By Madelia Hickman Ring

NEWTOWN, CONN. — The latest volumes of the Chipstone Foundation’s Ceramics in America (CIA) and American Furniture (AF) have rolled off the presses and, in a perennial Antiques and The Arts Weekly tradition, we gave each of them a once-over. Both are noteworthy in that they can be considered transitional works: both represent collaborative efforts by outgoing editors Robert Hunter (CIA) and Luke Beckerdite (AF) alongside their incoming replacements, Ronald W. Fuchs II and Martha Willoughby, respectively.

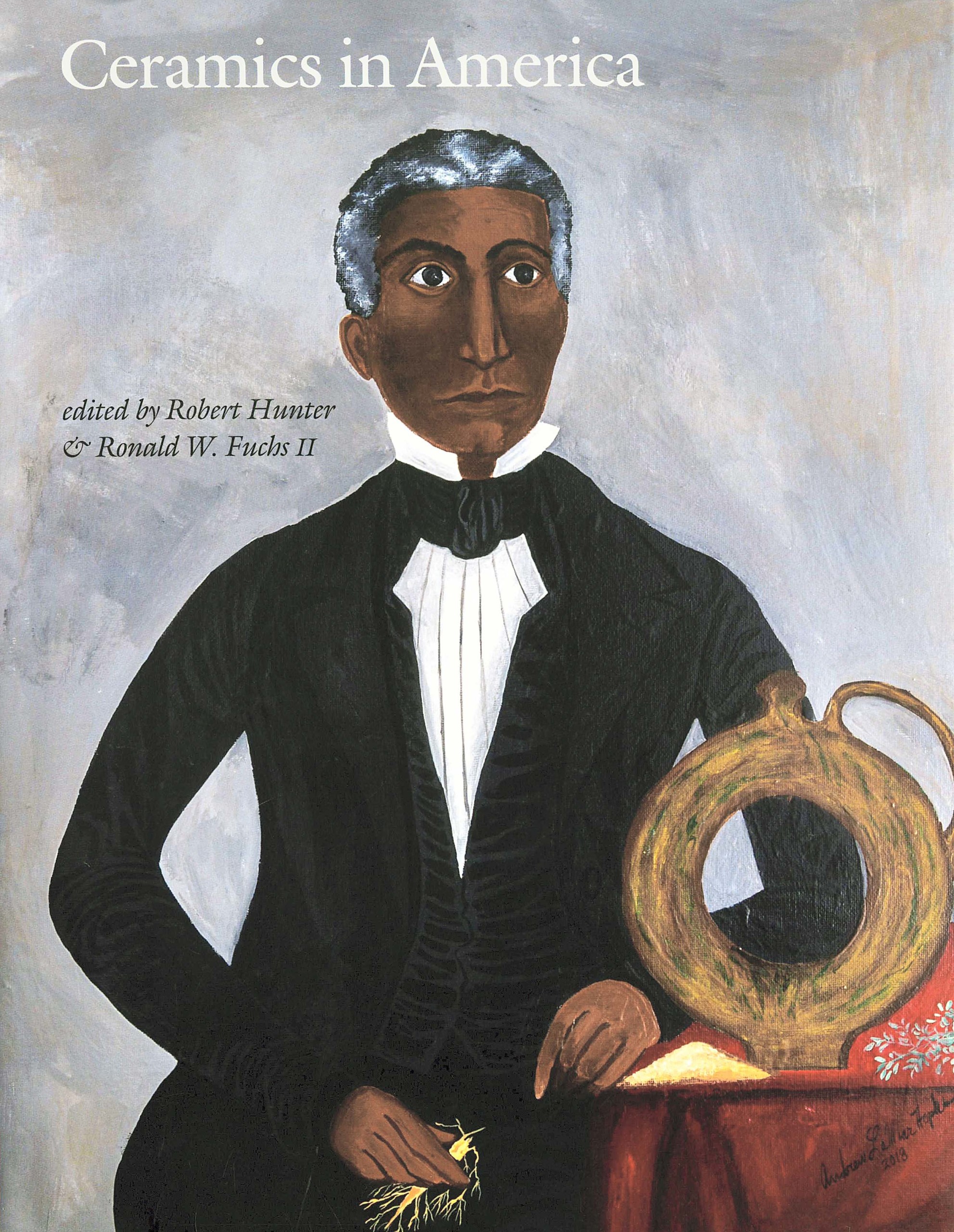

Ceramics in America. Edited by Robert Hunter and Ronald W. Fuchs II, with contributions by Robert Hunter, Elyse D. Gerstenecker, Kurt Ross, Stephen C. Compton, W. Ross Ramsay, Howell G.M. Edwards, Errol Manners, Ashley Howkins, Daniel S. Sousa, Niel Ewins, James D. Kaufman, David Mack, Ellen J. Lippert, Elizabeth Donison, Ned Rose, Angelika Kuettner, Amanda Creekman Isaac, Captain Charles T. Creekman and R. Ruthie Dibble. Published by The Chipstone Foundation, Milwaukee, Wis., 2023, 222 pp, $65, hardcover.

In addition to his comments in an editorial statement, Hunter penned a lengthy introduction to the book that read more like a farewell sendoff than anything else but which also serves to give brief insights to the contents of the tome.

The volume’s cover image — an “imagined” portrait of Dr Peter Davis by contemporary New Orleans folk artist Andrew Hopkins – tees up the first article in the book: Hunter’s “Southern Hoodoo and the Dr Peter Davis Ring Bottle.” The history of the bottle, the context in which it and others were made and its connections to hoodoo (voodoo) rituals are discussed in this lively read.

Hunter was a contributing writer — alongside Elyse D. Gerstenecker and Kurt Ross — for the volume’s second article, “At the End of a Rope: A Stoneware Jar and Political Frustration.” Focusing initially on a stoneware jar, made circa 1861 in Richmond, Va., with pro-Confederate writing and imagery, the authors’ commentary evolves into a robust discussion of Civil War-era stoneware made in Virginia and the various political imagery decoratively employed.

A lengthy article by Stephen C. Compton on potter John Wesley Carpenter (North Carolina, 1842-1913) follows. In it, Compton explores Carpenter’s role within the greater traditions of stoneware pottery in the South after the Civil War, first in North Carolina, then in Virginia.

Scientific analysis was employed extensively by W. Ross Ramsay, Howell G.M. Edwards, Errol Manners and Ashley Howkins in their article based on an Eighteenth Century porcelain snuff box originally attributed as made in the Italian factory of Doccia. Subsequent examination of the glaze and shape allowed a reattribution to the Bow porcelain manufactory.

A child’s plate acquired by Historic Deerfield in 2020 that is transfer-printed with scenes of how sugar was produced and featured three presumably enslaved Black figures, attributed to John Carr & Sons, North Shields, Northumberland, England, circa 1854-8161, is the subject of Daniel S. Sousa’s article, “‘From Death to Life:’ Slavery and Emancipation in the British West Indies as Revealed on a Child’s Plate.” Originally considered to convey an anti-slavery message, Sousa argues it is more symbolic of a society that retained pro-slavery sentiments at a time when emancipation was becoming part of daily life.

This theme carries through to Neil Ewins essay, “Hidden Histories: The Case of Elijah Lovejoy and the Production of Anti-slavery Ceramics.” Reverend Lovejoy (1802-1837) was the proprietor of an abolitionist newspaper in Alton, Ill., who was murdered by a pro-slavery mob in 1837, an event that was widely publicized in print and, eventually, as decorative motifs on Staffordshire wares. Ewins himself shares his disappointment that there was no evidence to support the hoped-for hypothesis that wares celebrating Lovejoy were made to benefit anti-slavery organizations; they were, it seems, more likely purchased by consumers to “silently preach abolitionism” without actively practicing it.

A portrait of American abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879) adorns a lead-glazed earthenware vase, made by the Chelsea Keramic Art Works in Chelsea, Mass., around 1879. James D. Kaufman notes such representation of an abolitionist, though frequently employed by British potters, was an infrequent phenomenon in the United States.

In his article, “Earth, Fire, and the Abolitionist: The Emancipation of Clay for Social Change,” contemporary Black potter and art teacher David Mack reflects on race as a critical market marker. He observed that once he started throwing Heritage Face Vessels, pots with the sculpted — and sculptural — faces of distinguished people of color, he was both connecting to a past Black cultural generation but also became a minority innovator.

Ellen J. Lippert explores six unglazed clay coin-like tokens made by George Ohr (1856-1917) that stand out from his otherwise vast, colorful body of work. Bearing no maker’s mark but clearly mold-made — itself a distinguishing characteristic from his tradition of hand-thrown or singular objects — the tokens are notable for their obscene sexual messages. Lippert notes the context in which they were made — the precise dates of their manufacture, whether they were sold or for how much they cost, if they were popular or who purchased them — is still unknown but proposes they survive as a souvenir of prominent sites of fantasy, including the World Fairs of America’s Gilded Age.

A fragmented English Delft plate unearthed at an Eighteenth Century Virginia tavern, which has Asian-inspired scenes, is explored by Elizabeth Donison, Ned Rose and Angelika Kuettner, who find parallels with similar plates excavated near Williamsburg, Va. A larger discussion on the prevailing taste and styles of contemporary consumers followed.

Two Chinese porcelain punch bowls bearing the pseudo-armorials of American naval hero Thomas Truxtun (1755-1822) and George Washington that are decorated on the interior with similar images of a full rigged Eighteenth Century naval frigate inspires a closer look at wares made to celebrate Truxtun and his captaining of the Constellation in 1799 and capturing the French frigate, L’Insurgente. Authors Amanda Creekman Isaac and Captain Charles T. Creekman argue the bowls were made as political gifts in support of the newly founded US Navy.

Closing out Ceramics in America — and coming full circle from its start with hoodoo ceramic traditions — is R. Ruthie Dibble’s article, “Family Reunion: The Clay Sculptures of Babette Wainwright.” A contemporary Wisconsin potter born in Haiti, Wainwright (b 1952) explores her heritage through a careful use of Haitian tools, materials and iconography.

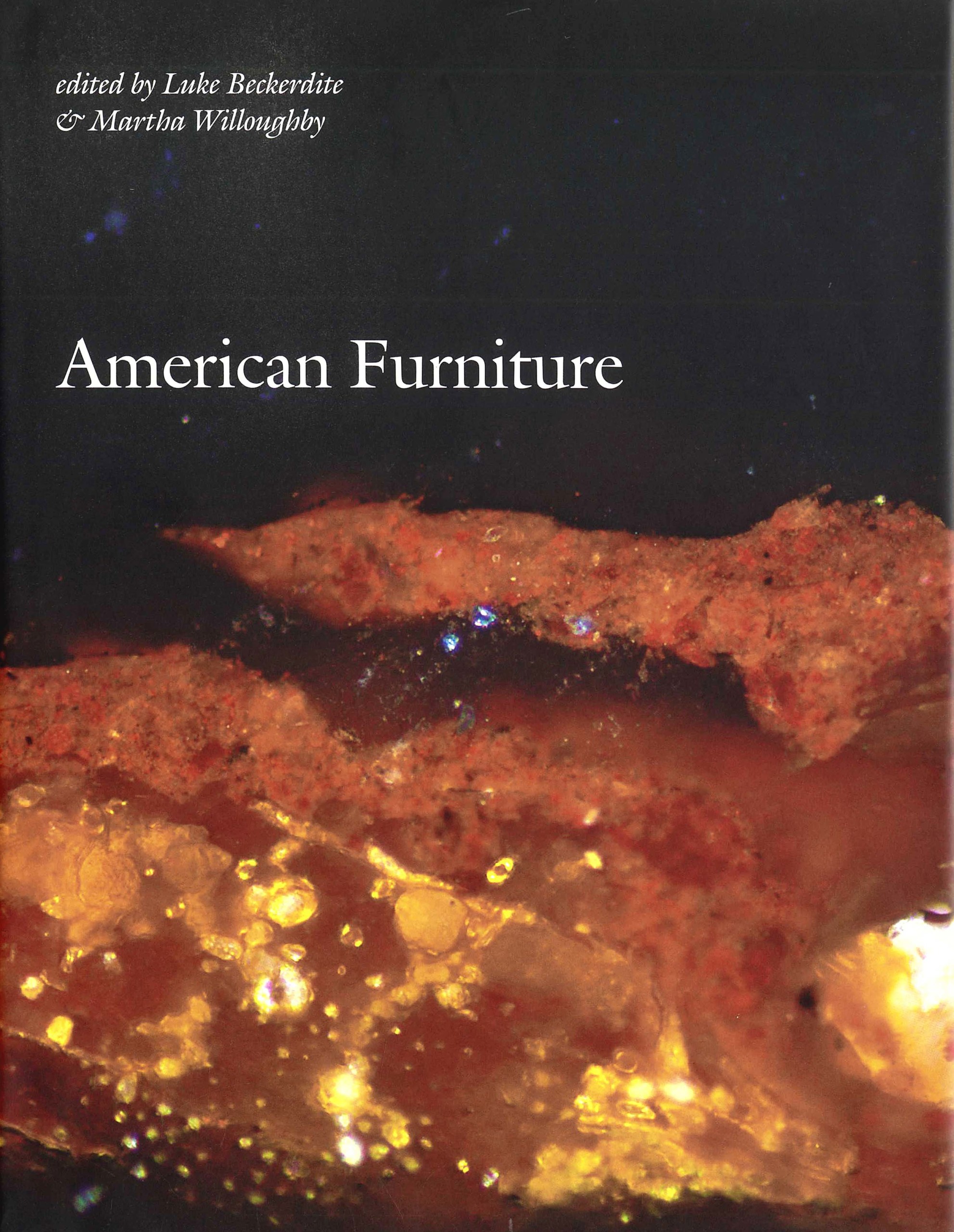

American Furniture. Edited by Luke Beckerdite and Martha Willoughby, with contributions by Diane C. Ehrenpreis, Emilie Johnson, F. Carey Howlett, James Gergat, Susan L. Buck, Nancy Goyne Evans and Gerald W.R. Ward. Published by the Chipstone Foundation, Milwaukee, Wis., 2023, 214 pp., $65, hardcover.

No lengthy editor’s note prefaces this volume, in which a significant percentage of pages are dedicated to furniture owned or designed by Thomas Jefferson.

Kicking off the journal is a lengthy article by Diane C. Ehrenpreis that explores a packing list, written on August 31, 1790, by Thomas Jefferson, itemizing furnishings he purchased for a dining room, library and study from New York cabinetmakers while he was living there as secretary of state. Ehrenpreis notes his spending spree was prompted in part to furnish those rooms he considered most important for diplomacy and because of a dinner he had with James Madison and Alexander Hamilton. What began as an assessment of Jefferson’s possessions in transit evolves into an exploration of his furniture and the greater New York City context in which it was made.

In the second article, Emilie Johnson examines the design and construction of a sofa Jefferson commissioned by New York cabinetmaker Thomas Burling in 1790, one of the pieces was not only on the inventory list discussed in the previous article but one that — because of its close associations with Jefferson and long history at Monticello — make for an important history.

The transition to F. Carey Howlett’s essay on Jefferson’s revolving chair, which is deemed “probably the best known of his furnishings at Monticello…a nearly unique example of American furniture” is seamless. Also commissioned from Burling in 1790, furniture scholars have previously drawn design comparisons and influences by French fauteuil de bureau. Though Howlett notes that Jefferson would have seen the French model while in Paris, there is no evidence that these visits influenced Burling’s design.

A writing box, made in the Philadelphia workshop of Benjamin Randolph in 1775, and a rotating Windsor armchair, also made in Philadelphia circa 1785-95, were both owned by Jefferson and are the subject of James Gergat’s essay. In it, he discusses the form and construction of both and the documentation surrounding each.

Susan L. Buck takes a more literal “deep dive” into Jefferson’s revolving Windsor armchair in her article, discussing cross section microscopy paint analysis of samples taken from protected areas that would be less likely to have traces of later surfaces. Her research reveals that a chair that has been through “substantial refinishing” and which now appears to be an all-over brown-painted chair was once cream-colored with grain painting. She proposes that traces of original red paint discovered on the writing arm suggest it may have been a later addition.

In 1964, graduate student Nancy Goyne Evans (then Nancy A. Goyne) published an article in the first issue of Winterthur Portfolio titled “Francis Trumble of Philadelphia: Windsor Chair and Cabinetmaker.” The Windsor scholar revisits this topic with James Gergat in “The Decline and Rise of Francis Trumble: A Philadelphia Success Story,” in which the two incorporate not only her more recent scholarship but his findings as well.

American Furniture concludes in its time-honored tradition of featuring a bibliography on recent writing on American furniture compiled by Gerald W.R. Ward.