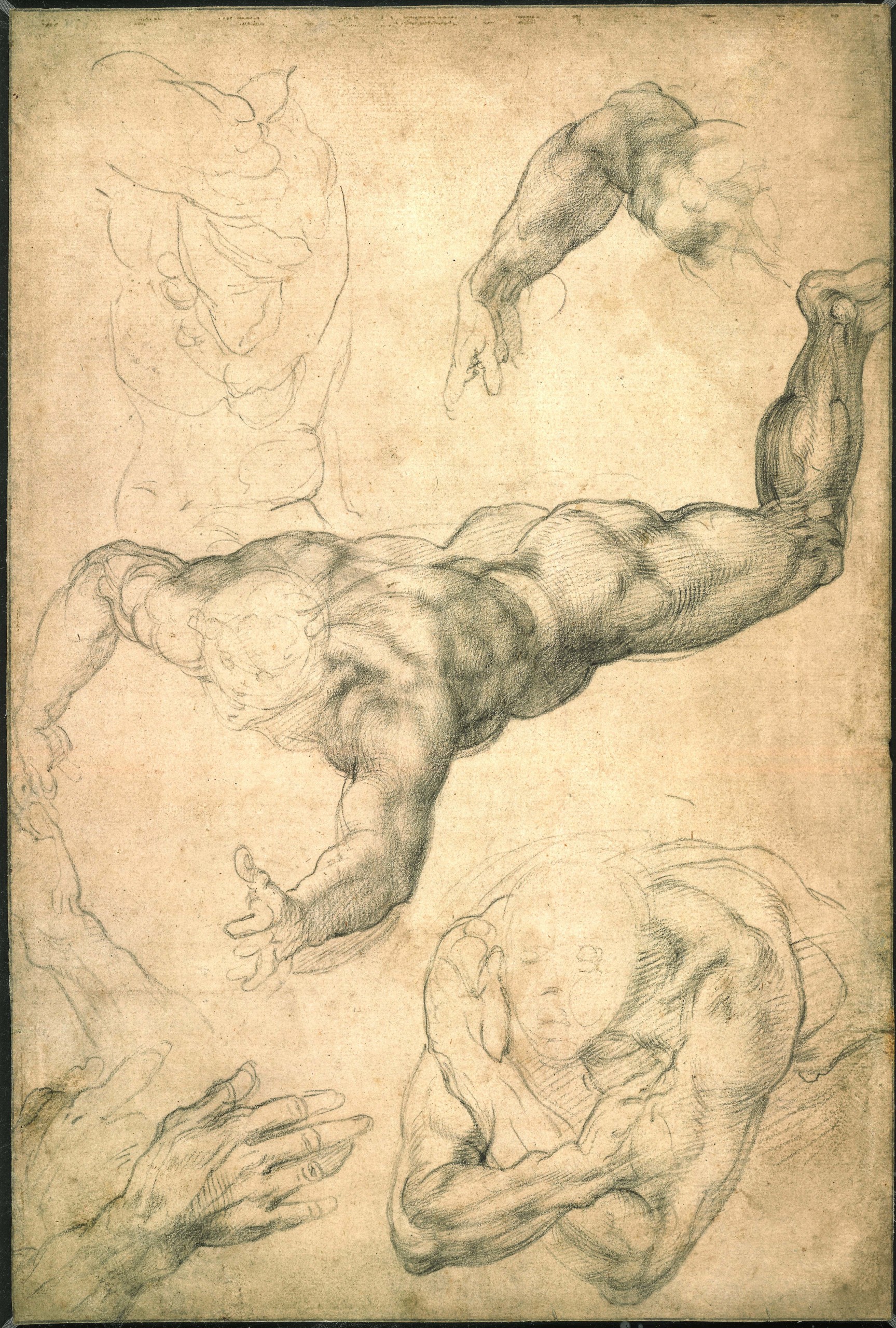

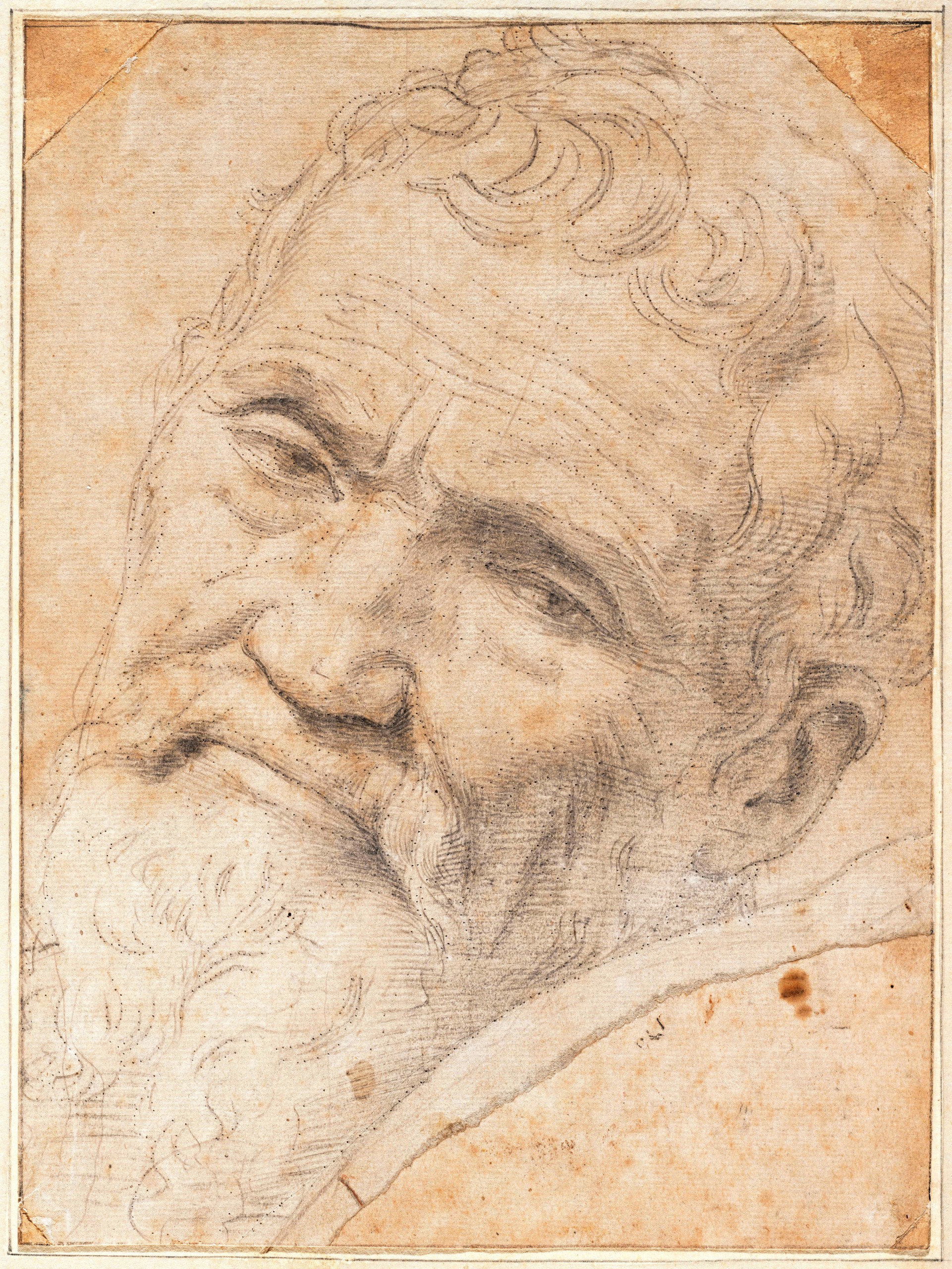

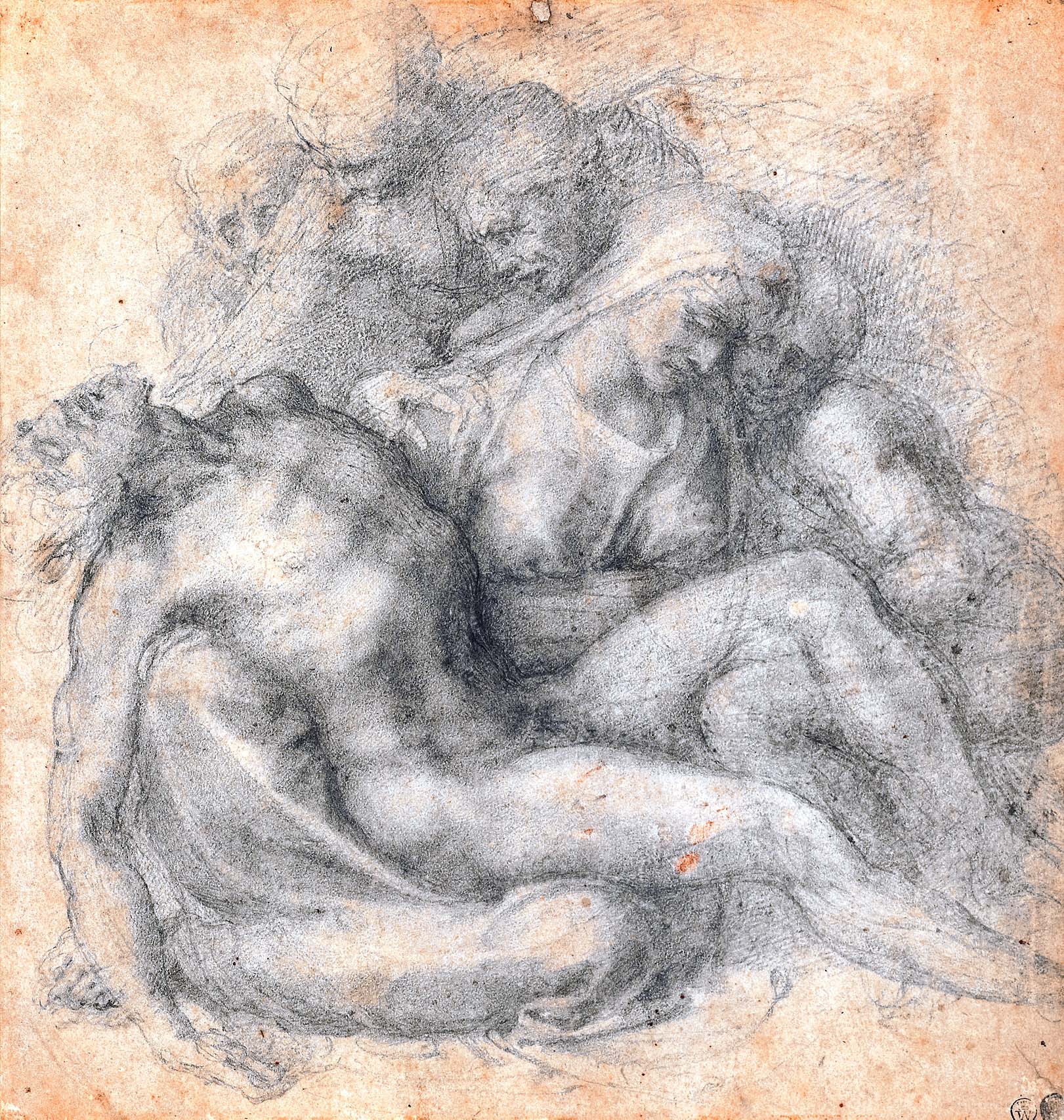

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), study for “The Purification of the Temple,” circa 1550, black chalk on paper. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

By James D. Balestrieri

LONDON — You crowd around Michelangelo’s “David.” Like the rest of them, you came to the Accademia in Florence to see Michelangelo’s “David.” Which is everything you imagined. Taller. Larger. Impossibly slender. You walk around it and the torsion of the body is endlessly elusive. Then, when you’re done — and only the next wave of the crowd moves you on — you notice, down a hallway, four imposing sculptures, figures that seem as if they are trying to writhe and twist their way out of the stone, as if the marble is giving birth to them or that the marble is trying to absorb and reassimilate them. These are Michelangelo’s “Slaves.” You expected to feel awe before the “David,” and you did. But this — these — the “Slaves,” are something else again. They are, as Italian Renaissance scholars say, non finito, which means “unfinished,” but with more than a hint that “unfinished” is deliberate. There is something so — to use a hackneyed word — modern about them, about their roughs and smoooths, about the finished flesh and the uncarved marble, about Michelangelo’s mark making, not with brush or pen, but with a chisel. You read that these were intended for the Tomb of Pope Julius II in Rome, a project that vexed Michelangelo, a project whose design changed a dozen times and remained unfinished for decades. You read that Michelangelo might have left them unfinished on purpose. For some reason, for decades afterwards, up to the very moment of this assignment, to write about “Michelangelo: The Last Decades,” an astonishing new exhibition at the British Museum, you — meaning me — believed that these were quarry slaves, men yoked to the rock, men who were products of the rock.

Despite finding no evidence, I defend my interpretation. The “Slaves” remain and retain some air of mystery. They seem to have been carved during the period when Michelangelo was making what would be his final move, from his native Florence to Rome, but the actual dates vary from scholar to scholar.

Whatever the case, the “Slaves” are caught between two states of being.

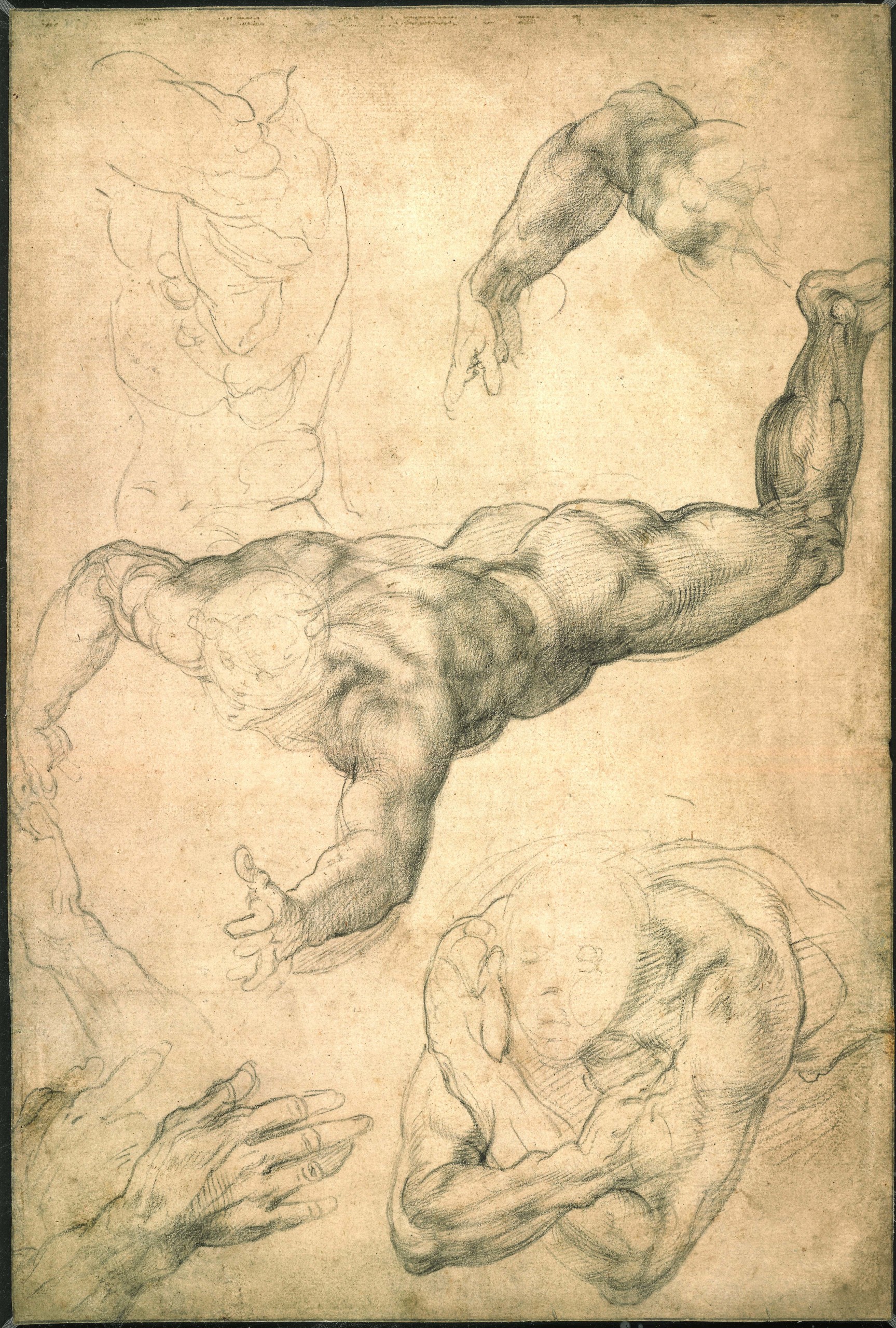

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), “Angels (Last Judgement study)” circa 1534-36, black chalk on paper. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

Having read the fine accompanying catalog, pored over the images of the objects, and adventured down some scholarly rabbit holes on my own, “between two states of being” might well serve as the subtext of the exhibition.

By the late 1520s, Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) was in a bind. In his 50s, he was already famous for any number of masterworks, from the Sistine Chapel ceiling to the “David.” But Florentines had had just about enough of life under Medici rule (via Pope Clement VII) and they rose up to restore the Florentine Republic. Republican forces even damaged the “David,” a Medici commission. Though since Michelangelo had helped design the republican fortifications and since, after all, he was Michelangelo, one gets the feeling that the minimal damage to the statue was more symbolic than anything else. Yet Michelangelo found himself caught between the republic he supported and the Medici he served. When the short-lived republic fell in 1530, the great artist must have seen the writing on the wall — Florentine turmoil was about to turn yet another of her luminaries into an exile (compare with Leonardo da Vinci and Dante Alighieri). He managed to keep working on the church of San Lorenzo for the Pope, and also to keep his head down, but when Pope Clement summoned him to Rome in 1534 to paint “The Last Judgement” on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel, he made haste to comply despite the fact that he had loathed the body-breaking process of painting the ceiling in the Chapel.

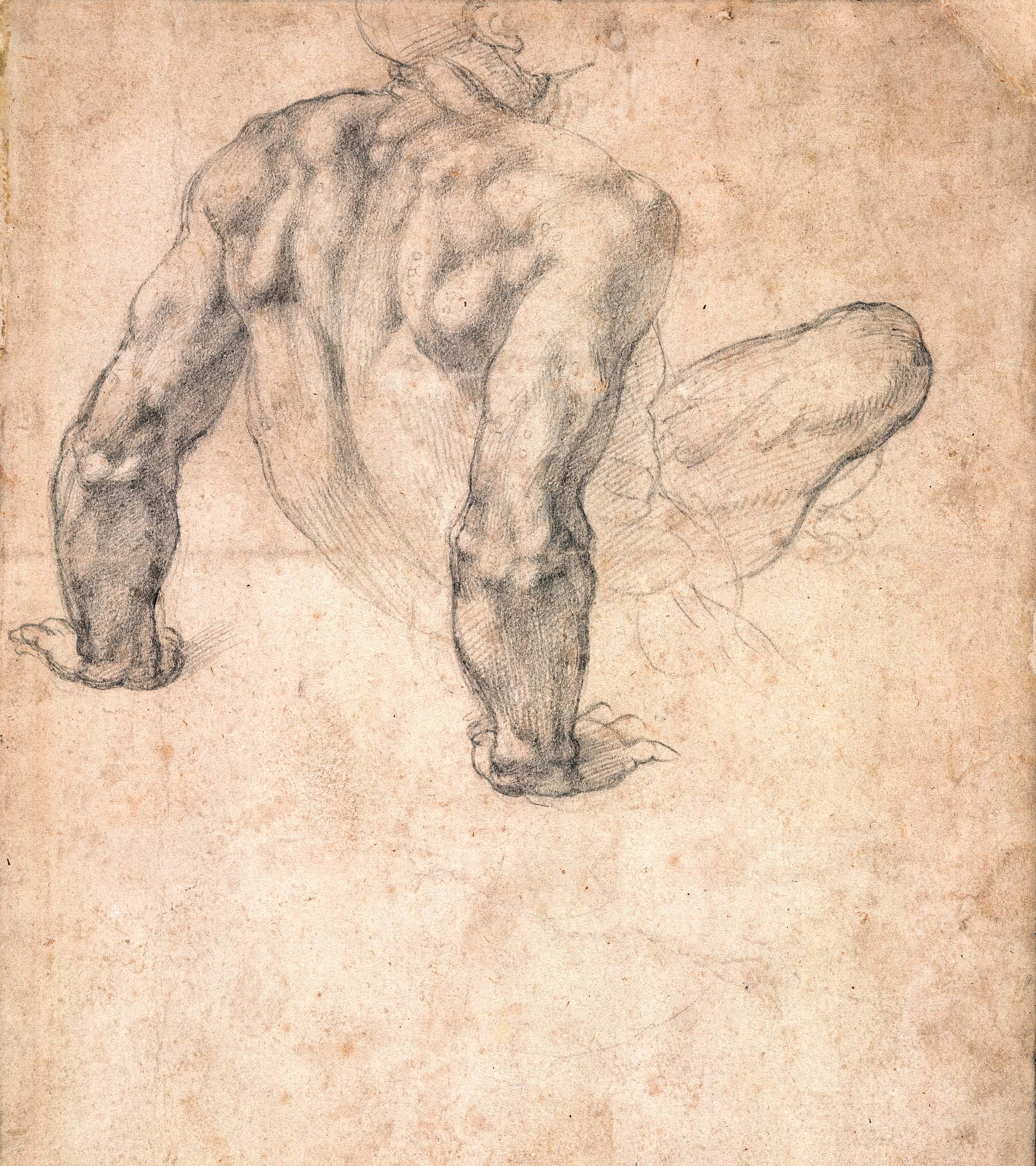

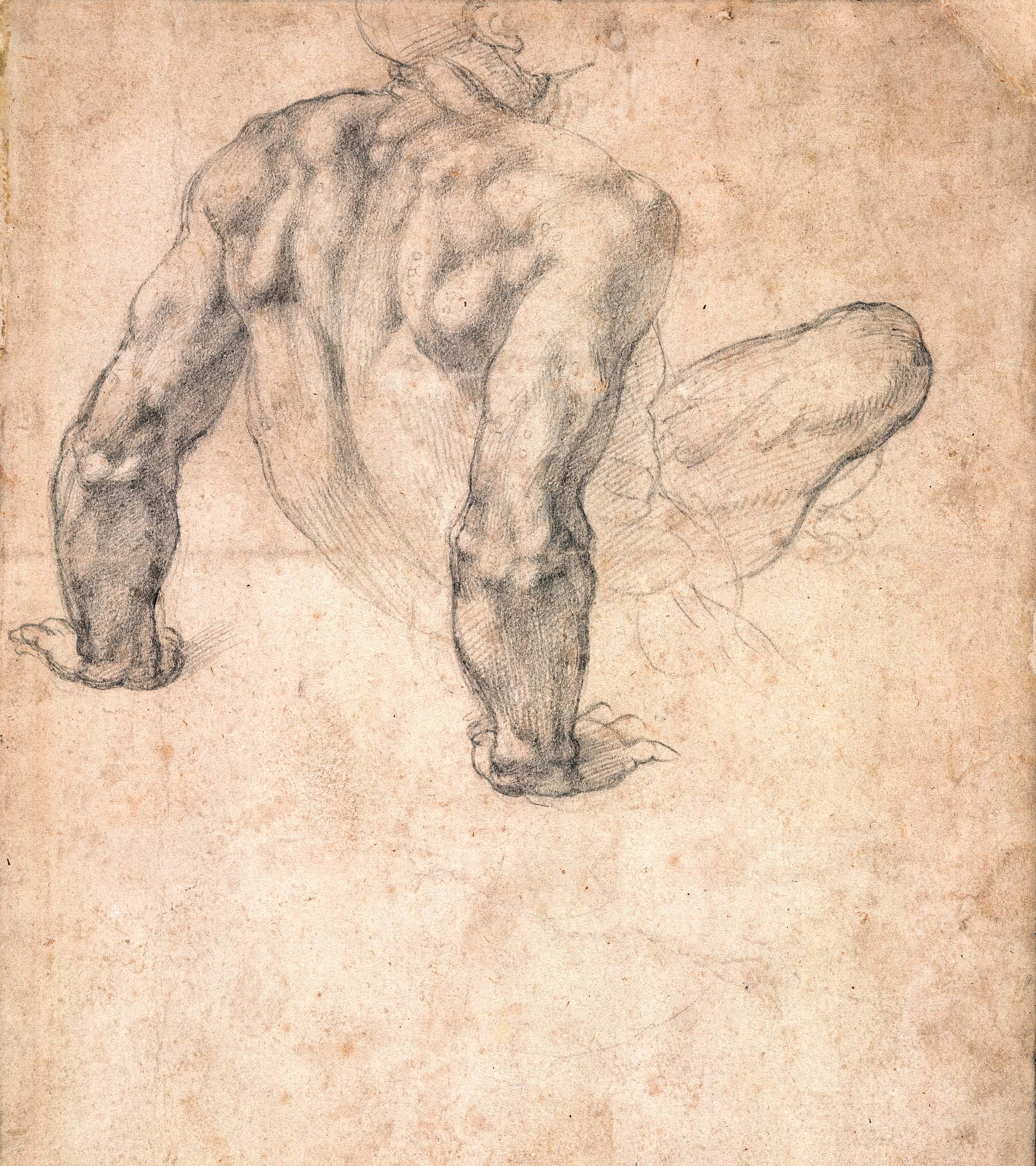

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), study for “The Last Judgment,” circa 1534-36, black chalk on paper. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

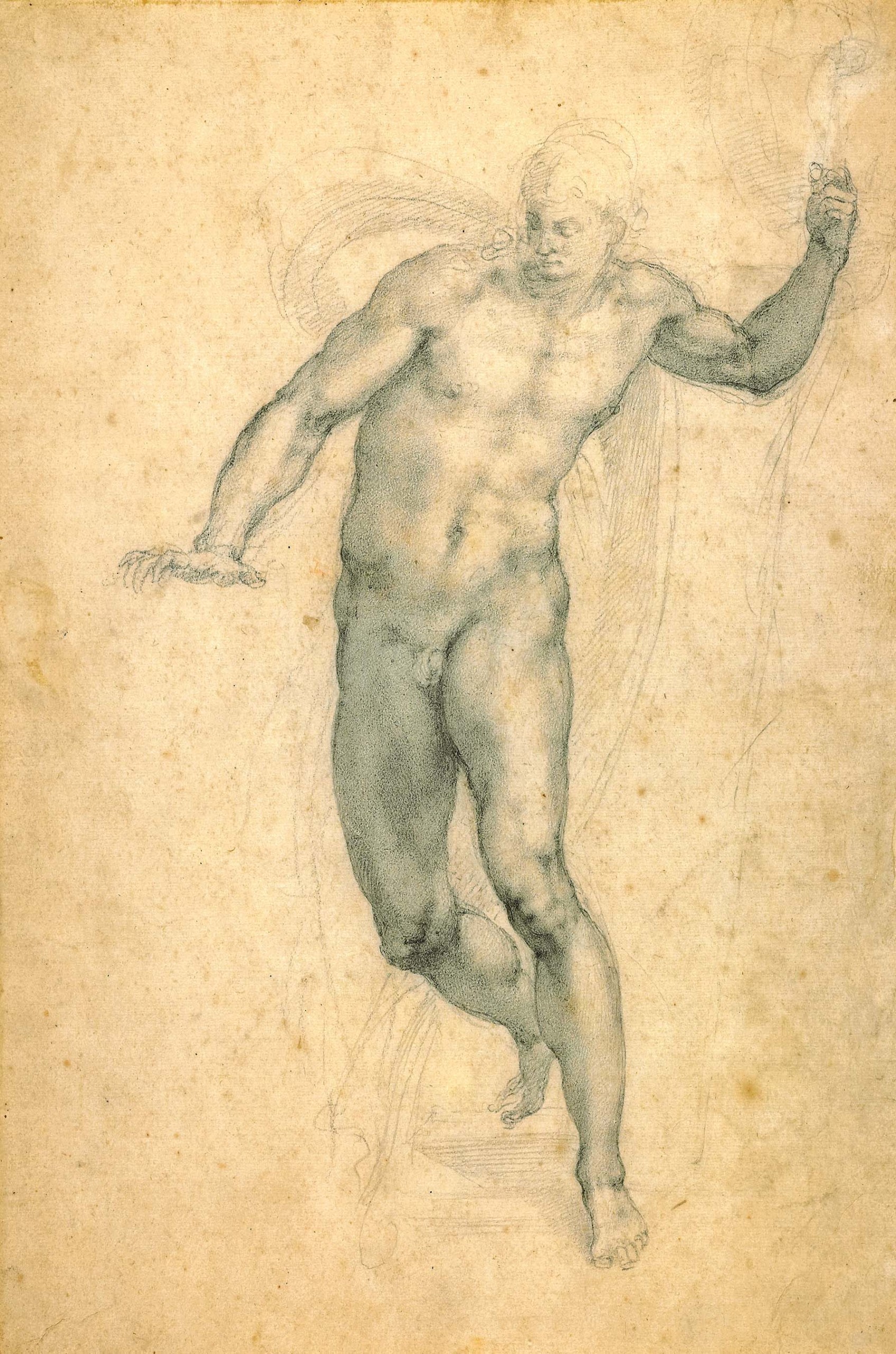

He would never see Florence again. He was 59 years old and beginning to think about — and even plan for — the end of his life. Yet, he would live until very near to his 89th birthday, working steadily through three extremely productive and creative decades in which he would be caught between his ever-youthful ambition and the ever-advancing realities of his aging body. He would lament many of the commissions he took and then he would throw himself into them. He would restlessly draw, paint, sculpt, design and write poetry. He would keep up a lively correspondence and would regularly participate in a salon-like social life of sorts, conversing and sparring with the humanist lights of the day. All of this would find him caught up in the tumultuous political and cultural climate of the mid-Sixteenth Century.

Rome had been sacked by Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in 1527. Raphael, who had been chosen to direct the excavation of ancient Rome and the rebuilding of the city, had died unexpectedly in 1520. Pope Clement and his successors, Paul III and Paul IV, saw a need to restore Rome as the glorious hub and heart of Christianity, and Michelangelo was a key to their endeavor.

Above all, Michelangelo drew. What’s more, he drew friends, not as commissions, but because he wanted to. More even than that, he gave drawings away. Word of his drawing spread like wildfire. He received requests and showers of gifts that givers hoped would be repaid with drawings.

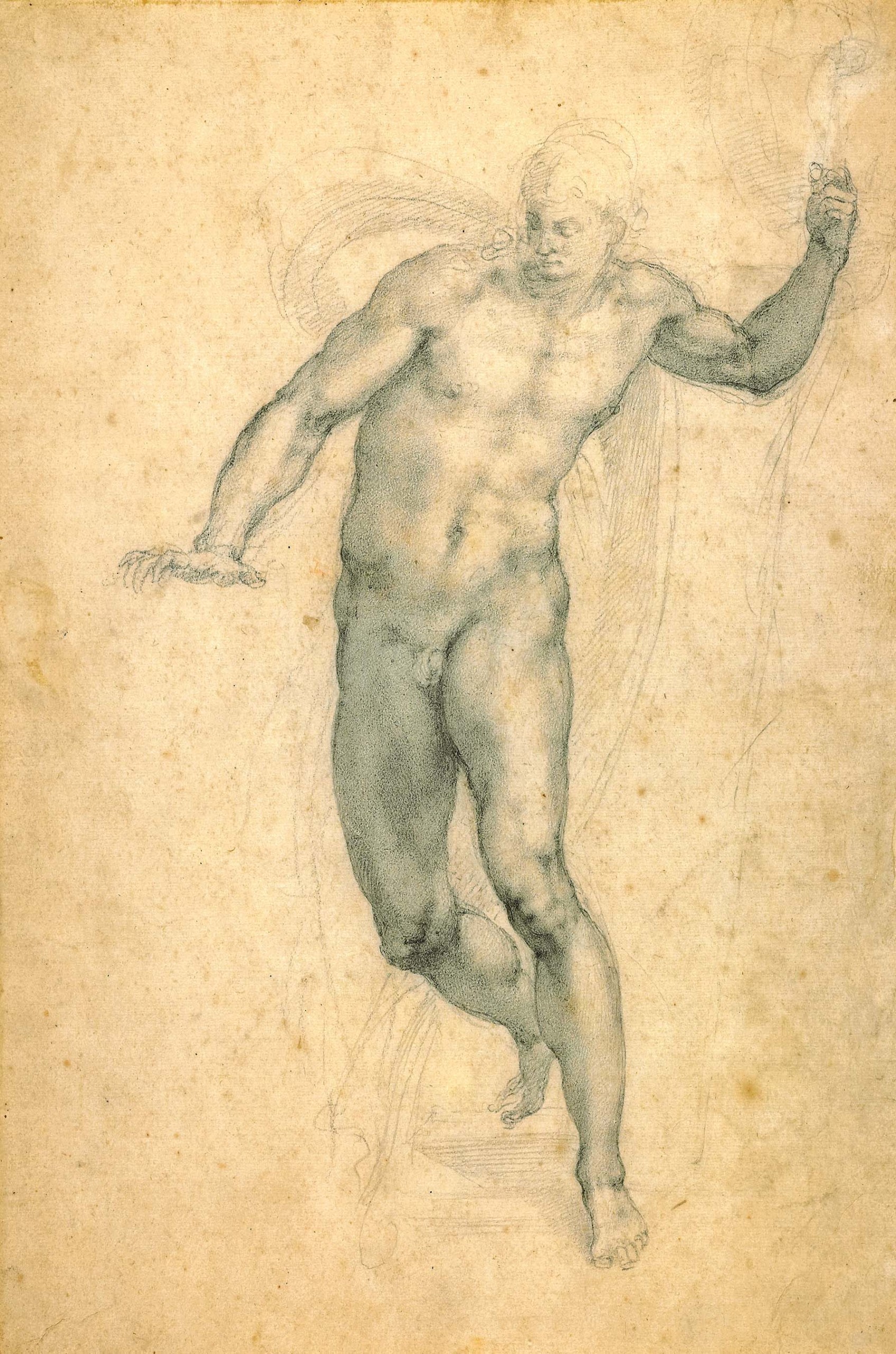

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), “The Risen Christ,” circa 1532-33, black chalk on paper. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

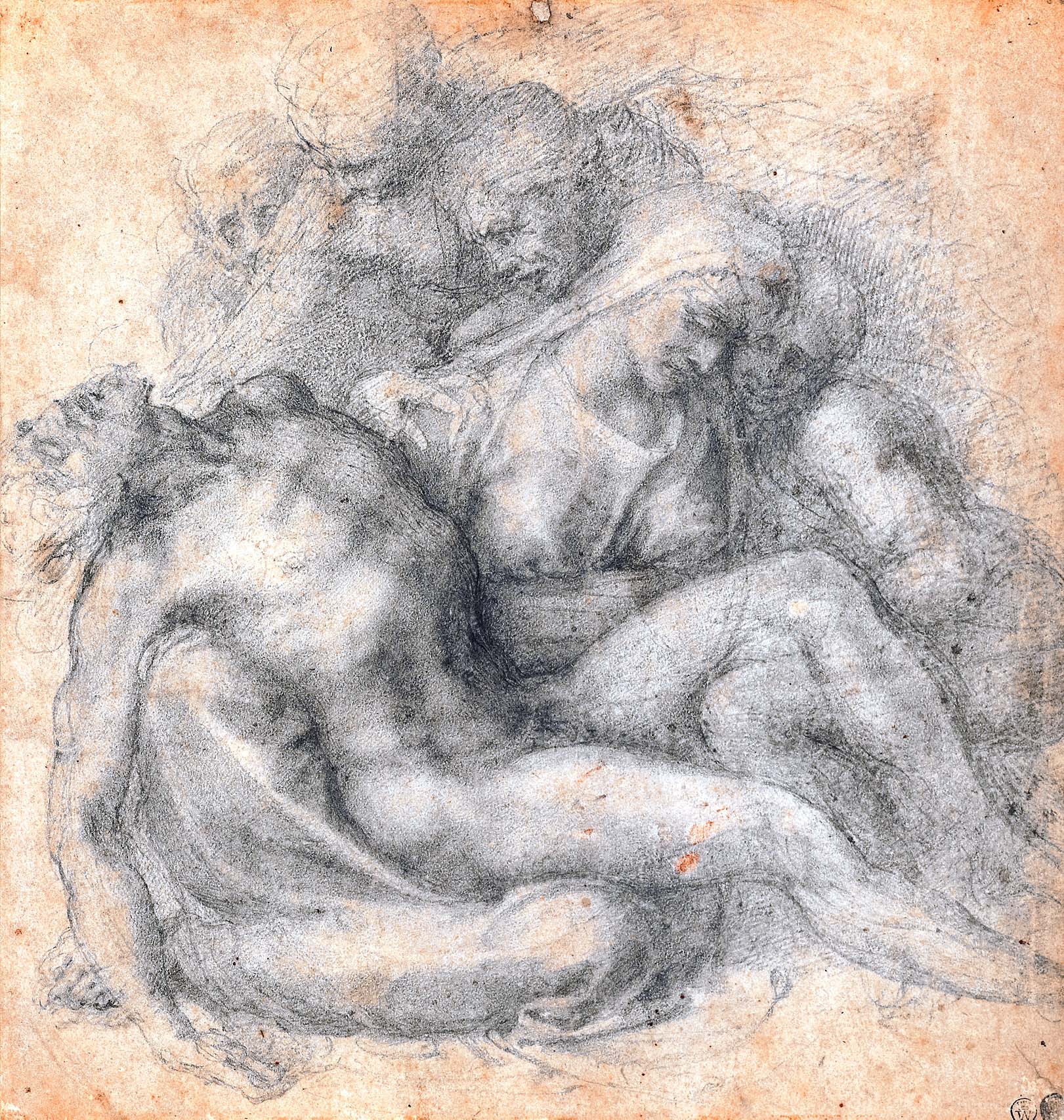

The studies for “The Last Judgement” and other drawings show that his power had not diminished. In some ways, these drawings are more daring than any he had attempted before. Multiple drawings appear on the same sheets and the positions of the figures: falling, fallen, twisting in space, suffering for sins and experiencing ecstasy, suggest Michelangelo’s interest in more extreme corporeal expressions of the seminal events in Christian and classical theology. It’s art as transubstantiation. Yet, it seems to derive directly from the revival of antiquity that characterizes the Renaissance. “The Fall of Phaeton” — Phaeton, son of Apollo, struck down by Zeus when he failed to control the chariots of the sun and scorched the earth — echoes “The Last Judgement,” while the torso of Christ on the Cross is congruent with the agony of the Greco-Roman marble, “Laocoön.” Then, the magnificent, larger-than-life cartoon, Epifania, shows Mary as a mother rather than a goddess, her left hand between her legs, emphasizing the association of Christ with the womb — and, by extension, the body — of the Virgin.

But the nude figures of “The Last Judgement,” expressions of the artist’s belief that flesh burdened the soul, didn’t appeal to everyone. Nor did Michelangelo’s abiding friendship with poet Vittoria Colonna and the group that were called i spirituali, intellectuals who advocated for faith and predestination as a cure for what they saw as a wealth and indulgence-based church. At the same time, Martin Luther and others were raising the spirit of Protestantism, and the notions of i spirituali were seen as dangerously close to Lutheran. Michelangelo now found his art caught between the high humanism of earlier decades and the stirrings of the Counter-Reformation, complete with inquisitions and an equation of nudity with obscenity. In a supreme irony, even the notorious pornographer, Aretino, called for censorship of the fresco, though Michelangelo’s refusal to give Aretino a drawing may have had something to do with it.

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), “Pietà,” circa 1535, black chalk on paper. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

Accordingly, and for many years, other artists draped away Michelangelo’s figure work. Had “The Last Judgement” and his other Pauline frescos been executed by a lesser artist, they might well have been destroyed and the artist, well, executed. In another medium, verse, Michelangelo would also be caught between love — especially in his sonnets dedicated to Tommaso de’Cavalieri — and the Christian desire to be liberated from earthly desire. As his friendship with Vittoria Colonna grew, his verse took on what might be called a more neo-Platonic view, having more to do with the failure of striving, even in his own art, and the yearning of the soul for oneness with God.

Michelangelo finished the tomb of Pope Julius II and his drawings became designs for paintings executed by others, including “The Cleansing of the Temple” — and the exhibition features Michelangelo’s wonderful highly wrought drawing on glued-together scraps as well as Marcello Venusti’s painting, complete with Middle Eastern columns that twist like Michelangelesque bodies.

But Michelangelo wasn’t through. Not by half. At 70, he was given the task of completing the design for and overseeing the construction of St Peter’s Basilica as well as a number of other structures in Rome, including the Palazzo Farnese. I mention this because a quote in the exhibition catalog, referring to the Michelangelo’s revisions of earlier architects’ designs for the windows of the palazzo, takes me right back to the “Slaves”: “But in Michelangelo’s hands, the result was startlingly new, a synthesis of erudite antiquarianism and resourcefulness: in the simplest but most effective change, he enlivened the pilasters of his models with half-pilasters either side, creating an animated effect of forms seeming to emerge from the wall and recede into it again…” (pp. 175).

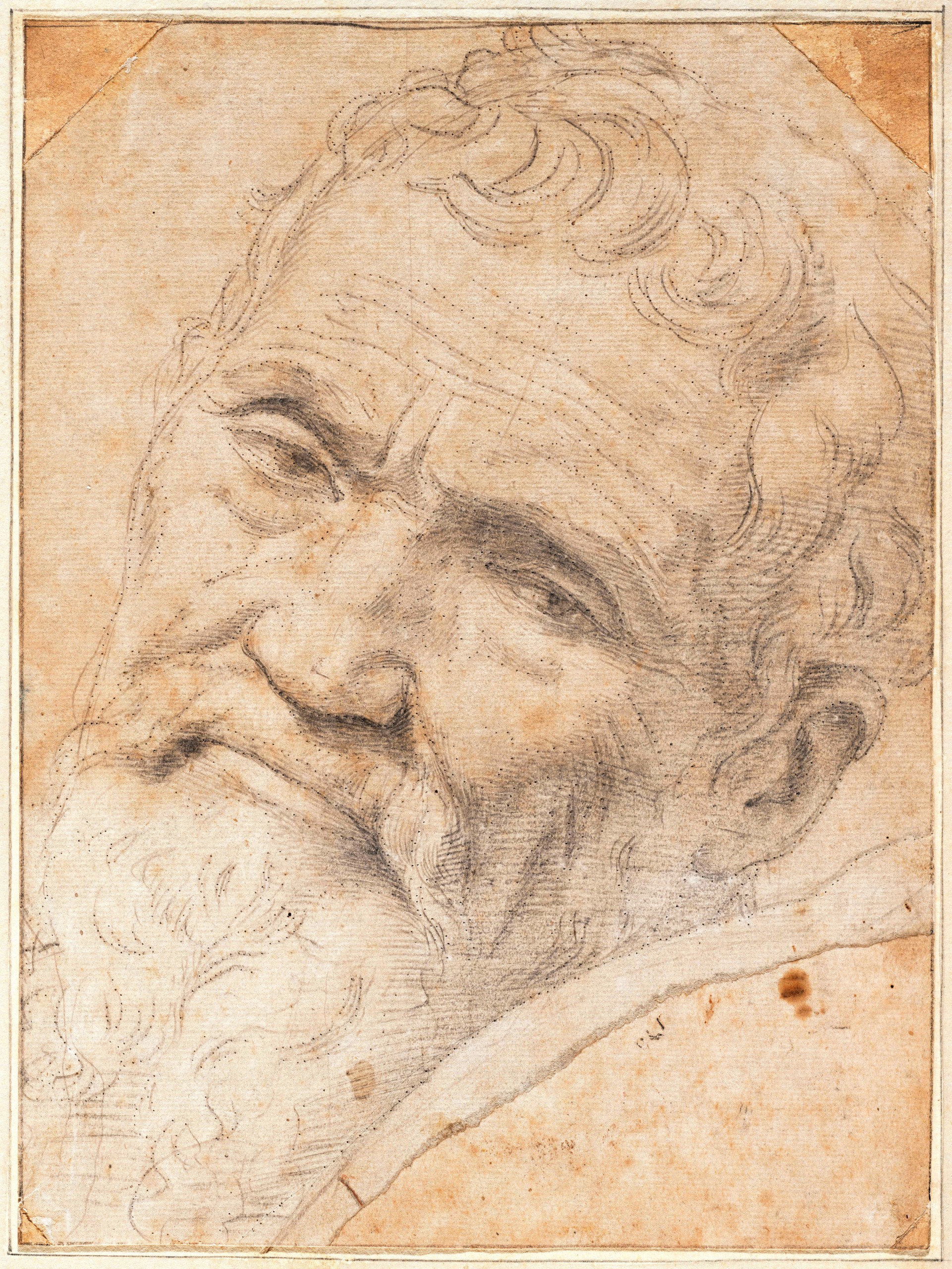

Daniele da Volterra, Cartoon for a portrait of Michelangelo, 1550-55, leadpoint and black chalk. ©Telyers Museum, Harlem, the Netherlands.

Emerging and receding. Caught between. Animated. Vasari and many other scholars over the ensuing centuries have written that Michelangelo sought to “liberate the forms imprisoned in the marble.” Looking again at the “Slaves,” at the carved flesh and the uncarved block — which is body and which is soul? And when, in the late works, are flesh and soul one? Are they ever, or are we all meant to remain unfinished?

Thinking about this makes me reconsider the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and the famous passage in the fresco: God releasing Adam into being. Recent scholarship has opined that God might well be Michelangelo, thinly veiled. God as artist, as artist who is never quite satisfied — “non finito” — I wonder if, in fact, God on the Sistine ceiling isn’t caught between letting go and reaching out to grab Adam and get him back so he can work on him just a little bit more.

I fear that the writing about “Michelangelo: The Last Decades” will focus on Michelangelo’s genius, his late spirituality, and his resilience and vigor in the face of aging, as if he is an ad for a wonder drug featuring a man with a good head of wavy gray hair — and an even better stock portfolio — who stops jogging, smiles at the camera, and says, “I’m living my best life.” In truth, Michelangelo was caught up in his times, caught between powerful forces, caught between this life and the next, between body and soul, and yet his art still managed to thread needle after needle. He died in his bed. The apotheosis began immediately, as did the circling of collectors. “Michelangelo: The Last Decades” isn’t about spirituality, charisma or resilience. It’s visceral.

“Michelangelo: The Last Decades” will be on view at the British Museum through July 28.

The British Museum is on Great Russell Street. For information, www.britishmuseum.org.