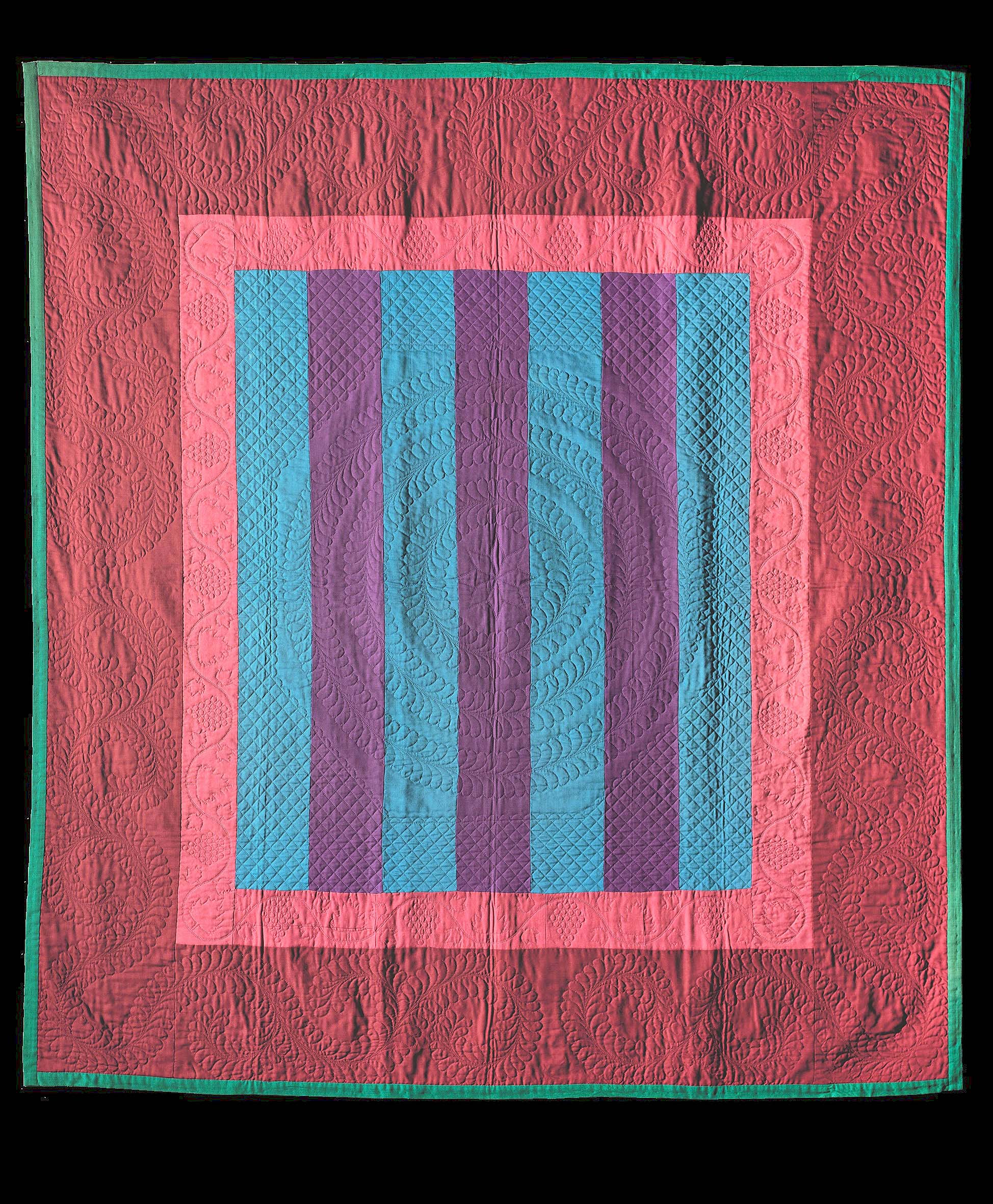

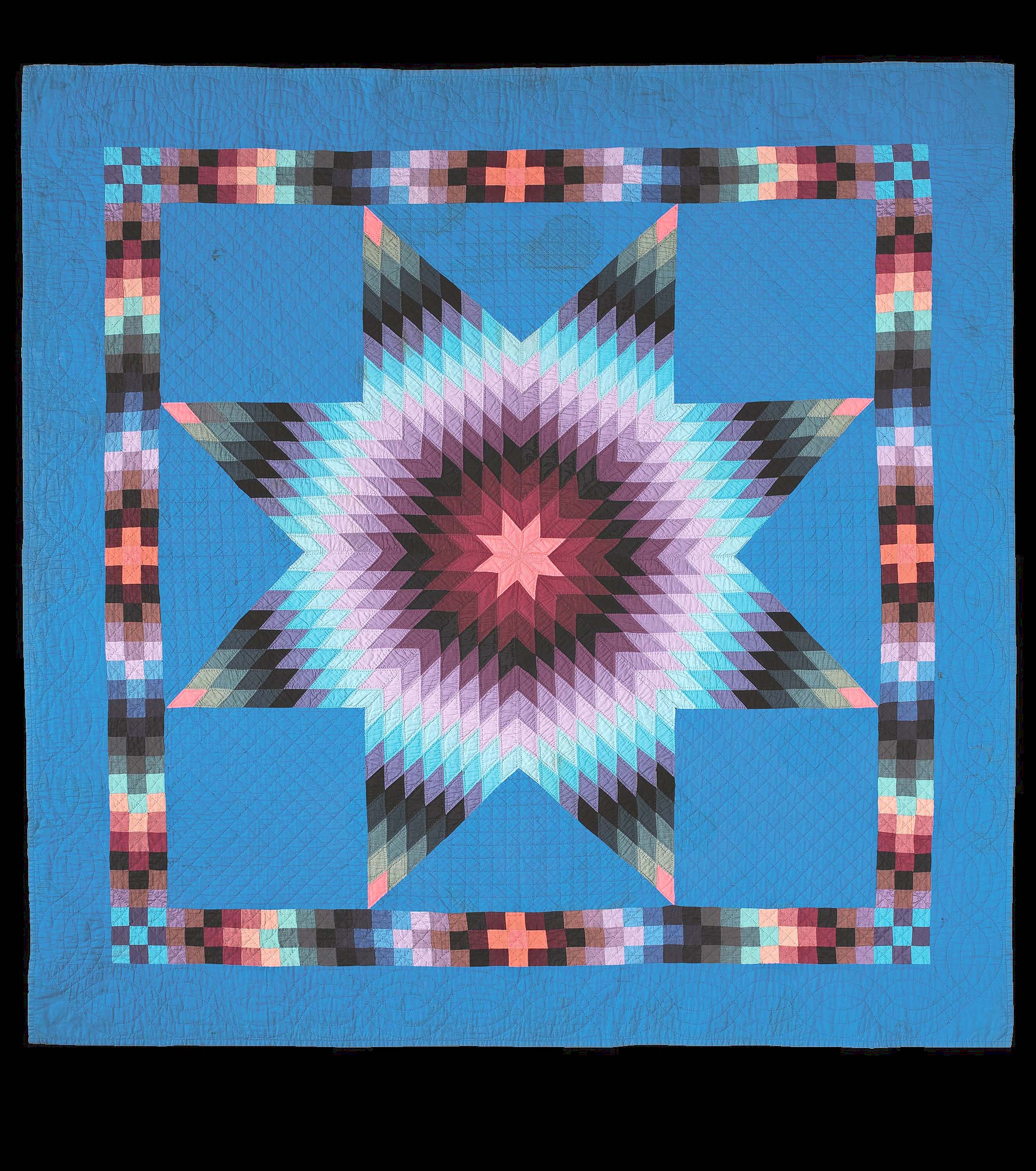

“Lone Star” by an unidentified maker, Smoketown, Lancaster County, Penn., circa 1935-45, cotton and wool, 81 by 82 inches. From the Lapp family, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Faith and Stephen Brown, 2022.4.10. The graduated arrangement of colors gives this quilt a pulsating effect that is further distinguished by a border made from fabrics not used elsewhere in the design.

By Madelia Hickman Ring

WASHINGTON, DC — “Plain” is a term frequently used to describe the Amish, referring both to their simple style of living as well as to their dress: their clothing leans towards a conservative style in comparatively dark solid colors that shuns fancy or flashy ornament or trim. The term, however, belies the vivid colors and patterns — some spectacularly complex — that characterizes the silk, woolen or cotton quilts made by Amish women from the mid- to late Nineteenth Century and through the Twentieth Century.

It is this exact paradox — that such complex and colorful textiles were made by people largely known for their simplicity — that is at the heart of the recently opened exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM). “Pattern and Paradox: The Quilts of Amish Women,” which will be on view through August 26, presents 50 quilts in an exhibition that not only examines the Amish practice of quilting from the last quarter of the Nineteenth Century through the first half of the Twentieth Century but also explores contradictions inherent in celebrating as works of art objects inherently made as functional domestic goods.

All the quilts in the exhibition are from the collection of Faith and Stephen Brown. Five were donated to the museum in 2021, with another 34 given the following year; the remaining quilts on view — 11 in total — are promised gifts. Ultimately, the Browns plan to bequeath about 100 quilts.

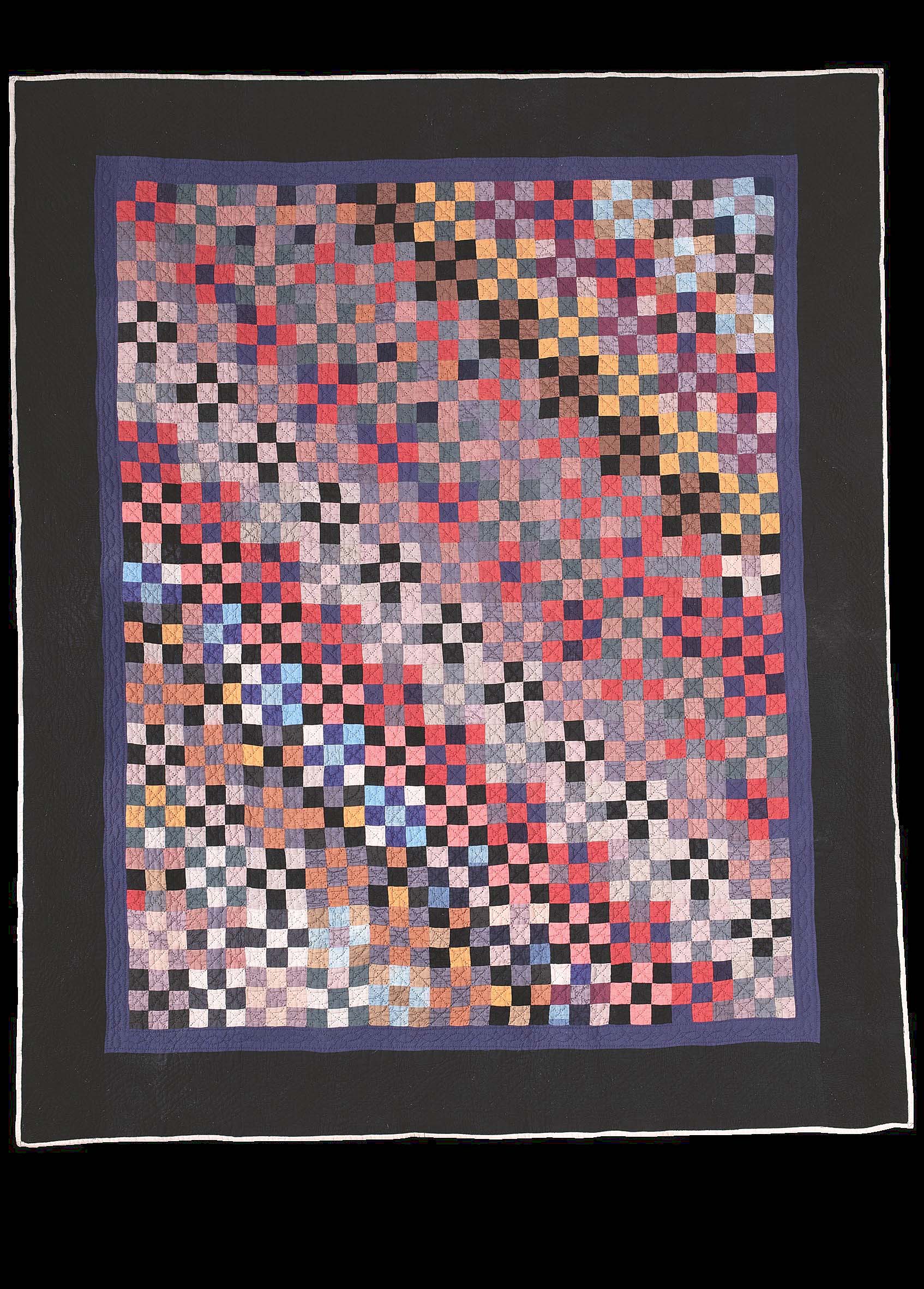

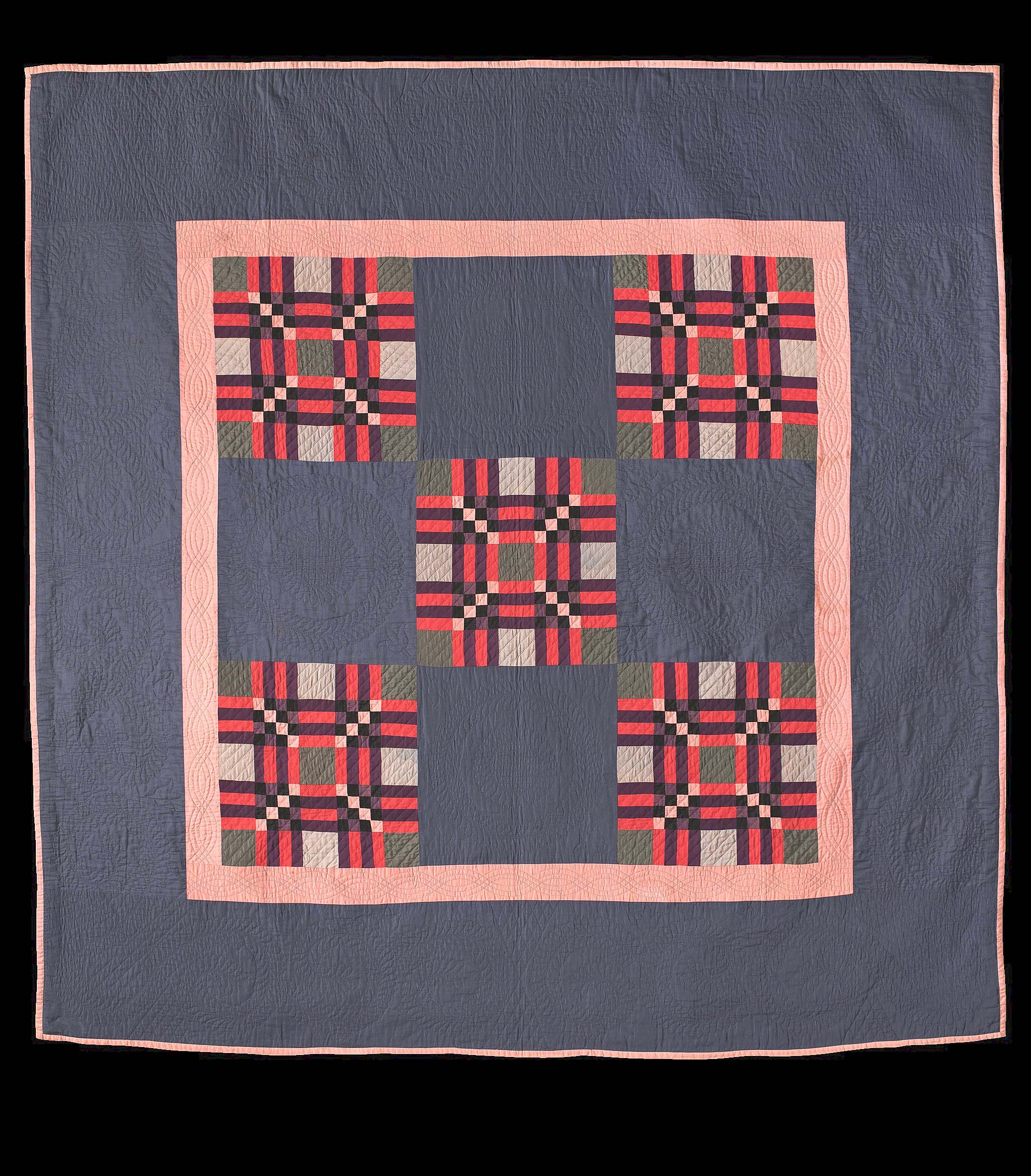

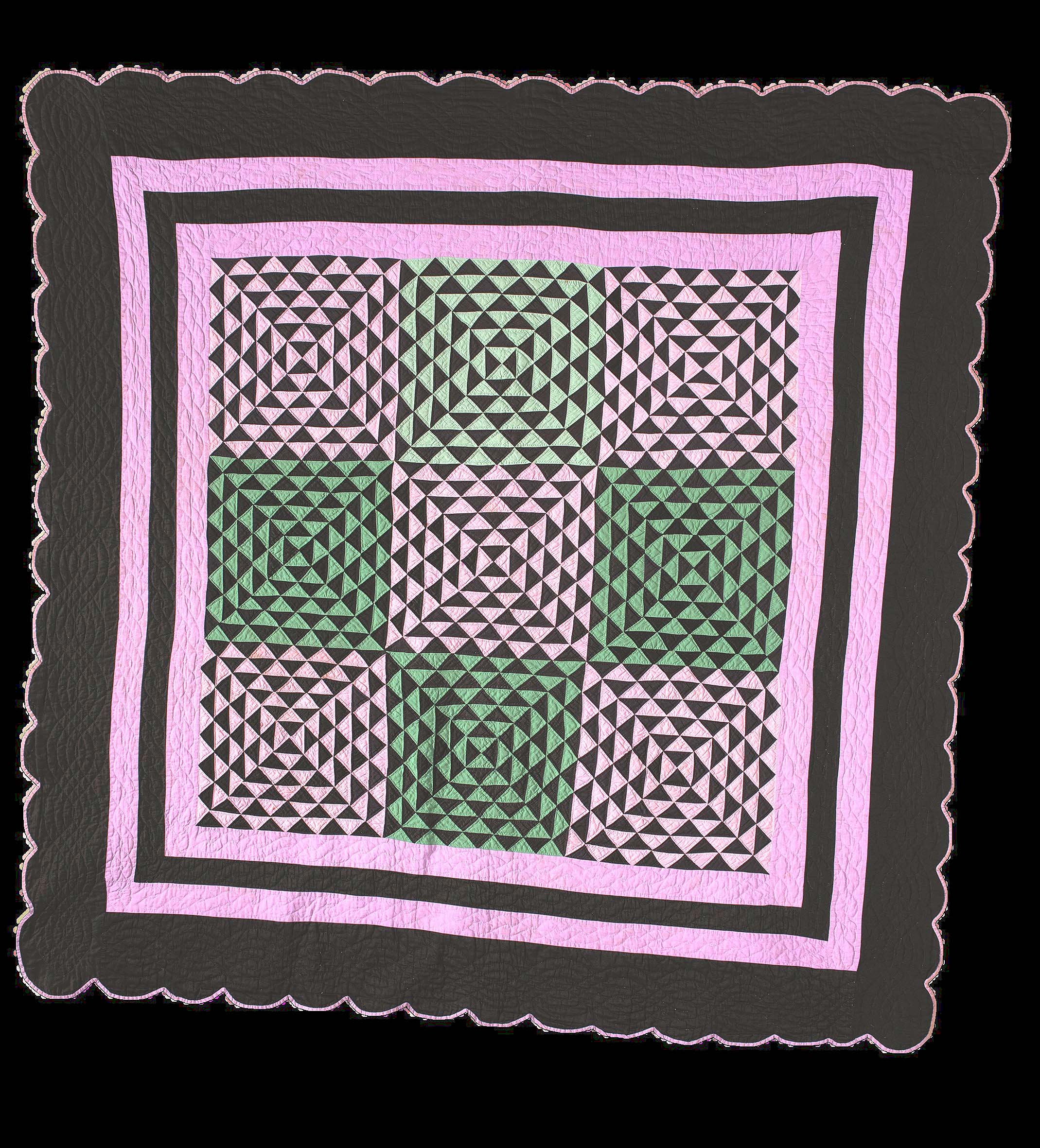

“Nine Patch, Puss in the Corner” variation by an unidentified maker, possibly Mifflin County, Penn., circa 1930, cotton and wool, 79½ by 70 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Faith and Stephen Brown, 2022.4.33. A repeated stretched “Nine Patch” variation, such as this one, relates to examples made in Amish settlements in the Kishacoquillas Valley of central Pennsylvania.

Leslie Umberger, the museum’s curator of folk and self-taught art and co-curator of the exhibition alongside Virginia Mecklenburg, senior curator of painting and sculpture at the museum, shared the genesis for the show with Antiques and The Arts Weekly. “When I began at SAAM in 2012, I identified the quilts of Amish women as an area that was very underrepresented in the collection. I began looking for examples we might acquire, but Amish quilts from the historic late Nineteenth to mid-Twentieth Century period are increasingly rare in the marketplace. Most are held in either private or institutional collections, so I knew it would take some time. On their end, Faith and Stephen Brown were looking for a forever home for the exceptional collection they had built over some four decades. Both parties recognized the ways in which our goals dovetailed. It took some time to tailor the specific plan — but all parties agreed that an exhibition and book would be organized to celebrate the gift and convey the importance of representing Amish women within the broader field of American art.”

She further characterized their gift as “the largest and most widely representative group of Amish quilts ever acquired by a major art museum.”

The Browns were first introduced to Amish quilts in 1973, at the Renwick Gallery’s show, “American Pieced Quilts,” which opened two years after the Whitney Museum of American Art’s seminal show, “Abstract Design in American Quilts.” In a “Collector’s Note” at the front of the Pattern and Paradox catalog, they write, “We never planned to collect Amish quilts. What little we knew about the Amish centered on their austere, seemingly old-fashioned lifestyle. We could not have imagined an intersection between the so-called “plain people” and our own interests,” going on to describe being attracted to “the creativity of the designs, the multiple variations on geometric patterns, the unusual color combinations and the optical illusions.”

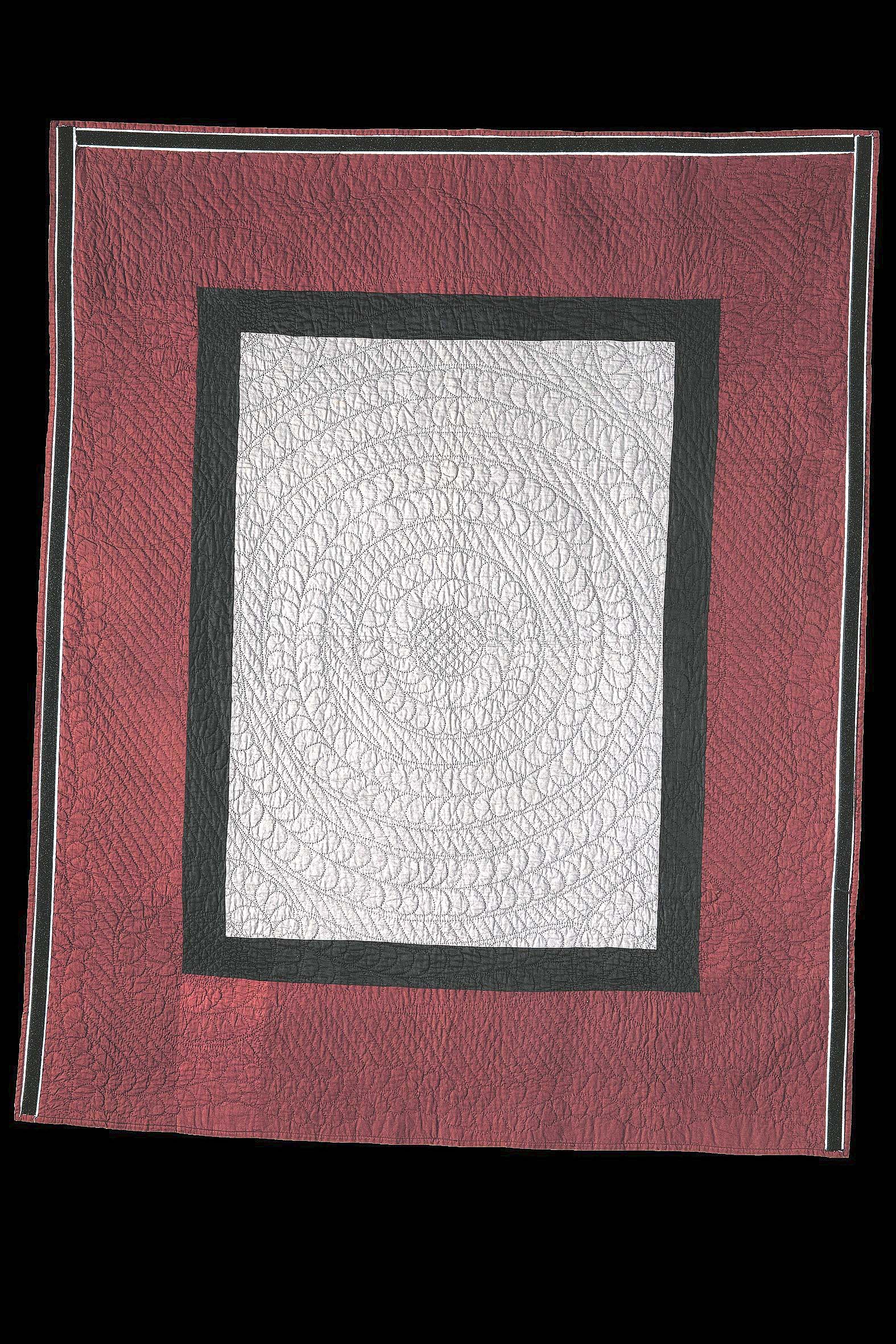

“Double Wedding Ring” by an unidentified maker, Holmes County, Ohio, circa 1940-50, cotton, 75 by 66 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Faith and Stephen Brown, 2022.4.28. The “Double Wedding Ring” pattern was first published commercially in 1928 and — due to its associates with love and marriage — has long been a popular one with quiltmakers, both Amish and non-Amish. This one’s dark ground and broad outer border are characteristically Amish and the pieced border is considered particularly appealing.

When asked what the strengths and unique aspects of the exhibition, Umberger noted that researching and writing about the quilts in the collection had been a collaboration between herself, Mecklenberg and Janneken Smucker — professor and historian specializing in digital history, public history and material culture at West Chester University — who has authored Amish Quilts: Crafting an American Icon (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013) and A New Deal for Quilts (International Quilt Museum, 2023). Smucker authored the catalog that accompanies the exhibition.

Herself a quilter and descendant from her Amish-Mennonite great-grandmother and Mennonite grandmother, Smucker lends what Umberger credits as “invaluable depth and sensitivity to the cultural and religious contexts of these quilts. Her expertise extends also to quilts in general: fabrics, methods, historical trends and many other details that helped us read these quilts through their material and aesthetic clues.”

Despite her experience making and working with Amish quilts and having some familiarity with some of the Browns’ quilts through previous exhibitions and published examples, Smucker still found some revelations in their gift.

“This collection has both breadth and depth, with examples that will totally knock your socks off, as well as multiple variations of the same patterns that allow you to see the ways communities as well as individual quiltmakers have made adapted patterns, making quilts that reflect both tradition and individuality.”

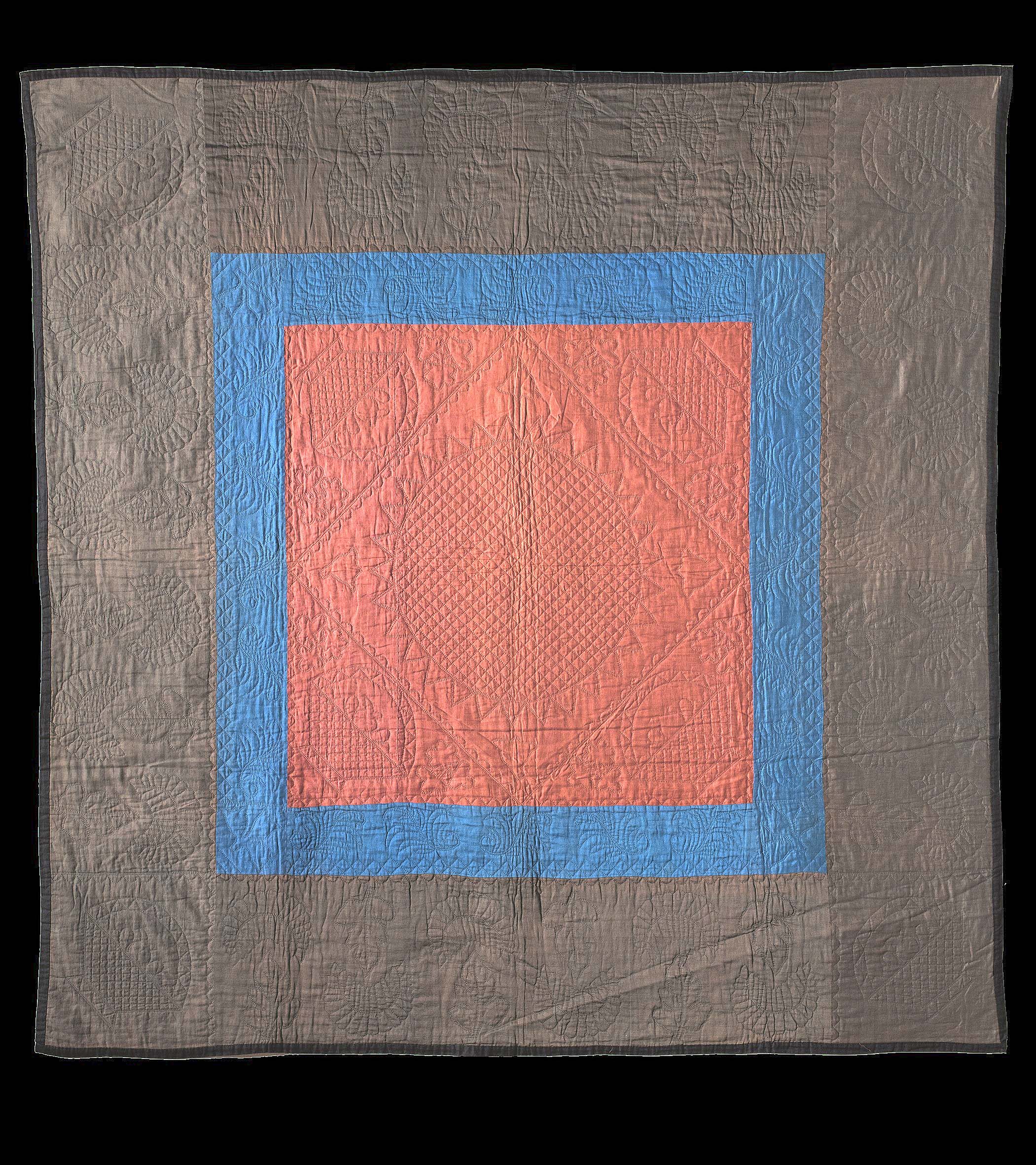

“Fans” by an unidentified maker, probably Indiana, circa 1915, cotton and wool, 77 by 71½ inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Faith and Stephen Brown, 2022.4.12. Non-Amish quiltmakers in the late Nineteenth Century were attracted to the “Fans” pattern, but this example features the characteristic Amish wide outer border: solid colored fabrics neatly outlined with embroidery stitches.

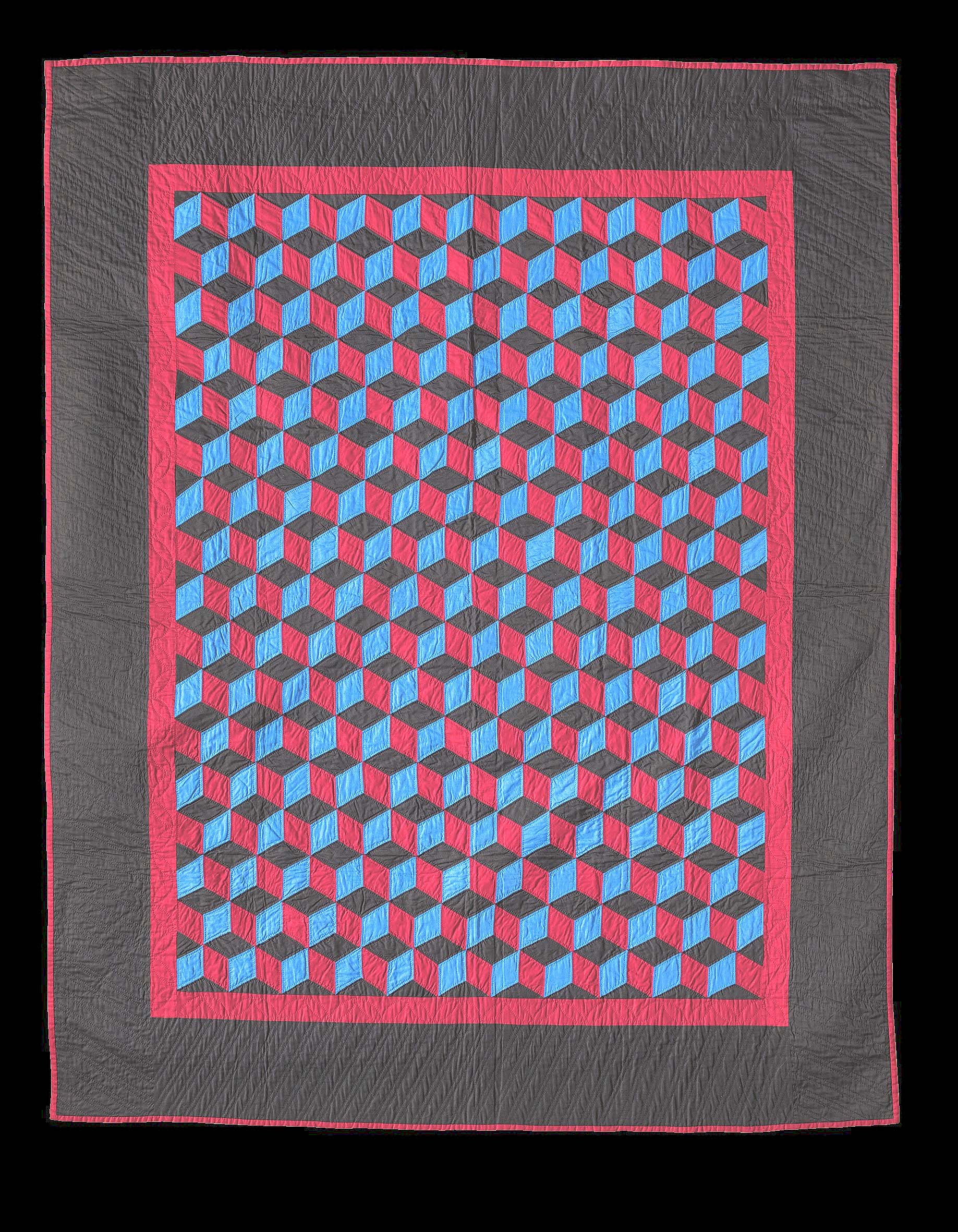

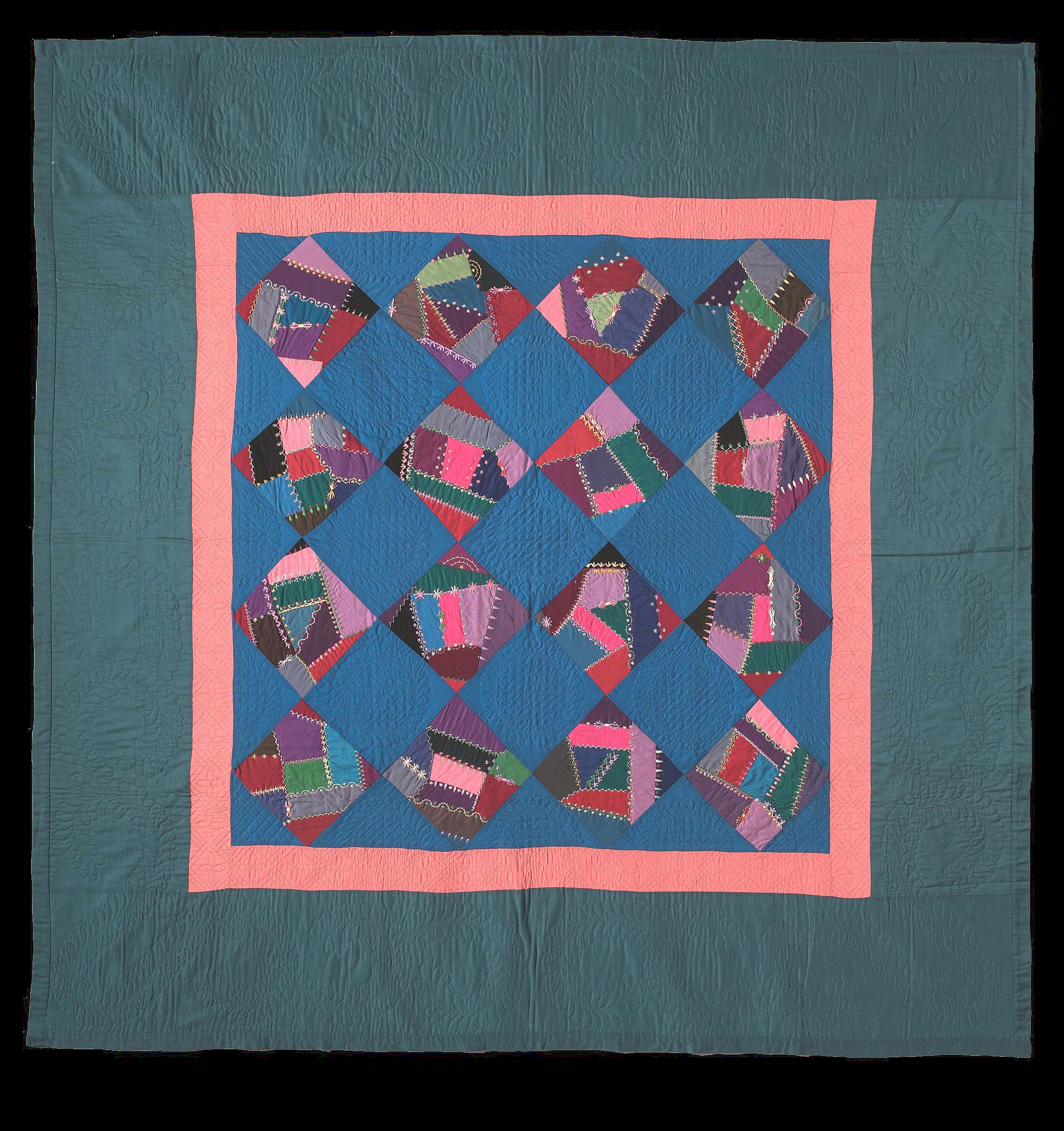

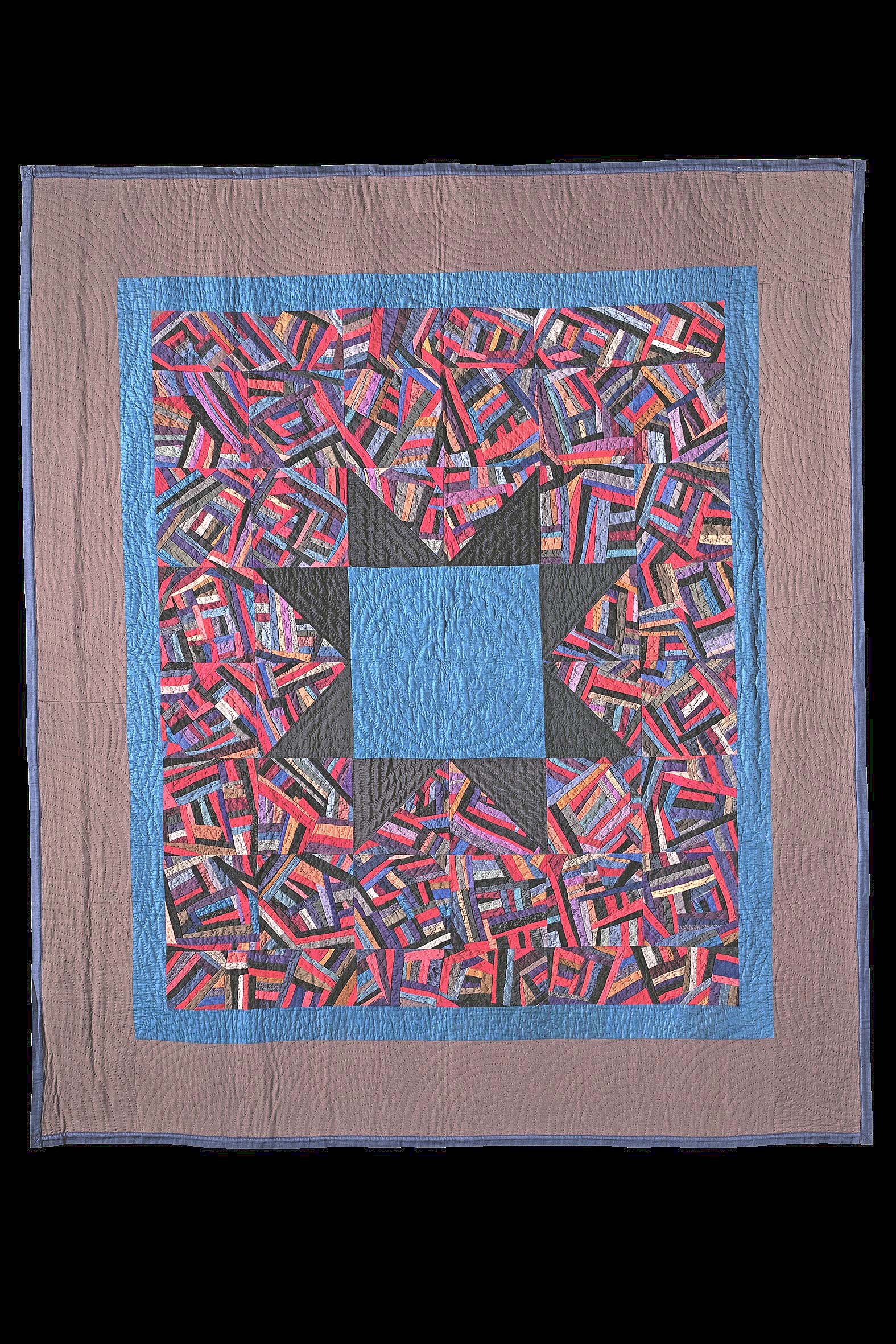

The jewel-like catalog is thus divided, arranged by pattern names that follows contextualizing essays on Amish quilts. Comparatively simple patterns that are called “Center Diamond,” “Bars” and “Center Square” give way to more complex configurations, the very names of which lend a unique romanticism: “Sunshine and Shadow,” “Tumbling Blocks” “Fans” and “Crosses and Losses.” One wonders how those patterns so complicated — largely featured towards the end of the catalog — acquired such names as “Broken Star,” “Crazy Star,” “Railroad Crossing,” “Broken Dishes” and “Ocean Waves.”

Amish women did not seek to take credit for making quilts and they rarely signed them; this posed a challenge for the curators. In her examination of the Brown’s collection, Smucker outlines a few salient factors — pattern, fabric, color, the history of a quilt and the occasional set of stitched initials or date — that can provide a clue to the “where” and “when” the quilt was made, if not by precisely “who” made them.

Another paradox the exhibition highlights is the contradiction that these quilts were made originally as utilitarian objects by women who neither viewed them as art nor meant for them to be seen in an exhibition setting. Umberger hopes that viewers to this exhibition that celebrates both the quilts “dual identity: part icon of Amish culture, part abstract artwork…ponder the essential gap between intention and inception while also pausing to value both Amish and non-Amish perspectives on the artworks.”

The Smithsonian American Art Museum is at Eighth and G Streets, Northwest. For information, www.americanart.si.edu or 202-633-1000.