Deborah Kraft is a Chicago-based painter, sculptor and mixed-media artist whose work spans from wall-sized symmetrical painted reliefs to dazzling miniature collages. Kraft has participated in group exhibitions since 2018 and her second solo show, “Every Beautiful Thing,” is now on view at Seattle’s Supperfield Museum of Contemporary Art through December 30. Antiques and The Arts Weekly corresponded with Kraft to learn more about her enigmatic creations.

Please tell our readers about yourself and your background.

I am a visual artist living and working in Chicago. I grew up a Mississippi river rat, a little bit Illinoisan and a little bit Iowan. I wasn’t exposed to contemporary art growing up, but I had some talent for drawing, so I studied art at Iowa State University, focusing my studies in metalsmithing and painting. In terms of my journey as an artist, I spent the first years after art school working in arts-adjacent fields, first as a fine jeweler, then a gallery manager and art-fair producer, while spending almost all of my limited free time on art-making. I am now a full-time artist.

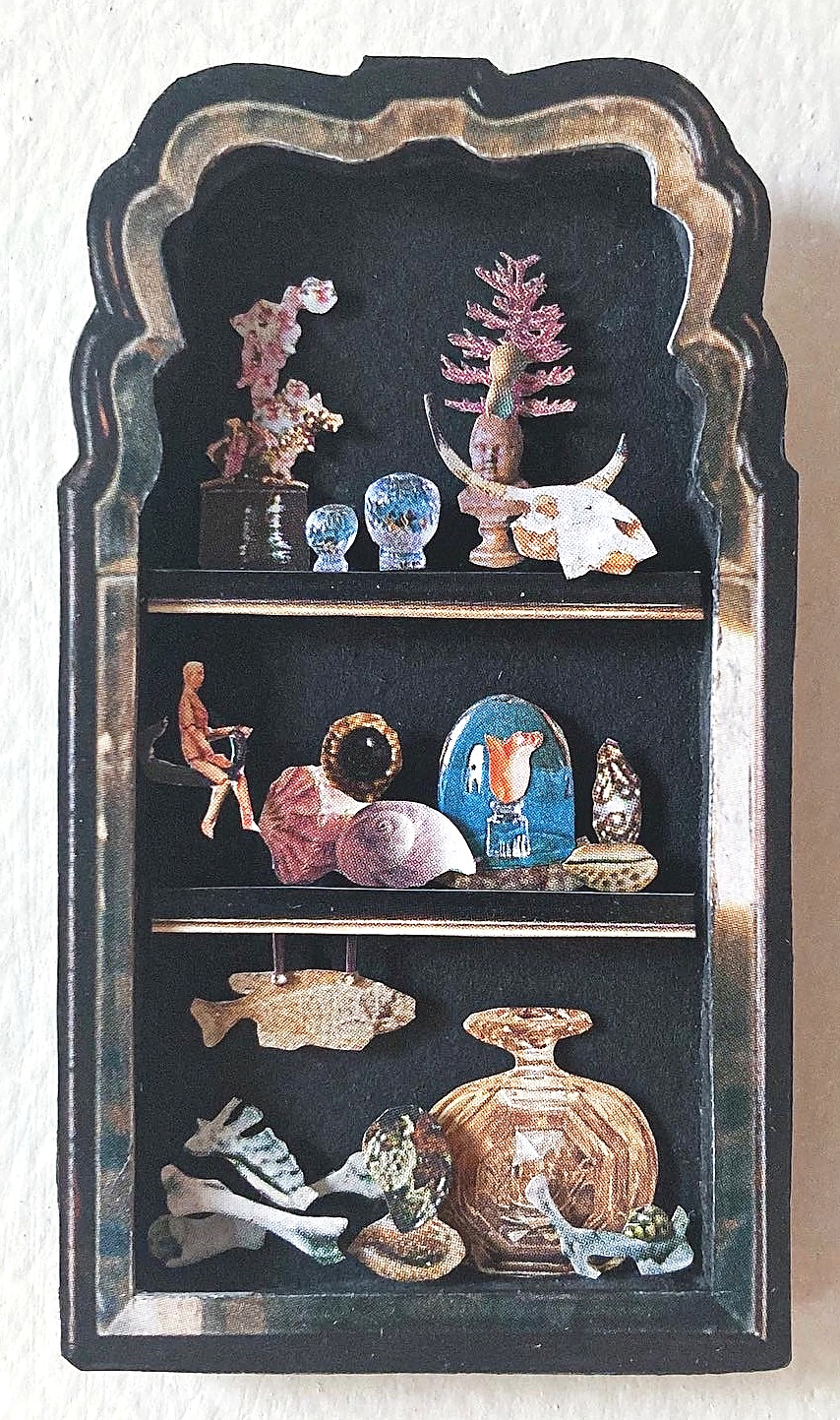

“Cabinet (New Growth),” 2023, collage relief, 4¼ by 3½ inches

In your website’s biography, you mention “experiences both idyllic and frightening,” including fleeing your grandfather’s religious cult to join a girl gang in the forest. How has this influenced your art?

That’s a tricky question. I mention this experience in relation to my art-making because it was so formative. My twin sister and I lived primarily with my grandfather for a relatively short period of time — about two years — while his wife, my grandmother, was dying and he was attempting to faith heal her with the help of potions and prayers from a rotating troupe of the strangest people I ever hope to meet. During this time my sister and I were there to assist with our grandmother’s care, and it was really pretty dark. But a lot of it was also absurdly, bizarrely funny and wild, and then we had this unbelievable little girl gang that seemed to instinctively know what to do to keep us safe. And my sister and I weren’t the only ones in this group who were battling darkness at home. What on one side might look like periods of neglect in our shared childhood were experienced as moments of glorious, untamed freedom.

My grandmother eventually died, of course, because she received no medical treatment. But my grandfather lived for years and continued his influence, to a degree, on my sister and I until he was gone. As far as these girls who I’ve known since we were 6 years old: we’re now spread out geographically, but to this day we share a bond that’s holy — I’m not sure how else to put it. It’s funny that the religion that was crammed down my throat I’ve fiercely rejected, but the whole experience kind of led me to something divine. I think that conflict is visible all over my art.

Who or what are some of your artistic influences?

My art is influenced by such a range of sources — I pick up bits from everywhere. In contemporary art, Sarah Sze is the very top for me. I’m dying to see her current show at the Guggenheim. In terms of painters, Paula Rego really influenced my sense of tough narrative painting. Leonora Carrington and Paulina Peavy introduced me to magic. So many artists in the field of craft and functional art (glass, ceramics, textiles, jewelry and wood) have been an influence on my desire to achieve excellence in craftsmanship. The incredible work of Daniel Brush comes to mind here. I have also long been interested in so-called “Outsider” art. The recently opened Kohler Arts Preserve in Sheboygan, Wis., is home to artists who created whole environments, usually out of their living spaces. I have found so much inspiration from work like Emery Blagdon and Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, who are in the Kohler collection. Lydia Ricci is a magpie. I recently purchased one of her pieces and I can’t get over how fabulous it is. The visionary artist Steve Arnold nearly makes my heart stop. I’m also heavily influenced by the artifice of film design — Jacques Rivette, Powell and Pressburger. Andrei Tarkovsky’s Mirror had a profound effect on my visual life this year.

Where do you source the materials for your art?

I started gathering collage material about 15 years ago by collecting books and publications from thrift stores. Kodachrome imagery from vintage National Geographic magazines was especially significant in my early practice. My day job with a series of national art fairs afforded me the opportunity to claim the surplus copies of promotional magazines that were destined for the dumpster at the close of each fair, and my earlier work included imagery from these sources as well. As this has evolved, I have done my best to diversify my material, and because my work is fairly abstract I can use almost any kind of book or magazine as long as the paper is thick enough to hold up. In my circles, people know me as someone who takes unwanted paper ephemera, so my studio has become full of all kinds of odd books and magazines. Because of this, I now have a rule for new book purchases: for every $2 spent, I need it to contain at least three exceptional images.

“Shrine-Parts,” 2023, collage relief, 3 by 2 inches.

Please expand upon your work as “irreligious shrine-making.”

Due to my own background and witnessing the negative impacts of religion on myself and my loved ones, I distanced myself from it for a significant period of time. However, through my current body of work I find myself delicately treading back in, not towards religion itself, but towards an understanding of the human inclination to focus one’s energy on elevating or glorifying something beyond our understanding. While I am not guided by a religious calling in my artistic practice, I find a certain resonance with artists who are driven by profound religious fervor to create. There is a sense of connection and appreciation that I recognize when encountering Catholic shrines such as the Dickeyville Grotto or the works of individuals like Howard Finster. So much of this type of art that inspires my work was created by people I’m certain I could not get along with. The tension there is interesting for me. And aesthetically, I find the cobbled together never-enough-ness of shrine-making intensely appealing. Whether that appeal is to a simple sense of taste or to something holy, I’m not sure, but I suspect there’s something spiritual there. I’m pulling on that thread.

Depending on size, your work seems to change scope; the miniatures and relief collages are Wunderkammer-like, with some leaning more towards surrealism, and your paintings retain this quality but are modeled as rococo urns. Why is that?

I’ll be really honest here. After art school, I struggled for more than 10 years to pay down student loan debt and get myself into a financial situation where I could pursue art full time. Though I’d been creating in the margins of my time, always, when I had a day job, my first real year as an artist was 2022. So I spent that year exploring a bunch of avenues at once and mixing a lot of techniques that I didn’t have time to try out before. Some of these efforts were more successful than others, and the range of work that I produced didn’t fully cohere.

The urn paintings were a way to nod to my interest in decorative arts and grottos, and I’m not sure how successful they were in this first attempt. I’ve spent 2023 tightening up my production. I’ve pulled back from the urns for most of this year, and have been working to develop paintings that are more related to my relief collages. I am planning a second round of urn paintings that will be technically and conceptually tighter, with even more of a through-line reinterpreting decorative art motifs to similar conceptual ends as my mini collages and relief collages. I’m excited to see how those will come together in early 2024.

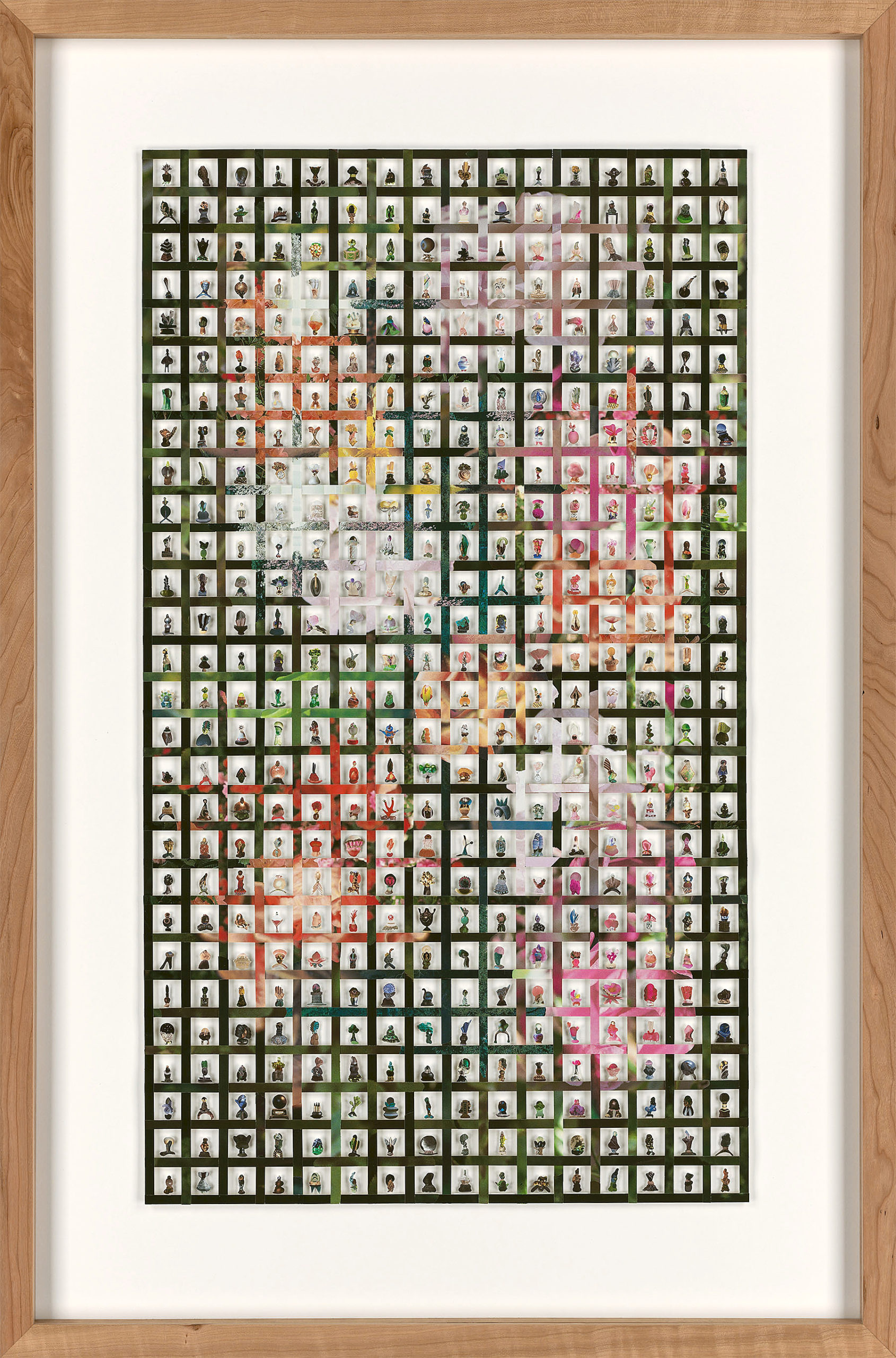

“Cathections (448),” 2023, collage relief, 35¼ by 23 inches.

How do you interrogate “the impulse to sort, catalog and assign meaning to objects?”

In my artistic process, I engage with the impulse to sort, catalog and assign meaning to objects in a manner reminiscent of a scientific researcher. I delve into artifacts, often books and magazines, extracting isolated images, colors or textures. These fragments are then carefully organized and sorted into distinct categories, much like a fossil collector creating a cabinet of specimens. I establish classifications such as “water,” “fauna” or “structure,” which become the framework for my creative game of memory and association. As I construct each individual piece, I draw connections between colors, subjects and remembered motifs.

This process, which largely occurs behind the scenes, manifests itself in the final artwork, particularly in the arrangement of my grid pieces. When viewers explore my work, they are confronted with a multitude of small paper pieces meticulously collected to form a larger image. This abundance of fragments can be overwhelming, and so the reward for close attention is to find those subtle connections I’ve made from one element to another. In this way, all of my works become shrines, evoking the essence of what shrines represent — an invitation for reflection and discovery.

[Editor’s note: For information and inquiries, www.deborahkraft.com.]

—Z.G. Burnett