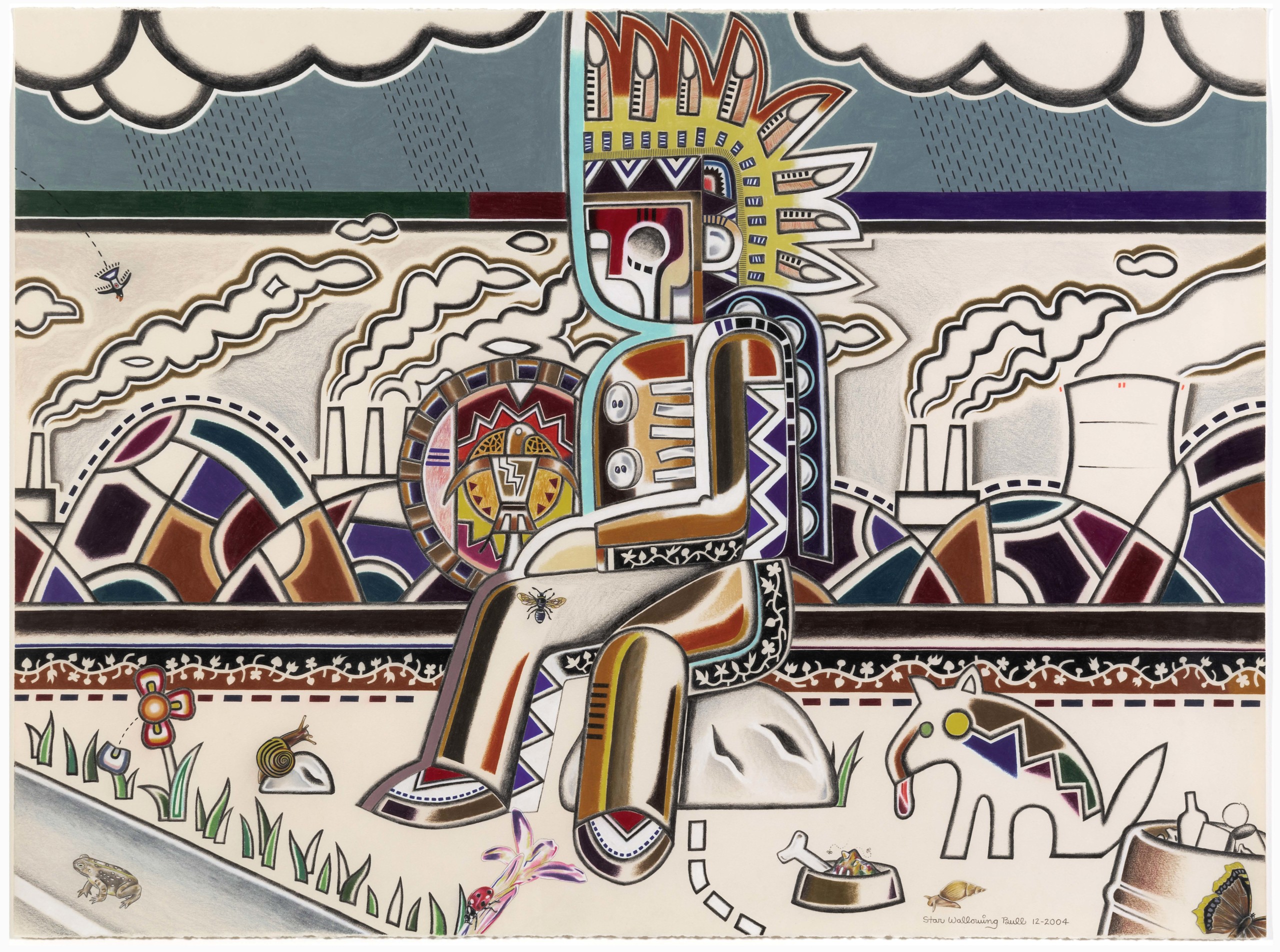

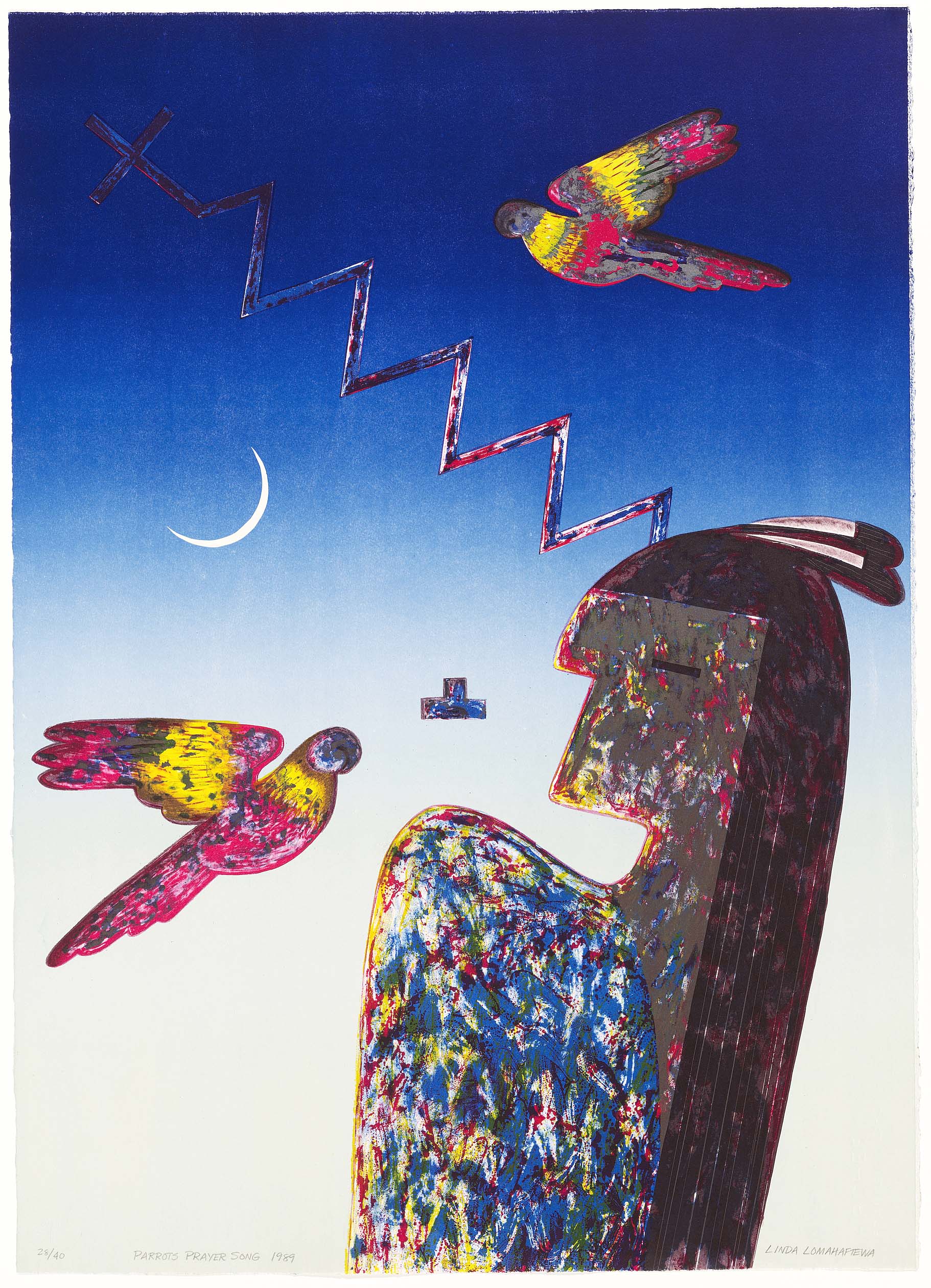

“Modern Day Indian” by Star WallowingBull, 2004, lithograph crayon and colored pencil on paper, 34¼ by 41½ inches framed. Collection Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Johnson County Community College, Overland Park, Kansas.

By Andrea Valluzzo

NEW BRITAIN, CONN. — Diversity is one of the most overused buzzwords in the last few years, but in the case of a groundbreaking and large-scale art exhibition, the word is apropos.

Traveling from the National Gallery of Art, where it was on view last fall until January 2024, “The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Art By Native Americans” has made its way to the New Britain Museum Of American Art (NBMAA), its only other venue, where it will be on view through September 15.

The exhibition is diverse across the board with more than 50 Native artists hailing from many tribal nations. The artists are as diverse as their subject matter, style and techniques. While works on paper dominate, there are also photographs, mixed media works, sculpture, video, fiber art, glass and ceramics on view. The installation is interactive and there are QR codes visitors can access to hear artists speaking about their own artworks, sharing additional insights.

The breadth of work on display in this exhibition has seldom been seen in one place together, let along been given their proper dues.

Native American and Indigenous art was once overlooked and treated as a footnote to American art history, which has largely been categorized by Western audiences using a Eurocentric framework. Historically, few museums have given exhibitions to Indigenous art except perhaps in the case of being a tangential one-off. At the National Gallery of Art, where this exhibition began, “Land Carries Our Ancestors” was the first showing of Indigenous art in three decades and the first to include contemporary works by living Native artists in seven decades.

It’s also a first for New Britain.

“Bang Bang” by Natalie Ball, 2019, elk hide, rabbit fur, oil stick, acrylic, charcoal, cotton and pine, 84 by 124 inches overall. Courtesy of the Rubell Museum.

Over time, Native American art has become integral in the canon of American art, thanks largely to efforts by artists such as Jaune Quick-to-See Smith. The artist, who hails from the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, served as the guest curator for this exhibition. In sharp contrast to many exhibitions that have presented Native American art solely through historic artifacts and artworks, Smith deliberately included contemporary works by living artists.

“Because the old myth that we are vanishing or are no longer here or that we are extinct has been so prevalent, I wanted to show as many living artists as the museum would allow,” Smith told Antiques and The Arts Weekly. “It also shows how gifted these artists are yet many people have never heard of them. So my mission was two-fold.”

“This is a wonderful introduction to many established and up-and-coming artists that are active in the art world. It opened the door for us to really start engaging more deeply in Native American art — both from the past and contemporary — and bringing our museum into a new era,” said Stephanie Mayer Heydt, director of Collections and Exhibitions at the NBMAA. “It’s a really important project and it’s the kind of show that we should be doing.”

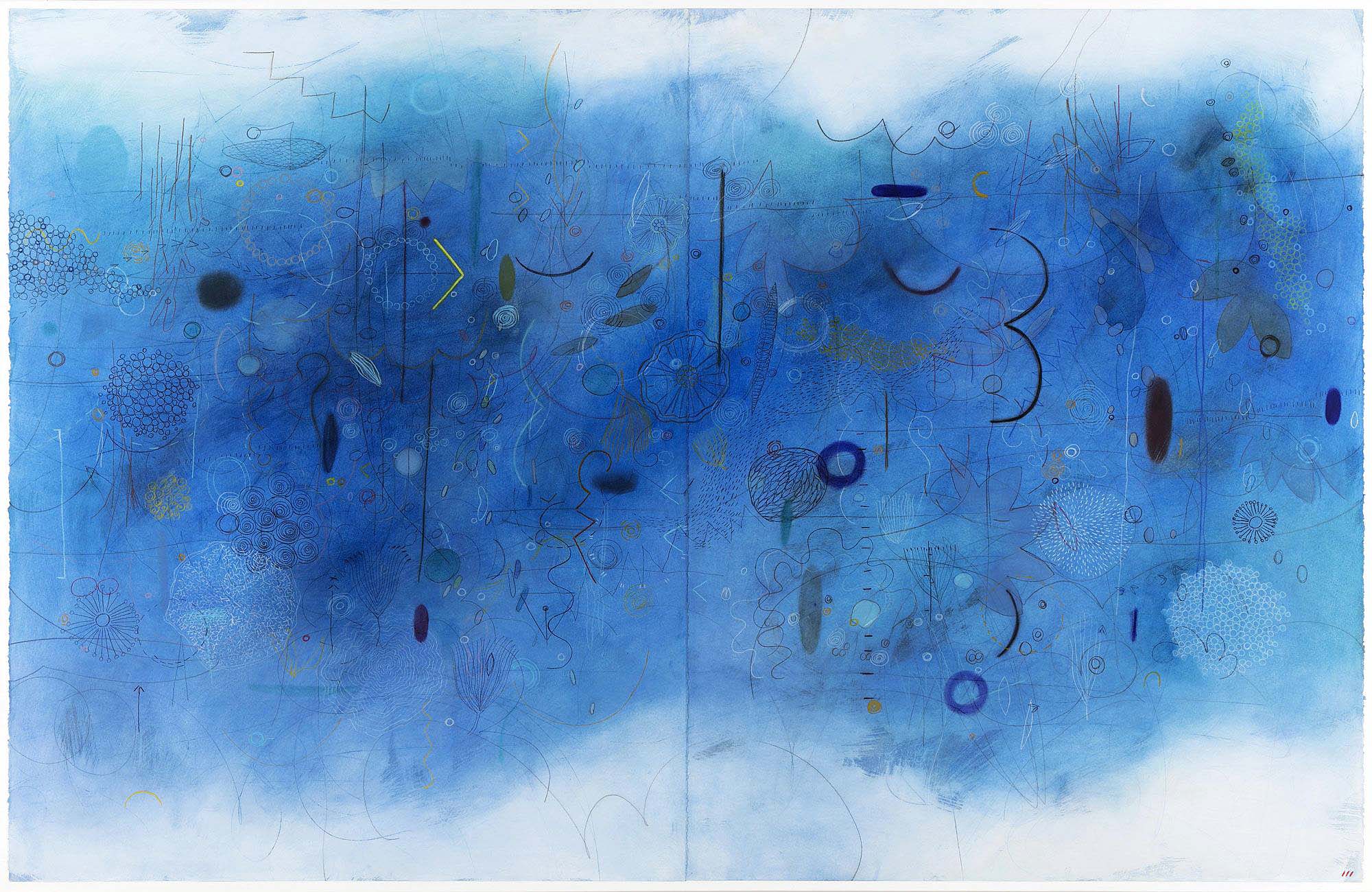

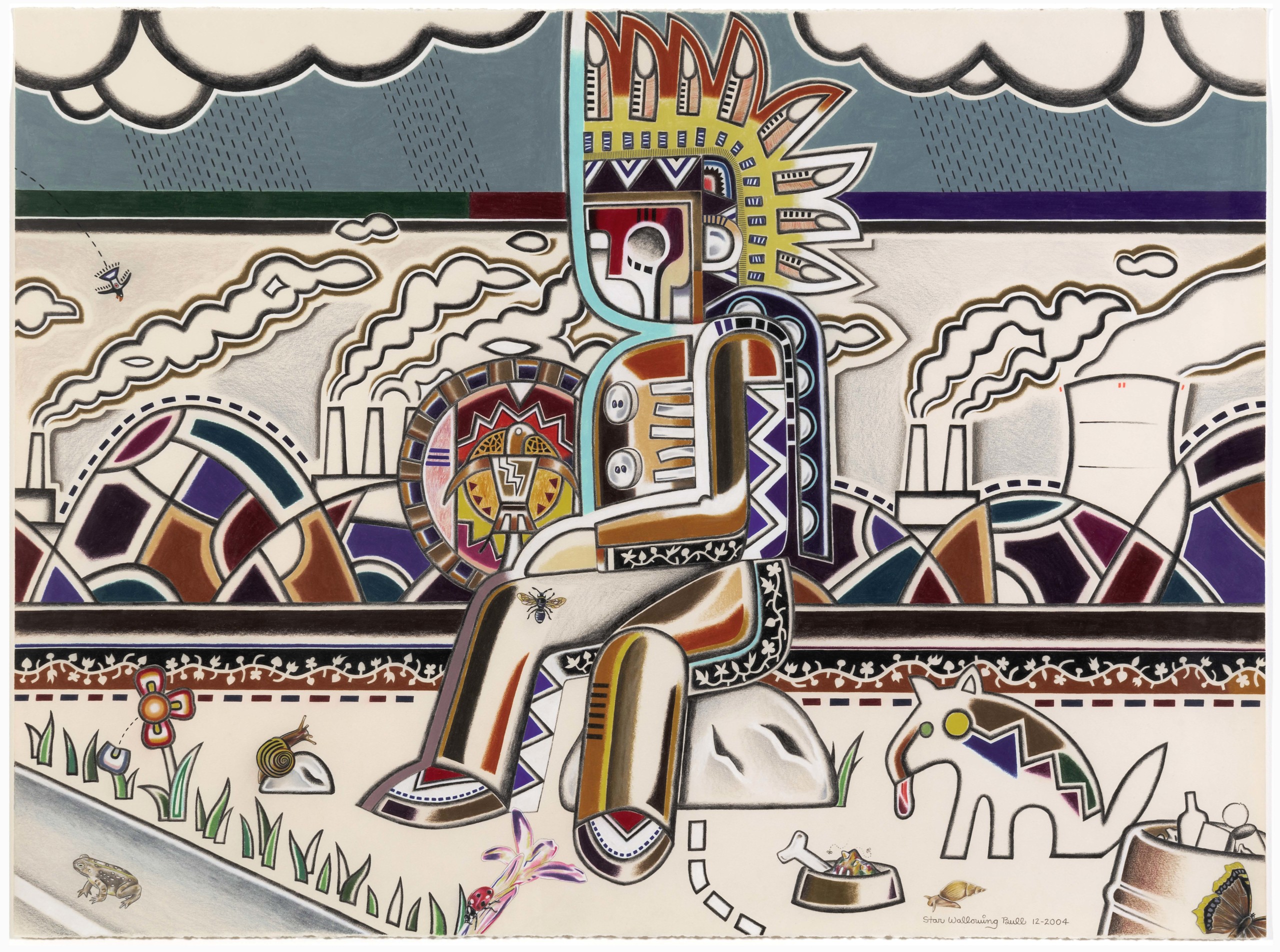

“Fog Bank” by Emmi Whitehorse, 2020, mixed media on paper on canvas, 51 by 78 inches overall. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, William A. Clark Fund.

A prolific artist who has curated many shows and elevated fellow Indigenous artists, Smith has assembled a multi-generational sampling of artists whose approaches to art-making are highly individual yet share common beliefs in caring for the land and holding it in esteem.

In Smith’s eyes, the artworks in the exhibition are not just beautiful objects to be viewed in a museum, they have a deeper meaning. “While they might not fit into the mainstream of Euro-American perceptions of landscape, they do represent our enduring connection to land,” she wrote in an essay appearing in the exhibition catalog. “We know that no matter where we go, the dust of the land carries our ancestors.”

Expounding on this point in her interview, Smith said, “They are beautiful objects period, but their beauty is layered in meaning and each has at least one story, if not more than one, that could have accompanied them. We didn’t have extra space in the catalog to do more writing nor more space on the labels in the exhibition.”

“The stories are deep and filled with cultural material and go way back in time. As Native artists, we can ascertain some of this when we see each other’s work but often the artist will tell us even more personal stories about the making of the work. But to answer your question about what a viewer might take away, of course, one thing I would hope is that they realize we are not vanishing and secondly, that Native artists make interesting and incredibly beautiful art.”

“Raven Steals the Sun” by Preston Singletary, 2017, blown and sand-carved glass 20¼ by 9 by 7 inches overall. Collection of Jerry Cowdrey.

With so many Indigenous artists and works of art to choose from, Smith had her work cut out for her in curating the exhibition. “One criteria was to show the different media the artists work in. A show of mainstream artists would not have beadwork or quillwork but to see beadwork on a grand pair of Italian Casadei boots, well, that makes a statement about the sophistication of Native artists. That was the sort of stunning surprise I was searching for when doing the research for the exhibition,” Smith explained.

Due to the fragile nature of some of the art, especially works on paper, only two institutions were chosen to host the show even though several expressed interest. The NBMAA had already begun working with Smith back in 2019 to acquire some of her works, so when the opportunity presented itself to mount this show, the museum jumped at the chance.

“She is an incredibly important artist who was bringing some new narratives into focus that aren’t necessarily featured in our gallery: narratives about American history that focus on the Indigenous experience and that is something we felt was important to address at the NBMAA,” said Lisa Hayes Williams, the museum’s curator and head of exhibitions. “I think as an American art museum, often our narratives have historically focused on traditionally Western ideas around landscape, especially those introduced by the Hudson River School artists of the Nineteenth Century, who depicted the American landscape as a beautiful Eden.”

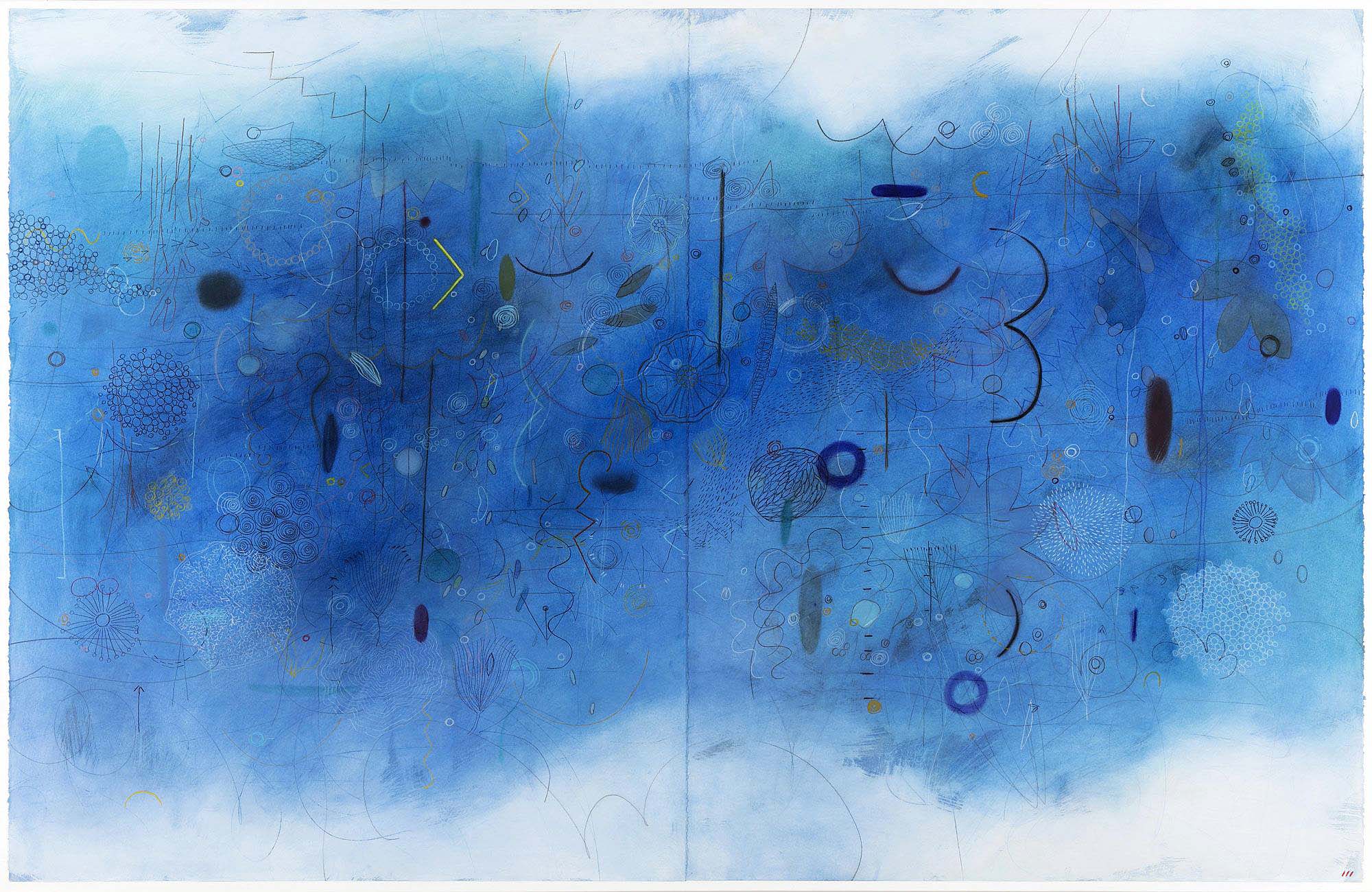

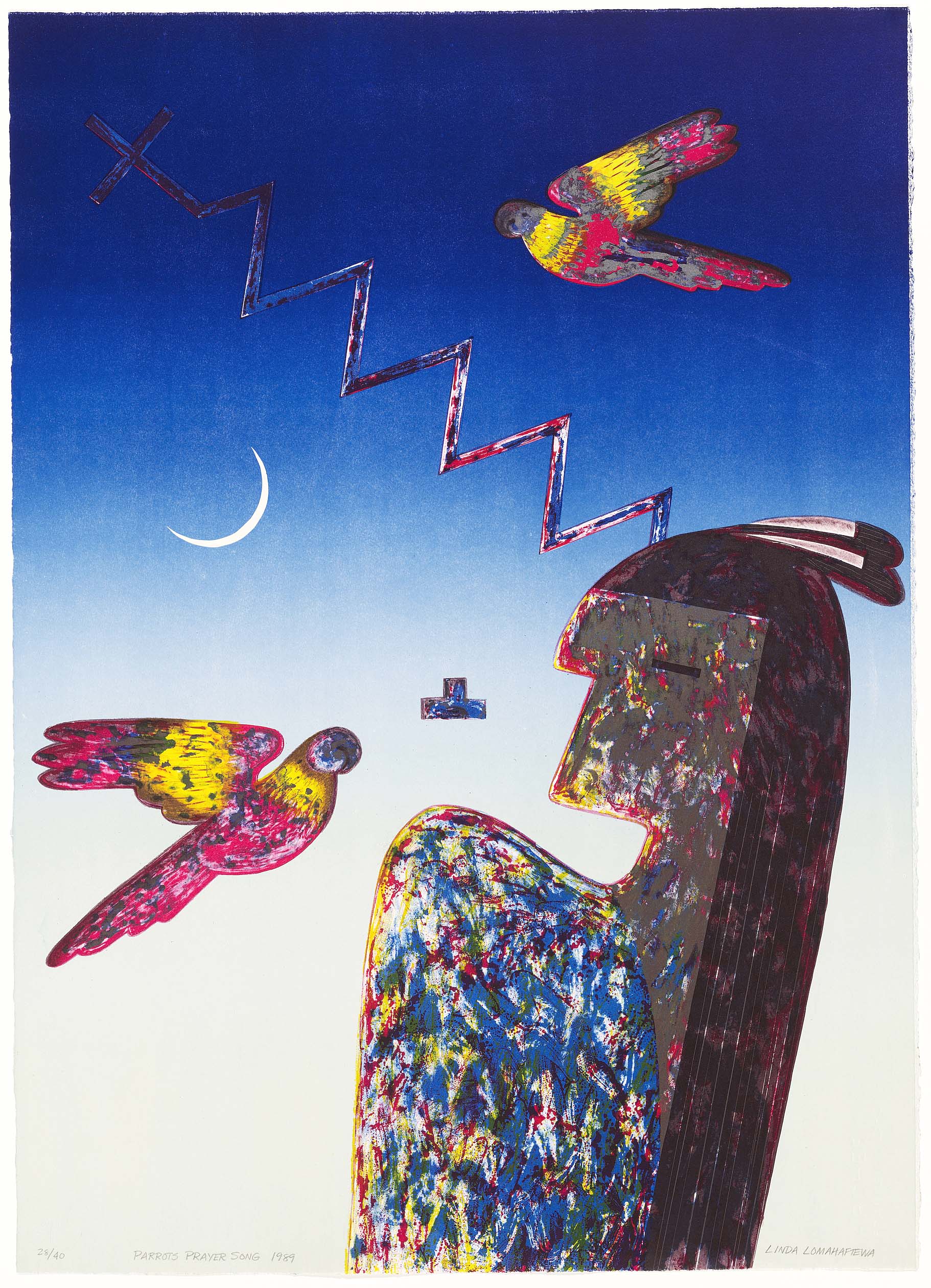

“Parrots Prayer Song” by Linda Lomahaftewa, 1989, color offset lithograph on wove paper, 30 by 22 inches. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Gift of Funds from the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation.

“In our museum, these are stories that have not necessarily been told, so it’s really wonderful to be able to now weave those stories against the backdrop of works that are here and the narratives that are sort of preexisting in the artwork we have displayed throughout our museum,” she added.

A throughline at the heart of the exhibition explores how Indigenous people differ in their view of the land from those who came from Europe and elsewhere to settle and colonize the United States. Indigenous people typically see themselves as stewards of the land instead of adopting notions of manifest destiny and “owning” the land. In the 1800s, settlers, aided by the government, moved West and took land from the Indigenous people who had lived on it for generations. Legislation like the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the Dawes Act of 1887 are two of the most well-known examples.

Instead of being organized chronologically, the exhibition is broken into three parts. The first, “Threads of Blue,” looks at how artists use blue in their artworks in relation to the landscape: the sky and waterways (lakes, rivers and oceans) in particular, as well as to demonstrate the interconnectedness of everything – from the land to its people. Works in this section range from Emmi Whitehorse’s mixed media on paper, “Fog Bank,” to Marie Watt’s “Antipodes,” using vintage Italian beads against felt to create a two-part work, spelling out “Skywalker” on top and “Skyscraper” on the bottom section. Illustrated on the cover of the hardcover exhibition catalog, Whitehorse’s painting, created with her own hands as well as brushes, is best described as “ethereal.” While not showing a landscape in the strictest sense of the word, it evinces her connection to place and is in keeping with her goals of showing natural harmony in the land, a philosophy well rooted in her Diné/Navajo heritage.

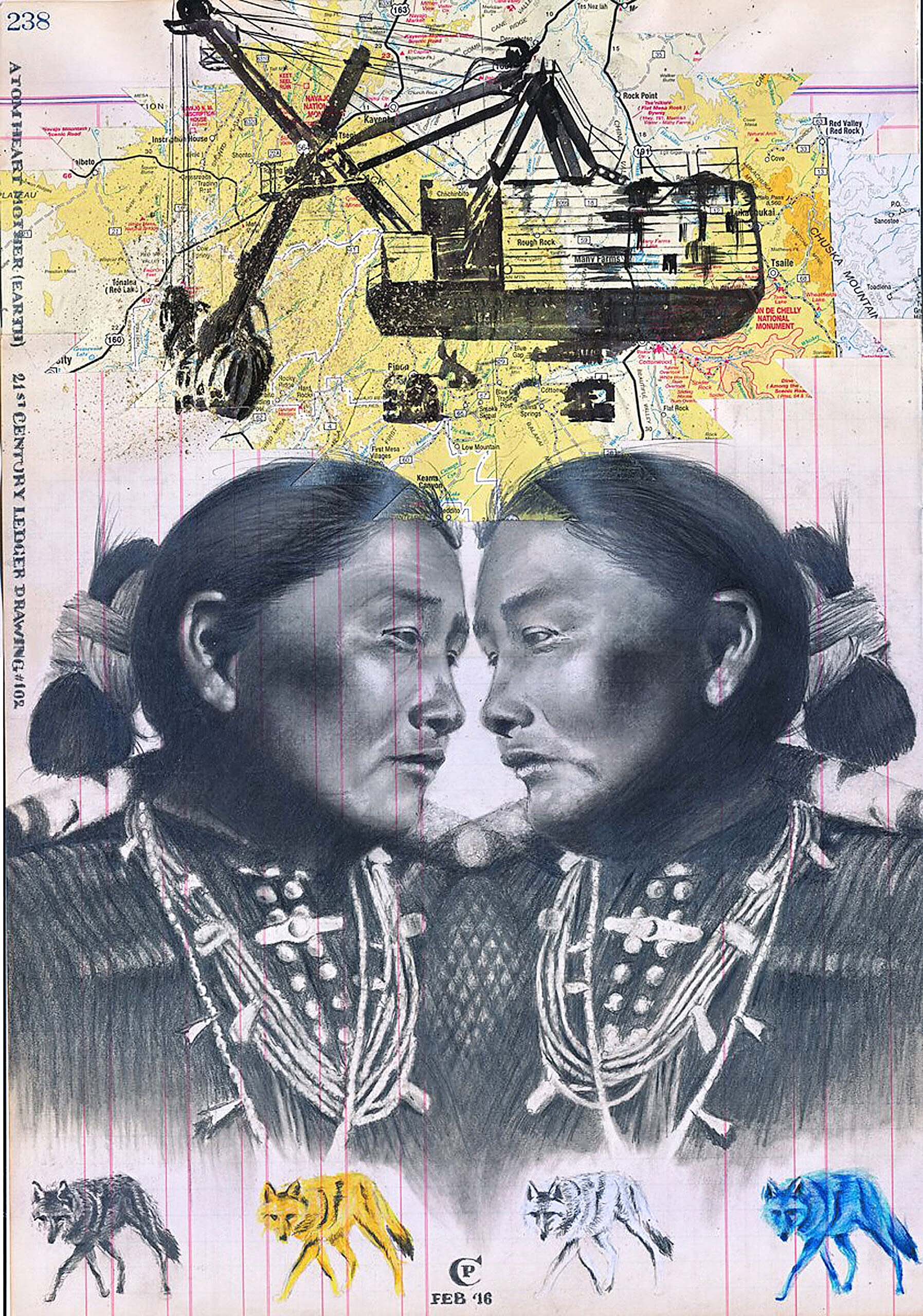

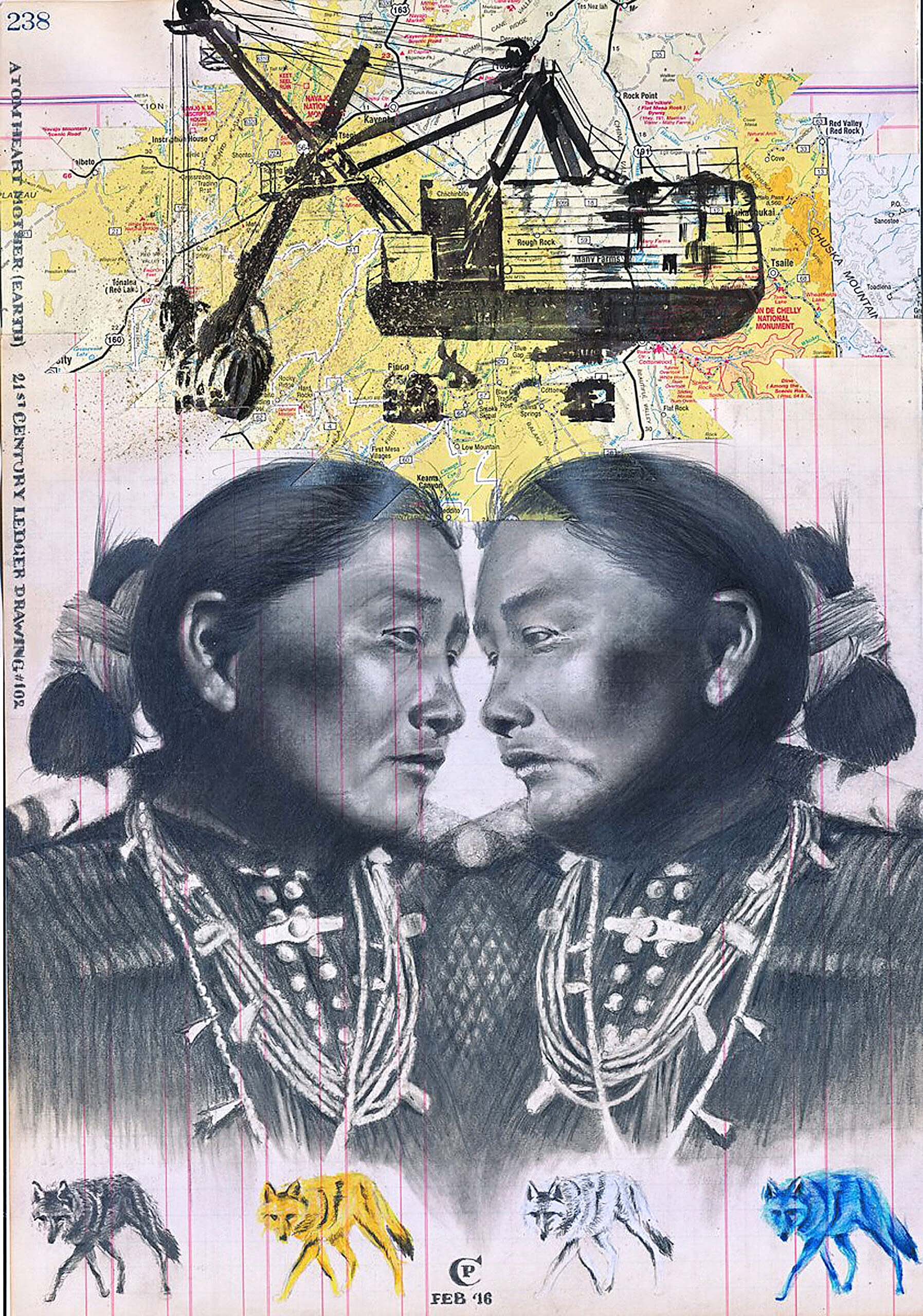

“Atom Heart Mother (Earth)” by Chris Pappan, 2016, mixed media on ledger paper, 24 by 19 inches framed. Courtesy of Travois.

The second section of the exhibition, “Checkerboard,” deals with the aftermath of how Native lands have been taken and corrupted. It’s a direct reference to the Dawes Act, which broke up ancestral lands, giving non-Native people much of the land. “It’s a very particular and unique way of approaching the installation,” Williams said, explaining that works on paper are hung corner to corner in two rows, resembling an actual checkerboard.

Among the works in “Checkerboard,” many of which address the hardships suffered by Indigenous people, is a lithograph crayon and colored pencil on paper by Star WallowingBull, an Ojibwe/Arapaho artist, which explores the dichotomy of nature and manmade machines in “Modern Day Indian.” In this precisely delineated geometric work, the artist was inspired by the pollution of his ancestral lands and the government’s policies of discarding nuclear waste onto Indigenous lands. In the exhibition catalog, WallowingBull calls these areas “radioactive reservations.”

In the “Always and Forever” section, the exhibition ends more hopefully. “It speaks to the resilience of Indigenous people and their effort to keep traditions alive and vibrant by addressing them in art…not forgetting the hardships that have been endured but to continue advocating and speaking for their Indigenous rights and protecting the land,” Williams said. “It’s a really optimistic note to end on. You have these really beautiful, hopeful paintings and I think this idea of healing comes through in a lot of the works.”

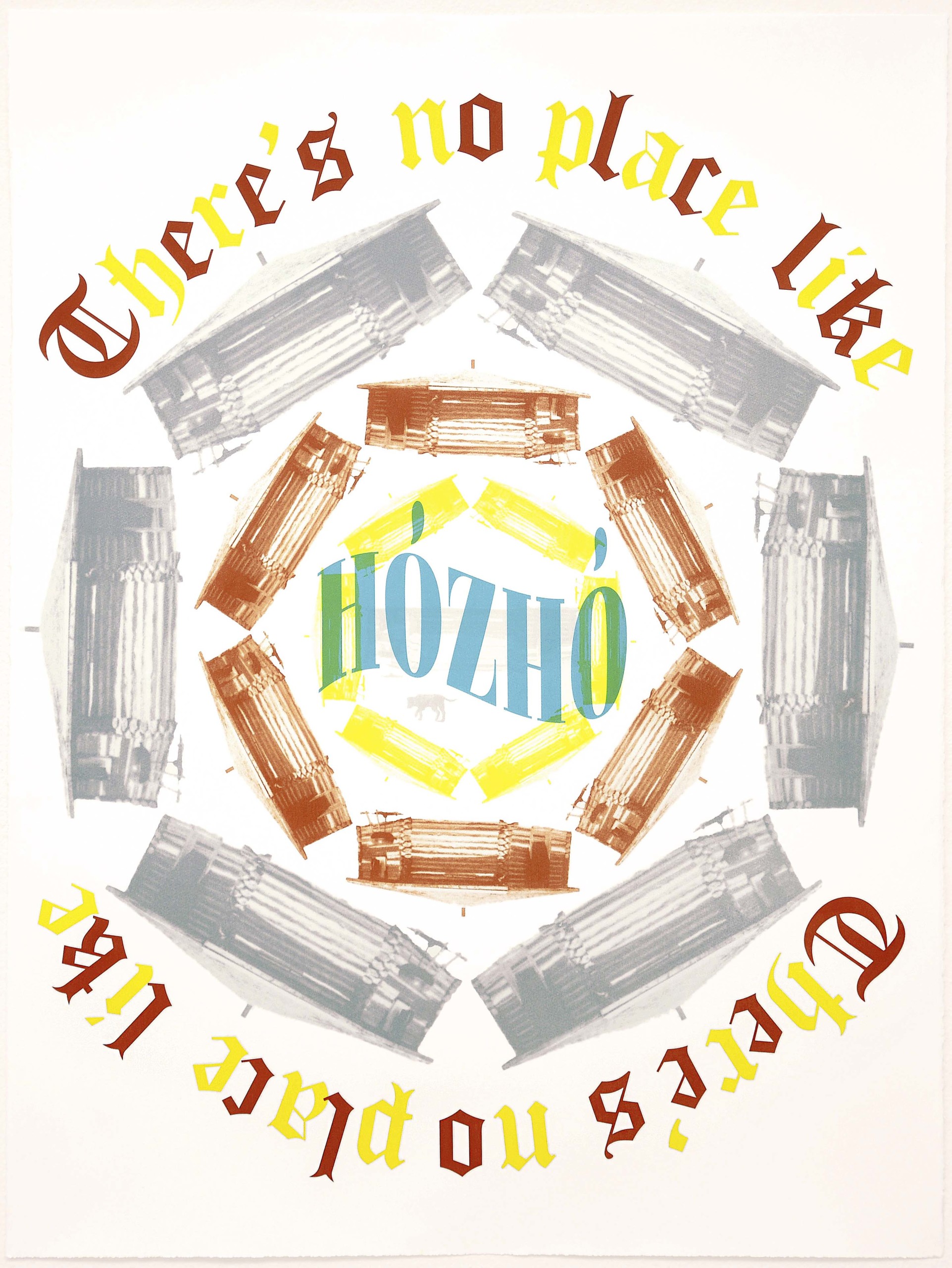

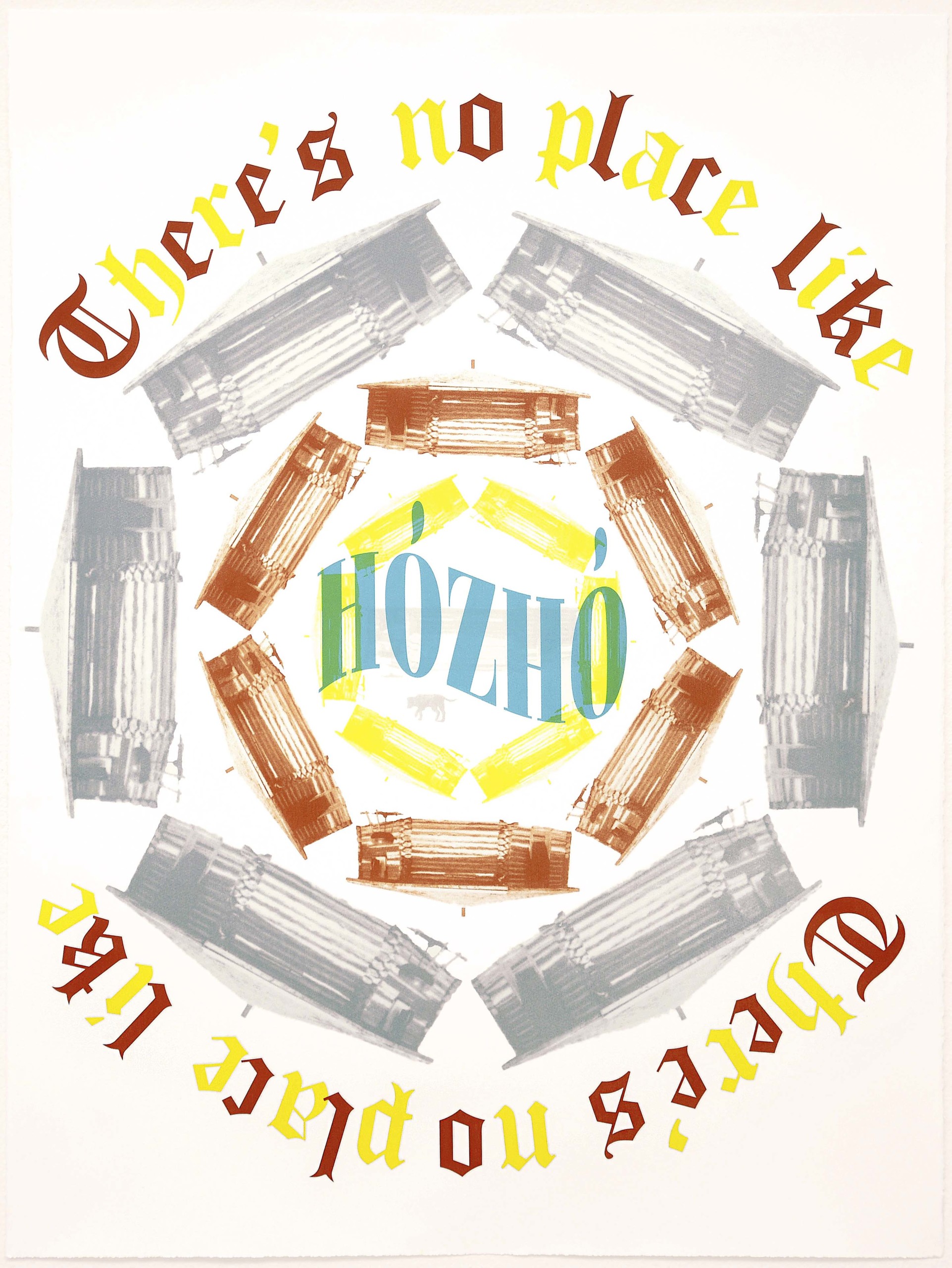

“No Place Like Hózhó” by Demian DinéYazhi ́, 2017, six-color lithograph, 46 by 37 inches framed. Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts.

Demian DinéYazhi’s six-color lithograph, “No Place Like Hózhó,” 2017, subverts the classic line of the movie The Wizard of Oz while showing a traditional Diné house tumbling through the air repeatedly. In this subtle artwork, the artist explores the ideas behind Hózhó’ — an important word in the Diné language. “‘No Place Like Hózhó’ refers to the spiritually and philosophically important Diné concept of goodness and balance,” she added. “The lithograph contemplates contemporary issues of detachment and longing that many Indigenous people confront while living under the betrayal of the settler-colonizer nation-state. It is also a hopeful and regenerative reminder of the power of Indigenous resilience and the importance of our ancestral lands.”

One artwork in this section is so powerful that it’s in the exhibition twice. Sort of. Steven Yazzie’s “Orchestrating a Blooming Desert,” a 2003 oil on canvas, is the final artwork in the exhibition, but a vinyl mural version of it is also the first artwork visitors see when entering. A figure, wearing modern but nondescript clothing, stands with his back to the viewer, holding a conductor’s baton in his right hand, as if conducting nature. In front of him is a colorful scene with lush grasses and flowers in full bloom that evince concepts of connections to the land and growth. “You have the sense of the environment and those living environments being in harmony and a sense of healing and abundance that I think was just a wonderful note to end on in the installation,” Williams said.

The New Britain Museum of American Art is at 56 Lexington Street. For information, 860-229-0527 or www.nbmaa.org.