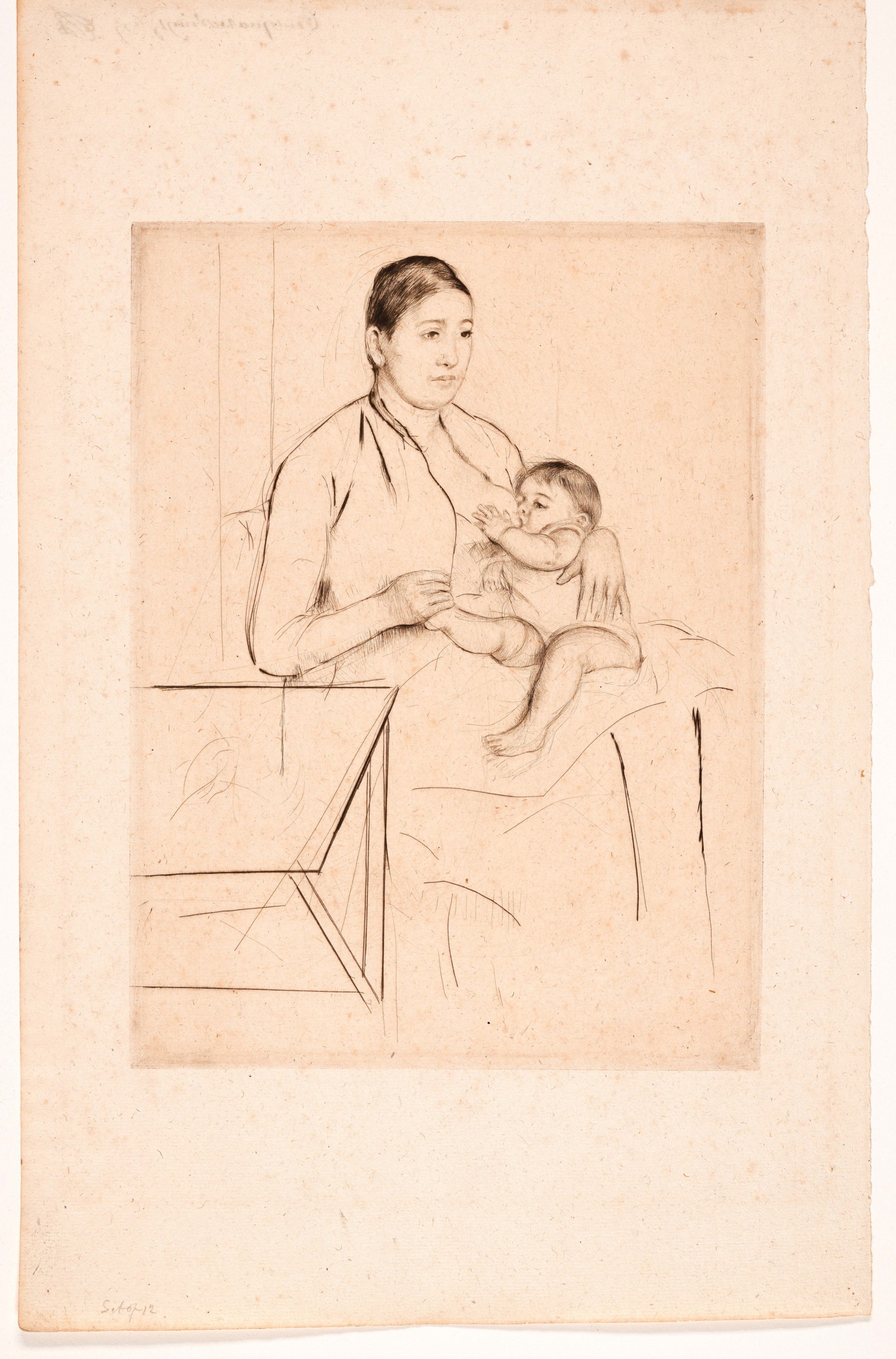

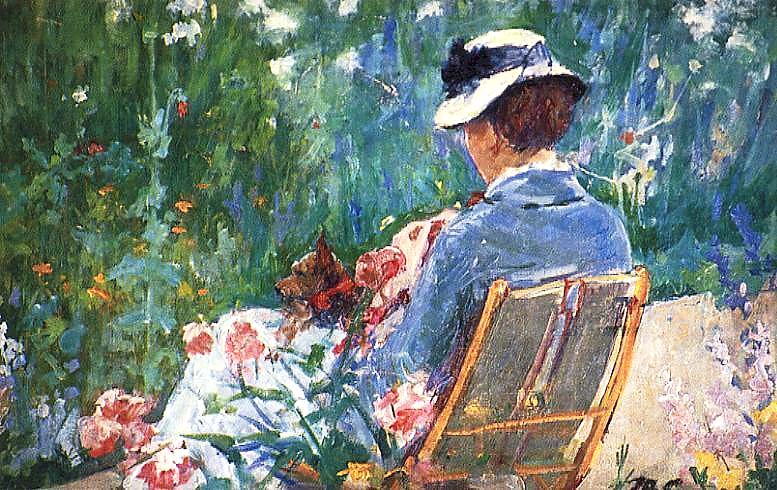

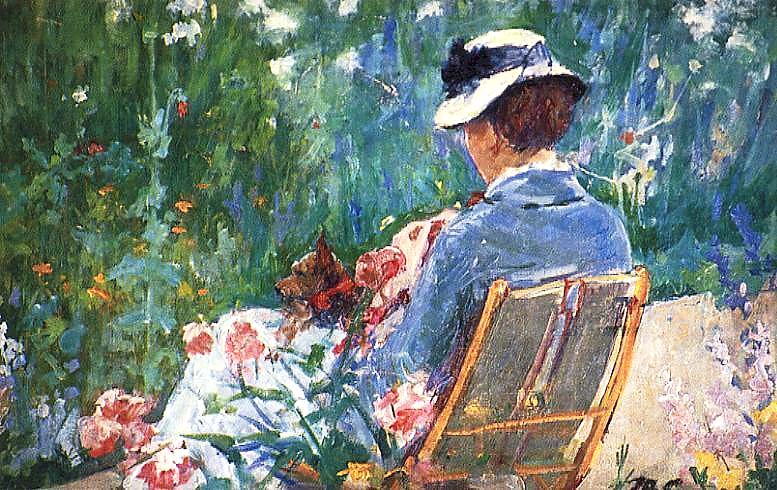

“Lydia Seated in the Garden with a Dog on Her Lap,” 1878-79, oil on canvas, 10¾ by 16 inches. Cathy Lasry, New York City.

By Kay Koeninger; all works of art by Mary Cassatt

PHILADELPHIA — Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) presents us with many anomalies. She was a major exception to her time and artistic milieu. She was a professional artist at a time when very few women (especially upper-class women) were able to do so. She was an American, but she spent most of her life in France and built her career there. Despite the challenges of gender and nationality, she was a full-fledged member of the Impressionists and showed in all their major exhibitions. She was extremely successful and exhibited regularly in both France and the United States and was also known as a shrewd appraiser of the art market and trusted advisor to important collectors. She confidently worked in different media and was especially known for her expertise in printmaking, a technical medium considered, at the time, to be more “masculine” than either painting or pastel, her other favored materials. In the words of Laurel Garber, The Park Family assistant curator of prints and drawings at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and one of the curators of the museum’s new exhibition, “Mary Cassatt at Work,” the artist “…lived a life of compelling contrasts.”

But her subject matter, viewed from a Twenty-First Century viewpoint, does not seem to fit our ideas of exceptionalism. Women at the opera and women sewing. Children, more children and even babies. Women and children. Domestic interiors. No landscapes. What is going on here? Why would such an artist confine herself to these subjects?

“Mary Cassatt at Work,” on view until September 8, addresses this question in detail. The answer is found in the word “work.” The exhibition is a joint venture with the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, where it will travel after its showing in Philadelphia, and is drawn from the collections of both museums as well as collections from across the United States. It is the first Cassatt show in Philadelphia since 1985 and will be the first ever solo exhibition of Cassatt in San Francisco. For Garber, research for the show was enriched by 84 Cassatt works and a collection of Cassatt family letters at the host institution.

“Mary Ellison Embroidering,” 1877, oil on canvas, 28¾ by 23 inches. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of the children of Jean Thompson Thayer, 1986, 1986-108-1.

In the foreword to the lengthy exhibition catalog, Cassatt is quoted from one of her letters, when she exclaims, “Oh the dignity of work…” The catalog notes that Cassatt mentioned work frequently in her correspondence and this focus, combined with her attention to the women of her time, holds a key to understanding her art. According to Garber, Cassatt’s art offers a unique perspective on “artistic labor, gendered work and the role of the artist.”

Cassatt rejected the Renaissance ideal of the artist as fueled only by inspiration and genius and distanced from physical labor. Instead, she saw herself as a worker, which can be seen as a modern idea. That classification for an artist, at least in the United States, did not become common until the 1930s. And even though Cassatt was from an upper-class background, her family disapproved of her art career and did not monetarily support any of the expenses related to her art making. Cassatt had to sell her art, as a worker, in order to support its production. She rebelled against the expectation that a “lady” artist must be an amateur. Her decision to become a professional artist against the wishes of her family and the expectations of her culture was a brave one.

Her upper-class background, even in the late Nineteenth Century, also dictated her social interactions. As an upper-class woman, Cassatt could not frequent Parisian bars and cafes, or freely stroll the streets, unlike the other male Impressionists. Approved public spaces for her included the opera, gardens and domestic interiors, all in the company of approved others, preferably family members. Women were the accepted subject unless men were from her family or their social circle. These environments dominate her art.

“Woman in a Loge,” 1879, oil on canvas, 32 by 23-5/16 inches. Philadelphia Museum of Art: Bequest of Charlotte Dorrance Wright, 1978, 1978-1-5.

These two aspects of Cassatt’s life — her need to see her art as work in order to secure her place in a masculine world and the restrictions dictated by her class and gender — provide a new lens for the viewer.

“Mary Cassatt at Work” demonstrates that an important element of Cassatt’s figural work was her emphasis on hands in action. Because she saw herself as a worker, she was sensitive to other women as workers as well. Strong hands, firmly gripping the child, are a hallmark of such paintings as “Maternal Caress” (1896). Cassatt’s depictions of “mothers and children” often did not include real mothers at all but paid models — women at work. The lack of sentimentality in these depictions are also tied to the modern idea that childcare is work. The physicality of childcare is also shown in Cassatt’s prints, such as her etching, “The Bath” (1890-91).

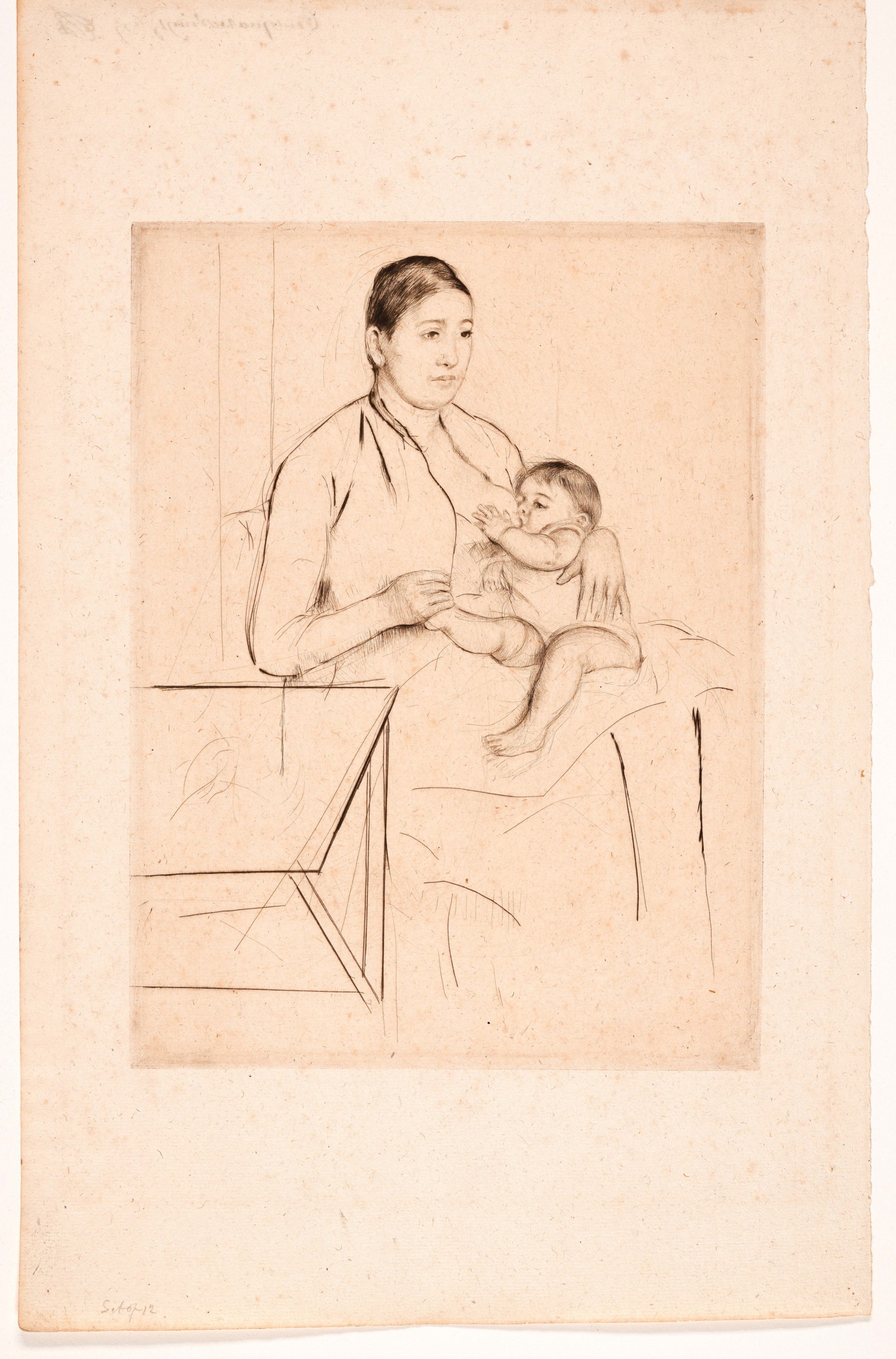

Cassatt’s depiction of childcare was so extensive that it also included breast feeding. Nursing was not a forbidden topic for other Impressionists, but they did not explore it with Cassatt’s frequency. One of her examples is “Nursing” (1890). In this etching, the artist uses a simple linear quality to depict the caregiver and the child. It is lacking sentimentality and without the romantic garden setting used by other Impressionists in their nursing depictions. The woman seems distant, or tired, pointing to the fact that she is probably a hired wet nurse. She is a worker.

“Nursing,” circa 1890, drypoint on laid paper, 9-7/8 by 7 inches. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of Mrs Horace Binney Hare, 1956.1956-113-9.

Another aspect of “women’s work” for Cassatt were the fiber handicrafts. She often shows women crocheting, embroidering or even weaving. In the painting “Lydia Seated in the Garden with a Dog in Her Lap” (1878-79), despite the fact that her back is turned to us, the focal point of Cassatt’s sister’s hands shows that she is crocheting. Even though she is in the relaxing atmosphere of a blooming garden, she is actively engaged in a complex task. A more traditional frontal view of a woman engaged in textile art is seen in “Mary Ellison Embroidering” (1877).

Though Cassatt’s art usually depicts women active in their own “sphere,” one of her paintings shows a woman engaged in what was considered a male occupation. In “Driving” (1881), the woman is shown driving a carriage, the coachman relegated to the back. She expertly holds the reins and the whip and is intensely focused on the job at hand. The child is holding on to the side of the carriage to suggest that they are traveling at a fairly fast clip.

Because of Cassatt’s highly productive and long career, she was able to explore technical innovations in media other than painting, and this aspect of her work is fully discussed in the exhibition catalog.

Her work in prints was central to her, and, in fact, she often would exhibit more prints than paintings during a year. Like most avant-garde artists of the time, Cassatt was drawn to the spontaneity of etching and its many variations. She was not afraid to use a variety of etching techniques in one print. “The Visitor” (1881), combines soft ground aquatint, dry point, and etching to produce a showcase of texture and tone. The print also expertly explores the tension between flat and three-dimensional space.

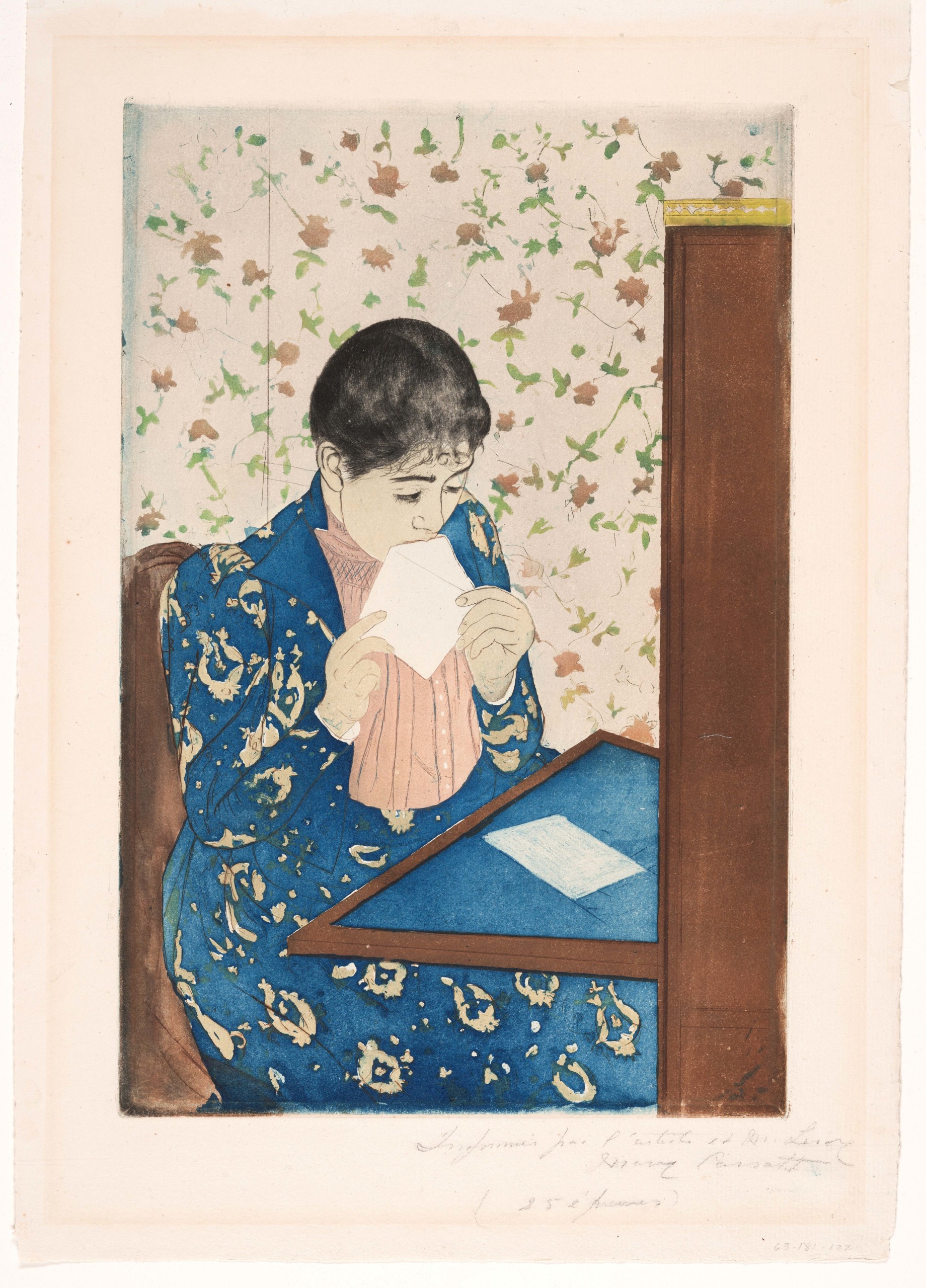

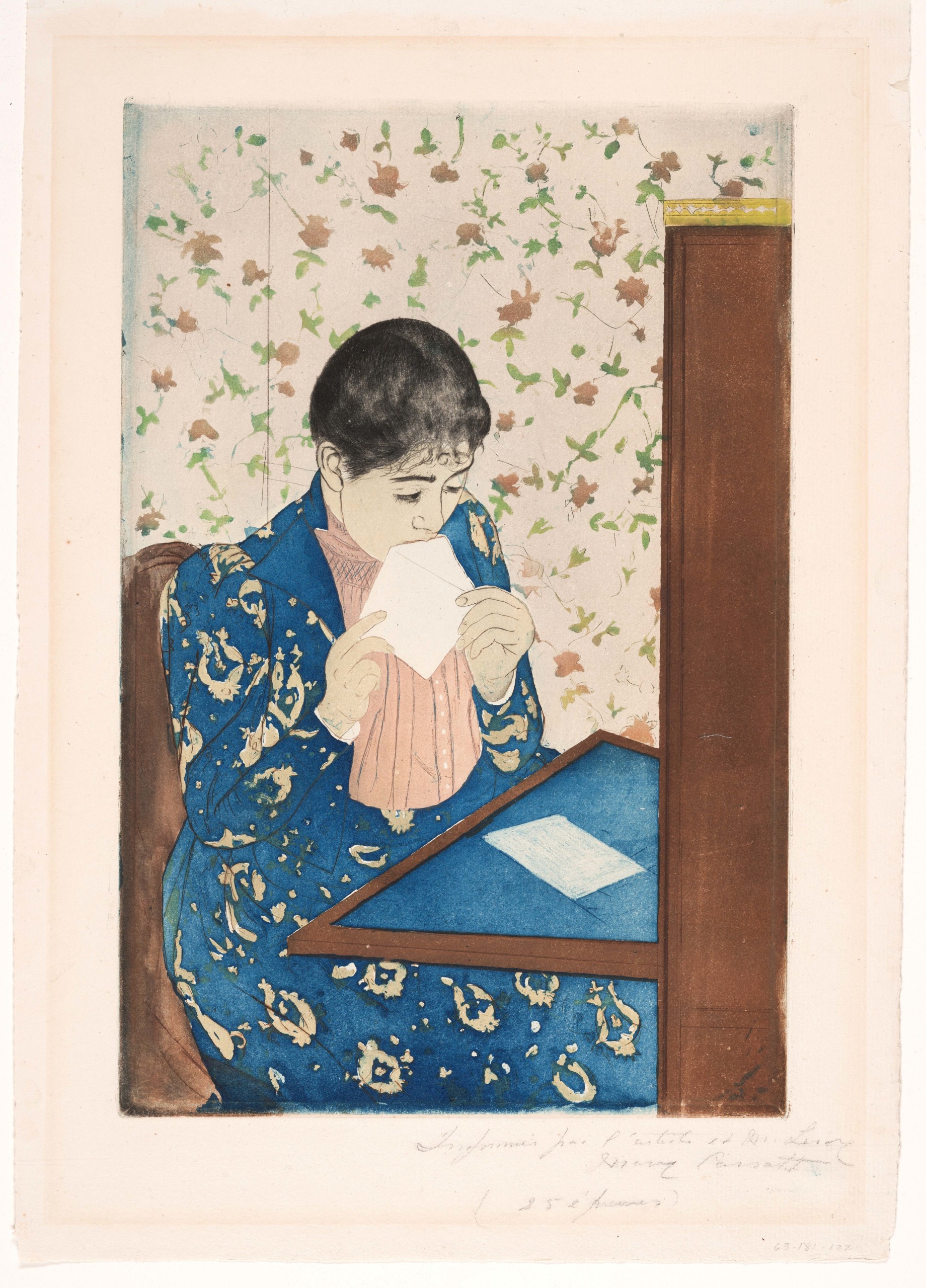

“The Letter,” 1890-91, color drypoint and aquatint on laid paper, 13-9/16 by 8-15/16 inches. Private collection. Courtesy of Waqas Wajahat, New York.

Cassatt, more than any other Impressionist except for Degas, incorporated elements of Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints into her printmaking oeuvre. In “The Letter” (1890-91), the composition includes Japanese-inspired pattern, cropping, strong diagonal lines and areas of flatness.

Cassatt’s print making interests also often informed her painting, although in more subtle ways. One of her most well-known works, “Little Girl in a Blue Armchair” (1877-78), is awash with pattern. For once a child is shown without a caregiver; the little girl, by herself, sprawls informally in a large armchair. The interplay of flat and dimensional space offers relief from the large areas of blue.

Another medium in which Cassatt distinguished herself was pastel. The catalog states how its quick application was perfect for capturing restless children. She used both textured paper and canvas coated with a variety of gritty primers. “In the Loge” (1879), captures Cassatt’s expertise in pastel and also shows her innovative use of gold paint. The large fan is an obvious nod to japonisme as well as divider between the public space of the theater and the privacy of the loge. In other pastels, such as “A Goodnight Hug” (1880), she expertly combined finished figures with a sketchy background.

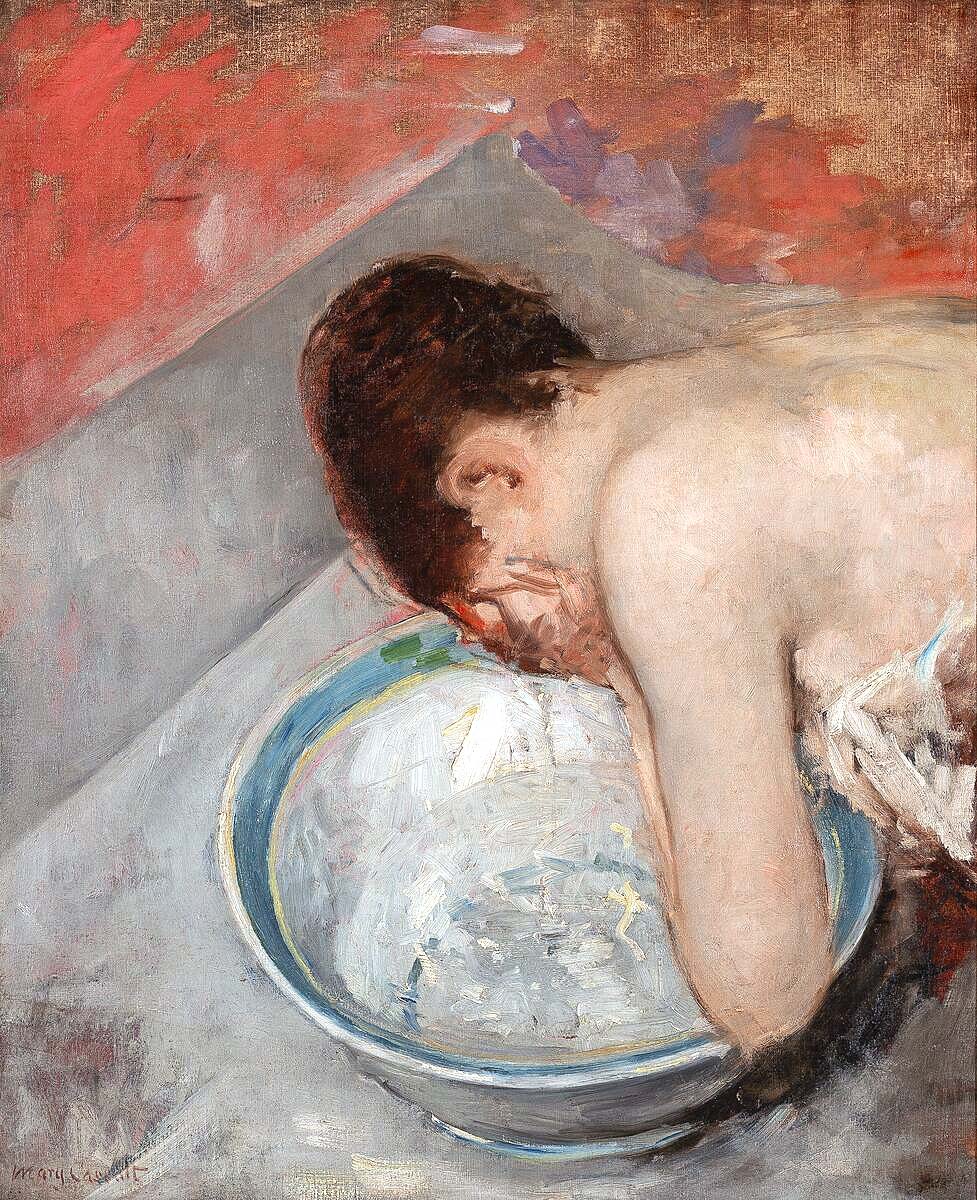

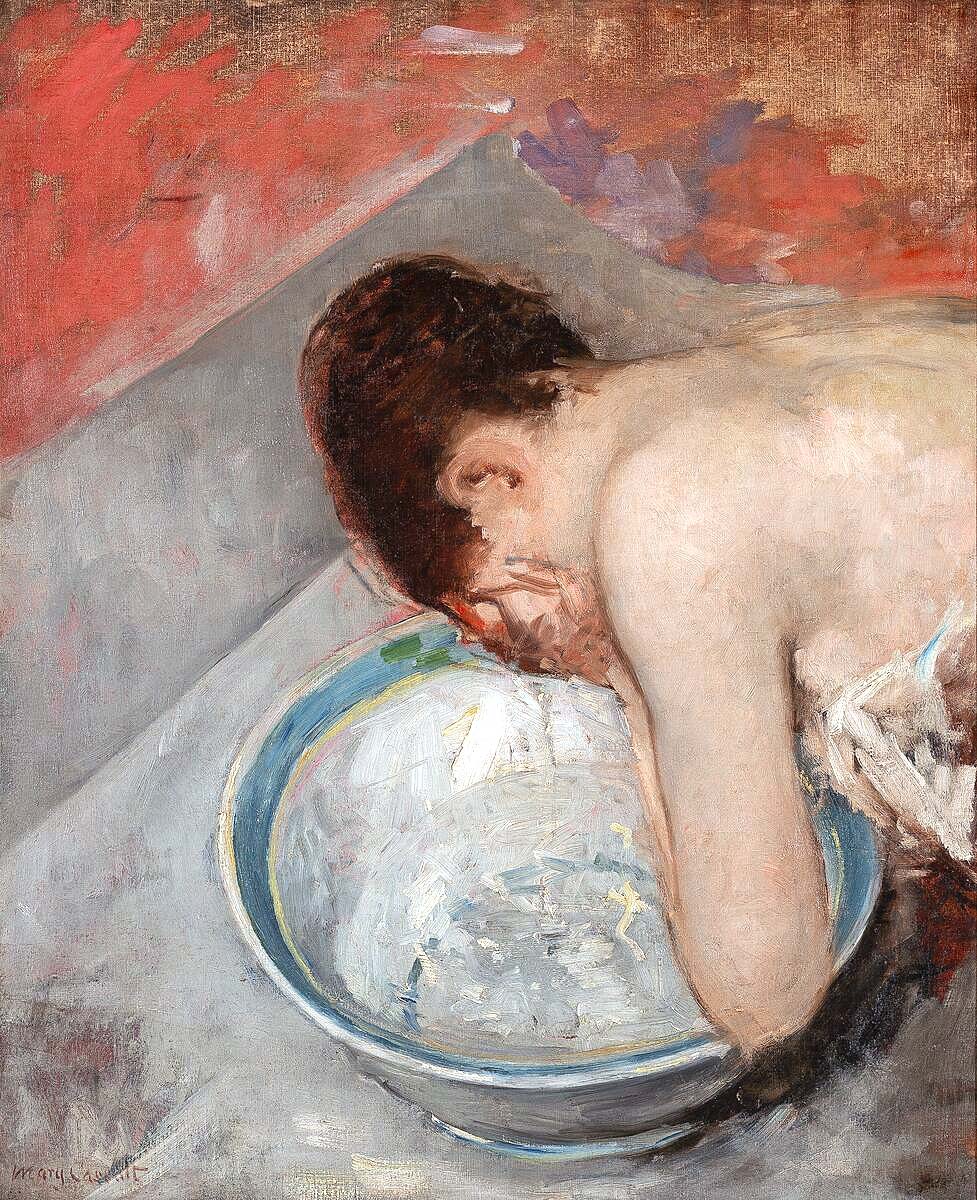

“Woman at Her Toilette,” circa 1891, oil on canvas, approximately 30 by 25 inches. Private Collection.

In contrast to the public space of the theater, Cassatt also explored private domestic activities. “Woman at Her Toilette” (circa 1891), shows how the artist applied a sketch aesthetic to paint, as well as cropping and the combination of both overhead and profile perspectives. The work is devoid of the awkward poses and voyeuristic atmosphere of similar subjects by Degas.

The catalog and exhibition also explore in detail other aspects of Cassatt’s artistic and personal life, such as her technical innovations in painting, prints and pastels, including her deep knowledge of materials, her comfort with combining different media, and her dedication to working and reworking her images. Her mural work for the Women’s Building at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago and her support of the women’s suffrage movement are also highlighted.

“Mary Cassatt at Work” offers the viewer a unique perspective on one of the most important American artists of the last half of the Nineteenth Century. Many of us have shortchanged her as we focused on her subjects of children, babies and women in stereotypical settings. She was up to something deeper — a more accurate, non-romanticized view of the world of women in her time. And as Cassatt saw herself as a worker, there was another crucial characteristic of the subjects she chose. They sold.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art is at 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway. For more information, 215-763-8100 or www.philamuseum.org.