(Left) Blue pinstripe suit and floral day dress. Loan courtesy of Fashion Archives and Museum of Shippensburg University. (Right) Cadillac 60 Special Sedan, 1941. Loan courtesy of the Western Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland, Ohio.

By Karla K. Albertson

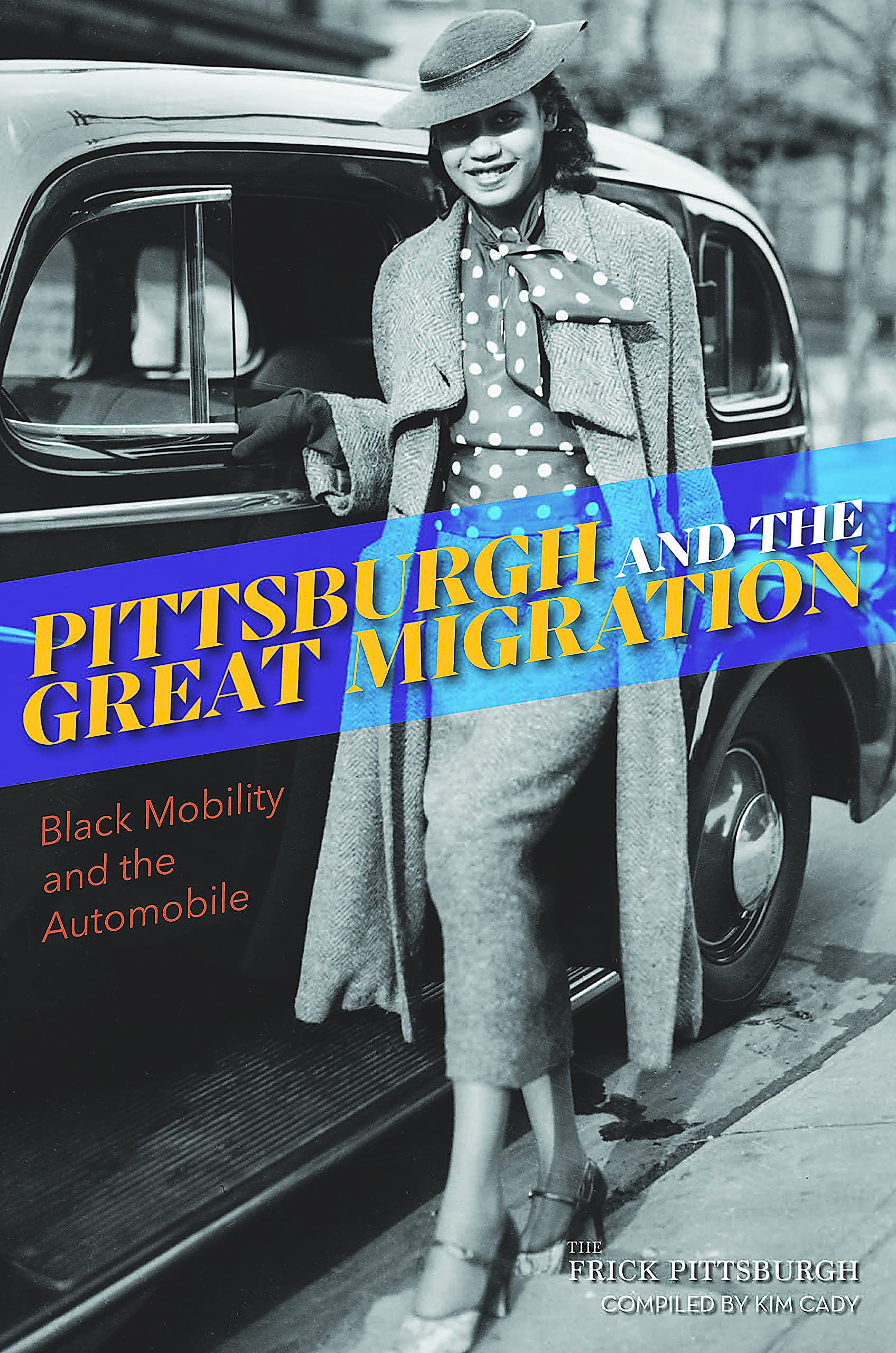

PITTSBURGH, PENN. — Rarely do exhibitions bring their central theme as vividly to life as the current long-running show at the Frick Pittsburgh. That Pennsylvania city had the industrial growth which drew an influx of workers. With “Pittsburgh and the Great Migration: Black Mobility and the Automobile,” the museum celebrates the reopening of their exceptional Car and Carriage Museum with a display of vintage automobiles, which set populations on the move, accompanied by mannequins in appropriate period costumes.

“Great Migration” is an established term for a national movement that began around 1910, gained strength during the next decade, and continued into the 1970s. African-American citizens in southern states were inspired to leave behind communities with restrictive racially based laws and attitudes and move northward seeking employment opportunities, greater financial success and political freedom. In the Midwest, Black families headed for Chicago and Detroit, St Louis and Cleveland. In the East, they traveled up to Pennsylvania and New York.

Kim Cady, former associate curator of the Car and Carriage Museum and now executive director of the Lincoln Highway Heritage Corridor, organized the exhibition. In an early interview, she said, “The great masses of people really don’t start to see that opportunity until probably about the 1920s, once more opportunities in industry become available. So, whether that’s working for Ford in Detroit as an automobile plant worker or here in Pittsburgh in the steel mills. So, once you start to see that increase in money and in opportunity to get money, you start to see more of the ownership of cars. And the car ownership really transitions the individual from kind of a lower class into a middle class because now you have this opportunity to get around, to travel at your own leisure without being restricted by bus schedules and train schedules. So, the automobile provides another sense of freedom in that sense of not having to rely on someone else nor having to deal with the harassment associated with those public transportation opportunities.”

Installation view of “Pittsburgh and the Great Migration: Black Mobility and the Automobile,” on view at the Frick Pittsburgh through February 4.

The ubiquity of automobiles today dims how miraculous the ability to go wherever you wanted seemed to early owners. Not on two feet, not packed in with others on a train. Well into the mid-Twentieth Century, families went for “a drive” as recreation in leisure hours — to get out of the city, to show off the car — just because it was now possible. The automobile also kept migrated family members connected with those still living back home and displayed the achievement of financial success.

The exhibition, which is divided into six sections, also deals with the problems encountered by Black workers who came to Pittsburgh. Arrivals from the South had different patterns of speech and behavior, different recipes and music. Many ended up living together in the same segregated neighborhoods. The influx changed Pittsburgh in a variety of visible and subtle ways.

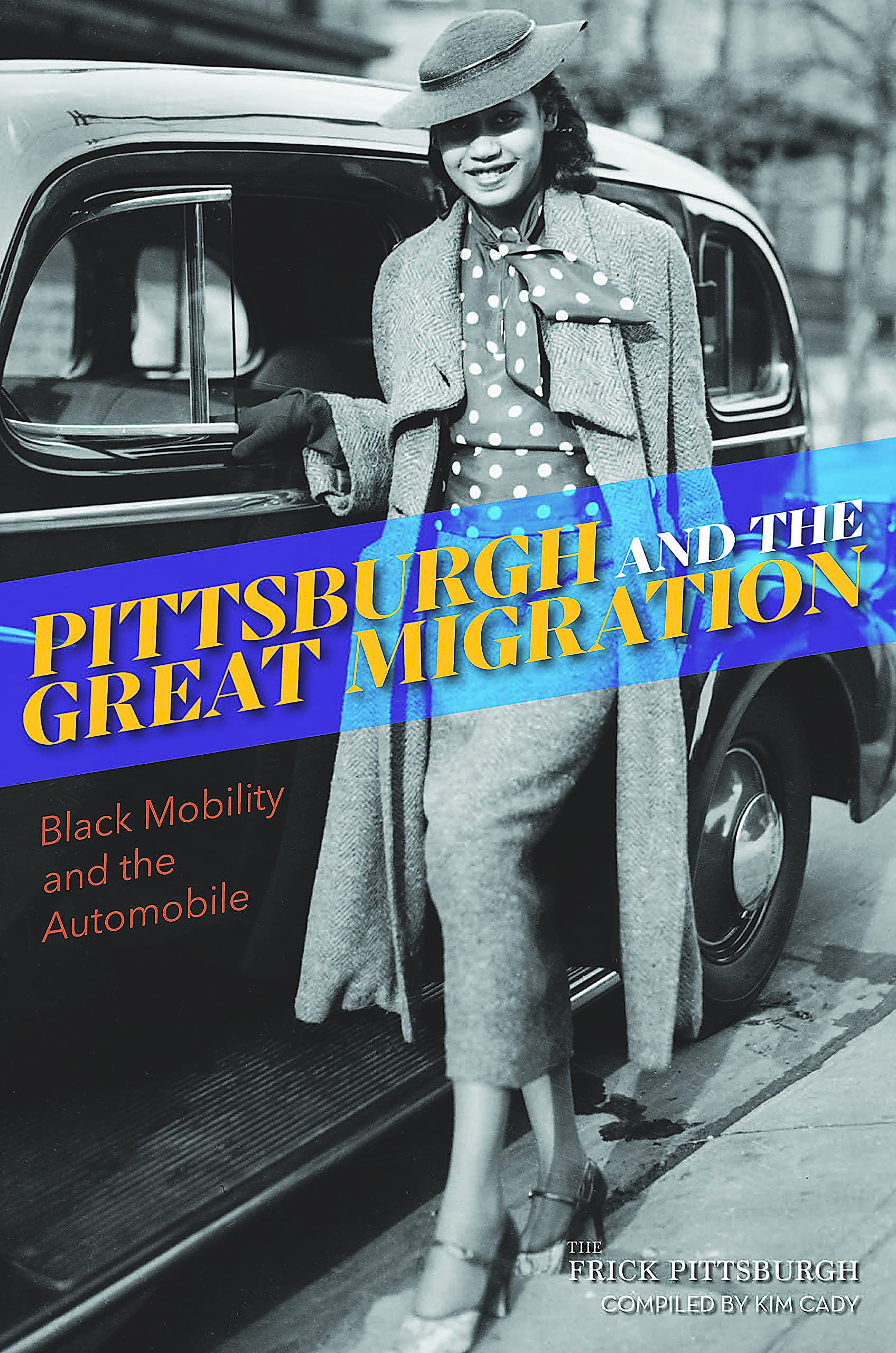

Antiques and The Arts Weekly talked with Dawn Reid Brean, now chief curator and director of collections, who pointed out that both the cars’ impact and these issues are more thoroughly explored in the “wonderfully illustrated” catalog, Pittsburgh and the Great Migration, available from the museum and through online booksellers. The museum will schedule a talk featuring the contributing scholars in the future.

Cover of Pittsburgh and the Great Migration: Black Mobility and the Automobile, compiled by Kim Cady, 2023.

She continued: “Many of our advisory panel participants were contributors to the catalog. It does an even deeper dive into the social history and the economics.”

The exhibition’s advisory panel members included: Ron Baraff, Rivers of Steel; Samuel W Black, Heinz History Center; Elizabeth A. Burns, The Burns Collection & Archive; Charlene Foggie-Barnett, Teenie Harris Archive, Carnegie Museum of Art; Laurence A. Glasco, PhD, University of Pittsburgh; Jonnet Solomon, National Opera House; and Gretchen Sorin, PhD, Cooperstown Graduate Program, State University of New York; Joe William Trotter Jr, PhD, Carnegie Mellon University; Mark Whitaker, author and journalist.

Part of the unique character of the Frick Pittsburgh is its Car and Carriage Museum. According to the curator: “It’s the biggest exhibition we have ever staged in those galleries, which has been part of the excitement around the show.” Two of the earliest cars in the show are from their permanent collection: the Lincoln Model L, 1922, and the Ford Model T Touring, 1914; both came from the William P. Snyder III collection, given to them in the 1990s. Others were loaned by the Western Reserve Historical Society in Cleveland, such as the 1949 Chevrolet 3100 GP Pickup Truck.

Chevrolet 3100 GP Pickup Truck, 1949. Loan courtesy of the Western Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland, Ohio.

The visual impact is completed by the presence of period costumes within the automobile and mannequin tableaux of the exhibition. Brean explained that many are on loan from the Fashion Archives and Museum of Shippensburg University in Shippensburg, Penn., “They have a very deep collection of everyday garments.” Thus, the figures illustrate the auto’s utility in everyday lives as they moved families to work and leisure.

“Pittsburgh and the Great Migration: Black Mobility and the Automobile” will enjoy a long run from its opening early last May to February 4, and the curator commented on the reaction of visitors so far: “We have a lot of people who love Pittsburgh, who are visiting the city or who are invested in Pittsburgh history. And so many people coming on the tours say they never knew this chapter of Pittsburgh history or even American history. They didn’t realize how much our city had been shaped by the Great Migration, by the influx of Black Southern migrants to the city of Pittsburgh. So, it’s an aspect of our history that’s been somewhat hidden. And, of course, we’ve had people connecting with the show on a more personal level, people who have been sharing their stories with us and other visitors in gallery conversations.”

When asked if Pittsburgh was more affected by the movement than other eastern cities, she replied: “I think it was. I think the steel industry offered a certain economic promise to a lot of people who were looking for better jobs. There was a lot of industry and available jobs and opportunities that were drawing people here. On the job circuit, it was an important stop between New York and Chicago. It was a uniquely positioned city for the Great Migration.”

The Frick Pittsburgh is at 7227 Reynolds Street. For more information, 412-371-0600 or www.thefrickpittsburgh.org.