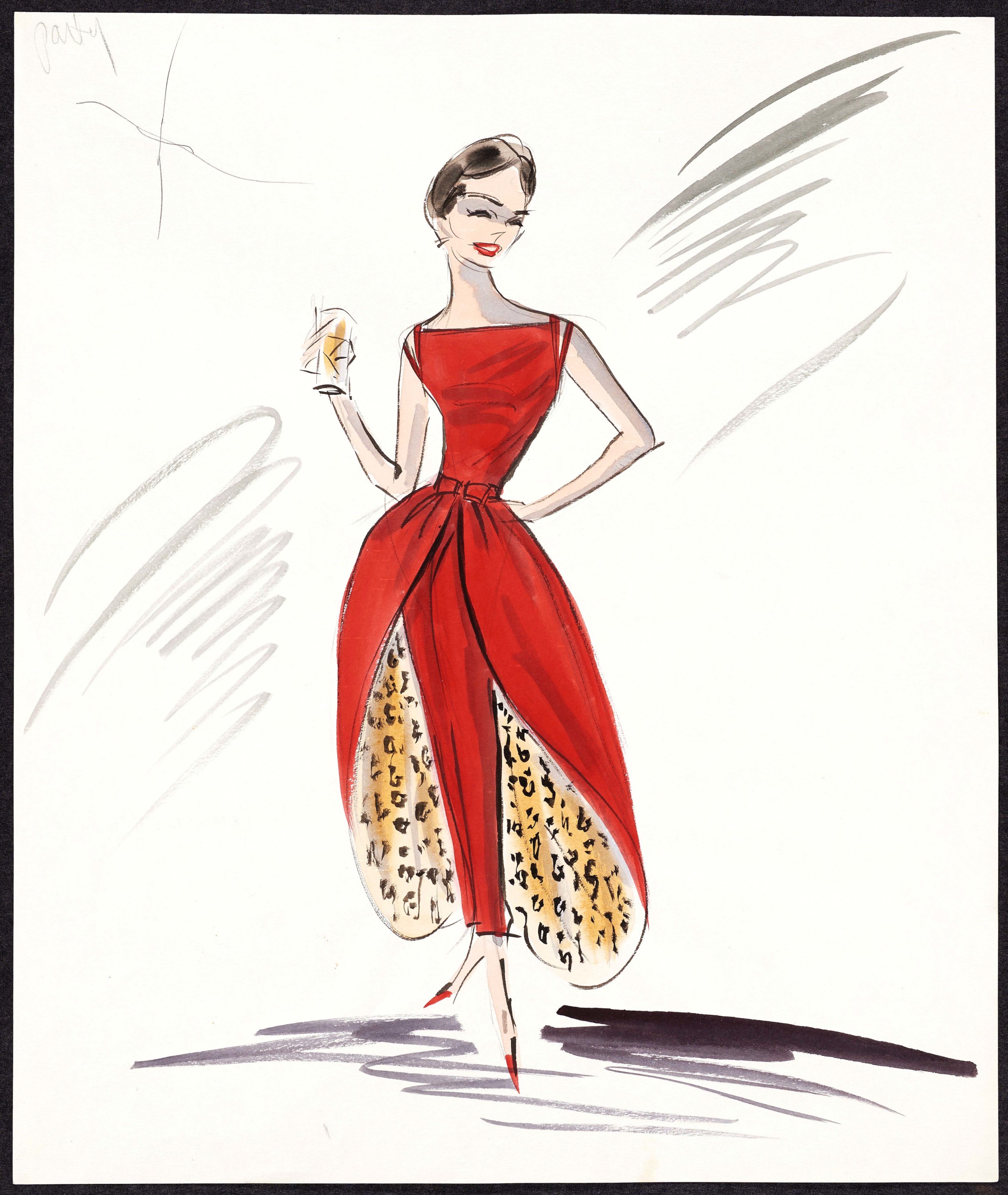

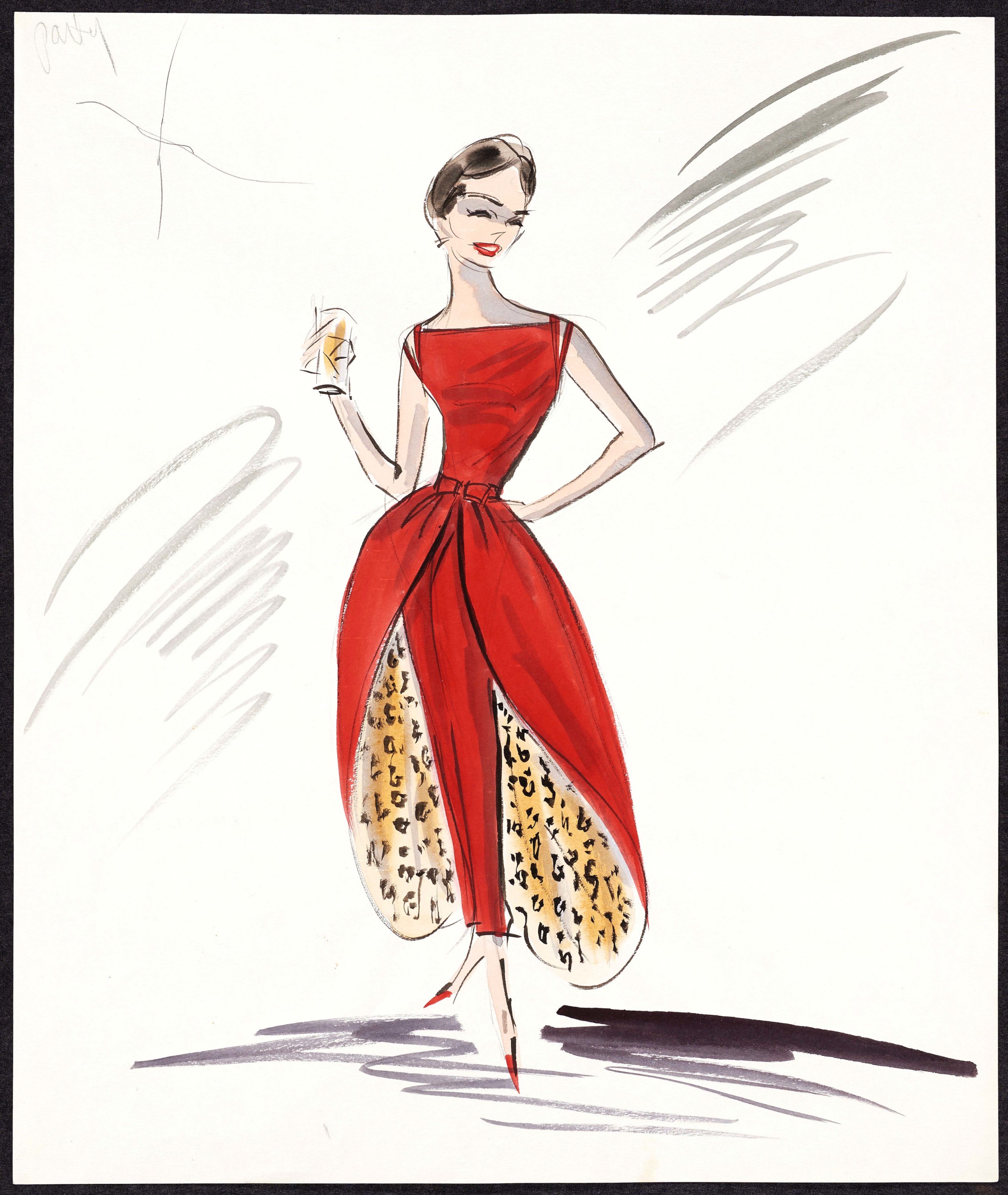

Costume design sketch of Audrey Hepburn as Holly Golightly in the film, Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

By Laura Layfer

OKLAHOMA CITY, OKLA. — Edith Head’s signature dark round glasses, short straight-cut bangs and tailored two-piece style suits, worn in an array of black, beige, white or gray, was the distinctive look that defined her own strong professional character. Her blue-tinted frames purportedly offered the proper shade to see her costume creations as they would appear on screen during the era of black and white films. Her personal choice of simple attire aided in distinguishing her role from that of the actors she dressed at both Paramount Pictures and Universal Studios. Now on view at the Oklahoma City Museum of Art (OKCMOA) and presented by the Ann Lacy Foundation, “Edith Head: Hollywood’s Costume Designer” features 70 costumes along with sketches, two screening sections and a few Oscar statues. After the Academy of Motion Pictures established the “Best Costume Design” category, Head was nominated 35 times and won eight times, a record for a woman in any category that stands to this day.

Preparation for the exhibition began three years ago, the idea of then OKCMOA curator Catherine Shotick, who was most recently named director of the Westerly Museum of American Impressionism and who had an interest that stemmed from fond childhood memories of watching old movies with her mother. Building on the OKCMOA’s long-standing focus on the art of film (the institution regularly hosts cinematic presentations and currently offers weekly movies in the museum’s Noble Theater with credits to Head), she and curatorial assistant Kristen Pignuolo worked closely to organize this exhibition. The bulk of the selections on loan came from two main sources: Paramount Pictures Archive led by Randall Thropp, and The Collection of Motion Picture Costume Design, run by costume historian and archivist Larry McQueen.

“Working with costumes was different from my past experience with other garments,” notes Pignuolo. “They can be incredibly elaborate on the exterior, couture-like in appearance, but the interior was often unfinished because they were really only meant to hold up for a few scenes and so were a lot less durable.” As she also points out, so many of these ensembles from the earlier part of the Twentieth Century were made when nobody was thinking about keepsakes and preservation for future display or archival purposes.

Edith Head, Alamy stock photo.

What happened behind-the-scenes (and “seams”) proved equally important to Head’s mastery of her skill in designing what the camera would see. Her own early life may have offered some element of preparing to play a part. She was born Edith Claire Posener in 1897, in Nevada, to two Jewish parents who soon separated. When her mother remarried, Head was presented as the daughter of her stepfather, and raised Catholic. The family moved to California where Head earned a Bachelor of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley, and a Master of Arts in Romance Languages from Stanford University. She became a Spanish and French teacher, and when the school needed an art instructor, she pursued what had only previously been a side passion and put herself forward as qualified for the post. Evening classes in drawing subsidized her lack of formal training and introduced her to first husband, Charles Head. Soon after, a classified ad for a sketch artist captured Head’s interest and she was hired by Paramount Pictures in 1923. She would later share that she had used sketches belonging to her classmates to land the job.

By 1938, Head had become the first woman to be named chief costume designer at a major production company and it was clear that she was an original in her craft. A decade later, in 1949, she received an Oscar, awarded for the burgundy silk velvet and taffeta two-piece tiered gown designed for Olivia de Havilland to wear as Catherine Sloper in The Heiress, for which de Havilland won for Best Actress. The costume, alongside the Oscar Head won for it, are on view to open the exhibition; it is one of three included in the galleries.

Costume worn by Olivia de Havilland as Catherine Sloper in the Paramount Pictures production of The Heiress, 1949. Designed by Edith Head. Collection of Motion Picture Costume Design: Larry McQueen.

“Apart from her ability to design for the script and the character, she had a skill in helping actors and actresses mold into their personas,” notes Pignuolo. Head’s approach was a blend of studious and sensitive, a manner perhaps taken from her time as an educator working with students. Throughout the entire third floor of the exhibition, a roster of Hollywood’s Golden Age bold-faced names are represented by way of their costumes and leading roles. Formal wear such as the black evening gown that belonged to Barbara Stanwyck in The Lady Eve (1941) is accompanied by a still image of the actress in an iconic scene. She apparently said that she never felt more beautiful than when dressed by Head for that character. Similarly, Veronica Lake, often referred to as a bombshell of the 1940s, was quite small in stature, standing at just under 5 feet. Her sultry wavy hair might have weighed her down without Head’s knowledge of how to play with patterns and shapes to elongate a feminine figure. For example, a white suit worn by Lake in Duffy’s Tavern (1945) is adorned on the jacket with a vertical embroidery intended to raise the audiences’ eyes up from the accentuated cinched peplum waist (Head apparently said that Lake had the tiniest waist in Hollywood) and solid straight skirt that had a dual purpose as it also hid extra high heels. Prior to each film, there were sketches made in order to achieve the proper silhouette and its approval for a costume; many of those on view include fabric swatches of the materials incorporated.

Installation photo of the blue suit designed by Edith Head for Kim Novak in Vertigo. OKCMOA photo.

The vignettes in the galleries explore Head’s progression alongside that of the booming film industry. In the 1950s, it became less about what she could conceal and more about how to reveal. The movement towards musicals, comedies, action and of color in film required a change to bold hues stitched with elements of sequins and beads of greater sheen for more texture to appear with movement. Sophistication, no matter the decade, was a mainstay for Head. The elegant ensembles worn by Audrey Hepburn in Sabrina and Funny Face partnered Head with Hubert de Givenchy. When Head won an Oscar for her work in Sabrina, neither she nor the Academy acknowledged the French fashion designer. It was an omission that was rectified with the production of Funny Face. Director Alfred Hitchcock found kinship, and acquiesced, in Head’s need for control. The duo worked on several pictures including Rear Window with Grace Kelly; her silk and organza dress is shown, as is the navy piece worn by Kim Novak in the famous Golden Gate Bridge water scene in Vertigo. Another part of the exhibition offers a beach-like decor to complement wardrobes along that theme, including those Head designed for Elvis Presley films.

In 1934, the Hays Code was enforced and brought to studio practices new regulations during this time of censoring content and costuming. Following it in the exhibition is a more somber section that explores the impact of World War II, where fabric rationing restrained the use of material as well as the overall mood in nearly every film genre. One variation is demonstrated with a lady’s suit finished in a simple black single layer is contrasted with a similar yet post-WWII example, done in a double-lined stitching with velvet accents at the cuffs and collar. In the 60s, rising television programs and a growing international film culture brought competition and, as a result, a return to excess in myriad ways. This is displayed in many of the elaborate silhouettes and sheer scale of Head’s creative output for epic films, namely those produced and directed by Cecil B. DeMille, such as The Ten Commandments and Samson and Delilah. “I think one of the aspects that surprised me most was just the tremendous volume required of Head and that she and her staff were frequently designing for thousands of extras,” says Pignuolo.

Installation view of the section of the exhibition dedicated to 1940s designs influenced by WWII rationing and the Hays Code. OKCMOA photo.

It was at the invitation of Hitchcock that Head eventually left Paramount Pictures after 43 years, joining Universal Pictures in 1967, where she worked for the duration of her career. Of her vocation, Head had been quoted: “Then a designer was as important as a star… their magic was part of selling a picture.”

Head was good at marketing herself. She wrote for magazines and newspapers, appeared on television as a recurring guest on Art Linkletter’s show House Party, formed a licensing agreement with Vogue Patterns, and even published two books: The Dress Doctor and How To Dress for Success. One unusual piece in the exhibition is a bright yellow and red evening set from her personal collection. It is a small peek at how different her private side at home was from the woman known for an attire of subdued classics at work. In 1940, after divorcing Charles Head, she married Wiard Ihnen, an art director she had met at Paramount. The union that Head maintained with Hollywood, however, was her most public and prolific. She was known to refer to her eight Oscars as “my children.”

Edith Head. Alamy stock photo.

Head would have fit right in with today’s world of celebrity stylists and social media. She designed a wedding dress for actress Natalie Wood when she became a bride, and Bette Davis apparently signed on to All About Eve with the firm understanding that Head would be her chosen costume designer. Her association and friendships with Hollywood glitterati was sustained in her ability to stay current, never swayed by trends, and above all else her incredible loyalty to stories and subjects. That is perhaps the appreciation visitors will take away most in learning about Head’s fame. As actress and comedian Lucille Ball was said to have remarked, “Edith doesn’t tell.” Rather, one might think, she designed to show the best of who she and others wanted to be, and even if it was only fantasy, it was her reality.

“Edith Head: Hollywood’s Costume Designer” will be on view at the OKCMOA, its sole venue, through September 29.

The Oklahoma City Museum of Art is at 415 Couch Drive. For information, www.okcmoa.com or 405-236-3100.