By Madelia Hickman Ring

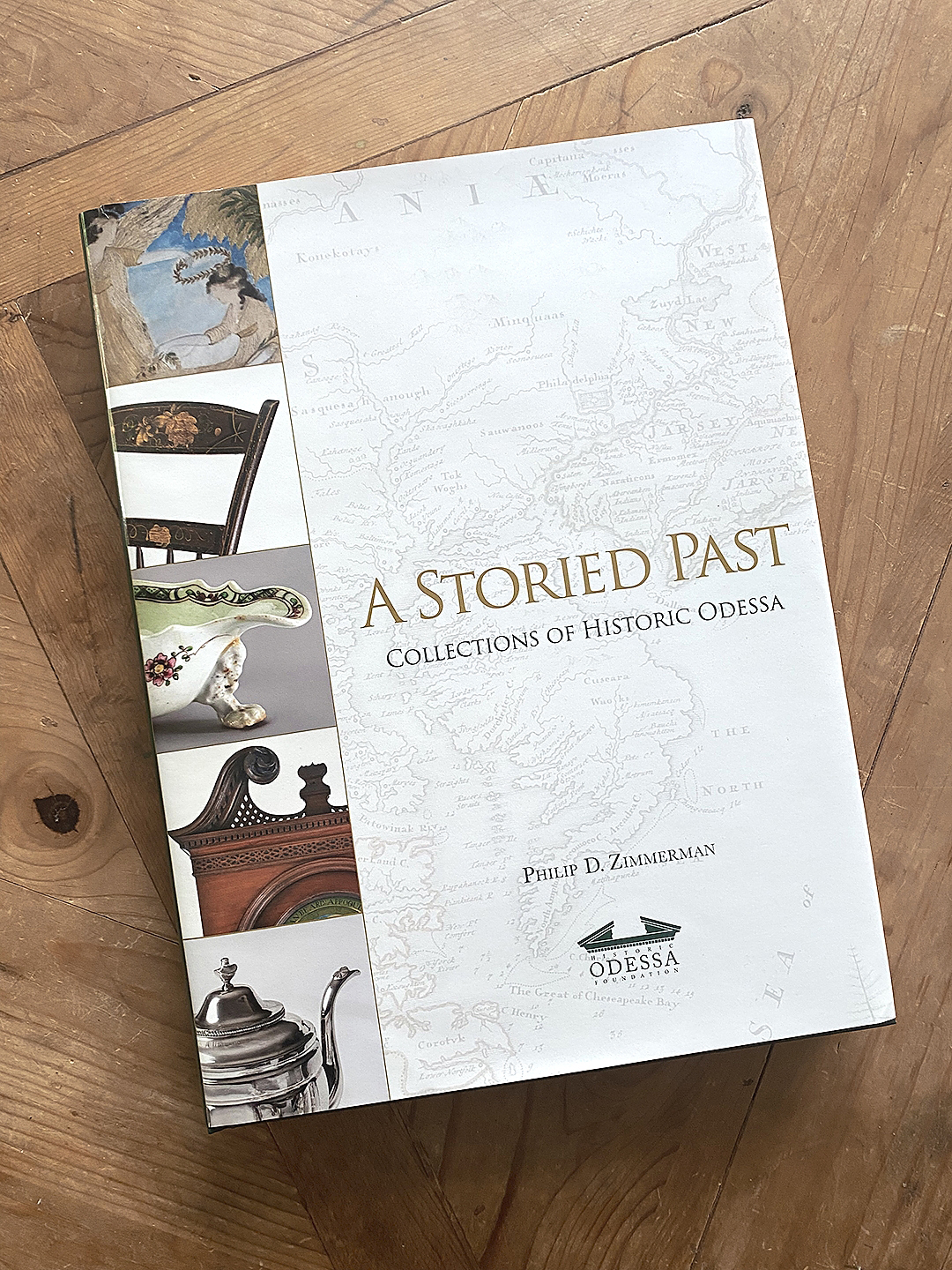

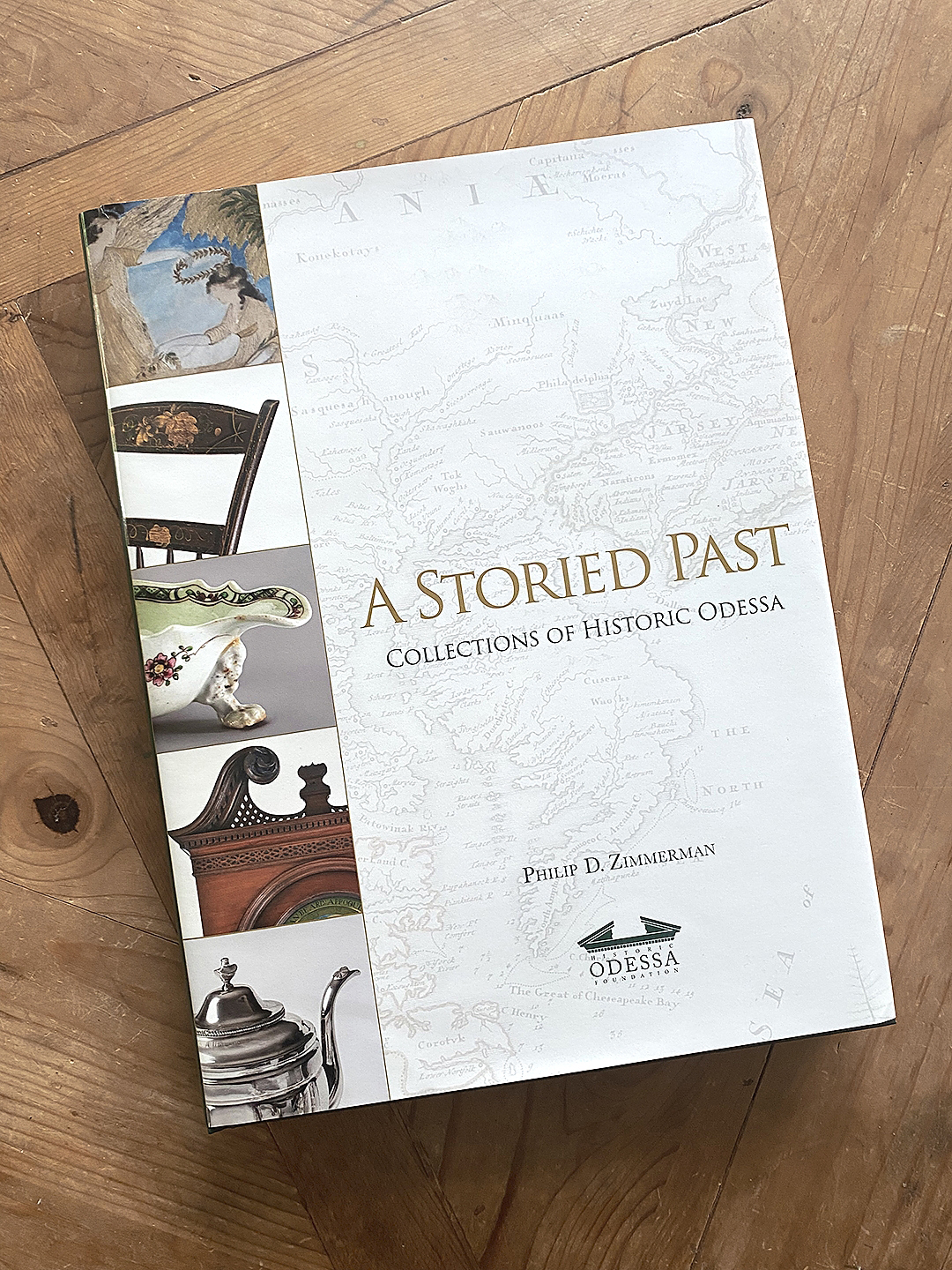

ODESSA, DEL. — Furniture and decorative arts made in Delaware in the Seventeenth, Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries have been generally overlooked by scholars, connoisseurs and collectors, who have historically preferred to focus more closely on the material culture and output of the cabinetmaking shops — and craft-making centers — of Philadelphia, New York City and Baltimore. A new publication by the Historic Odessa Foundation and written by furniture scholar and museum consultant Philip D. Zimmerman, PhD, A Storied Past: Collections Of Historic Odessa, sheds invaluable light on an under-explored area of the field and is a must-have addition to any decorative arts library.

The book focuses on the early family collections at Historic Odessa, centering on two of the five historic properties owned by the Foundation: The Wilson-Warner House (1769-1771), and the Corbit-Sharp House (1772-1774). Both houses are veritable time-capsules; the former was purchased in 1901 by Mollie Warner (1848-1923), a descendant of both the Wilson and Corbit families. She furnished it with both family and personal things, and, upon her death in 1923, the house became the first historic house opened to the public in Delaware. The Corbit-Sharp house, on the other hand, remained in the Corbit family until 1938, when it was purchased by H. Rodney Sharp, the husband of Isabella du Pont. Sharp restored the house and added some additional furnishings, including some important local and Corbit objects, and gave the house to Winterthur in 1958. Ten years later, the Wilson-Warner House board voted to merge their collections with Winterthur as well.

High chest of drawers, Odessa area, or Wilmington, Del., 1760-1785. Historic Odessa Foundation.

Winterthur’s collection of furniture from Odessa was augmented when Margaret Janvier Hort, a descendant of Delaware’s Janvier family of cabinetmakers approached the museum and curator John A.H. Sweeney with Janvier-made furniture, furnishings, manuscripts and more that she had acquired from family members.

In 2003, Winterthur closed the historic properties and recommended selling them, a move that inspired Rodney Sharp’s granddaughter, H. Donnan Sharp, who was then on the Winterthur Odessa Committee, to object. Within two years, the Historic Odessa Foundation was established and acquired the properties and collections from Winterthur.

Despite being intact and voluminous, the collections and furniture at Historic Odessa had previously enjoyed only sparse research and publication. In January 1942, Leon de Valinger Jr published an article in Antiques magazine titled “John Janvier, Delaware Cabinetmaker”; the same publication featured an article by Sweeney on the Corbit House in January 1954. By April 1981, Historic Odessa and its collection were the subjects of several articles in Antiques magazine.

Dining table, John Janvier Jr (1777-1850), Odessa, Del., 1795-circa 1801. Historic Odessa Foundation.

“What captivated me about Odessa, specifically, was the furniture made by John Janvier and his progeny was as good as almost anything made in Philadelphia,” notes Zimmerman. “And it’s the best-documented part of the collection. Being able to document the historical sources is key to understanding the material. When you have documentary evidence to support provenance, it’s critical to integrate that into the study of objects; it creates a need to go down as many research avenues as possible.”

Zimmerman’s connections with Historic Odessa began early; chairs belonging to the Corbit family were included in his MA thesis for Winterthur, which focused on Philadelphia chairs. Over the course of the past 40-plus years, he has published extensively on Delaware decorative arts, including articles for Chipstone’s journal, American Furniture (2017) and Antiques magazine (May and September 2001). He curated the 2014 loan exhibition for the Delaware Antiques Show, which was titled “Historic Odessa: A Past Preserved,” and was a furniture consultant to the Sewell C. Biggs Museum in Dover, Del. During this tenure, he wrote furniture entries for The Sewell C. Biggs Collection of American Art: A Catalogue (2002) and later authored for the museum, Delaware Clocks (2006).

A Storied Past: Collections Of Historic Odessa not only shines a bright light onto Historic Odessa’s rich collections but elevates the level of scholarship through Zimmerman’s methodology of relying on the surviving historical documentation, with profuse footnotes throughout. Four chapters preface the catalog itself, the first and second elaborating on the history of the area, from its settlement in the early Seventeenth Century, and the families who lived there. A chapter titled “Craftsmen” outlines some of the construction and ornamentation differences between furniture made in Odessa and surrounded Delaware environs, and that of Philadelphia, the urban city center that cast a long shadow of influence among neighboring regions. It is the fourth chapter, on “Preservation,” where Zimmerman singles out how important preservation efforts — in the form of physical tags and labels on furniture as well as documentary evidence — by successive Odessa residents who contributed to the bulk of material available to scholars today.

Dressing stand, probably Philadelphia, 1825-1850. Historic Odessa Foundation, gift of Sarah Corbit Reese Pryor, 1974.

Armed with all this preparatory knowledge, even the casual reader will be eager to see the collection. The catalog of exactly 100 objects is furniture-centric, with the first 59 entries devoted to tables, case pieces, clocks, mirrors, chairs and beds, either made in Delaware or Philadelphia, or with histories of ownership by Odessa families.

The earliest piece of furniture noted as having been made in Delaware is a walnut high chest of drawers, made in Odessa or Wilmington, 1760-85, that was originally owned by David Wilson and last in the collection of Mary Corbit Warner.

The first piece included with an attribution to John Janvier Sr (1749-1801) is a mahogany desk and bookcase made in Odessa circa 1775, one of just two pieces of furniture named in the 1818 will of William Corbit (1746-1818). Influences of Philadelphia cabinetmaking are evident, but the catalog entry points to several construction or ornamentation details that identify its Delaware origin. The other piece of furniture listed in Corbit’s will is a circa 1775 mahogany tall clock in a case attributed to Janvier Sr and with an eight-day movement clock by Duncan Beard (working 1765-1797).

Tall clock, Odessa, Del., circa 1775, eight-day movement by Duncan Beard (w 1765-1797), case attributed to John Janvier Sr. On loan from Winterthur, gift of Mrs Earle R. Crowe, 1973.

Several objects long thought to have been made in Philadelphia have, through Zimmerman’s examination, been reconsidered and now bear attribution to Odessa. Such is the case with a set of chairs — originally six side chairs and two armchairs, but for the catalog only three side chairs and one armchair are discussed — has been recatalogued with an attribution to Janvier Sr based not least on its heavily documented provenance through several generations of the Corbit family and elements of construction.

A dropleaf mahogany dining table made between 1795 and 1801 by Janvier’s son, John Janvier Jr (1777-1850) is the first introduction to other cabinetmaking members of the Janvier family, who also include Thomas Janvier (1772-1852). The catalog entry states, “Of the several dining tables with location associations at Historic Odessa, this…is the best documented”; it features a chalk signature underneath its top.

A chapter on furniture made in Smyrna, Del., illustrates the other regional cabinetmakers whose goods and services were readily available to residents of Odessa. As in other chapters, details of furniture construction and decoration are discussed in great detail, likewise for a selection of Windsor, fancy and turned chairs. Capping discussion of Historic Odessa furniture is a look at “Late Furniture.”

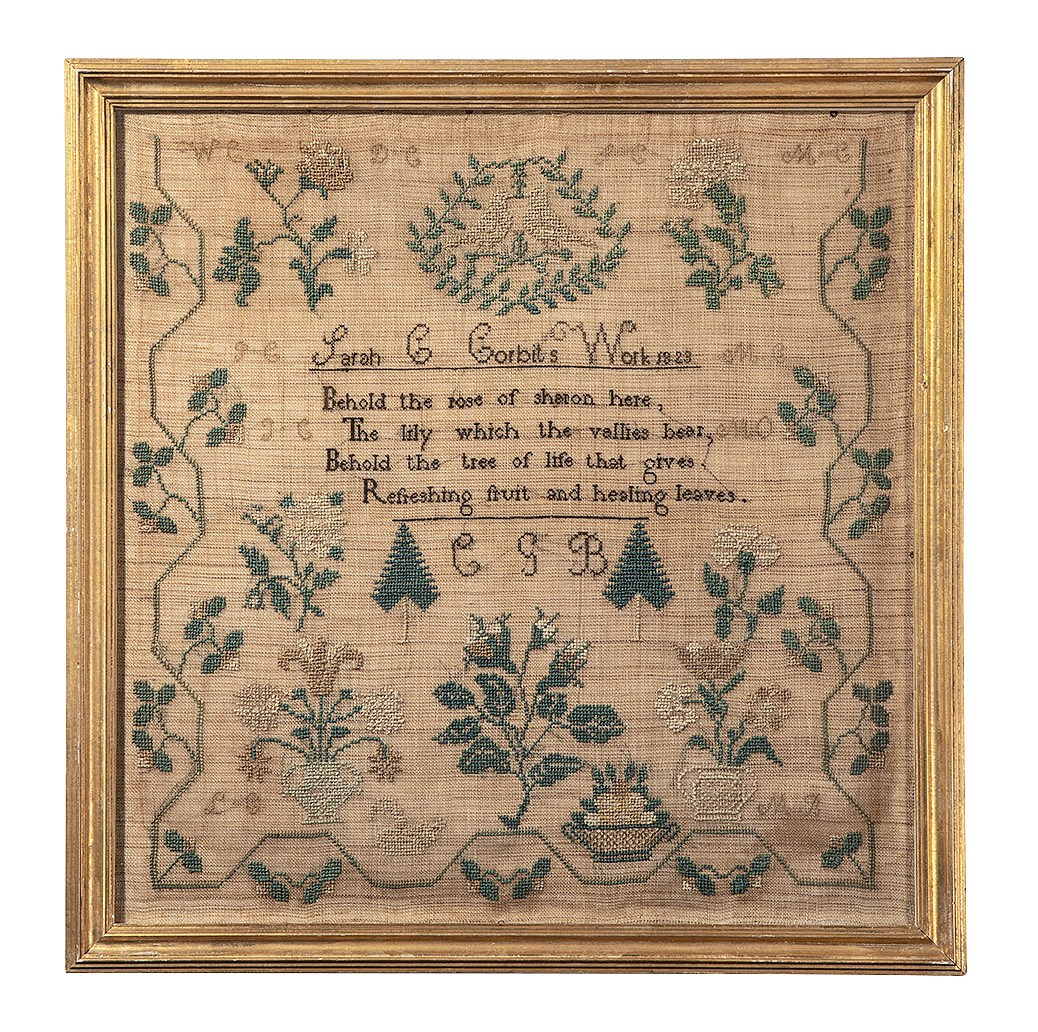

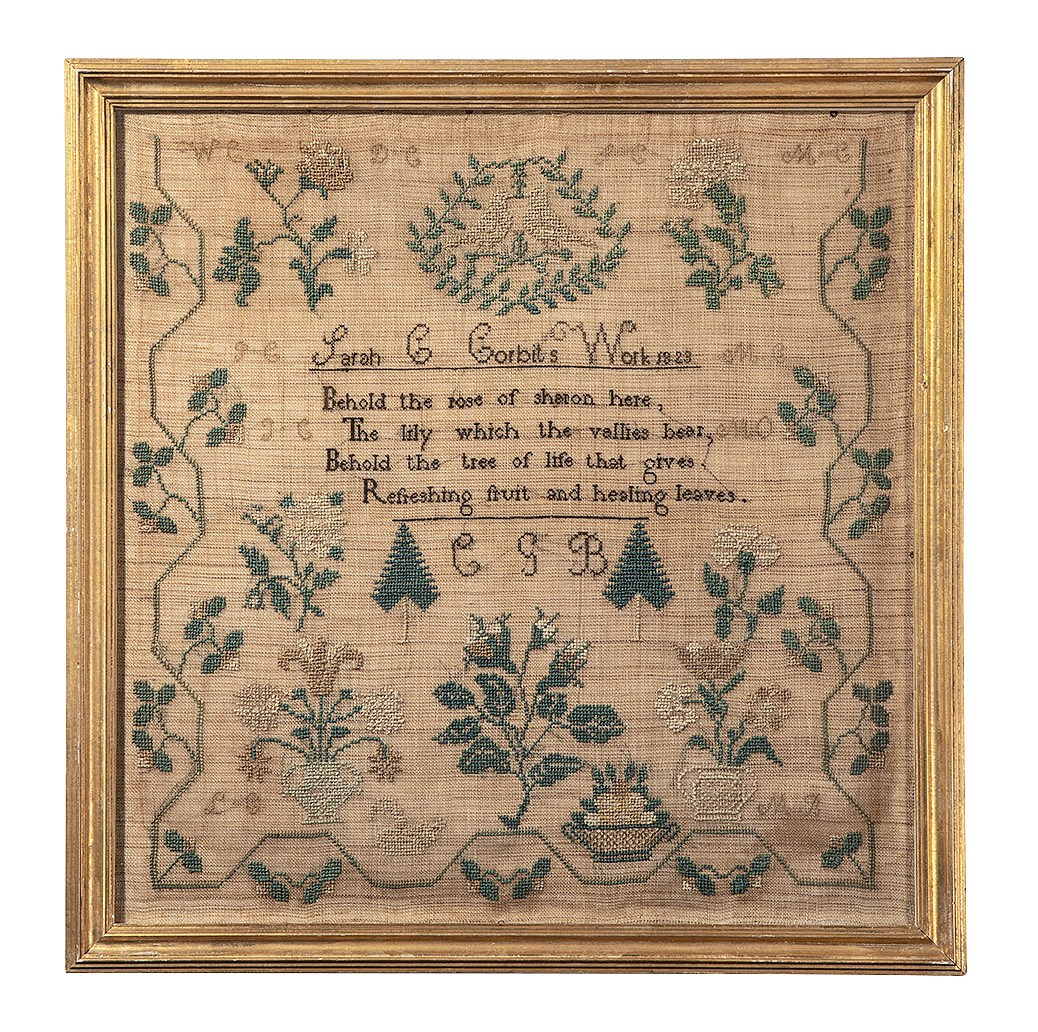

Samplers worked by members of the Corbit family — Sarah Clark Corbit (1810-1871) and Mary Pennell Corbit (1812-1875) usher readers into the textiles section, which also includes several pocketbooks owned by Corbit family members, a Folwell School silk needlework picture probably made by Ann Jefferis Wilson (1791-1822) and a Corbit family signature quilt made in Odessa between 1842 and 1844.

Needlework sampler, Sarah Clark Corbit (1810-1871), Odessa, Del., 1823. Historic Odessa Foundation, gift of Sara Corbit Reese Pryor, 1977.

Among English- and Philadelphia-made silver is a three-piece coffee service made in Wilmington, Del., circa 1808, by Thomas McConnell (1768-1825) that had a complicated provenance before it ended up with Mary Corbit Warner.

Following the catalog, the book includes a short title bibliography that identifies most of the scholarship to date. In his introduction, Zimmerman makes special mention of John Sweeney’s 1959 book, Grandeur on the Appoquinimink: The House of William Corbit at Odessa, Delaware (Newark, Del.), which A Stored Past wraps in the sense that it does not address the building of the Corbit house, which has been documented by several accounts. Zimmerman acknowledges that he could never have moved forward without Sweeney’s genealogical work with the family.

The catalog rounds out with ceramics, non-silver metalwork, musical and other instruments, paintings and prints of — and by — notable Delaware residents, and maps of the region.

“The collections at Historic Odessa demonstrate that new scholarship readily emerges from well-worn paths. Ground-breaking research of years past brings objects and information to light, allowing us to research more broadly and deeply and to arrive at more compelling interpretations,” Zimmerman concludes.

A Storied Past, Collections of Historic Odessa by Philip D. Zimmerman, published by the Historic Odessa Foundation, Odessa, Del., 2023, Distributed by Rowman & Littlefield (Lanham, Boulder, New York & London); 272 pp., 200+ color illustrations, hardcover, $75. An e-version is also available, for $45.