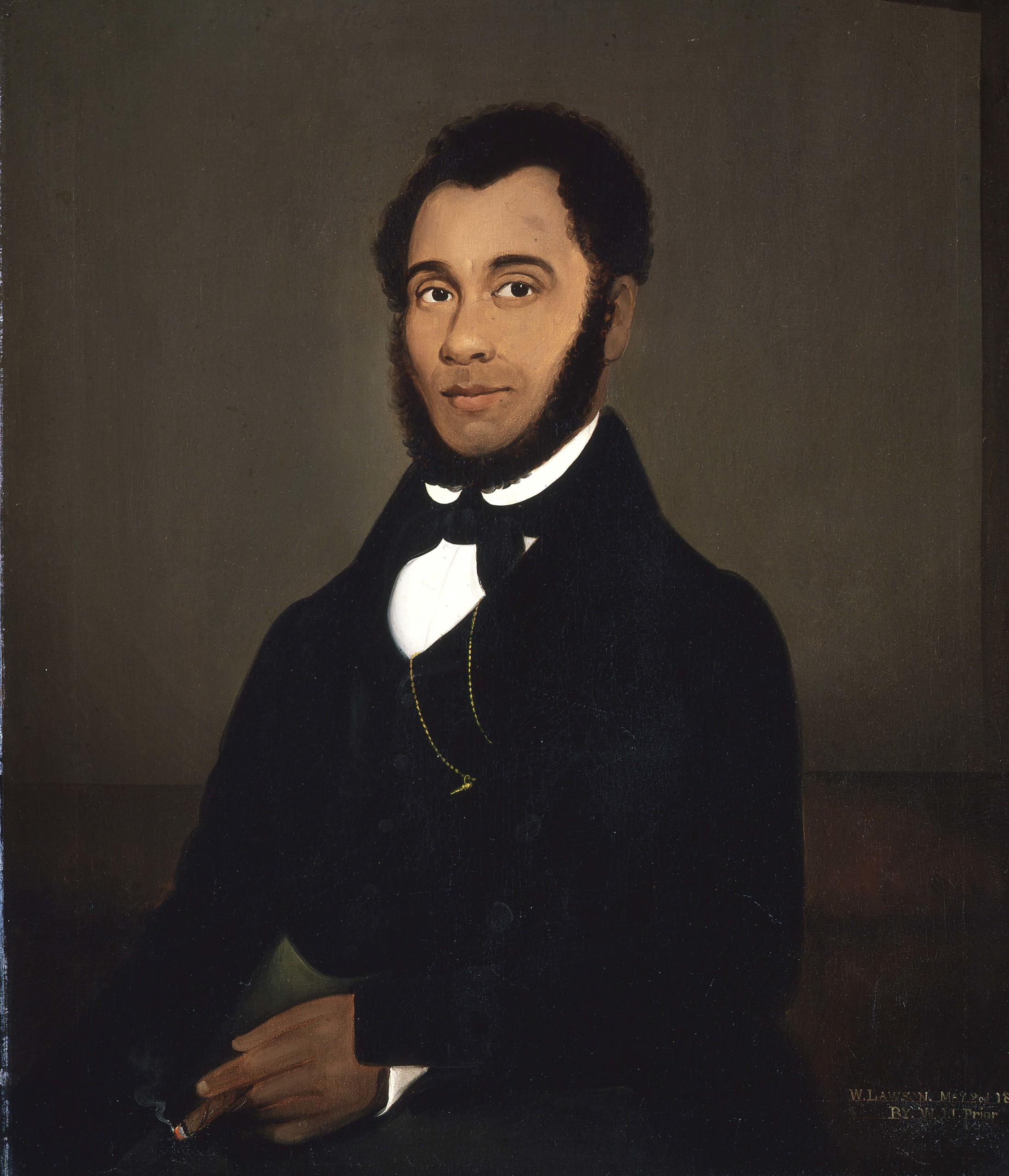

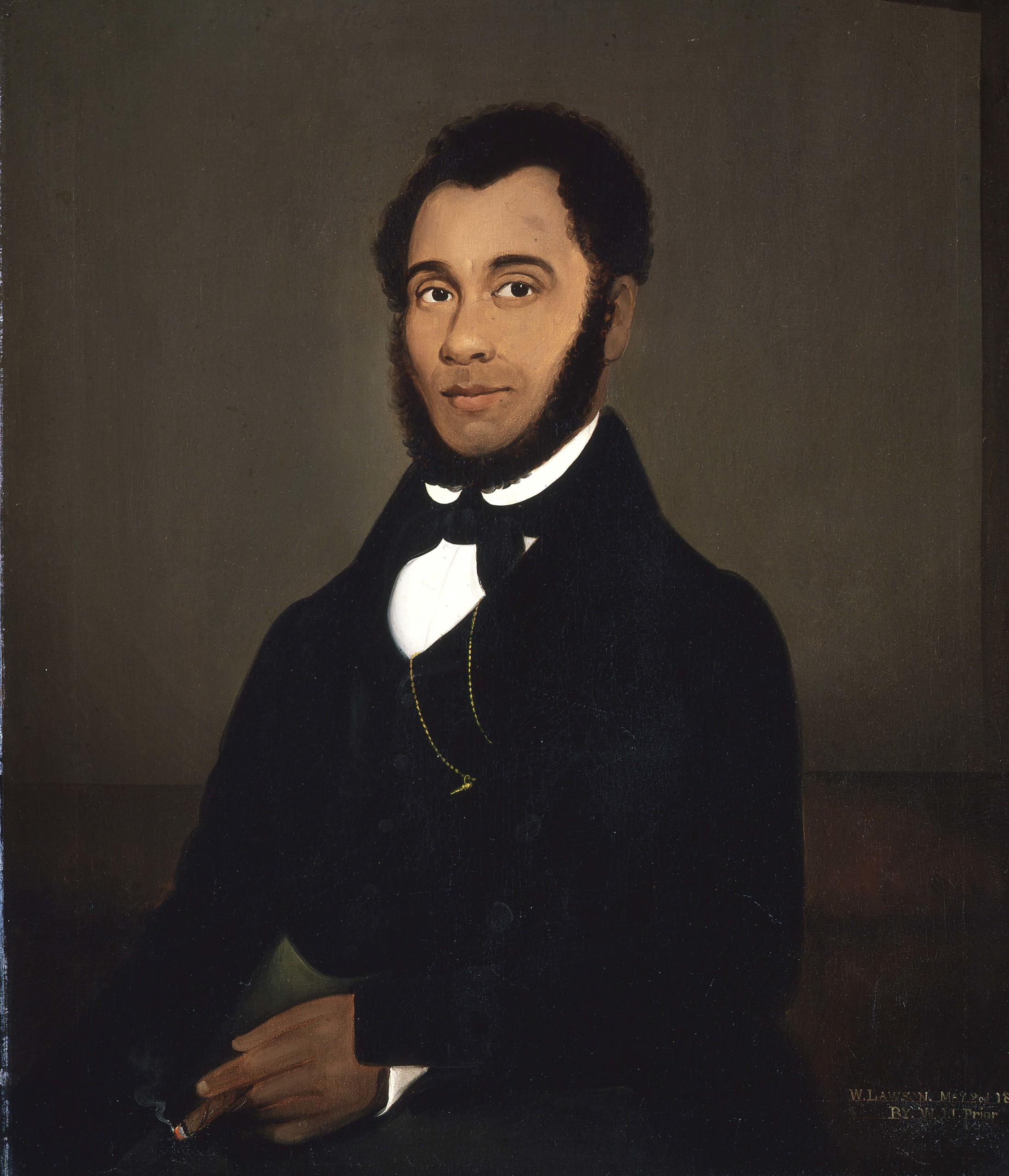

“Nancy and William Lawson” by William Matthew Prior, 1843, oil on canvas, Shelburne Museum, museum purchase, acquired from Maxim Karolik, 1959, Andy Duback photos. Moving from the margins to the centers of paintings, this pair of portraits of Bostonians Nancy and William Lawson paints Black sitters on “distinctly white terms,” which Emelie Gevalt argues “demonstrates ongoing conflicting attitudes in white New Englanders’ relationships to their Black neighbors.”

By Madelia Hickman Ring

NEW YORK CITY — The newest exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum (AFAM) trains a bright light at Black figures — represented throughout the art historical canon — who because they are rarely identified by name, are simultaneously present and absent. Examining American folk art under a magnifying lens of race, the museum explores the stories of persons whose identities have been lost to history.

The timing of “Unnamed Figures: Black Presence & Absence in the Early American North” is prescient, opening when museums are looking to reinterpret their permanent collections and reveal more diverse stories hidden within. It is curated by Emelie Gevalt, AFAM’s curator of folk art, with Dr R.L. Watson, assistant professor of English and African American Studies at Lake Forest College, and Sadé Ayorinde, the AFAM Warren Family assistant curator.

“The museum is especially well-positioned to tell this story because of the special knowledge we have of forms that have historically been marginalized,” Gevalt told Antiques and The Arts Weekly, when we asked her why the AFAM was the right venue for the show. “A lot of folk art shows center around promoting folk art as a concept; it isn’t that kind of a show but rather draws on objects that might be considered folk art to tell that story.” The curator continued, “We have a broad range of material — plainer style portraits, needleworks, works on paper, stoneware, overmantel panels — which are all what are considered core folk art forms but not necessarily ones that have found themselves center stage.”

Additionally, the show builds on Gevalt’s doctoral dissertation, which looked specifically at Eighteenth Century interiors and the depiction of African American figures on overmantel panels, needleworks, wall paintings and portraits.

“Abraham Hanson” by Jeremiah Pearson Hardy (1800-1888), Bangor, Maine, circa 1828, oil on canvas. Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Mass. Museum purchase, 1943. Bangor, Maine, resident Abraham Hanson was a barber, a respected profession in the Black community. The artist did not paint the portrait for Hanson’s ownership but rather to advertise his skill at painting sitters of varying skin colors.

The eponymous publication that accompanies the exhibition is not a typical catalog per se; rather, it is a compilation of several essays and shorter studies on a variety of themes the exhibition addresses. The choice of this, Gevalt says, was to show the range of scholarship employed in the show’s creation.

Art historical interest in the representation of Black figures is not new; it began in 1916 with Freeman H.M. Murray’s Emancipation and the Freed in American Sculpture: A Study in Interpretation. By the 1970s, museums in the United States were actively buying, borrowing or moving out of storage images of Black people. While this trend might be considered a positive step, because supply could not meet demand, it created a market for faked portraits.

The book’s foreword drives this point home in a cautionary tale. It was written by Gwendolyn Dubois Shaw, who tells the story of a portrait attributed to Ethan Allen Greenwood (American, 1779-1856) of Charles Jones, who was the supposed son of Absalom Jones (1746-1818), the first African American to be ordained as an Episcopal priest. Shaw learned of the portrait while she was curating an exhibition on Black portraiture. Long story short, soon after the portrait graced the cover of the Addison Gallery of American Art’s catalog for its 2006 exhibition, “Portraits of a People: Picturing African Americans in the Nineteenth Century,” she discovered that the name of the sitter was, in fact, fictional: Greenwood had never painted anyone from the Jones family and Absalom was recorded as never having had children. Additionally, the painting revealed, through scientific analysis, that the face of the sitter had been doctored, which she describes with the term “Blacked-up.”

“Perry Hall” by Francis Guy (1760–1820), Perry Hall, Md., circa 1805, oil on canvas. Maryland Center for History and Culture, Baltimore, Mrs Drayton Meade Hite Purchase Fund in memory of her husband, 1990. This landscape painting of Perry Hall is one of a suite of several that co-curator Emelie Gevalt’s early scholarship and research focused on. Though the identity of the Black groom included on the far left of this painting is unknown — and it could refer to a trope rather than a specific individual — there were several men and boys listed among the property of the Goughs who owned Perry Hall.

Gevalt presents, by way of her introduction and a painting that was one of several to inspire her doctoral research, a late Eighteenth Century Maryland School oil on canvas landscape that depicts the house and property of Perry Hall. Several figures and animals are represented within these images; the identity of all of the white people in the painting are known but not the Black ones. Their presence, Gevalt argues, belies the “peace” of the pastoral scene and begs viewers to acknowledge her as more than simply “an accessory to powder…a symbol that elevates the status of the primary, white subject.”

A longstanding assumption — one centered around a whitewashed history of New England, is that there was no history of slavery in New England. One of the goals of the curatorial team was to counter that mythology by presenting in visual form that, in fact, quite the opposite was true.

While the exhibition includes some images of early African Americans deemed important enough to warrant representation in print or painting, it makes no attempt to comprehensively catalog all Black representation in the early American North. Rather, a greater attempt has been made to “those historically unidentified or even fictional, the anonymous ‘servant,’ the ancillary figure in the background, bodies whose everyday labors gave shape to the fabric of colonial and later American life.”

Three primary sections organize the exhibition itself: “Presence and Absence,” “Early Black Makers” and “Remembering, Misremembering and Forgetting.” In the first, the essay writers register Black absence through an exploration of limited Black presence in surviving art and material culture and outlines a framework for the realities of Northern slavery. Works by early African American authors and an analysis of a Rhode Island overmantel panel further establish a methodological template with which to critically consider objects in the show.

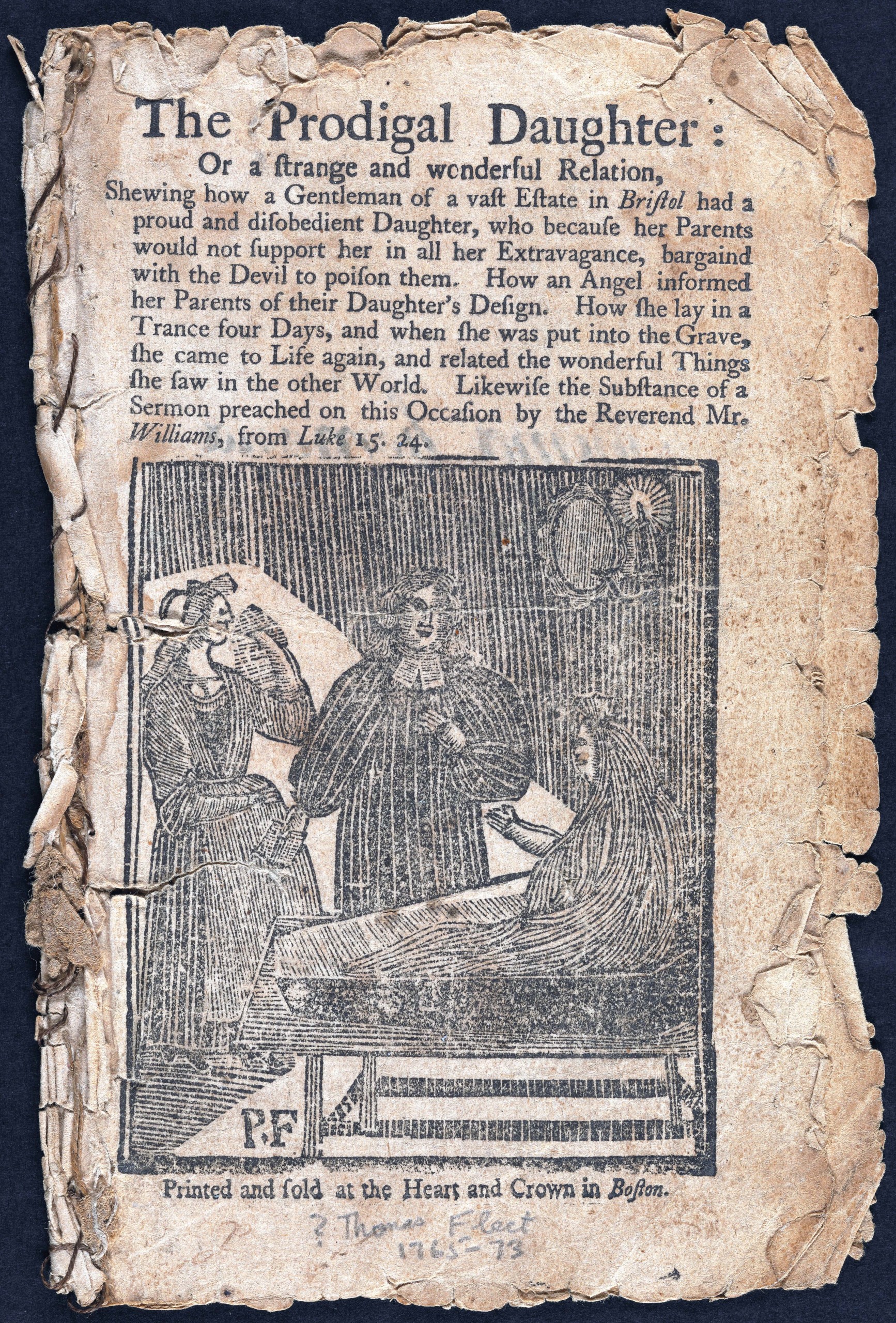

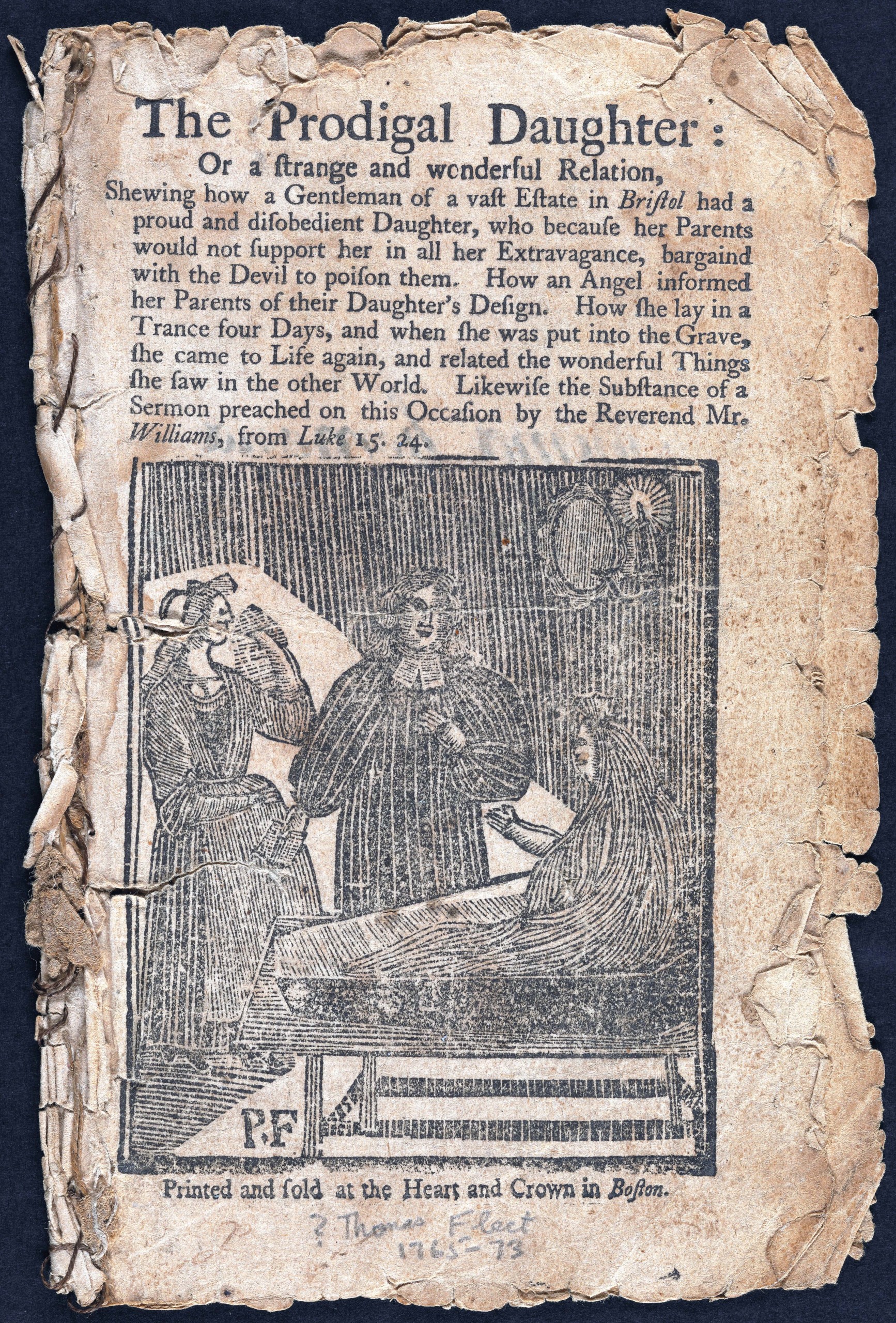

Frontispiece from The Prodigal Daughter, illustration attributed to Peter Fleet, Boston: Thomas Fleet, 1736; reproduced by Nathaniel Coverly Jr printer, Milk Street Boston, 1810, woodcut. Princeton University Library Special Collections. Black printer Peter Fleet (active 1733-1758), who was enslaved to Boston newspaperman Thomas Fleet (1685-1758) created several woodcuts, including a 1736 moralizing pamphlet titled The Prodigal Daughter. In the leaflet, the Devil — in the form of both a White gentleman and a Black horned figure — counsels a “proud and disobedient” young woman; it equates “light” and “dark” with “good” and “evil.”

Surviving objects by Black makers provides an essential opportunity for examination of Black creativity and production. Peter Fleet’s illustrations for The Prodigal Daughter, portraits by Joshua Johnson (American, circa 1763-1824), long considered the first professional Black portraitist in the United States, stoneware made in New York City by potter Thomas W. Commeraw who traveled to Sierra Leone and samplers worked by Black needleworkers in Connecticut are featured in the second sections.

The third section, an analysis of “Darkytown,” a Nineteenth Century painting and its later reimagining by contemporary Black artist Kara Walker (b 1969), Black imagery in daguerreotypes and cartes de visite, “doctored” Black portraits and the issue and ethics of retitling works try to untangle the web of Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Black history with later memory- and mythmaking.

Discoveries and revelations made themselves known to the curators in the course of pulling the exhibition together. Initially expecting to find little in the way of surviving objects, Gevalt said, “This history is everywhere, you just need to look more persistently.” The museum was able to connect with descendants of figures or communities represented in the show; some of those have been captured in an audio recording that is included in the show.

Two-gallon jar made by Thomas W. Commeraw (circa 1771-1823), New York City, circa 1797-1819, salt-glazed stoneware with cobalt decoration. Private collection. Thomas W. Commeraw is the earliest known Black potter working in New York City; his salt-glazed jars were supplied to the oyster trade.

The issue of race is a complex, difficult one that the curators hope visitors are willing to confront. “We want to propose that by asking questions, people can move forward even with discomfort. Some of these objects are really complex; there can be representations that were meant to be respectful that can also have an underlying racist visual vocabulary; it’s something that needs to be carefully considered,” Gevalt said.

Gevalt is clear about what the exhibition intends and what it achieves. “On a broader level, we are asking visitors to do more work, to ask critical questions, even about things as straightforward as a title. We invite visitors to imagine alternative histories that might not be directly represented. But we know we won’t have all the answers.”

“Unnamed Figures: Black Presence & Absence in the Early American North” is on view at the American Folk Art Museum through March 24. It will subsequently be on view at Historic Deerfield from May 1-August 4.

The American Folk Art Museum is at 2 Lincoln Square. For information, 212-595-9533 or www.folkartmuseum.org.