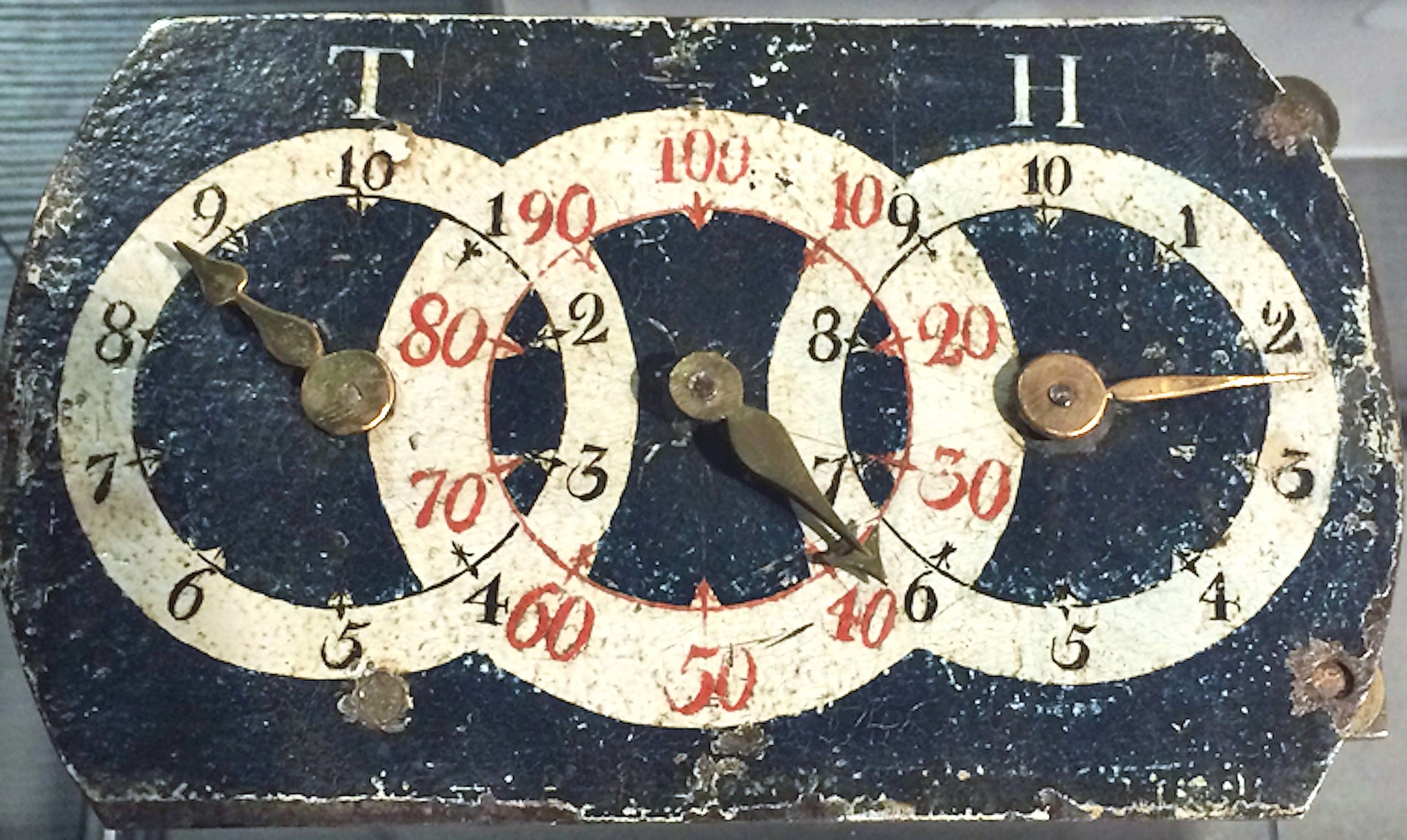

This dial accompanies a clock in the collection of the American Philosophical Society that was passed down through the family of Benjamin Franklin’s daughter and was given as a gift of Junius S. and Henry S. Morgan in 1954. It is one of just four Duffield clocks that has a spherical moon in the dial arch. Collection of the American Philosophical Society. John Wynn photo.

By Madelia Hickman Ring

PHILADELPHIA — “Collectors of antiques are likely to think of clocks as furniture rather than as timekeepers. They pay considerable attention to the case, but little or none to the mysterious mechanism within, though that is actually the clock, and in most cases the only part of the whole thing made by the man whose name appears on the dial. Cases were made by cabinetmakers, dials were usually imported, and the product of the clockmaker was the hidden work. It is these complex devices that concern the true clock collector, and the story of their development, and the growth of the clockmaking industry in America, is a fascinating one indeed.”

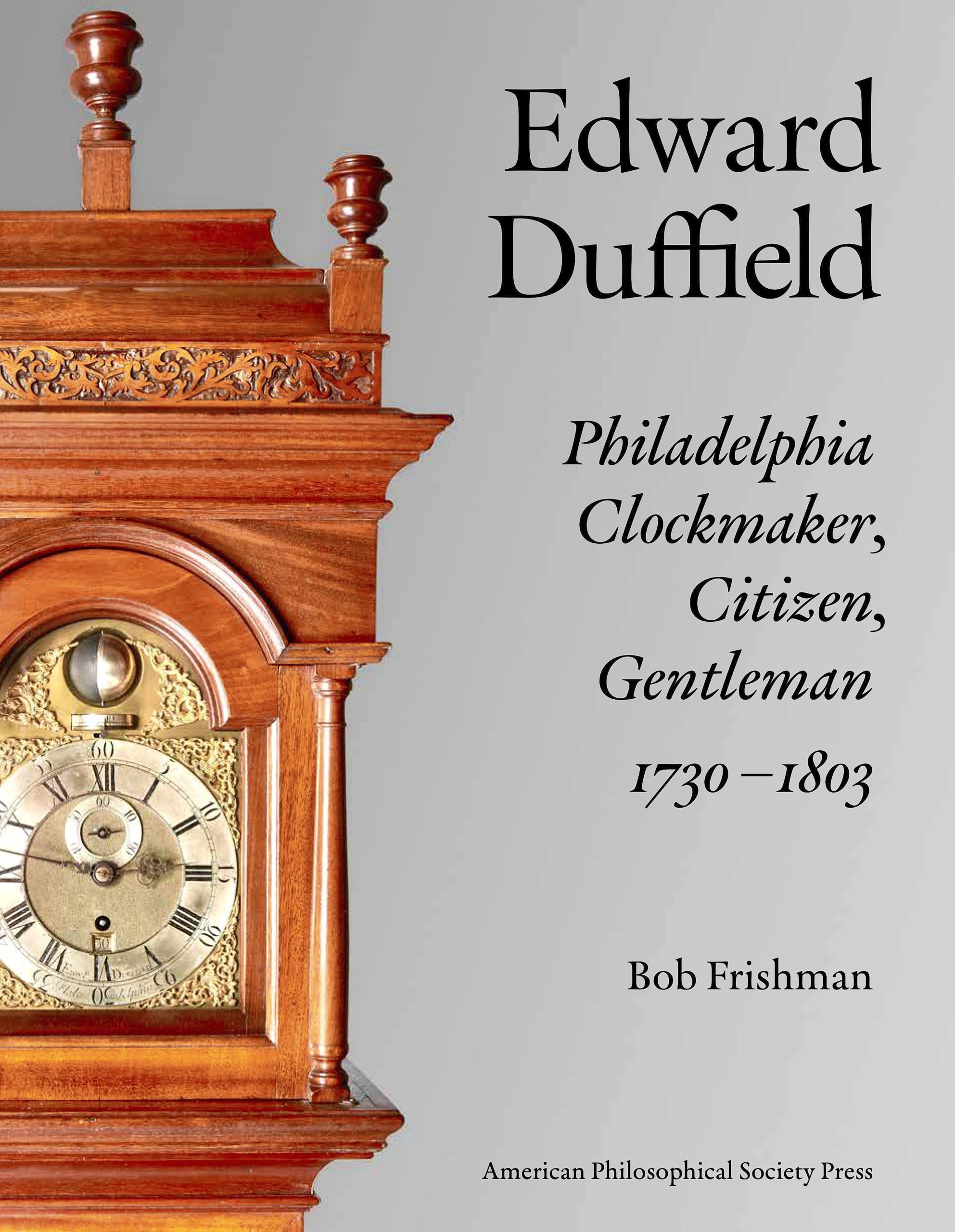

That paragraph, penned in June 1952 by The Magazine ANTIQUES editor Alice Winchester, was used by author Bob Frishman to introduce readers to Edward Duffield: Philadelphia Clockmaker, Citizen, Gentleman 1730-1803, which was recently published by the American Philosophical Society (APS) in Philadelphia. Prior to its publication, scholarship on the clockmaker was scant and early: two articles by George Eckhardt, in 1959 and 1960, and Ian Quimby’s unpublished 1963 Winterthur thesis. The torch wasn’t picked up until 2006, when David Sperling wrote an article on Duffield for the January 6, 2006, issue of this publication and another that appeared in the October 2006 issue of the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors’ (NAWCC) Bulletin.

Edward Duffield: Philadelphia Clockmaker, Citizen, Gentleman 1730-1803, by Bob Frishman, with preface by Edward W. Kane and foreword by Jay Robert Stiefel. Published by the American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, 2004. Black and white and color, 242 pp, $60, hardcover.

Frishman took up the task more than four year ago, at the request of Winterthur trustee and horology philanthropist Edward W. Kane, who also previously underwrote books on clockmakers David Rittenhouse and William Claggett. Kane not only financially supported the publication of this book but also penned its preface. Frishman is quick to point out that he received no financial compensation from either Kane or APS for writing the book, nor will he receive royalties from its sale (those will go to APS).

As a clockmaker, Duffield was unique for a few reasons. He was born into a family of means, owned many properties and was not dependent on his clockmaking skills to provide for himself or his family. He stands alone in his family for his interest in horology: there are no clockmakers in the generations that preceded or followed him. He is not known to have served an apprenticeship though in mid-Eighteenth Century Philadelphia, there were no guild or trade restrictions requiring one. Frishman speculates that Duffield — like many intellectually curious and wealthy young men who were his contemporaries — was attracted to the costly timepieces his family had the means to own. Lastly, Duffield advertised his services infrequently and there are no extant account books or ledgers to document his horology business.

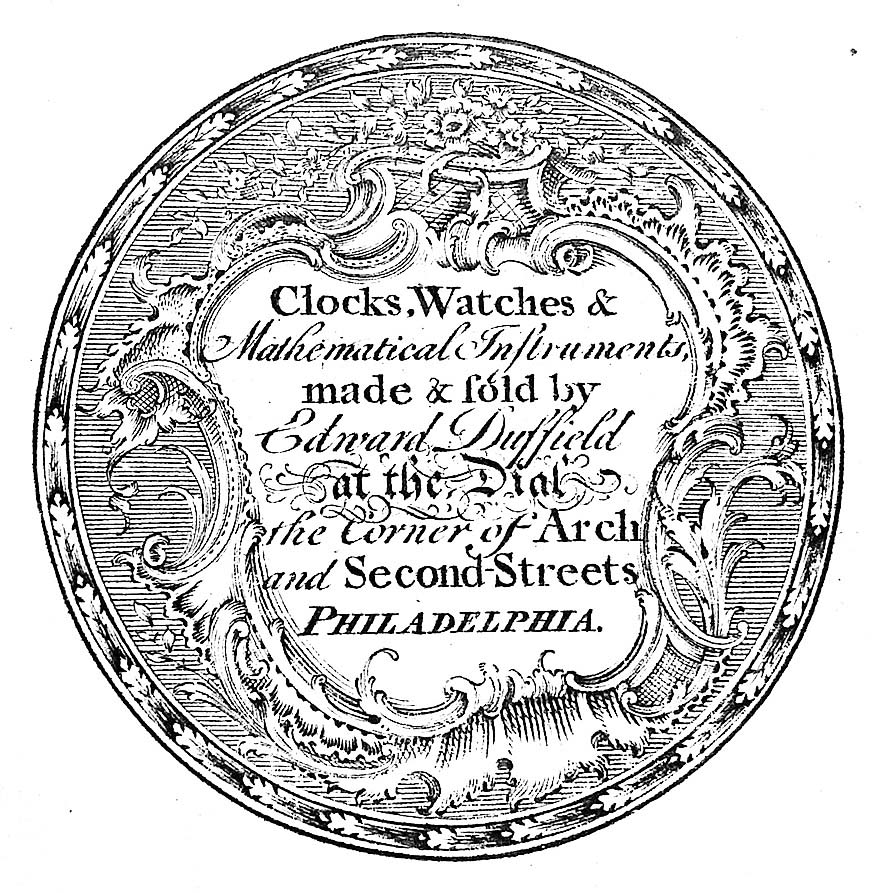

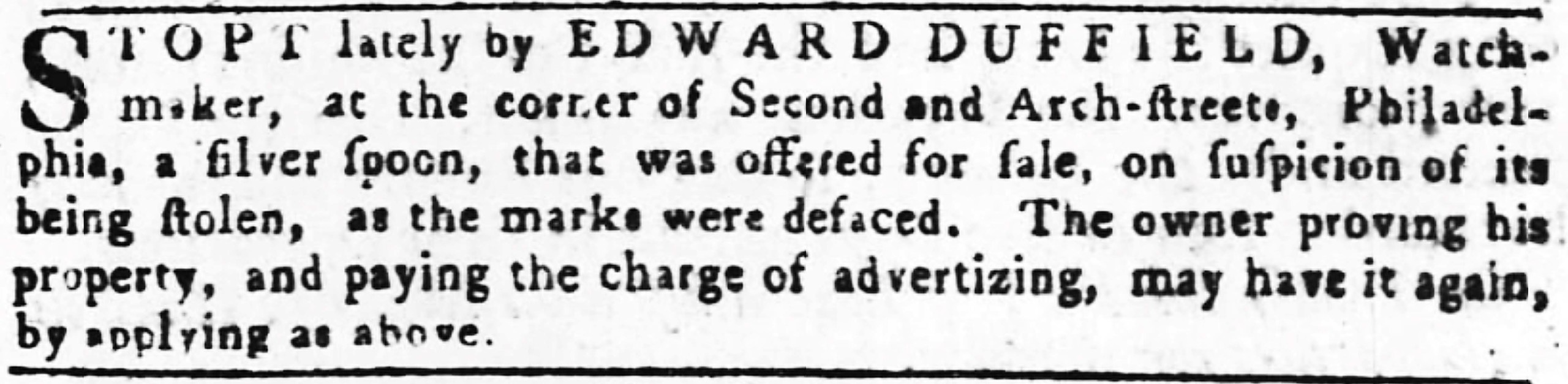

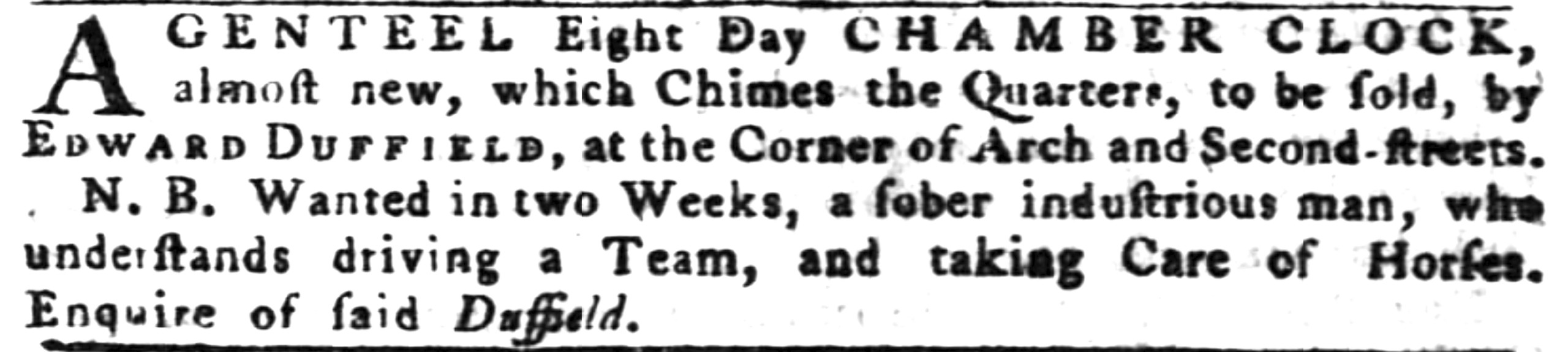

The practice of advertising by Philadelphia clockmakers is one Frishman explores in detail. The first time Duffield’s name and identity as a watch maker appears in the Philadelphia papers — he advertised in 1751 as a purveyor of food — was in 1756 when he advertised for the return of a stolen silver spoon. The only known undated watch paper, which is in the Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera at Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library and which would have been pressed into the back of a pocket-watch case, would have been one way for him to spread the word of his trade. The only time Duffield advertised his services — for a “genteel” clock he did not make — was for a chamber or table clock that appeared in the November 8, 1770, issue of Pennsylvania Gazette.

Advertisement placed by Edward Duffield on page 4 of the November 8, 1770, issue of Pennsylvania Gazette. Image courtesy American Antiquarian Society, via Genealogy Bank.

Duffield and his family were close friends with Benjamin Franklin and his family. Frishman, who believes Franklin was a strong influence on his younger friend’s choice of career and its success, devotes an entire chapter to their relationship which began between Franklin in-laws and Duffield’s parents before Edward was born — the families lived next door to each other — and lasted for decades, ending with Duffield being one of three executors of Franklin’s will in 1790 (he was also named as executor in Franklin’s first draft of his will, in 1757). The two men shared not just an appreciation for artisans making things by hand but also a love of horology.

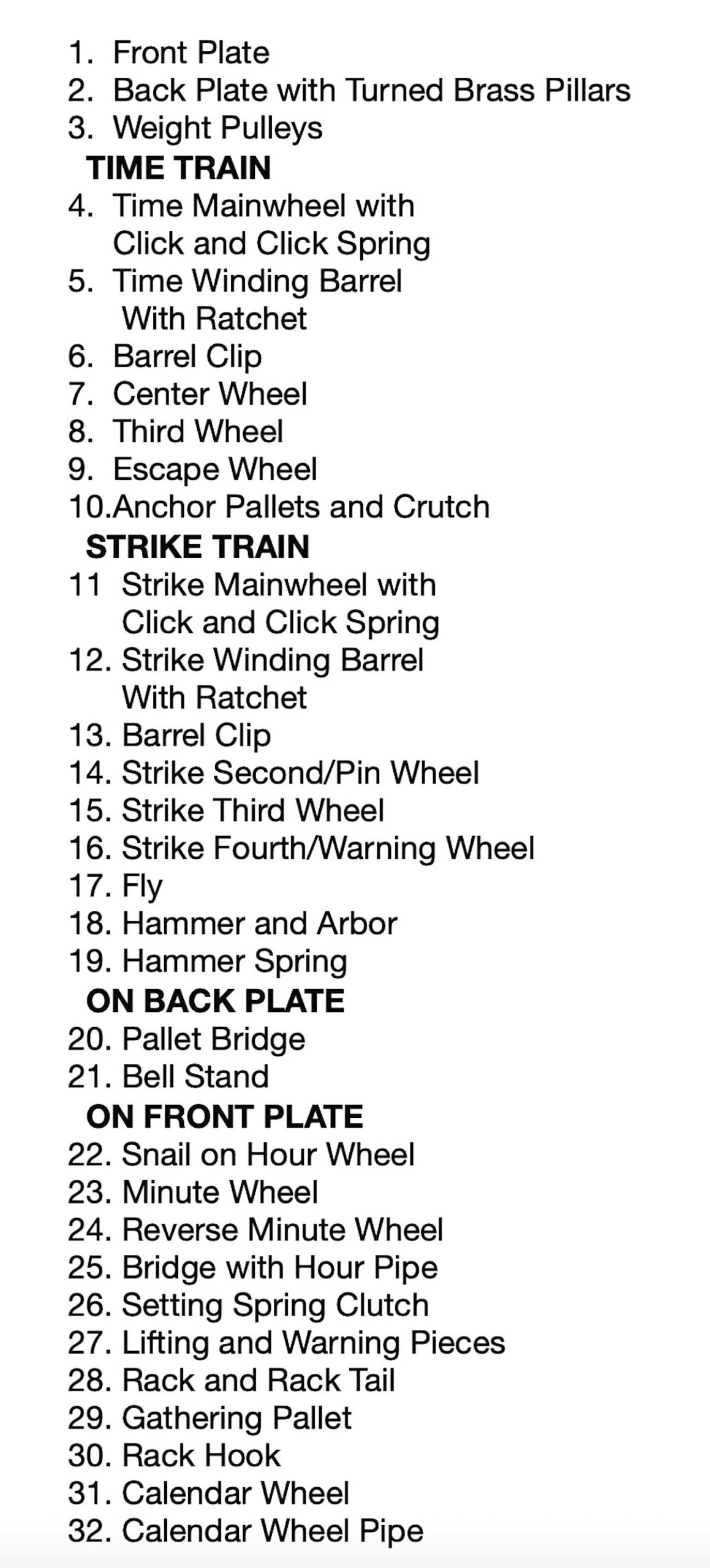

Frishman is clear to note that while Duffield made many of the clocks he sold and repaired both clocks and watches, it does not mean that he made watches, which could be acquired already assembled from English counterparts. Indeed, with interest in buying and owning British-made goods, no economic reason to “buy American” and given the extensive time and cost required to make watch parts, Duffield would have had little incentive to do so. To circle back to Alice Winchester’s comment at the beginning of this story, Duffield — like contemporaries in America and England — housed his clock works in wooden cases made by skilled woodworking cabinetmakers.

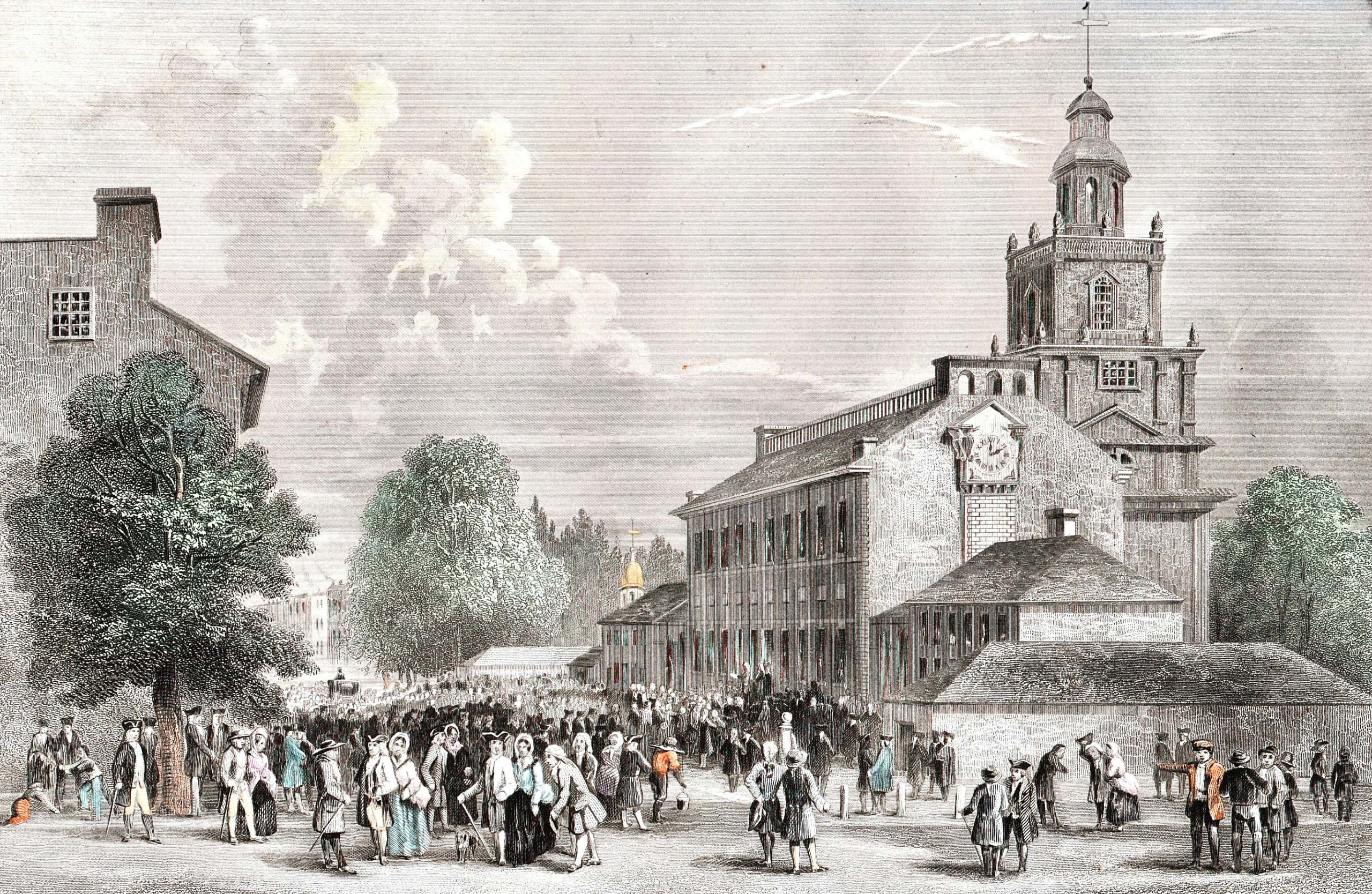

Interestingly, for a dozen years, Duffield had the honor of being the keeper of the large clock atop the Pennsylvania State House (now Independence Hall).

Possible portrait of young Edward Duffield, location unknown, Courtesy of Frick Art Reference Library, New York City.

Compared to contemporaries such as David Rittenhouse, who made clocks with additional complicated elements, Duffield’s clocks are conservative in their complexity. However, four Duffield clocks that feature a rotating spherical lunar indicator in the dial arch are unusual and possibly unique to him. Frishman knows “of no others made in America at that time, and a small number of English predecessors have a different system for turning the little metal moon.”

Antiques and The Arts Weekly asked Frishman if, in the course of his research, there were any surprises or revelations that dispelled any preconceptions he had when he began.

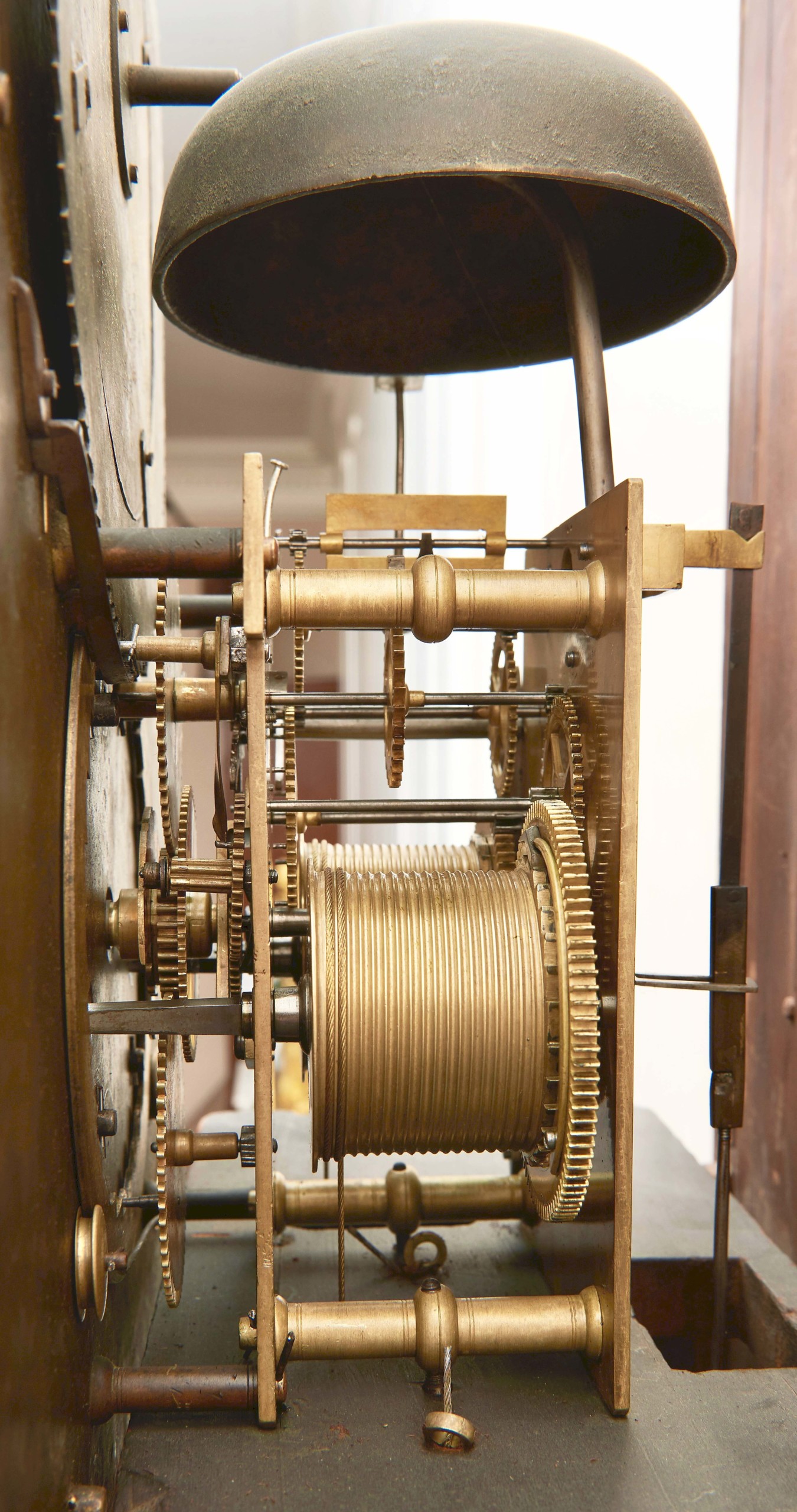

“While I understood from decades of servicing antique clocks that the movements and dials of such Eighteenth Century tall clocks are quite similar, I thought that perhaps I would discover more significant differences among them. I wanted to claim that Duffield, and perhaps his Philadelphia contemporaries, were somehow working at a higher level. However, while of consistent fine quality — evidenced by the fact that many of them still tick and strike flawlessly today — this was not the case.”

Tall case mahogany clock with a single-train movement commissioned of Edward Duffield in 1769 by the American Philosophical Society, for the purpose of timing the transit of Mercury; Duffield completed the works in three weeks and received £15.17.6 for it. Collection of the American Philosophical Society, John Wynn photo.

Duffield’s profession as a clockmaker ended in 1775 when he leased his shop to clockmaker John Lind, and retired to Benfield, his country estate in Moreland Township, Philadelphia County; in 1779, he appears as a “farmer” on the tax list. There could have been several motivating factors for this life change: at 45 years of age, he may have grown weary of toiling at a workbench, or anticipated what the oncoming political turmoil that led to the American Revolution would do to his trade in British-made parts. Not least, he would have faced growing competition in a city that, according to the 1774 tax list, reported 30 percent of its properties owners as craftsmen of some kind, including many newly arrived horologists.

“Every biographer’s fear is that a new trove of primary materials surfaces shortly after publication, but I will consider that a good thing,” Frishman admits. For the book, he drew from existing primary source material and Duffield’s surviving clocks and watches. The catalog of Duffield’s clocks and instruments includes every documented example, even where the location is presently unknown; a total of 71 objects are included. Frishman hopes more may surface in the future.

Not only does Frishman’s book detail the context in which Duffield worked and the professional craftsmen he interacted with but also gives a comprehensive account of the social spheres Duffield inhabited. He mingled regularly with the city’s non-Quaker elite as a vestryman and warden of the prestigious Anglican Christ Church, and he had many other important civic duties.

Photograph of Duffield Homestead, Benfield, A History of the Townships of Byberry and Moreland, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania by Joseph C. Martindale and Albert W. Dudley, 1901, p. 303. Courtesy of Internet Archive.

A transcription of his 1803 will — and estate inventory — provide a late-in-life snapshot of a man whose limited production stands on a par with some of Philadelphia’s greatest clockmakers.

With so many of Duffield’s clocks in permanent museum or private collections around the United States, Frishman regrets that an exhibition on the clockmaker is unlikely to be pulled together. He is already at work on his next project — a comprehensive study of the Mulliken family of Massachusetts clockmakers that will be published by the Concord Museum; a late 2026 publication date is anticipated, as is a probable exhibition shortly thereafter.

Editor’s note:

Edward Duffield: Philadelphia Clockmaker, Citizen, Gentleman 1730-1803, by Bob Frishman, with preface by Edward W. Kane and foreword by Jay Robert Stiefel. Published by the American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, 2004. Black and white and color, 242 pp, $60, hardcover.