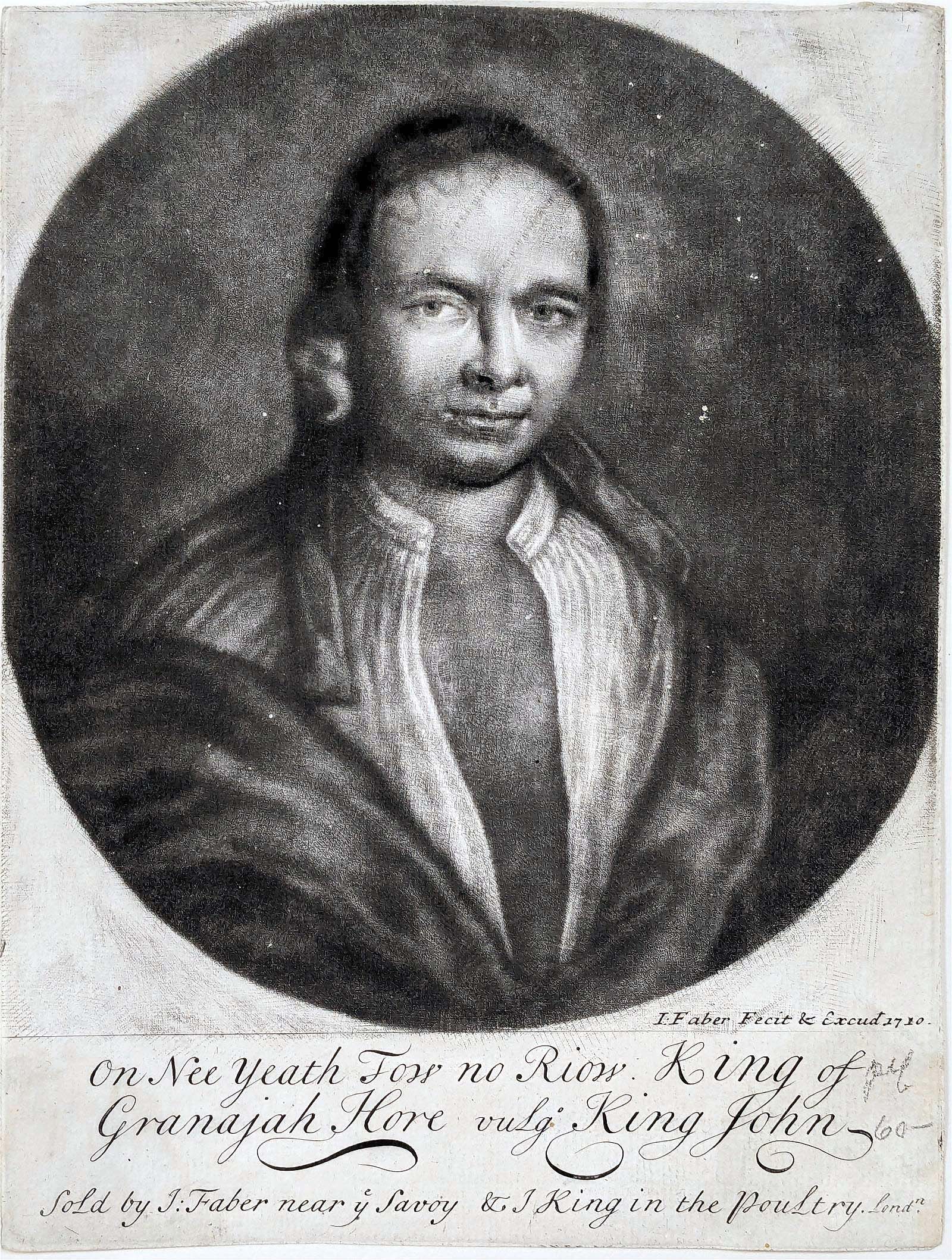

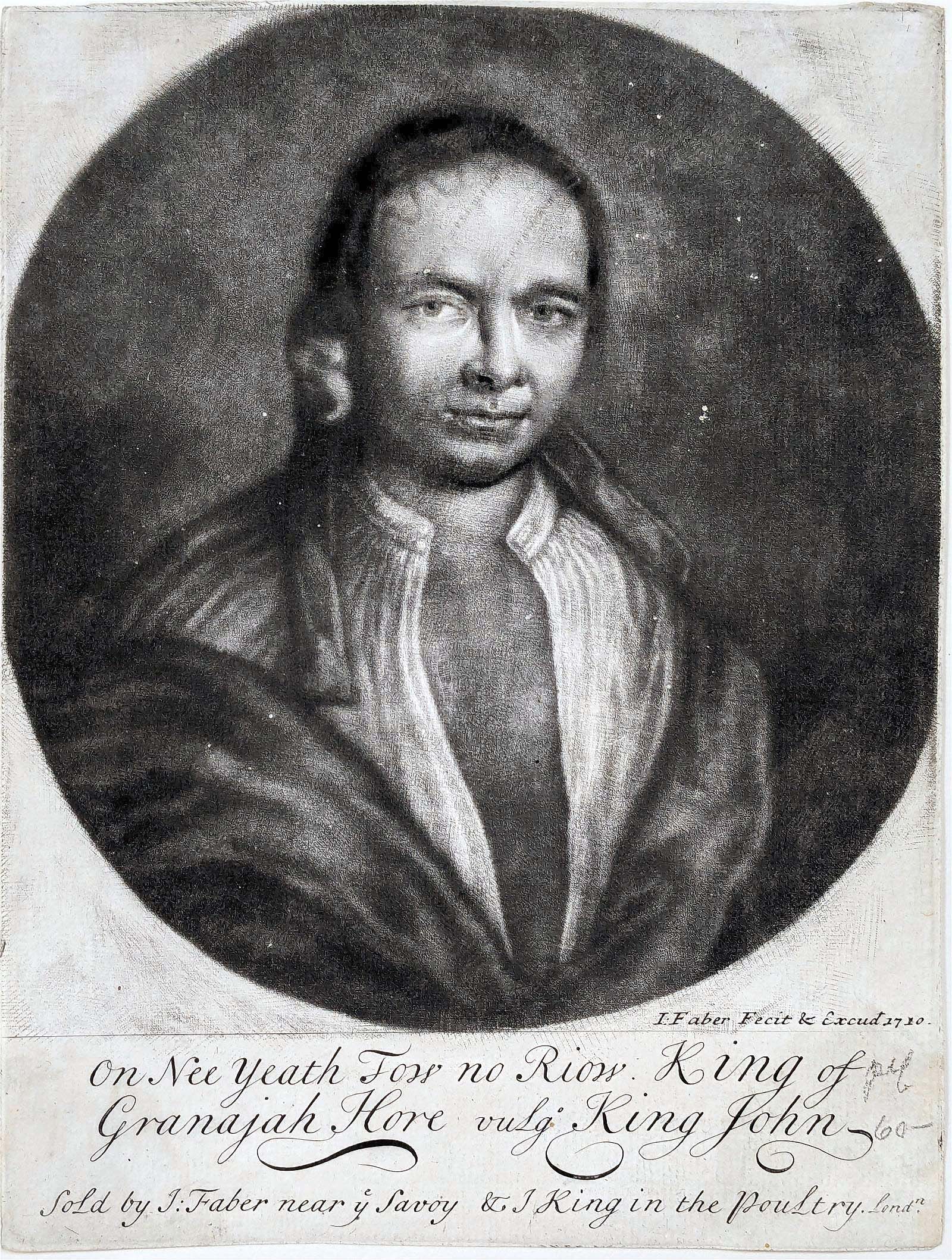

As expected, the sale’s highest price, $36,830 was realized for this 1710 mezzotint by John Verelst, “On Nee Yeath Tow No Riow.” It sold to a trade buyer, on the phone, underbid by an institution.

Review & Onsite Photos By Rick Russack; Catalog Photos Courtesy Tremont Auctions

SUDBURY, MASS. — On February 25, Tremont Auctions offered more than 200 lots of early prints, drawings and engravings from the collection of Winfield Robbins; the sale earned more than $341,000. Some prints were sold individually, and some were grouped with multiple pieces. Only two prints remained unsold after some post-sale activity. It was the final installment of a collection that Tremont began selling in 2023.

Until recently, the entire Robbins print collection was housed in the Robbins Library in Arlington, Mass., in an Italian Renaissance style building built with funds from an 1892 gift from the widow of Eli Robbins. The background of the collection is fascinating. Winfield Robbins, a nephew of Eli, had a passion for preserving history, especially portraits of historical persons, some famous, some not so famous. He believed that, in order to teach history properly, students should be able to see images of people they were learning about. He not only collected engravings dating back to the Fifteenth Century, traveling extensively in Europe to do so, but he also collected prints and photographs of prominent personalities of the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries. The result of this passion was a collection, that, although it included Old Master prints by Rembrandt and Durer and some genre scenes, it was mostly of portraits, and that totaled far more than 150,000 pieces. Robbins carefully matted many images and preserved all in archival print storage boxes. How many boxes? More than 2,000!

Prints were displayed throughout the gallery for inspection during the preview.

Starting in 1893, Robbins donated portions of his collection to the Arlington library. In 1901, he donated framed portraits intended to, as he said at the time, “illustrate the progress of the art of engraving.” When Robbins died in 1910, he left the collection — at that time about 120,000 prints — to the library along with $25,000 “to care for and increase my collection.” Between 1910 and 1949, his cousins, Ida and Cara, continued to add to the collection. When Ida died in 1949, she donated an additional 30,000 prints and an additional $30,000 “in trust for the prints” to the library.

The total of about 150,000 prints were available for public viewing and study in the library, which took good care of them. Many were hung in the library, and many were used in periodic exhibitions in the building. Others were loaned to institutions. But eventually the library trustees, understanding the importance of the collection, and concerned about the cost of maintaining it, were faced with determining whether or not they were proper custodians for it. They also took into consideration the low number of interested members of the public that utilized the collection. All signals pointed toward considering the disposal of the collection. One of the difficulties was that it had never been completely indexed, it was just divided into three major sections: American prints, European prints and Japanese prints. In 1978, the position of curator was abolished. In the 1980s, several professionals, from such institutions as Harvard University and the Boston Public Library, and, later, other knowledgeable appraisers, were consulted about how best to dispose of the collection. No suitable, definitive answers were forthcoming. The collection was simply too large, and the time and effort required to properly identify and properly index it were not feasible. Since the library was a part of the town of Arlington, the approval of the voters was required to dispose of it and, in 2019, a warrant article was approved to allow the library trustees to proceed with deaccessioning the collection and a collections management firm was retained. Then the pandemic came along.

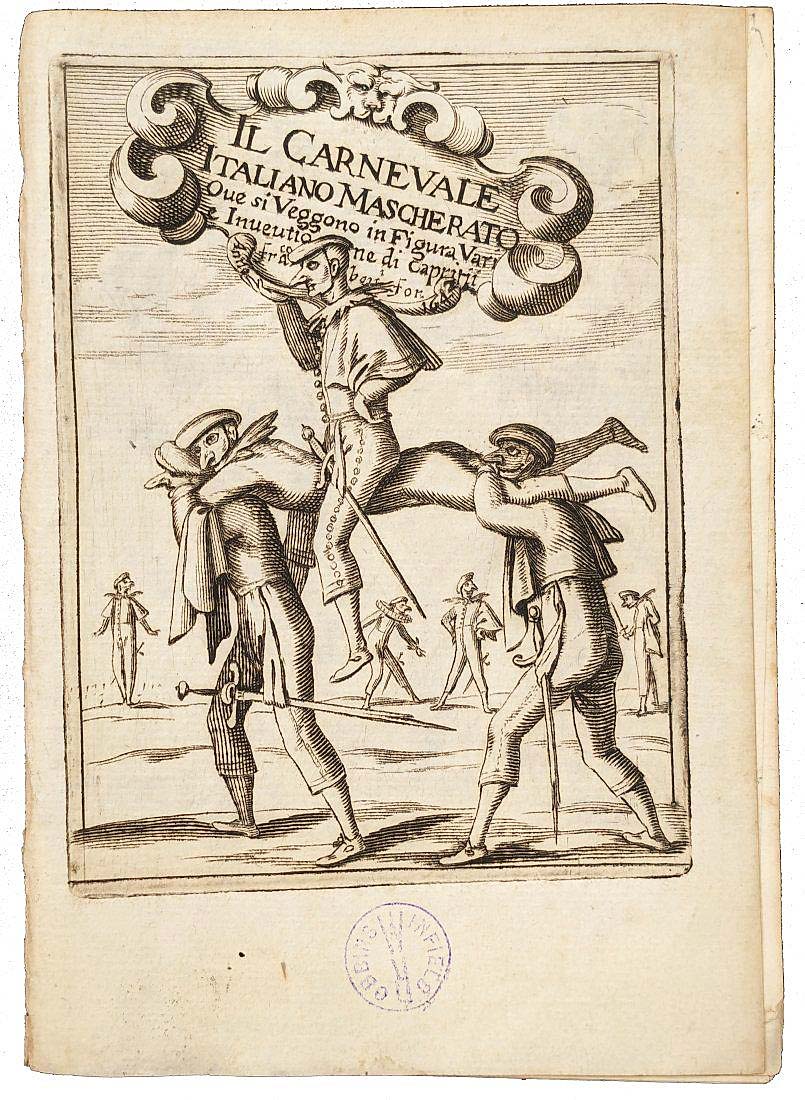

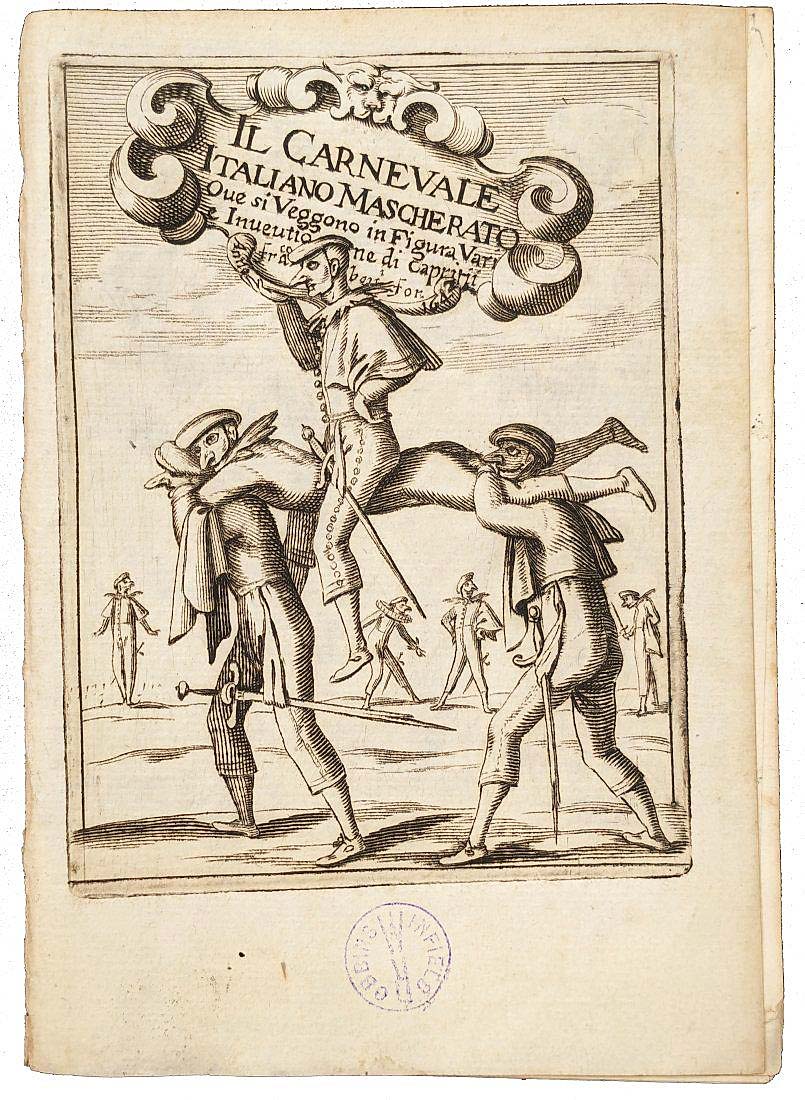

A series of 25 engraved plates with captions by Francesco Bertelli showed masked figures in costume for the masquerade at Venice’s carnival, Il Carnevale Italiano Mascherato. Done in 1642, it went out at $5,208.

In 2022, through connections with another auctioneer, Brett Downer of Tremont Auctions was contacted; he and his staff spent days going through each of the 2,000 storage boxes. They, with the assistance of knowledgeable professionals, including Jim Bergquist, selected a small group of prints to auction on behalf of the library. The successful sale last year led to this sale. But the problem remained of what to do with the huge number of remaining prints, still more than 150,000. Downer discussed the collection with a New Hampshire antiques dealer who took a gamble and bought the collection. That dealer commented recently to this writer, “I have over 2,000 boxes of prints (which we saw) and I haven’t even opened more than half the boxes yet. I’m slowly learning about them and getting some of my money back.” So, without a doubt, the story is ongoing.

The most sought-after lot in this sale was a 1710 mezzotint portrait of a Mohawk chief, which earned $36,830. It depicted On Nee Yeath Tow No Riow, who was one of four chiefs — three Mohawk and one Mohican — who traveled to England to seek Queen Anne’s military aid in combatting the French forces in the Great Lakes region. She commissioned John Verelst to make paintings of each of the four chiefs. A small number of mezzotints from these portraits, including this one, were created by John Simon. The original paintings are owned by the Portrait Gallery of Canada. This mezzotint was thought to be the scarcest of the ones in the Robins collection, as there were no previous auction records of it. It was bought by a dealer, on the phone, underbid by an institution.

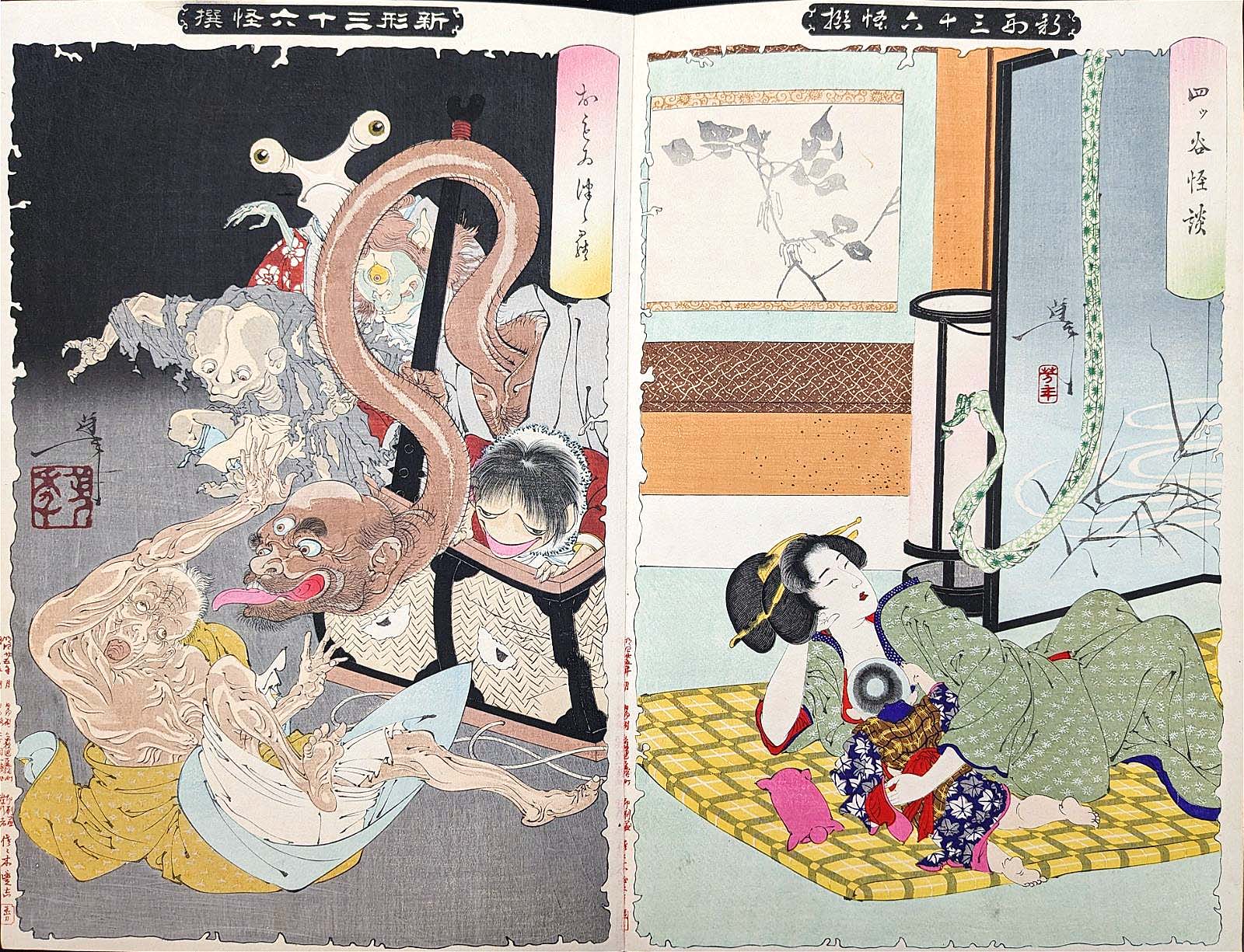

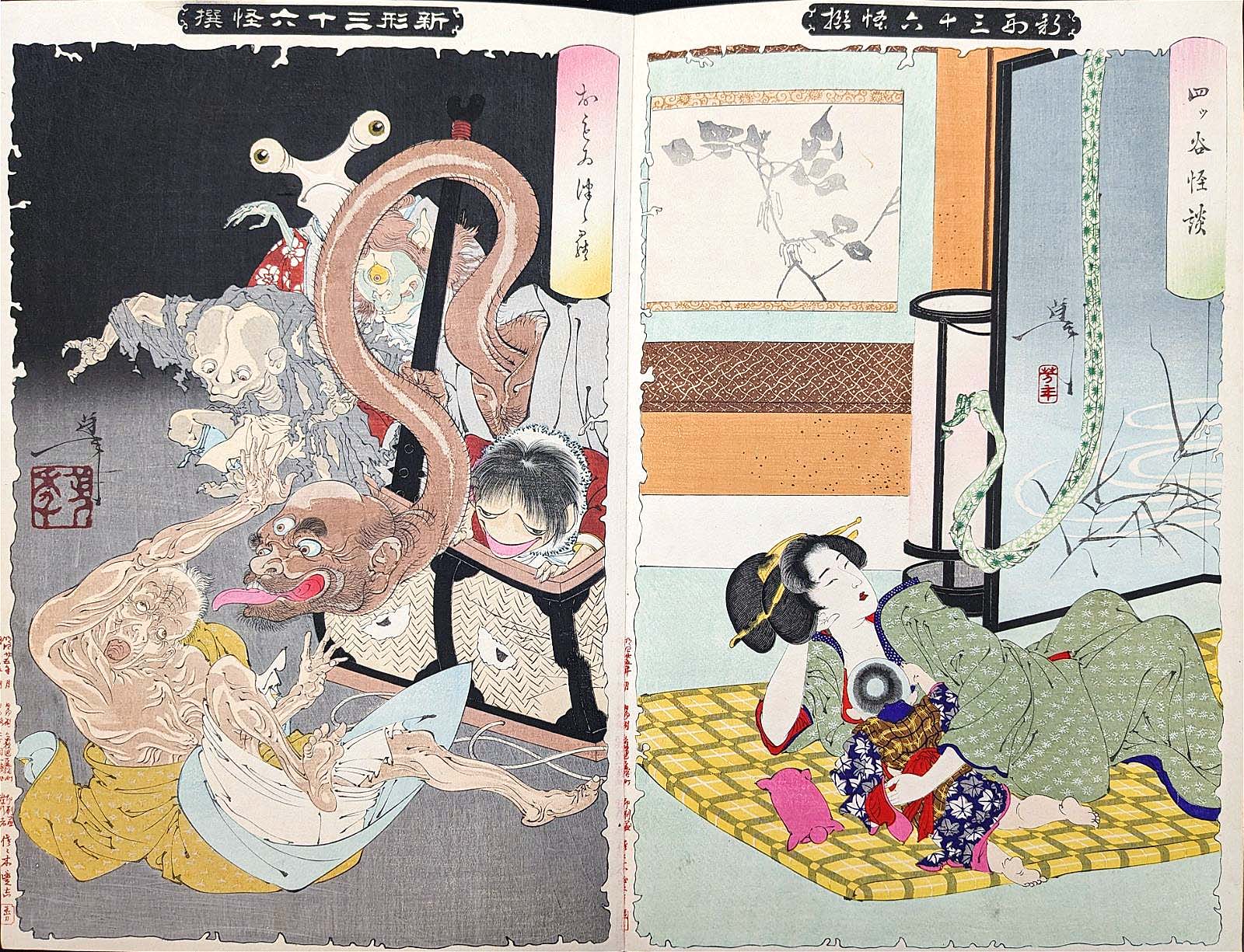

There were nine albums of Japanese woodblock prints. This one, “Thirty-Six Ghosts,” by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, brought the highest price, $19,840.

Three of the nine albums of Japanese woodblocks accounted for the second, third and fourth highest prices of the sale. Each had been done by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892), who is generally considered one of the last of the true ukiyo-e artists working in the mainstream of the late ukiyo-e tradition. His subjects included historical and heroic subjects as well as scenes of contemporary life and its increasing Westernization. His album, “Thirty-six Ghosts,” brought the highest price of the group, $19,840. It was complete with title/contents page, and the publisher’s Imperial commendation page and silk brocade covers. It was one of the artist’s last major works. An album of 32 woodblock prints, plus title/contents page, and publisher’s Imperial commendation page, titled “Thirty-two Aspects of Customs and Manners of Women” realized $16,120. “New Selection of Eastern Brocade Pictures,” an album with 19 diptychs, brought $9,300.

The majority of the collection comprised earlier prints. The first mezzotint published in America depicted Cotton Mather and was done in 1727 by Peter Pelham; it realized $5,208. Pelham is believed to only have produced about 15 different mezzotints and his portrait of Mather, a Colonial major religious leader, was done just a few months before Mather died. Bringing the same price, $5,208, was a series of 25 engravings done in 1642 by Francesco Bertelli that showed masked figures in costume for the masquerade at Venice’s carnival. Subjects included armored tourney fights, spectacles or games involving animals, landmarks in Venice and notable figures, to name a few.

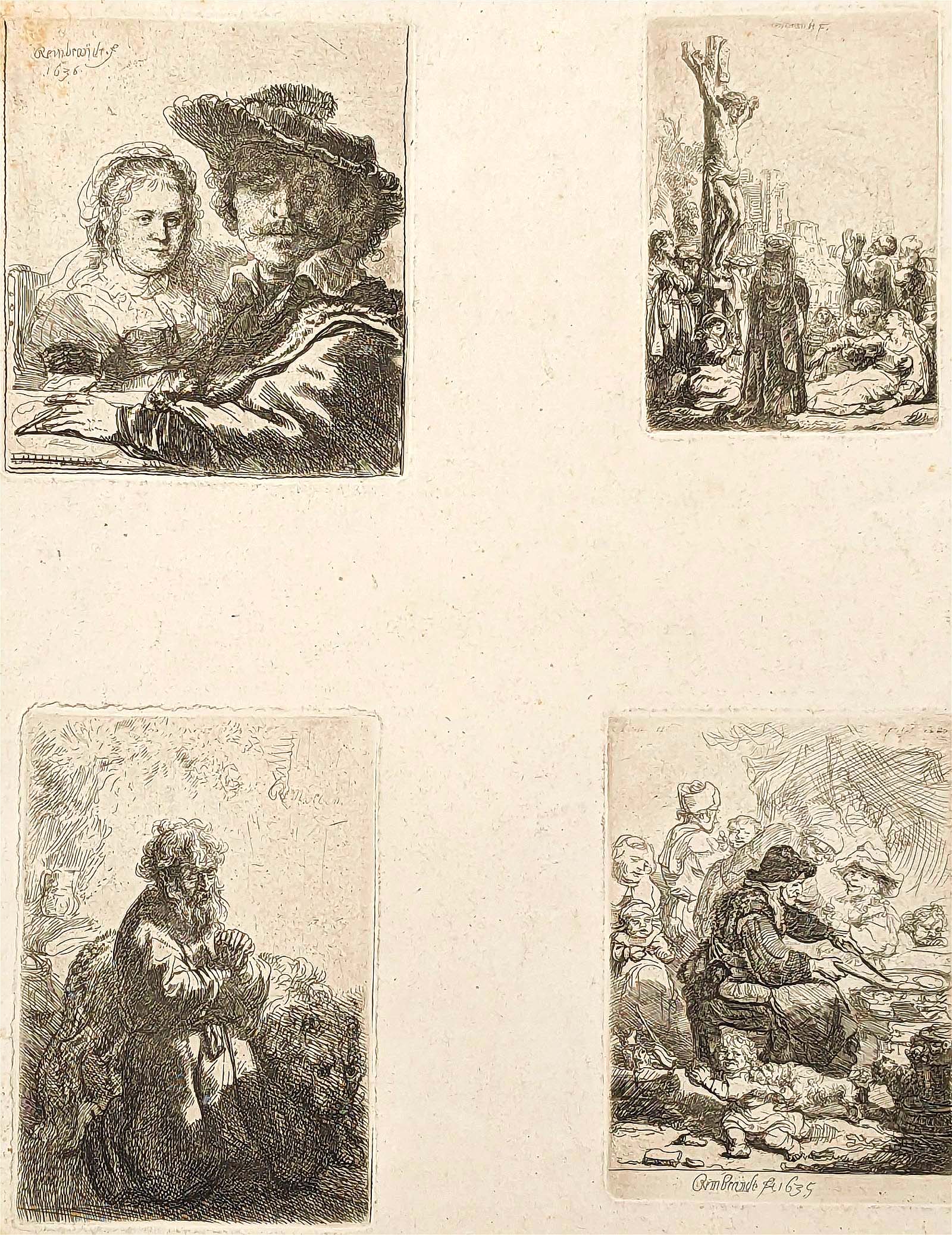

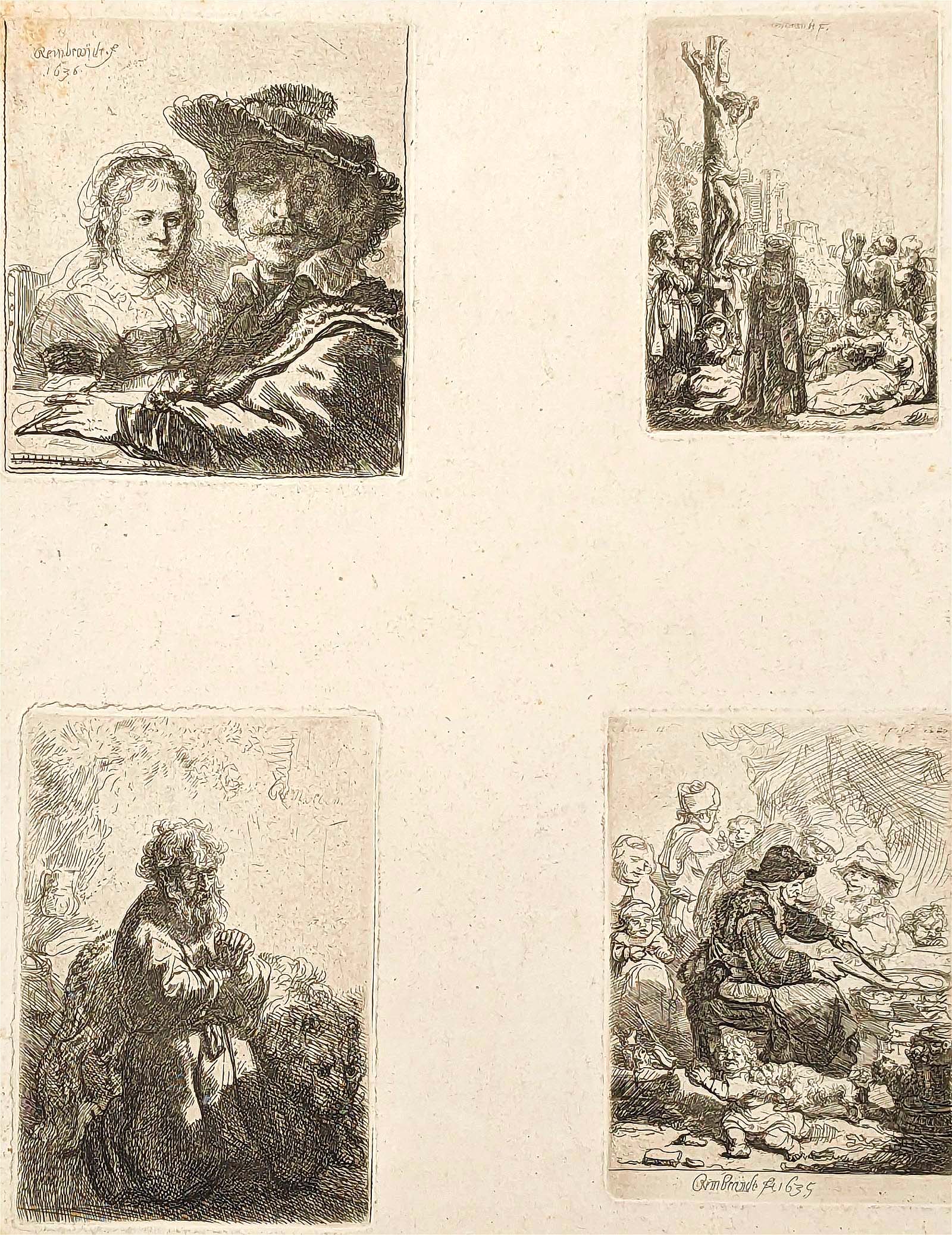

There were more than 50 prints by Rembrandt van Rijn. Four Seventeenth Century etchings, printed on one sheet of paper, brought the highest price of the group: $4,712.

Old Master prints included more than 50 engravings by Rembrandt, most of which sold to dealers. Four etchings on one sheet of paper which included a self-portrait, led the group, selling for $4,712. His 1635 “Christ Driving the Moneychangers from the Temple” sold for $3,720 and his 1654 “The Descent from the Cross by Torchlight” brought $3,472. Two of the 14 prints by Dürer each earned $3,720. One was a circa 1498 woodcut titled “The Holy Family with Three Hares” and the other was “The Martyrdom of St Catherine,” circa 1496-97. A 1666 Wenceslaus Hollar etching showing London before and after the fire of 1666 sold for $3,224. Appropriate notations from established reference sources were included in the catalog and there were multiple photographs of each lot.

After the sale, both owner Brett Downer and auction manager Cameron Ayotte were pleased with the results. Downer said, “We invested a lot of time and energy in this sale. It was a whole new field for us and it turned out well. Our guys went through every one of those prints to select the ones we thought would do well. Dealing with a municipal government was also a new experience and will enable us to do more of that in the future.” Ayotte also was pleased, noting, “We exceeded our expectations for the sale with most lots exceeding estimates. Only two lots weren’t sold, and I certainly learned a lot…both about history and the different early printing techniques.”

Prices quoted include the buyer’s premium as reported by the auction house. For additional information, 617-795-1678 or www.tremontauctions.com.

Tremont will sell an important Korean screen on March 15, estate art and antiques on March 25, a single-owner collection on May 5, rugs and carpets on June 16 and Asian art and antiques on July 14.