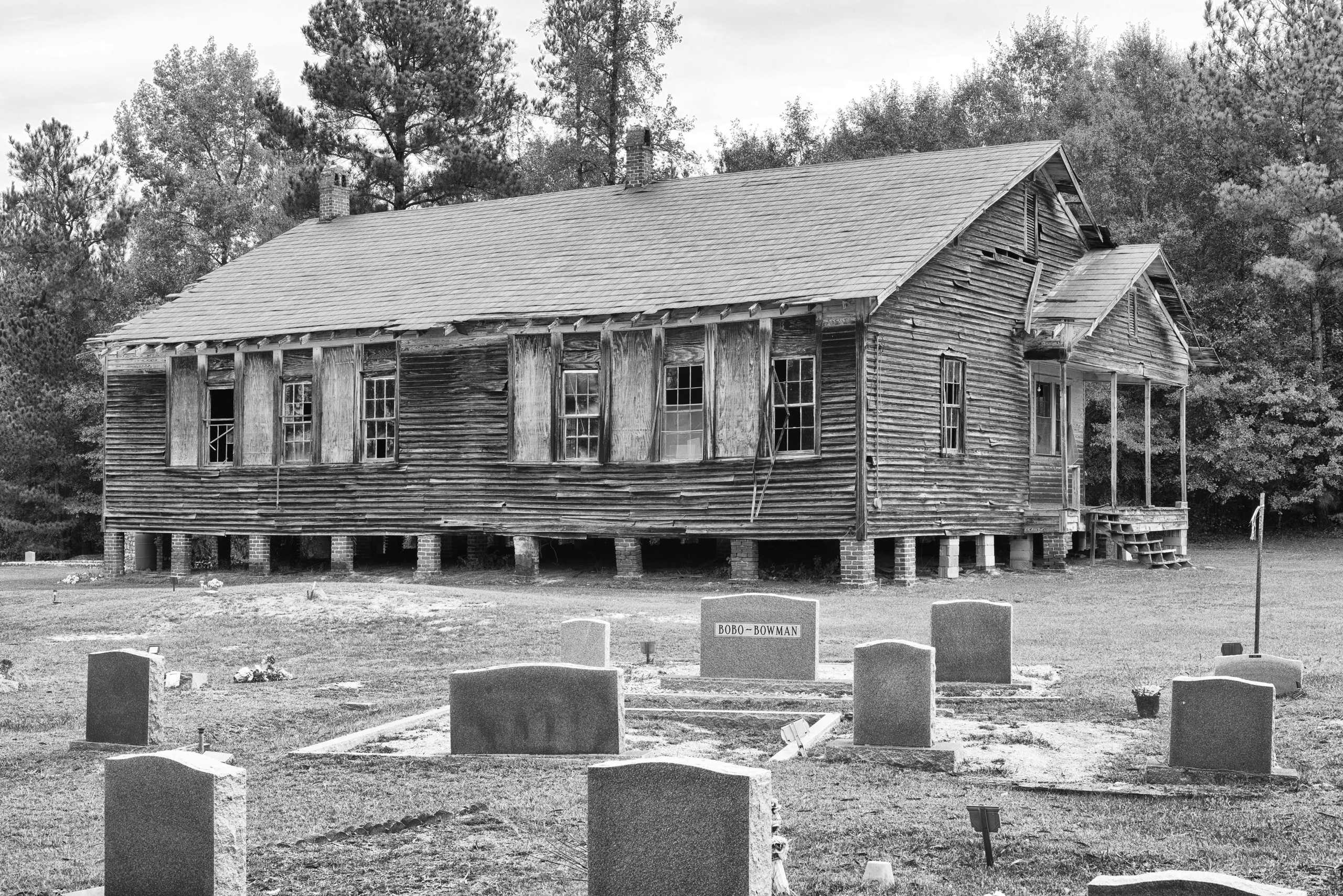

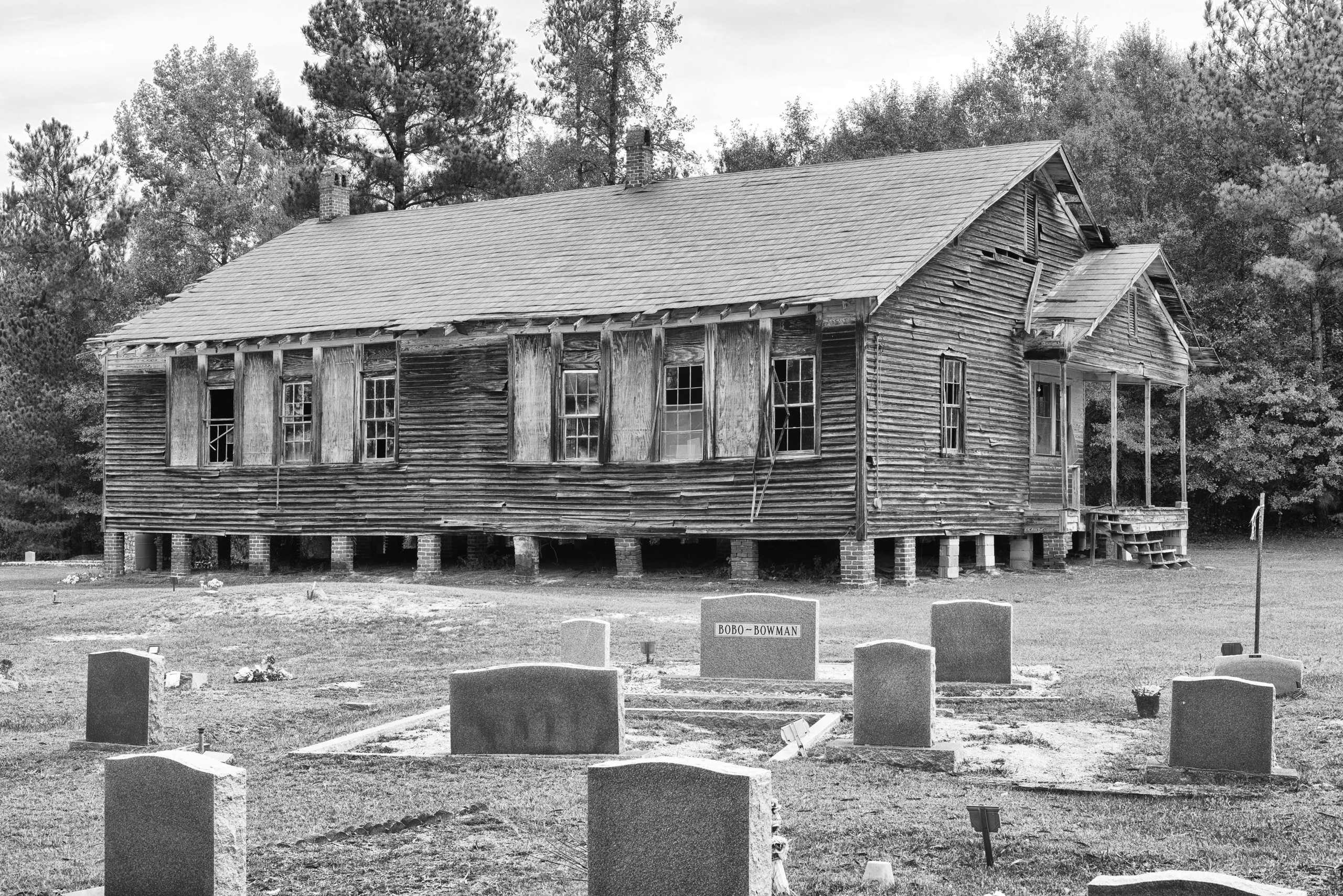

“Hannah School, Newberry County, South Carolina 1925-1960s.” ©Andrew Feiler.

By James D. Balestrieri

RICHMOND, VA. — Although it is currently being tested by the cycles of violence that have led to the war in Gaza, the relationship between Jewish and African American activists and leaders is historically a very strong one, as evidenced by “A Better Life for Their Children: Julius Rosenwald, Booker T. Washington, and the 4,978 Schools That Changed America,” on view through April 20, 2025, at the Virginia Museum of History & Culture in Richmond. Born into enslavement in Virginia, Booker T. Washington achieved fame for his undying efforts to improve education for Black Americans. After founding the Tuskegee Institute, he became a trusted confidant of President Theodore Roosevelt and many other prominent politicians, educators and, importantly, captains of industry and business. In 1911, Washington met Julius Rosenwald, a businessman whose innovations had transformed Sears, Roebuck & Company into the world’s largest retailer. Together, Washington and Rosenwald crafted and realized an educational vision whose reverberations in American political and cultural life resonate to this day.

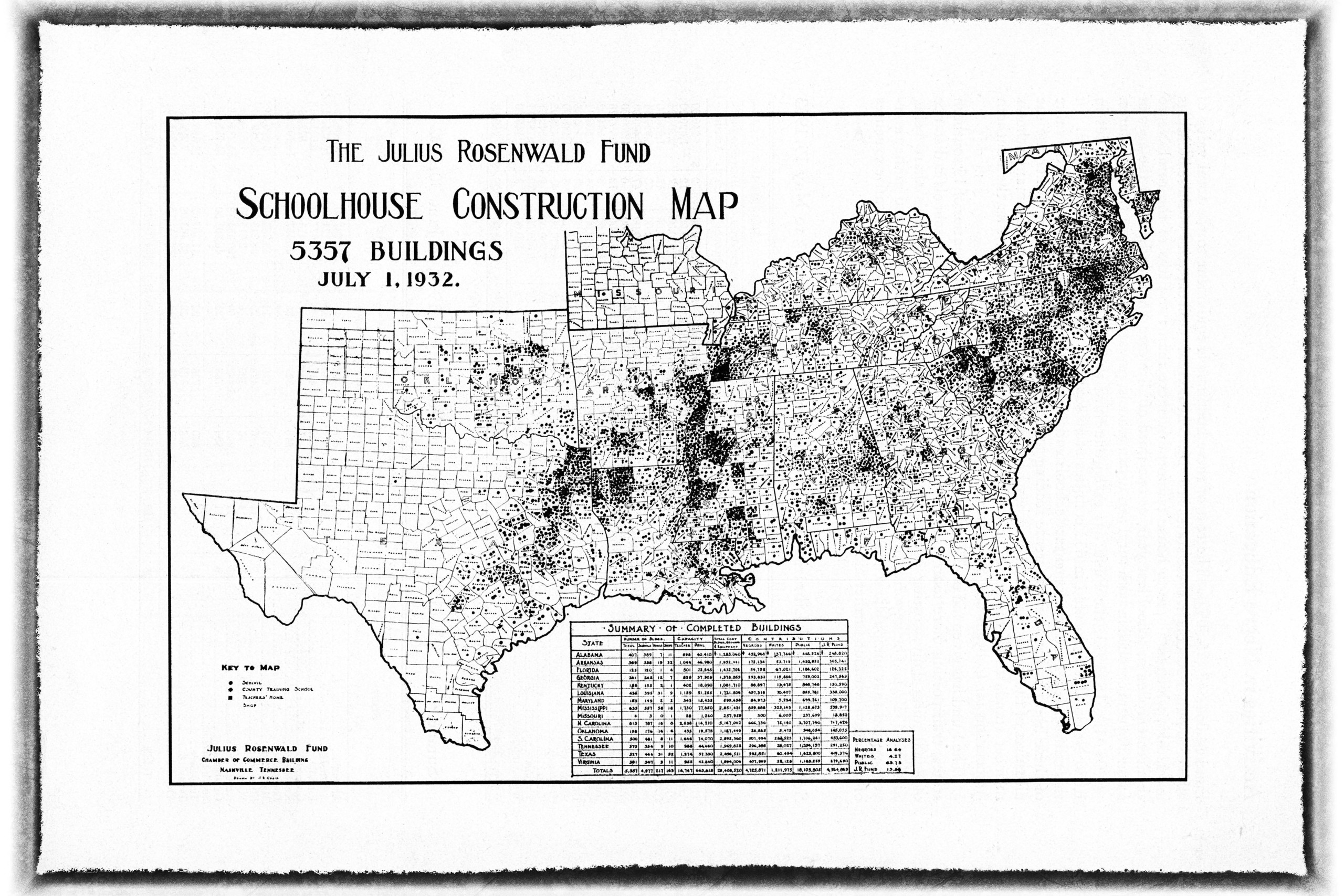

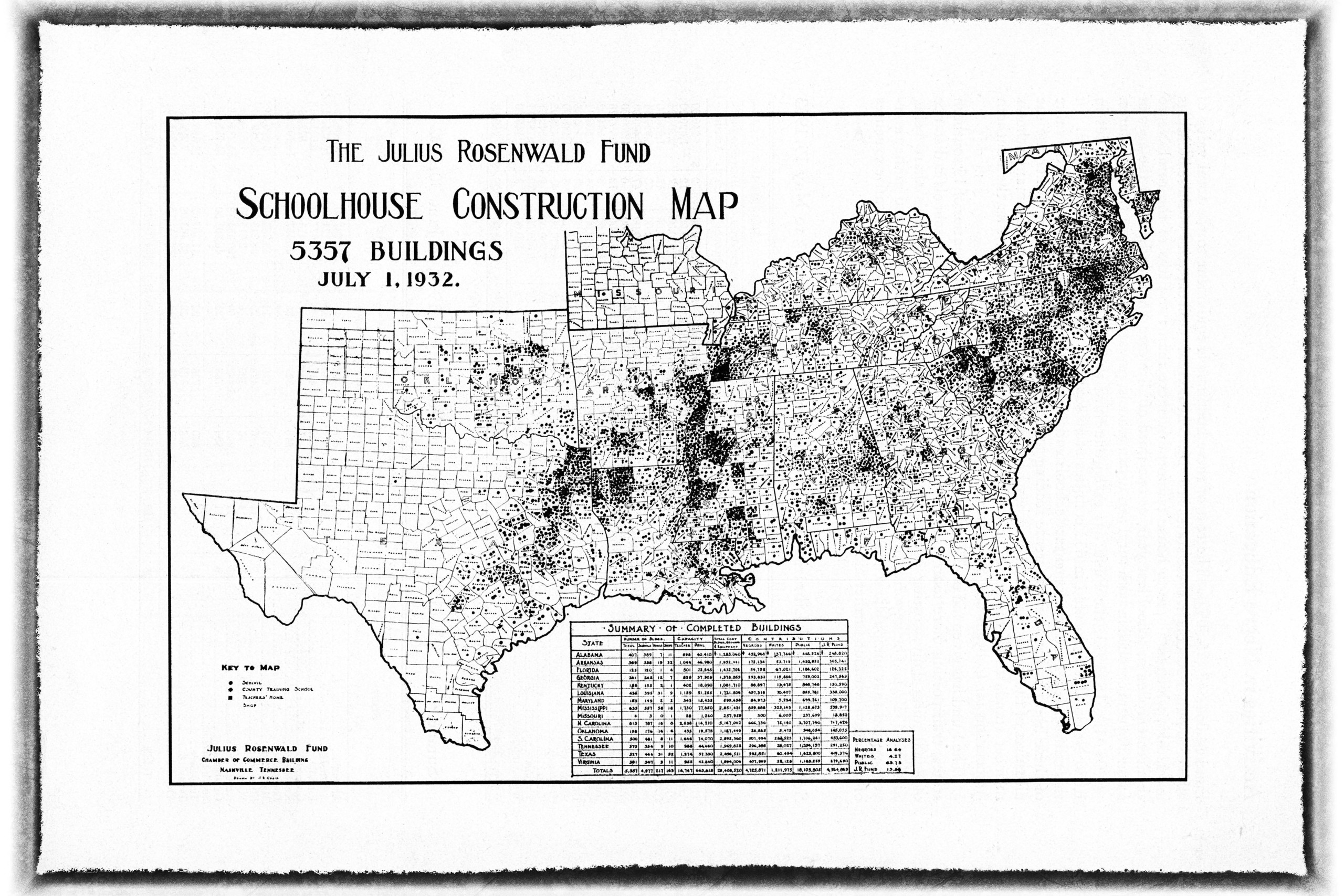

At the time, where there were few schools for Black children at all in the American South, the buildings themselves were often run-down, ramshackle affairs in underfunded, segregated school systems. Black communities supplemented these where they could, holding classes in homes and churches. But Rosenwald’s interest in philanthropy dovetailed with Washington’s vision for a large-scale program of school construction and an idea was born. To leap ahead, from 1912 to 1932, the Rosenwald schools program built 4,977 schools for Black students in 15 Southern and border states. Since desegregation, the Rosenwald Schools have suffered from neglect; perhaps one-tenth of the nearly 5,000 structures still stand. To preserve the history and document the story, award-winning photographer Andrew Feiler — a Jewish American and native of Georgia — crisscrossed the South, logging more than 25,000 miles, photographing 105 schools and tracking down “dozens of former students, teachers, preservationists and community leaders in all 15 of the program states.”

Valerie Coleman & Marian Coleman, curators, descendants of Rosenwald School builder Webster Wheeler. ©Andrew Feiler.

Three things at least must be made clear about the Rosenwald Schools. The first is that Rosenwald himself contributed about one-fourth of the funds to build the schools. The other three-fourths came from local governments and Black communities who, as the essay, “The Remarkable Story of Rosenwald Schools” states, “held bake sales, barbecues and rallies to raise money; they also donated land, building materials, and labor toward their matching requirement” (Virginia History & Culture, Winter-Spring 2024, pp. 5). The second is that other Black leaders criticized the Rosenwald Schools because they perpetuated segregation. “They [Washington and Rosenwald] focused on providing educational opportunities — particularly vocational training — rather than trying to dismantle segregation. This stance put Washington at odds with other Black leaders, such as W.E.B. DuBois, who were demanding civil rights and equality” (Virginia History & Culture, Winter-Spring, 2024, pp. 6). The third is that the impact of these schools can hardly be overstated. A glance at Feiler’s portrait and a consideration of its title, “John Lewis – Civil Rights Leader, US Congressman, Rosenwald School Former Student,” reveals this titanic American figure in all his complexity. Above the elegant suit and tie he wears, beside the rich textures of the leather couch in what is presumably his office, Feiler captures the topography of Lewis’ activism, written in the deep lines on his face, in the half-stare, half-squint and the slight cock of his head that peers out at the viewer and says, “And what ‘good trouble’ have you been up to lately?” Behind him, like crowded memories blurred only by time, photographs of other, earlier days fill the walls. That this all began in a Rosenwald School, and that other Black leaders such as Maya Angelou and Medgar Evers attended similar schools, attests to the power of the program and the influence of its graduates.

I imagine that the concept of mass producing schoolhouses intrigued Julius Rosenwald. After all, you could buy a prefabricated kit home — and just about anything else — from the famous Sears catalog that made the company the Amazon of its time. “The Rosenwald program provided architectural plans for schools of various sizes designed by Tuskegee architects. These buildings were generally modest, wood-framed structures with large windows to afford lighting and air circulation in areas that often lacked electricity. The designs also called for movable room partitions to maximize flexibility. Indeed, many schools also functioned as community centers” (Virginia History & Culture, Winter-Spring 2024, pp. 7). In many ways, the Rosenwald Schools were way ahead of their time, anticipating the open classrooms and interest in connecting school interiors and the outside world that characterize contemporary educational theory. Indeed, they might well serve as models for schools in rural — and urban — areas around the world today.

“Restored Classroom, Pine Grove School, Richland County, S.C., 1923–1950,” 2018, archival pigment print, 20 by 30 inches. ©Andrew Feiler.

Feiler’s “Restored Classroom, Pine Grove School – Richland County, S.C., 1923-1950” acts as a window into the Rosenwald School past. Light floods in from the right onto the desks, restored but still worn with decades of use. The grain of the polished pine floorboards mirrors the slats of the painted ceiling. In the corner, the old stove stands. This was a warm, bright place, a safe place to learn. The American flag is small, stuck behind a corner of the blackboard that hangs empty, as if awaiting the scrape of chalk. The globe is small and stands atop a bookshelf with too few books. America, the world, education — these are in reach but precarious and aspirational. At left, a second room looks as though it could quickly be separated from the main class, dividing grade from grade or activity from activity. On the wall, we see a quilt celebrating the 2019 restoration of the Pine Grove School, with a photograph of Washington and Rosenwald walking together in its center.

It’s tempting to concentrate solely on the fascinating history and the architecture of the schools, but Feiler’s project, coupled with his artistry, mark his photographs, and the exhibition itself, as a unique interpretation of history. His images are the lens — the aesthetic, the art — through which we see the Rosenwald Schools. First of all, the images are in black and white. Black and white is a choice, an aesthetic all its own. It’s the choice of the documentarian and the journalist, suggesting a desire to convey a certain historicity. After all, the great images of the struggle for racial equality, images of strife, of dignity, of beauty, are almost all monochrome. Black and white, of course, also holds up a mirror to the question of race in America that underpins the whole exhibition. It is as if Feiler wants us to see the Rosenwald Schools — the need for them, their success, the disrepair they have fallen into, and their restoration, both physically and in our minds and history — as part of a continuum in a fight that, yes, has produced progress but is still far from over.

Julius Rosenwald Fund schoolhouse construction map, Fisk University Archives, ©Andrew Feiler.

Some of the schools, especially those that served as technical and trade schools and community hall, such as “Rosenwald Hall, Seminole County, Okla., 1921-1966” have withstood time and the elements and seem to need only a bit of tender loving care to bring them back to life. In other images, however, including “Hannah School, Newberry County, S.C., 1925-1960s,” Feiler shows us the schools as he discovered them, fallen into disrepair, falling down. But Feiler, ever on the lookout to add meaning to his work, shows us the newer headstones that stand in opposition to the school in the foreground of the image. The dilapidated school — perhaps intentionally — recalls the kinds of structures that the Rosenwald Schools replaced while the headstones suggest, perhaps, the meaningful lives of some of the students who attended this very institution. Above all, this image, and others like it, are calls to action, calls to preserve these important parts of our history before time erases them.

Many of Feiler’s images are of empty schoolrooms and buildings in unpeopled landscapes. At first, this seems counterintuitive if what the exhibition intends is to communicate the vibrancy of the Rosenwald project. But there is something in them that makes me think back to the great French photographer Eugène Atget (1857-1927), whose photos of Paris, the circuses and carnivals in particular, when they were empty, devoid of the humanity that brought them to life, somehow fills them — in my mind, at any rate — with the very spirit of the laughter, amazement and joy that is absent from the images themselves. Sometimes ghosts are louder than people.

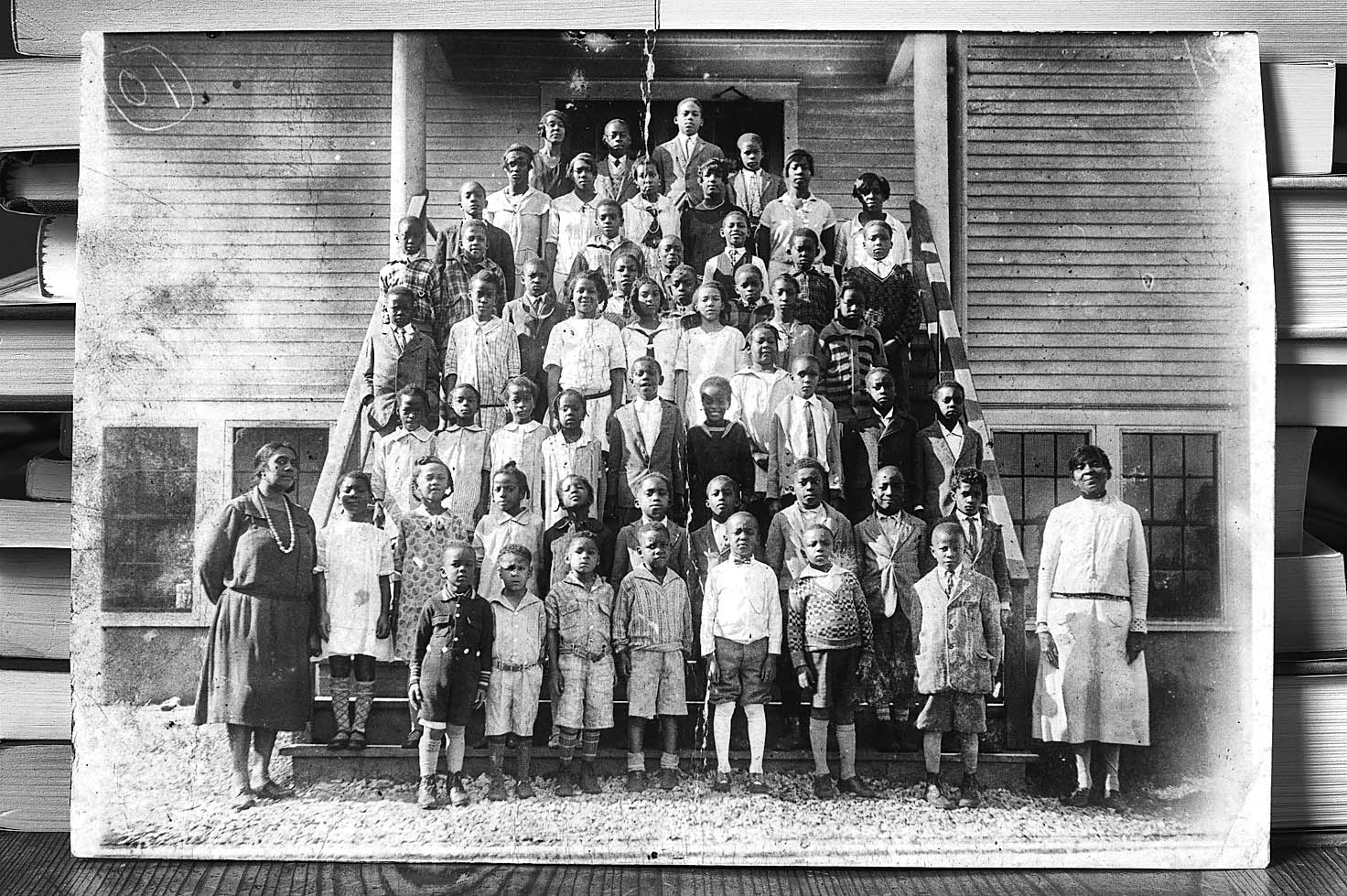

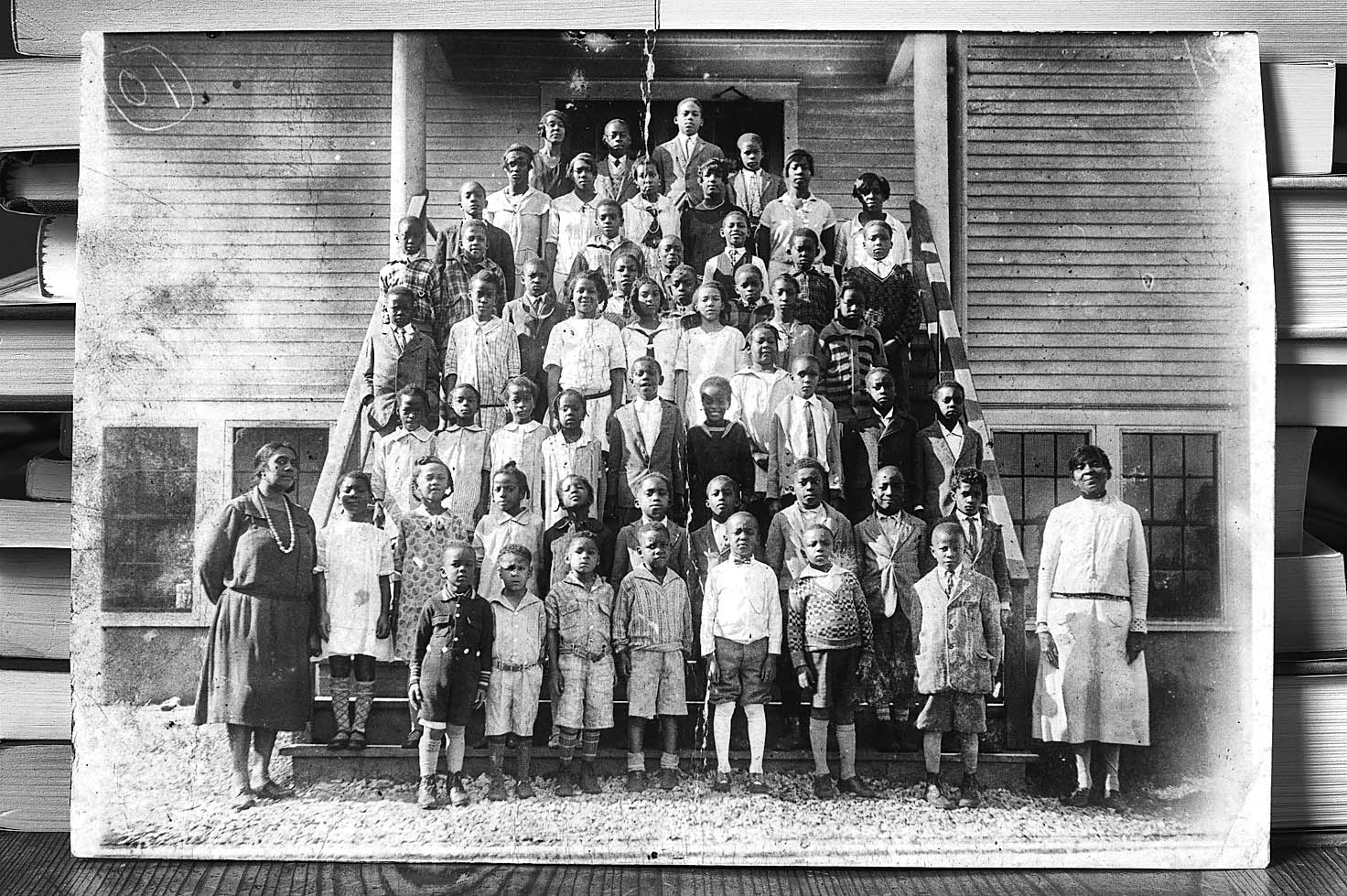

“Students and Teachers at Jefferson Jacob School, 1920s,” The Filson Historical Society, 2019, archival pigment print, 20 by 30 inches. ©Andrew Feiler.

The counterpoint to these photos is, of course, the people themselves — the old photos of classes on the steps of the Rosenwald Schools. What you see in the eyes and postures of the students and faculty is a kind of pride mixed with an energy yearning to break free. And then, in Feiler’s images of former students and teachers, images like “Ellie J. Dahmer, Widow of Slain Civil Rights Leader, Rosenwald School Former Student and Teacher,” the sheer resilience of those who ran with the opportunities afforded them by the Rosenwald Schools shines through. The title of the work leads us to the history of Ellie Jewel Davis Dahmer and her late husband, Vernon F. Dahmer Sr, to their efforts to secure voting rights for Black Americans and their advocacy for education, and to Vernon Dahmer’s tragic death at the hands of vigilantes, but say you didn’t know all that, say you only had this image. You know you are in the presence of a formidable woman, someone who exudes experience and strength, someone whose story would be well worth listening to.

Should the powerful relationship between Black and Jewish Americans require repair, Andrew Feiler’s photographs in “A Better Life for Their Children: Julius Rosenwald, Booker T. Washington and the 4,978 Schools That Changed America” would be an excellent reminder of the successes of the past and an excellent starting point for the projects of the future.

The Virginia Museum of History & Culture is at 428 North Arthur Ashe Boulevard. For information, 804-340-1800 or www.virginiahistory.org.