Cylinder vessel with solar deities, Guatemala, Petén, Naranjo or vicinity, 650-850 CE, slip-painted ceramic, 6-3/8 by 3-3/16 inches. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Purchased with funds provided by Camilla Chandler Frost.

By James D. Balestrieri

AUSTIN, TEXAS — After having been on exhibit at several museums in China in 2018 and 2019, the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas at Austin will be the sole venue in the United States to present “Forces of Nature: Ancient Maya Art from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art,” on view from August 27 through January 7. It’s a shame that “Forces of Nature” only overlaps for a few days with the equally wonderful “Lives of the Gods: Divinity in Maya Art,” which opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, moved to the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth on May 7, and closes there on September 3. A three-hour drive divides the two. Visits to both exhibitions would provide a pretty thorough immersion into the always fascinating world — or worlds — of the Maya. Both exhibitions focus on the Classic period (250-900 CE) but extend their explorations back to the origins of the Maya millennia earlier. Both also discuss the endurance of Maya peoples, languages, culture and customs to the present day. Where “Lives of the Gods” takes a deep dive into the myriad Maya divinities that create and explain the world we inhabit, the thesis of “Forces of Nature” goes into greater detail about the relationship between divinity and divine right, and the pictorial and ceremonial uses rulers made of the pantheon of gods that governed the Maya cosmos.

The Maya flourished in what is now southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, Honduras and parts of Nicaragua and Costa Rica. A loose confederation of city-states as opposed to an empire, they were united by a common written language comprised of complex ideograms and a highly refined cosmology that found expression in diverse artforms. Every aspect of Maya life was infused with deity. Ornately decorated ceramics, exquisite jadeite pieces and figurative whistles tell Maya stories of origins, generation and transformations. The ballgame, a ritual rather than a sport, connected the temporal world with the spiritual. And, of course, the monumental Maya pyramids reproduced mountains and hosted caves that mimicked the apertures of creation, often represented as the maws of centipedes.

Teotihuacan-style censer with Ancestor and Storm God, Guatemala, Escuintla, 300-600 CE, ceramic with post-fire pigment, 11 by 9 by 9-3/8 inches. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Purchased with funds provided by Camilla Chandler Frost.

The exhibition is divided into four parts, perhaps in homage to the four directions — plus the sun in the center — that delineate the Maya universe. An “Introduction” offers an overview of the history and culture of the Maya. “Supernatural entities of Sky, Earth, Water and Underworld” give an overview of Maya cosmology. “Animals in Maya Art and Religion” show the Maya view of nature and animated and anthropomorphic. Lastly, “Divine Rites of Kings and Queens” finds the rationale for authority in the Maya rulers’ ability to transform cosmology into ceremony.

Numerous images of solar deities, for example, depicted on cylinders that suggest visible and invisible realms — what is revealed and what is hidden — incarnates the sun as young and old, as a shark, a jaguar, a disembodied head or a seated ruler. A portable pantheon, “Cylinder Vessel with Solar Deities,” created circa 650–850 CE, as exhibition curator Megan O’Neil states, “may mark the changing of the seasons… the bound and burning Jaguar God of the Underworld [the nocturnal sun] may personify the annual transition from the dry to the wet season” (cat. p. 80).

Two key aspects of Maya aesthetics arise from a work like “Cylinder Vessel with Solar Deities.” The first is motion: worlds in motion. Rotating this cylinder, or any of the many such objects that still exist, conveys not only a sense of time, but also the fluidity of the realms, and of the beings that inhabit them. Add the text at the top of the cylinder and you approach something close to a silent film — which would almost certainly have been anything but silent to those who could read it. The second is the sinuous lines, forms morphing into forms, that characterize Maya art. In Maya art, and one suspects, Maya culture in general, identity and being were — and perhaps still are — rarely straightforward affairs. Paths wind, like destinies. Humor and pain, in Maya imagery, often seem inextricably bound to one another, cartoonish and calligraphic to our Western eyes. We know a great deal about the Maya calendar, but the Maya sense of time — or, better, being and seeing in time — must have been nothing short of extraordinary.

Mortuary panel, Guatemala or Mexico, Petén or Chiapas, vicinity of Piedras Negras, 687-800 CE, limestone, 22½ by 22 by 4 inches. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Anonymous gift.

The mystery of Maya cosmology is that we simply don’t know all the actual names of the gods, or their manifold and fluid functions. The destruction of the original Maya codices by the Spanish after their conquest, the incomplete nature of the four extant post-colonial codices, and the ongoing evolution of Maya spiritual practice in the intervening centuries has meant that some of the religion of the Maya may be forever lost. Still, in the cylinders and other objects such as the remarkable “Carved Box with Deities,” executed circa 450-550 CE, the intertwining and repetition seem to replicate the overlapping, sinuous links between realms, while the vertical lines suggest separation in the manner of sequential art. At right, for example, a god known only as God L, wears a jaguar skin and large feathered headdress. He smokes a cigar and holds a lance. He is not young and seems to lean in to the scene with a certain pugnacity and air of experience. I realize I could be projecting, and that projection might be dangerous from an anthropological/art historical point of view, but the fact is that the figures on Maya artworks are striking in terms of personality, something you rarely see in other ancient cultures. Despite their deity, their depictions offer very human ways in for contemporary viewers. Perhaps the best analog I can think of is Japanese woodblock prints. Indeed, as the exhibition texts stress, it is impossible to tell, at times, whether what we are seeing is a portrayal of a deity or an impersonation of a deity by a member of the nobility.

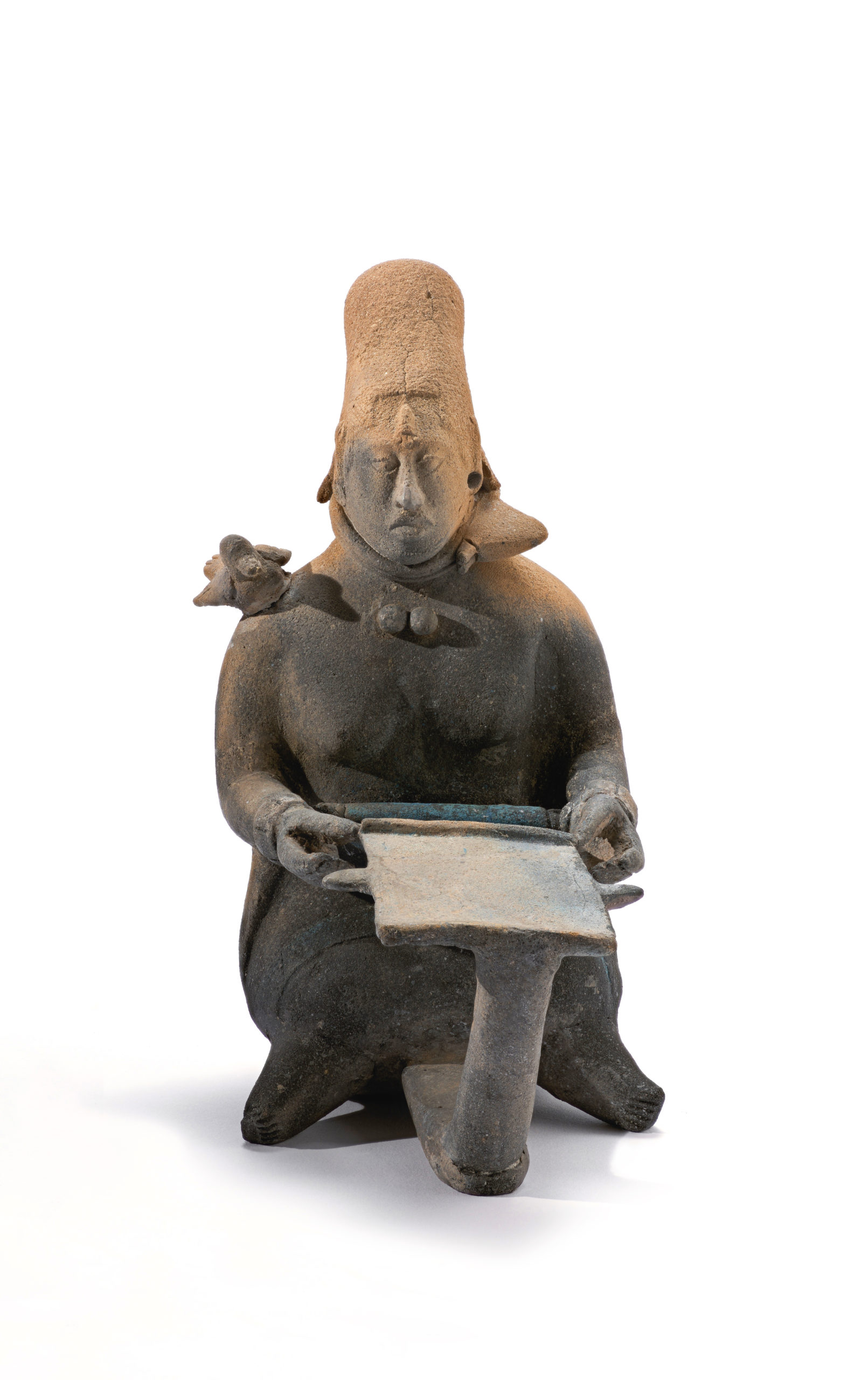

Animals of earth, air and water feature prominently in Maya cosmology and philosophy. For the Maya, the world rested on the back of a turtle or crocodile. Monkeys, for example, were seen as the gods’ first drafts for human beings. They partake in human activities, sometimes humorously, and are also portrayed as scribes, perhaps as caretakers of memory. In “Plate with Supernatural Monkey,” circa 600-900 CE, one sees an anthropomorphic affinity between the Maya simians and China’s Monkey King, one of the principal protagonists in the spiritual allegory, “The Journey to the West,” or the many African tales that cast the monkey as, among other roles, custodian of the ancestors. Human scribes, artists, and artisans were revered among the Maya, and “Figurine Whistle of a Woman with a Backstrap Loom,” circa 600-900 CE, offers insight not only into weaving, but into the place and status of women in Maya society. Maya women were depicted in typical maternal roles — and as gods — but also in scenes where they participate in various occupations. The exhibition suggests that the evidence is scant, but this would seem to be a fruitful area for future exploration.

Plate with supernatural monkey, Guatemala, Petén, 600-900 CE, slip-painted ceramic. Los Angeles Museum of Art. Purchased with funds provided by Camilla Chandler Frost.

Rulers often donned feathered headdresses and clothing, associating themselves with the powers of creatures that could fly. Water was a liminal space, filled with stylized, hybrid beasts that connected World and Underworld.

The Maya also personified forces of nature such as rain, which included lightning, thunder and storms of every kind. The name for the rain god was Chahk. The various incarnations of Chahk would have been appeased and summoned with objects such as “Teotihuican-style Censer with Ancestor and Storm God,” circa 500-600 CE. Inside an angry Chahk mask — the symbol at bottom looks an awful lot like lightning — a figure peers, holding what may be a torch. Smoke from the censer would have issued from the mouth of the deity, obscuring the face of the ancestor in a spectral haze. The Maya who wielded this censer might very well have projected power as well in a priestly or shamanistic role.

Despite its small size, “Whistle with Ruler, Bicephalic Serpent, and Ballplayers,” circa 600-900 CE is a stunning object. Here, a ruler stands on an elaborate throne between two serpents, indicating his authority, and perhaps, powers of transformation. At the bottom, ballplayers are engaged in a match that would have been played with a rubber ball that contestants would try to get through a ring attached to a wall on a long court. The ballgame was associated with the Hero Twins, players who appear in the Popol Vuh, one of the seminal Maya texts. The Hero Twins’ game against the Lords of Xibalba — the Underworld — was played to secure the cycles of growth and renewal and Maya who earned the sobriquet “ballplayer” would be counted among the elite. The court was a portal to the Underworld and the game and attendant rituals — dancing and music, hence the whistle form — may have offered spectators a kind of immersive and transubstantiative experience of the Hero Twins’ athletic, mythical trial, one they would lose, only to be reborn. Again, imagining one of these ball games conjures fluid images of constant movement, sound and spectacle.

Whistle with Ruler, Bicephalic Serpent, and Ballplayers, Guatemala, Petén, 600-900 CE, ceramic with post-fire pigment, 2¾ by 6-4/5 by 3 by 4 inches. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Purchased with funds provided by Camilla Chandler Frost.

This concept of fluidity is something that is overlooked in the Greco-Roman heritage of the Western tradition. We think of Athena as the Greek goddess of wisdom and war. In fact, in terms of war, she is the goddess of strategy and prudence. She is also the patron of household arts and crafts and weaving, having entered into a fateful contest with Arachne that ended with Arachne becoming an arachnid, a story that sounds almost Maya. Local cults combined Athena with their own deities. She often appears as an owl or sea-eagle. Her origins may date back to early Near Eastern warrior goddesses — Ishtar and Inanna. Evolution and adaptation. The sinuous lines between one incarnation and another. Rebirth on top of rebirth. That we limit the Greek and Roman deities in two or three major roles is more a function of popular culture — I’m looking at you, Percy Jackson — than of a true understanding of the saturation of the supernatural in Ancient Greece and Rome. While perhaps unintentional, “Forces of Nature” might just nudge us to reassess our relationship with nature in the Western world. If we did that, we might also reassess our responsibility to nature, and to one another.

The Blanton Museum of Art on the campus of the University of Texas, Austin, is at 200 East Martin Luther King Jr Boulevard. For information, 512-471-5482 or www.blantonmuseum.org.