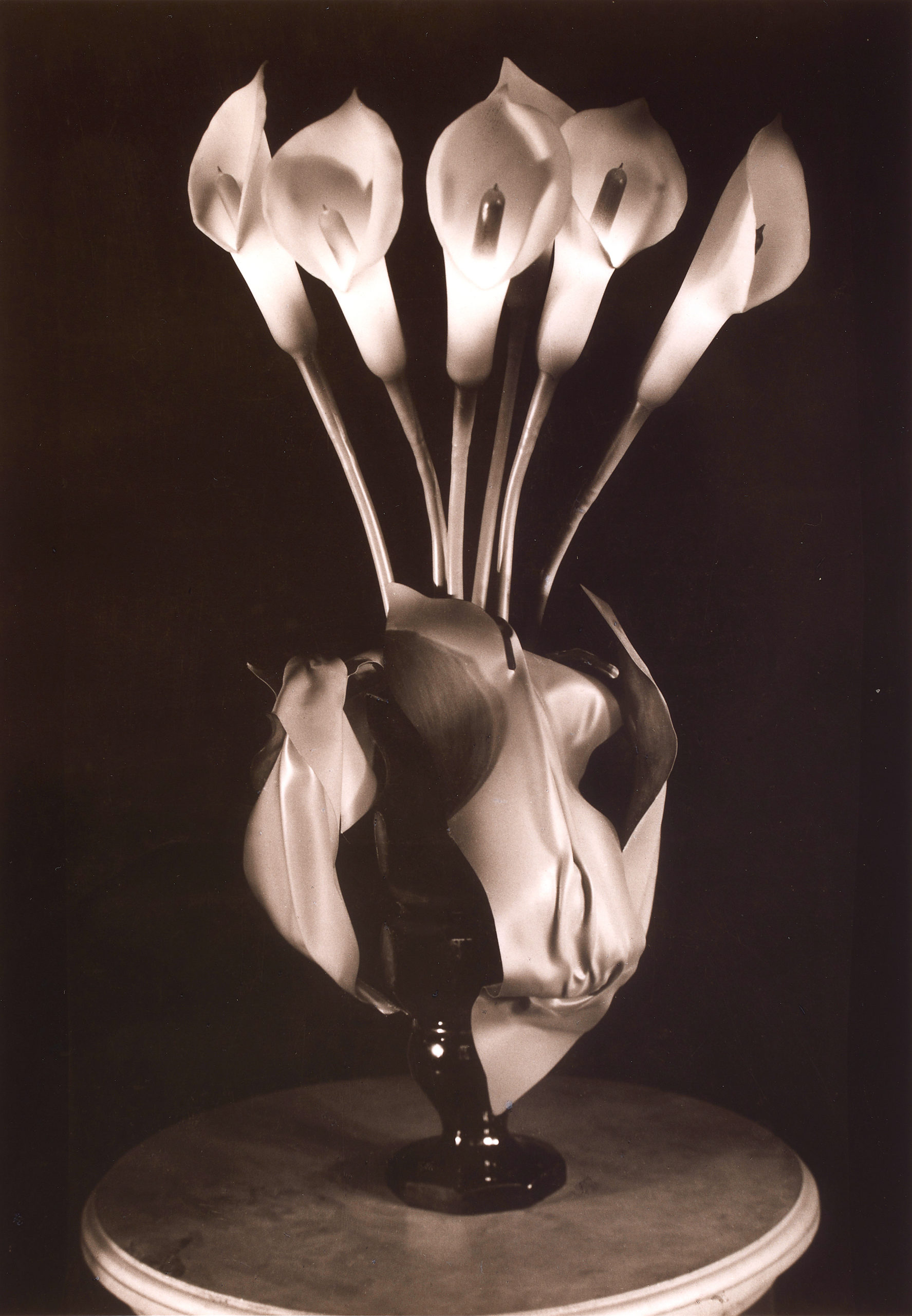

“Mina Loy” by Man Ray, 1920, gelatin silver print, 6½ by 5-1/8 inches. Private collection. Photography by Luc Demers. Man Ray ©Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2022.

While Loy would operate on the fringes of the leading “isms” of the day, she would remain an original thinker. By 1916, when she arrived in New York, she soon learned that her reputation as a poet had preceded her. In Becoming a Modern: The Life of Mina Loy (Univ of Calif. Press, 1997), Carolyn Burke writes that Loy’s often frankly erotic subject matter shocked the establishment as much as her elimination of punctuation marks and the audacious spacing of her lines rocked the sensibilities of the poetry reading audience.

The young radical was welcomed into the fold of Walter and Louise Arensberg’s Salon on West 66th Street, where a cosmopolitan group of artists and writers gathered nightly to gossip, play chess and analyze each other’s dreams, the biographer continued. In this atmosphere, the emphasis was on the new — whether psychoanalysis, free verse, free love or Cubism — and it was where Loy kindled a number of friendships.

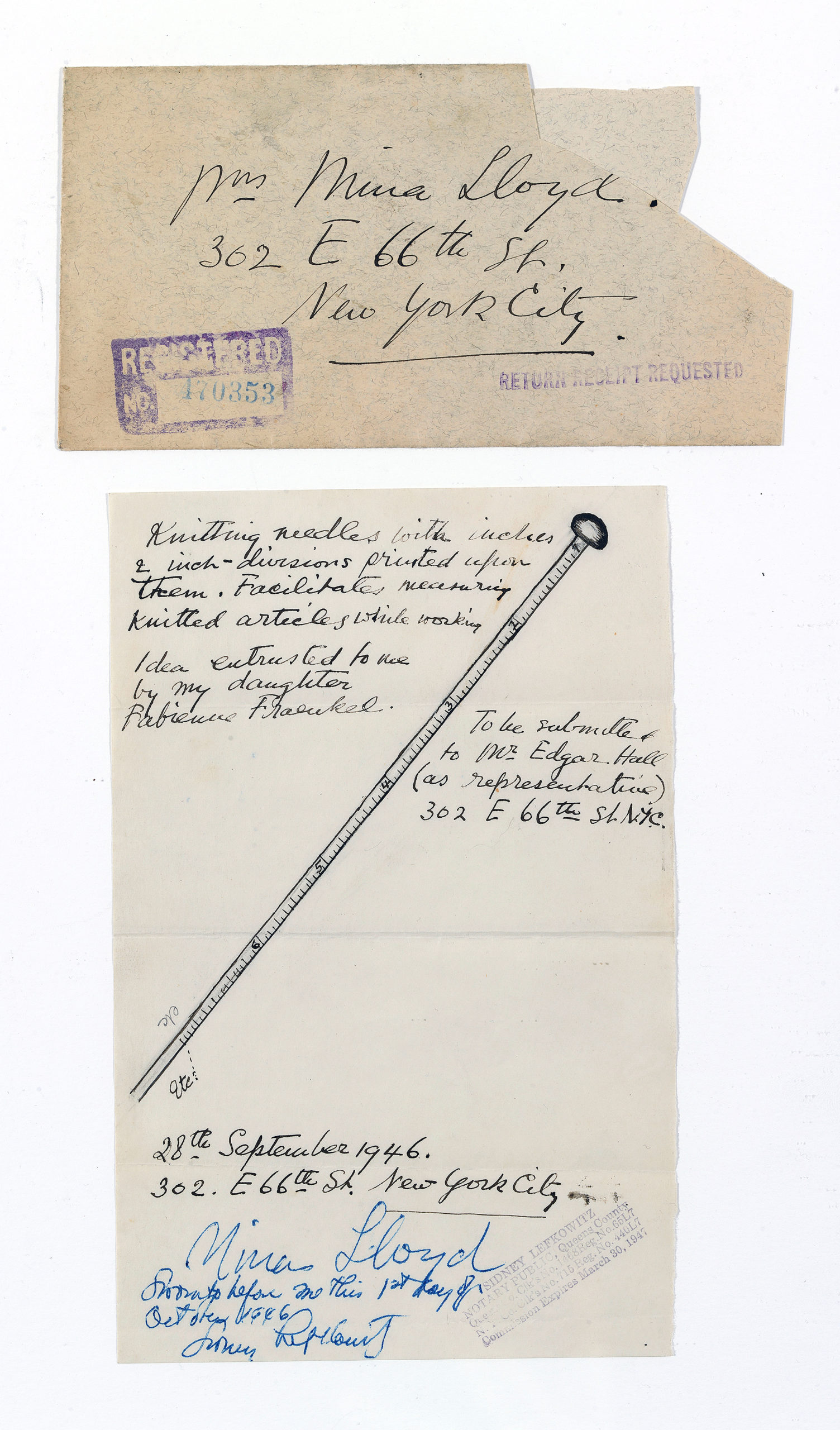

Creativity coursed through her veins and was channeled into commerce, inventions, fashion, interior design; free-verse poetry, essays, manifestos, watercolors, pencil drawings, paintings and art criticism. While some of these ventures were inspired by necessity, all flowed from the same tributary.

“Mina Loy Dressed for the Blindman’s Ball” by unidentified photographer, 1917, gelatin silver print on paper, 5½ by 8-7/16 inches. Private collection. —Luc Demers photo

“The modern flings herself and lets her feel what she does feel, then upon the very tick of the second she snatches the images of life that fly through her brain,” Loy announced. From this stance, she unleashed an unrelenting critical eye upon the worlds of art, culture, politics, society and herself. Her responses could be as withering as they were revelatory, commanding the New York avant-garde’s attention to her every word. Of the eminent poet Marianne Moore, she sniffed, Moore’s poetics “suggest the soliloquies of a library clock.” She was equally dismissive of T.S. Eliot’s translations of the writing of Paul Valery, likening the encounter to “falling down a vegetarian’s lavatory.”

She no doubt turned heads when she arrived at the legendary Blindman’s Ball outfitted as a lamp shade in 1917. Illumination — physical, metaphysical and spiritual — would surface in her creative pursuits throughout her life in a series of surrealist paintings as well as in a line of custom-designed lamps and shades that for a time had the backing of Peggy Guggenheim. The works were constructed from — and inspired by — materials she scavenged from Paris’ flea markets, and they brought Loy international recognition as a designer.

Tragedy would intrude upon her life and would include the deaths of two children and the disappearance and presumed death of Arthur Craven, the love of her life and her second husband. At various times she was weighed down by recurring clinical depressions and the very real need to support herself and her two daughters.

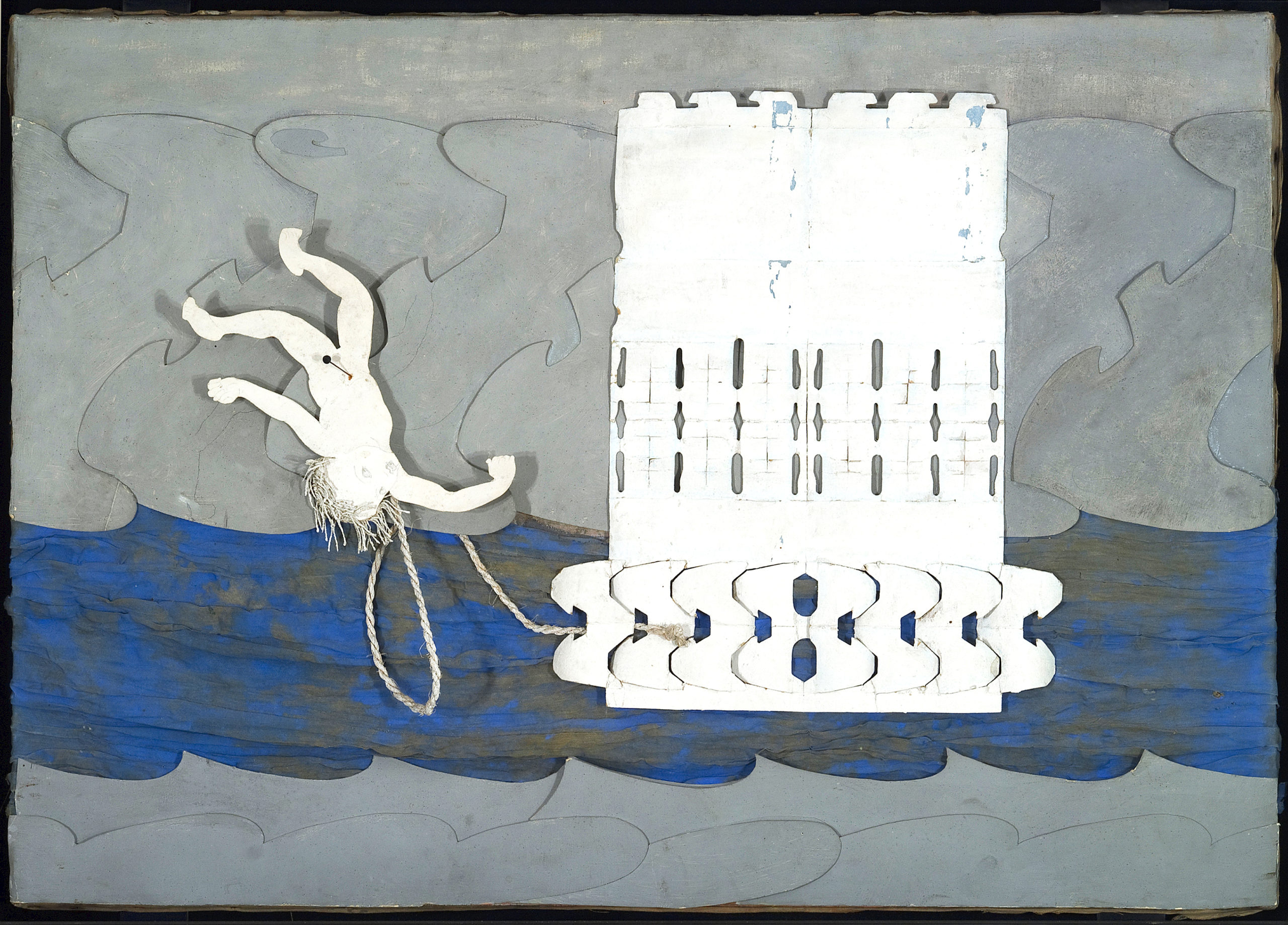

Untitled (The Drifting Tower) by Mina Loy, circa 1950, cut-paper and mixed-media collage on canvas, 28¾ by 39 inches. Private collection. —Jay York photo

After the life-threatening illness of her daughter, Joella, which she believed had been cured by ministrations of a Christian Science healer, she became a lifelong convert. In several Surrealist paintings exhibited in a 1933 solo show at the Julien Levy Gallery, she appears to be probing a celestial netherworld inhabited by bodyless heavenly hosts. The fellow Christian Scientist and artist Robert Cornell wrote her that encountering this work had been transformational for him. The two, who shared the belief that art was a divine calling, became friends for life.

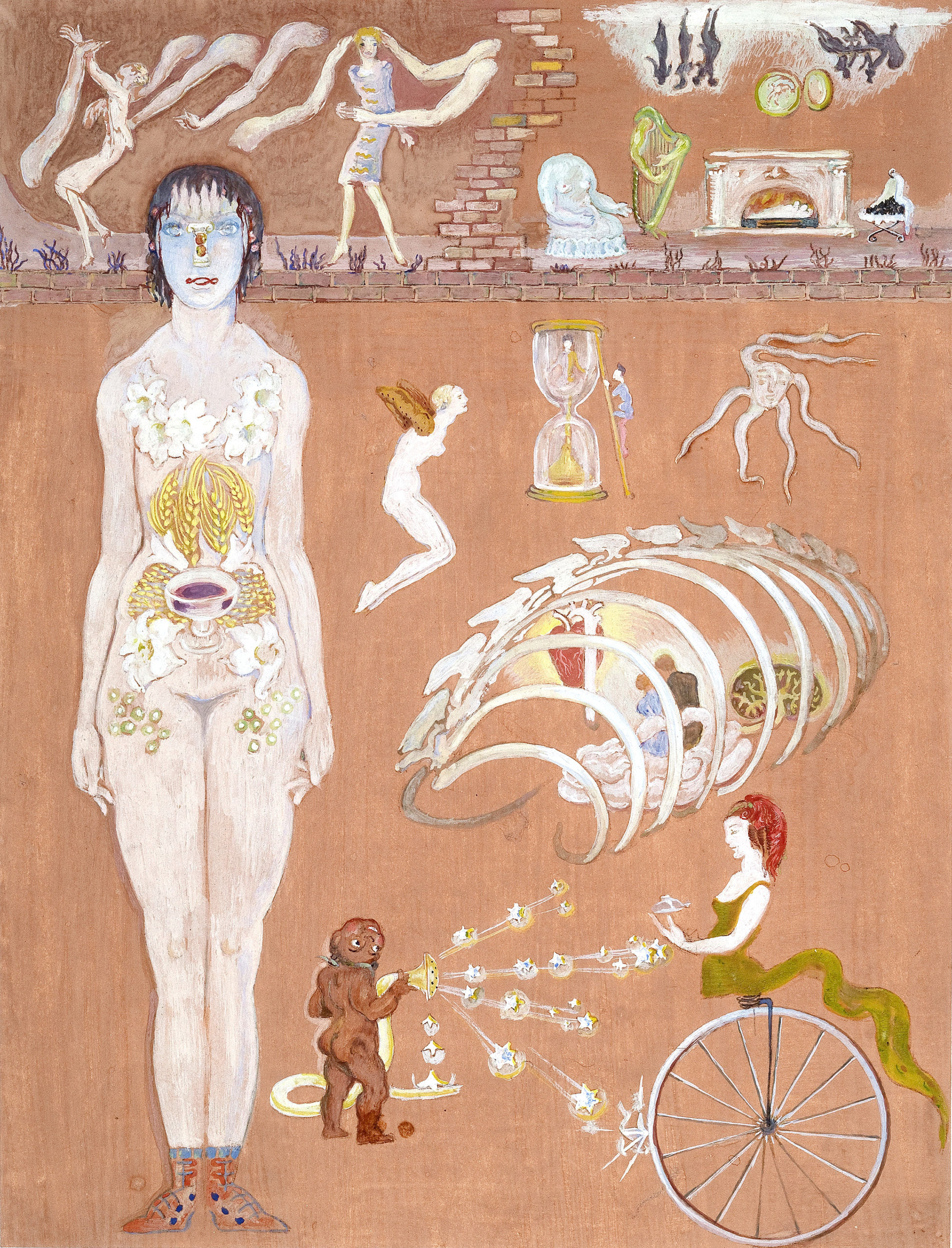

In yet another mysterious work, a gouache with collage on panel, Loy responds to the tale of Jonah and the Whale with symbols of rebirth: the Greek goddess Persephone’s wheat sheafs, lotus blossoms and the Christian chalice for communal wine. The man and woman encased in the whale’s ribs could well be Loy and Craven themselves, finally reunited. The painting, Gross suspects, may have been constructed jointly by Loy and her daughter, Fabi, as a form of cadavre equis, the Surrealist game in which multiple artists complete a work together.

The exhibition has been organized chronologically, with particular emphasis on the artist’s years in Germany, Italy, France and The United States. There are archival materials depicting her liaisons with leading Futurists, Filippo Tomasso Marinetti and Giovanni Papini, and examples of paintings that appeared in the 1933 exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery, when it was known as a New York showcase for Surrealism and its roster included Duchamp, Max Ernst, Man Ray and Alexander Calder. It concludes with her large-scale media assemblages, including a number made in Aspen, Colo., where she lived for the last 13 years of her life.

“Communal Cot” by Mina Loy, 1949, cut-paper and mixed-media collage mounted on board, 27¼ by 46½ inches. Private collection, Chicago. —Michael Tropea photo

The exhibition, which will travel to The Arts Club of Chicago after its run ends at Bowdoin, features 60 paintings, drawings, instructions, designs, inventions, letters and original copies of her published poetry. There are additional art works by a veritable Who’s Who of the avant-garde, including Berenice Abbott, Joseph Cornell, Lee Miller, Man Ray, Umbo and Beatrice Wood; letters, photographs and archival materials on loan from nearly a dozen institutions and private collections; and a catalog with essays by Gross, Conover and poet Ann Lauterbach and the Surrealist scholar Dawn Ades.

“We are honored to give Mina Loy her due as a catalyzing figure in European and American modernism,” Anne Collins Goodyear, co-director of the museum, said recently, “and to recognize as new scholarship emerges, that her importance is more obvious today than it was in her own lifetime.”

As a young artist, Loy had gravitated to small-scale genre scenes of working-class women and she had depicted weavers, hat makers and performers. In her later years, she was drawn increasingly to people who were living on the fringes of society.

“As she got older,” Conover asserts, “her art got better and better.” By the 1950s she was living on Stanton Street in Manhattan and had trained her lens on her neighbors in The Bowery. She was crafting multidimensional constructions from humble materials which belied the extraordinary care with which she captured the nuanced personalities of her subjects. One can’t help but leave with food for thought, after encountering her “Christ on a Clothesline,” or her portrayal of her neighbors, splayed out like specimens on a concrete slab in the work she titled, “Communal Cot.”

“Christ on a Clothesline” by Mina Loy, 1955-59, cut-paper and mixed-media collage, 24 by 41½ by 4½ inches. Private Collection. —Dana Martin-Strebel photo

When the Stanton Street constructions were finally exhibited in 1959, it was thanks to the intervention of Duchamp, Julien Levy and David Mann, an art dealer. For the invitation card Duchamp wrote: “Mina’s Poems A 2½ Dimensions: Hauts-Reliefs and Bas-Fronds, Inc., Duchamp (Admiravit).” Marveling at these visual poems poised between two and three dimensions, Duchamp played on the technical terms for sculpture in high or low relief to allude to other dimensions of high and low — implying the marriage of spiritual elevation and the depths of human existence.

In her final years, Loy’s now-grown daughters had spirited her away to Aspen, where she somewhat reluctantly lived and worked right up until her death in 1966. Three late works — “Prospector I” (1954) and “Prospector II” (1954) and “Sander Gear” (1955) evoke the region’s mining history. And the works themselves anticipate the arrival of Pop art and conceptualism. “She made art from trash long before dumpster diving was a thing and multimedia was a term,” Conover said.

Gross writes, “While literary historians have embraced the breadth and force of her written work, art historians have yet to fully acknowledge the modern marvel that was Mina Loy. Her omnivorous creativity defied categorization, and her superlative, complex persona deflected focus. The artist Mina Loy was at once a shooting star, a lunar beacon and a constellation all to herself.”

“Mina Loy: Strangeness is Inevitable” is on view at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, at 245 Maine Street, through September 18. For more information, 207-725-3275 or www.bowdoin.edu/art-museum.