Melissa Tedone photo.

A dedicated reader tipped off Antiques and The Arts Weekly about the “Poison Book Project,” an ongoing investigation currently undertaken by Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library and the University of Delaware to identify potentially toxic pigments used in Victorian-era book bindings. Safe to say, we were dying to know more about it and reached out to Dr Melissa Tedone, the lead conservator and lab head for library materials conservation at Winterthur, for more insights.

“Poison Book Project” is a pretty provocative title — are there really such things as Poisonous Books out there?

Indeed there are! I agree that the project title comes across as a bit sensational. That has helped us grab people’s attention, but it is also a quite literal description. The books we research were produced during the Nineteenth Century and contain significant amounts of poison — lead, chromium, and most toxic of all, arsenic — in their bright and attractive colors. We were frankly astonished when we first discovered how much arsenic was present in some mass-produced, Victorian-era books. So, we chose a project title that would clearly communicate this surprising fact to our colleagues and the public.

Are they truly lethal? Can they be made non-lethal?

Arsenic-containing books certainly have the potential to be lethal — depending on how they are handled and who is handling them. First and foremost, these books should be kept out of the reach of children and pets. Arsenic toxicity is a function of body weight, so it takes a much smaller dose to be deadly for a pet or a child than for an adult. Small children and pets also interact with books more unpredictably than adults. For instance, most adults will not put a book in their mouth. However, toddlers and dogs might do just that. While an adult would likely have to lick a “poison book” in order to ingest a lethal dose of arsenic, you could be exposed to smaller amounts of arsenic by eating, drinking or touching your face while handling such a book. That smaller exposure could still be enough arsenic to make you unpleasantly ill or contribute to chronic health problems down the road.

Example of an emerald green book in a labeled, zip-top, polyethylene bag. Courtesy Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library.

It is the bright green colorant itself (“emerald green” or copper acetoarsenite) that contains the arsenic, so there is no way to remove the poison from the books without removing the green component — whether that is a book cover, endpapers, a spine label or bright green text-block edges. The testing we have done so far suggests that books covered with emerald-green cloth are the most potentially hazardous. The arsenic in the bookcloth offsets easily onto the hands and other surfaces. You won’t see the color transferring onto your hands or the bookshelf, but the arsenic is still transferring in a measurable amount. Emerald-green papers have been used to cover the outside of books, as spine labels and decorative elements on book covers, and as endpapers inside book covers. We’re still performing tests to figure out whether or not emerald green pigment is more stable on paper than cloth. Until we know more, all arsenic-containing books should be handled with caution.

We’ve found that bright orange, yellow, red and non-arsenical green cloth-covered books may contain chromium and lead, which are also toxic heavy metals. However, the chromium and lead don’t appear to offset onto hands and other surfaces the way arsenic does. So, while we still recommend book lovers avoid eating and drinking while handling any Nineteenth Century cloth-bound book, these books do not require gloves to handle. We also strongly suggest washing your hands with soap and water after handling any historical bookbinding, just in case!

How did this project get started?

Serendipity! It was really a matter of being in the right place at the right time. In early 2019, Winterthur Library’s copy of Rustic Adornments for Homes of Taste (2nd ed., 1857) came to our library conservation lab for treatment in preparation for an exhibit. I was familiar with recent research into arsenic-containing Victorian wallpapers. So, when I noticed the bright green colorant flaking off the bookcloth as I was working with it under the microscope, I got curious.

Luckily, Winterthur has a well-equipped scientific research lab and a team of talented conservation scientists who love helping conservators, curators and research fellows answer questions about material culture. So, I turned to my colleague Dr Rosie Grayburn to find out whether the green colorant could be an arsenic-based pigment. She performed analysis using x-ray fluorescence, or XRF. XRF is what we call a “non-destructive” method of analysis, meaning that you don’t have to remove a sample from the material you’re testing. XRF is a safe and reliable way to identify metallic elements (like arsenic and lead) in museum and library objects, so we use this technique a lot at Winterthur. Once we realized we had a mass-produced Nineteenth Century book covered with an arsenic pigment, we felt concerned about how many similar books might be out there in libraries, second-hand bookshops and homes around the world. We knew we had an ethical responsibility to conduct intentional research into this question and to share our findings with the public.

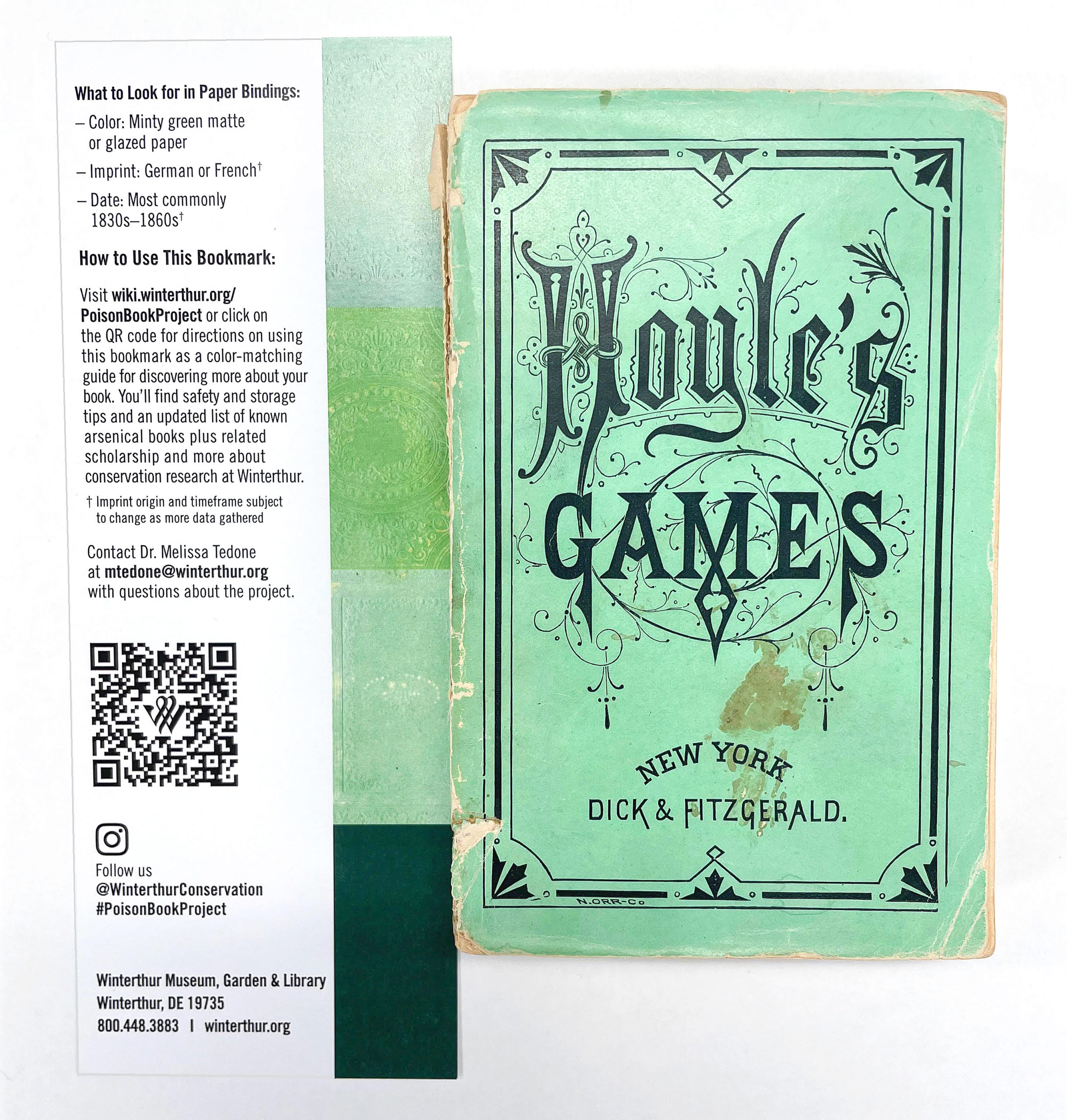

Emerald green color swatch bookmark next to an arsenical paperback book. Courtesy Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library.

Can you elaborate on what the project aims to do?

A strong priority from the beginning has been to share our research widely so librarians, library patrons, book dealers and book collectors are all aware of the potential risk lurking on their bookshelves. An unrecognized arsenic-containing book is an accident waiting to happen. We want to help prevent that accident from ever happening.

We started out identifying emerald green cloth bindings, but soon found out that emerald green pigment can be found in many different bookbinding components. We’re grateful that colleagues at other institutions have taken our lead and started examining their own book collections, too. So, the project has now transitioned to crowd-sourcing data. As colleagues at other institutions have identified more Nineteenth Century emerald green books, they have contributed that data to the Poison Book Project. We use this data to build an ever-growing list of all mass-produced Nineteenth Century books that have been confirmed to contain arsenic. That list is publicly available on our Poison Book Project Wiki, which we update regularly: http://wiki.winterthur.org/wiki/Poison_Book_Project.

At Winterthur and the University of Delaware, we continue to research the materiality of bookcloth and bookbinding papers that contain arsenic, lead and chromium. We’re refining our understanding of how dangerous these elements actually are in books and how these books can be handled and stored more safely. We’re also trying to develop more accessible, affordable ways of testing for arsenic that don’t require an XRF device.

What are some of the volumes that have come to light during the course of this project?

If you’ll forgive my slightly macabre sense of humor, two of my favorite titles include Canine Pathology (London: T.&T. Boosey, 1832) and Nothing to Eat (New York: Dick and Fitzgerald, 1857). Many emerald green volumes are cloth-covered gift books heavily decorated with gold leaf. We haven’t narrowed down a specific genre of book; emerald green books can be novels, poetry, technical manuals and non-fiction. Books covered with emerald green cloth are most often British or North American imprints, with publication dates from the 1840s through the 1860s. Books containing emerald-green paper have a much broader range. Geographically, they could be European (especially French and German) or North American imprints, and their publication dates range from 1816 to 1899. As we continue to collect identification data, we will be able to expand or refine these guidelines accordingly.

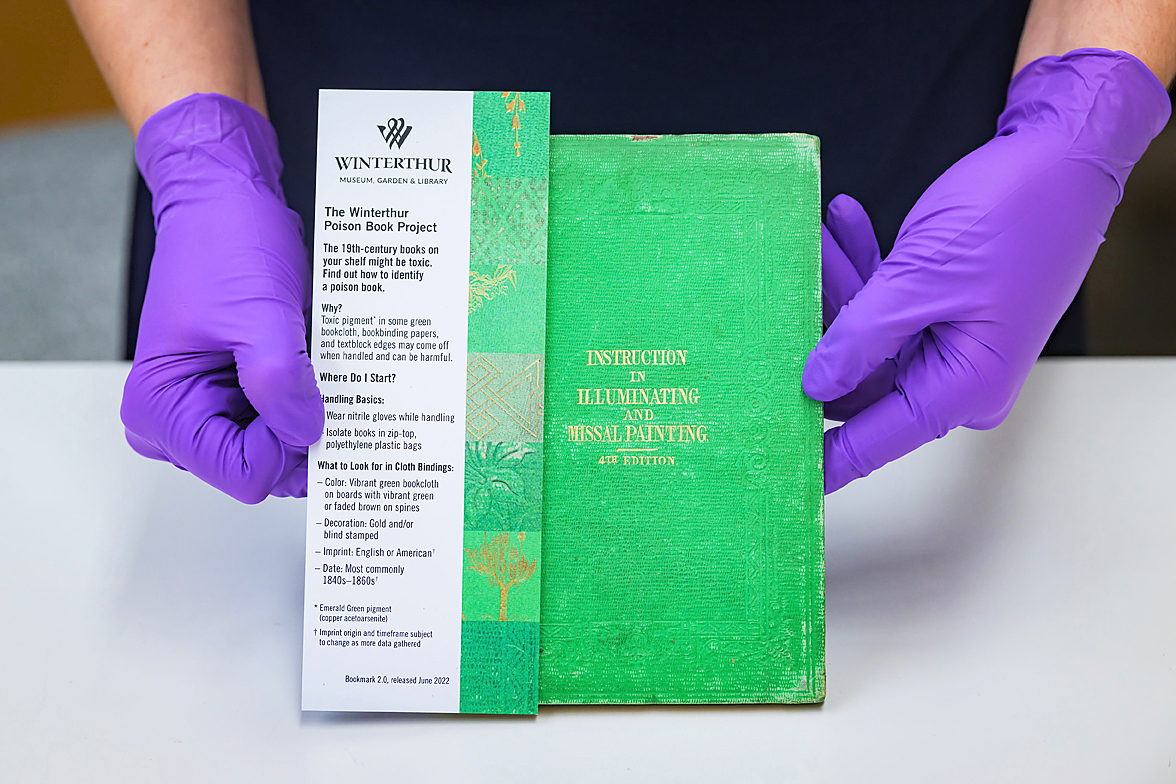

Emerald green color swatch bookmark next to an arsenical, cloth-bound book, with nitrile gloves. Photo credit: Evan Krape, University of Delaware.

How do you and your colleagues remain safe?

If we even suspect a green book might contain arsenic, we wear nitrile gloves to handle it. Nitrile creates a physical barrier so arsenic doesn’t get onto our skin. White cotton gloves are not a good idea, because they are too porous. We isolate the book in a labeled, zip-top, polyethylene bag until it can be tested. The polyethylene bag prevents anyone from handling the book accidentally with bare hands and keeps any arsenic that might shed from the book contained. We then wipe down the surface the book was resting on with a slightly damp, disposable cloth. Winterthur is fortunate to have a relationship with the University of Delaware’s Environmental Health & Safety Department, and their advice has been very important to the project.

If someone suspects they have a “Poison Book” in their library or bookshelf, what should they do?

The Poison Book Project has developed color swatch bookmarks to help book lovers figure out whether they should be concerned about green books in their collection. Those local to Winterthur can stop by the Winterthur Library to pick up a free bookmark. Those further afield can email their postal address to reference@winterthur.org with “Emerald Green Bookmark” in the subject line, and we will mail them a bookmark free of charge. The bookmarks show printed examples of emerald green bookcloth on one side and emerald green papers on the other side. The bookmarks also list other identifying features of arsenical books and a QR code that links to our project wiki.

A box of nitrile gloves can be purchased at most hardware or even grocery stores. Book owners can place any suspiciously bright green book with a publication date in the 1800s into a zip-top, plastic food storage bag for the short term. Even if gloves have been worn to handle the green book, wash hands thoroughly with soap and water after removing the gloves. Our project wiki offers recommendations on how to proceed with further testing to confirm whether a book contains arsenic.

—Madelia Hickman Ring