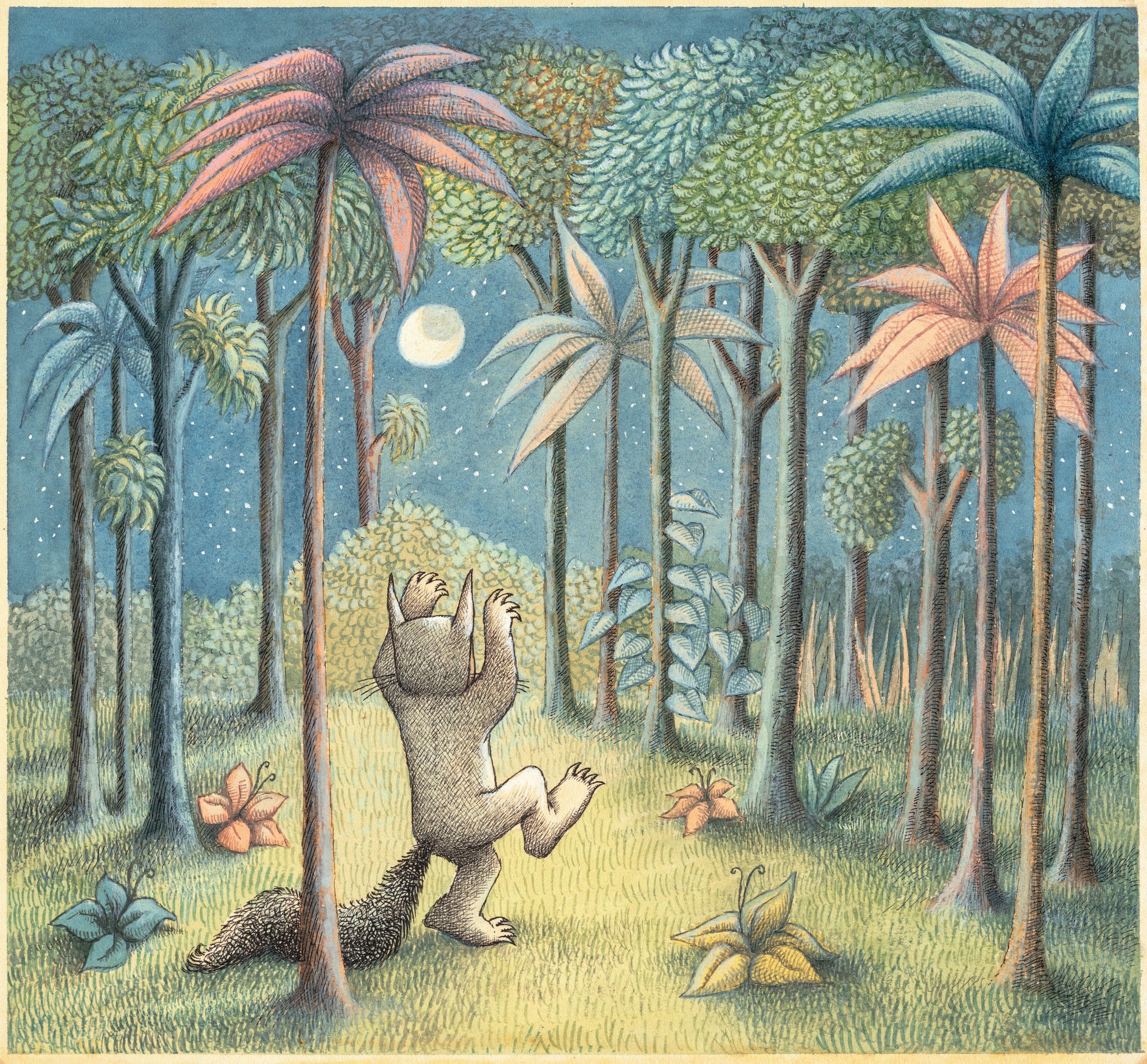

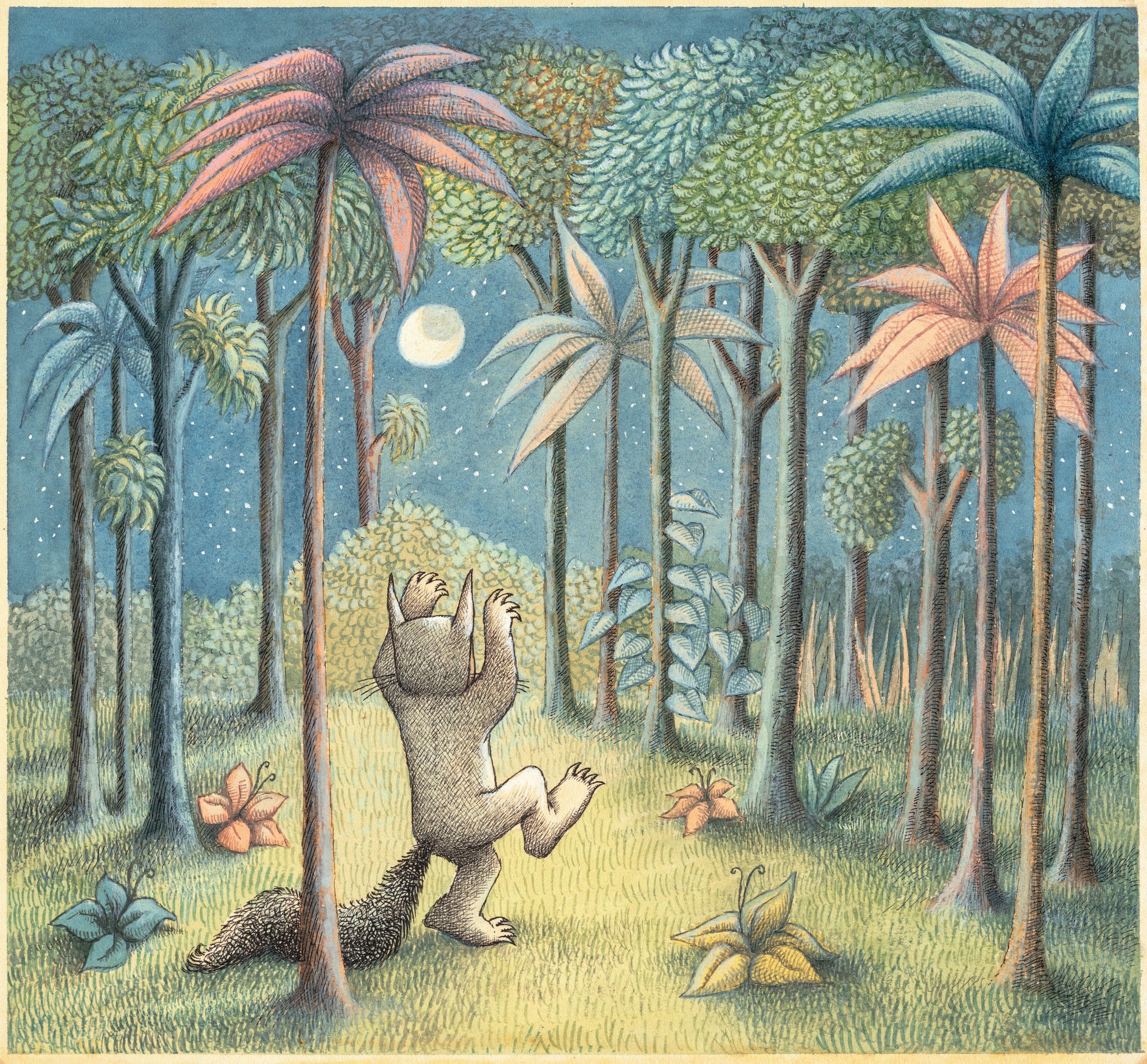

“Where the Wild Things Are” by Maurice Sendak, 1963, watercolor, ink, and graphite on paper, 9¾ by 11 inches. ©The Maurice Sendak Foundation.

By James D. Balestrieri

DENVER, COLO. — “Let the wild rumpus start!” or “begin,” depending on which version of Where the Wild Things Are you’ve read. “Start” or “begin,” it matters not at all to Max, the unruly lad banished to his room without his supper and left alone there with his very vivid imagination in Maurice Sendak’s classic children’s story. “Having little kids is great,” a colleague once said to me, “because you can watch all the old Disney movies and read all the really great kids’ books without feeling weird.” My kids are grown-up now, but I still watch their movies and read their old books, the ones that have survived the rightsizing and downsizing, the great ones — like Where the Wild Things Are — that will await grandchildren, should there ever be any, or find their way into new hands down the road. I tell myself that it’s research for essays such as the one you are reading right now. “Wild Things: The Art of Maurice Sendak,” on view at the Denver Art Museum until February 17, lets us pay a visit to and indulge our inner kid without any need to excuse our enthusiasm, but with our eyes open to Sendak’s honest vision of childhood as one part exuberance, one part terror.

Maurice Sendak was born in Brooklyn in 1928. His parents were Polish Jewish immigrants. Largely self-taught, he embarked on his career as an illustrator in 1947. As Christoph Heinrich, the Frederick and Jan Mayer director of the Denver Art Museum and co-curator of this exhibition, says, “Sendak’s identity and experiences as a first-generation American, combined with the legacy and heritage of his Polish Jewish family, especially through WWII and the Holocaust, make his personal perspective and artistic insight immensely valuable, powerful and timeless.”

Portrait of Maurice Sendak by Annie Liebovitz, 2011. Annie Leibovitz / Trunk Archive.

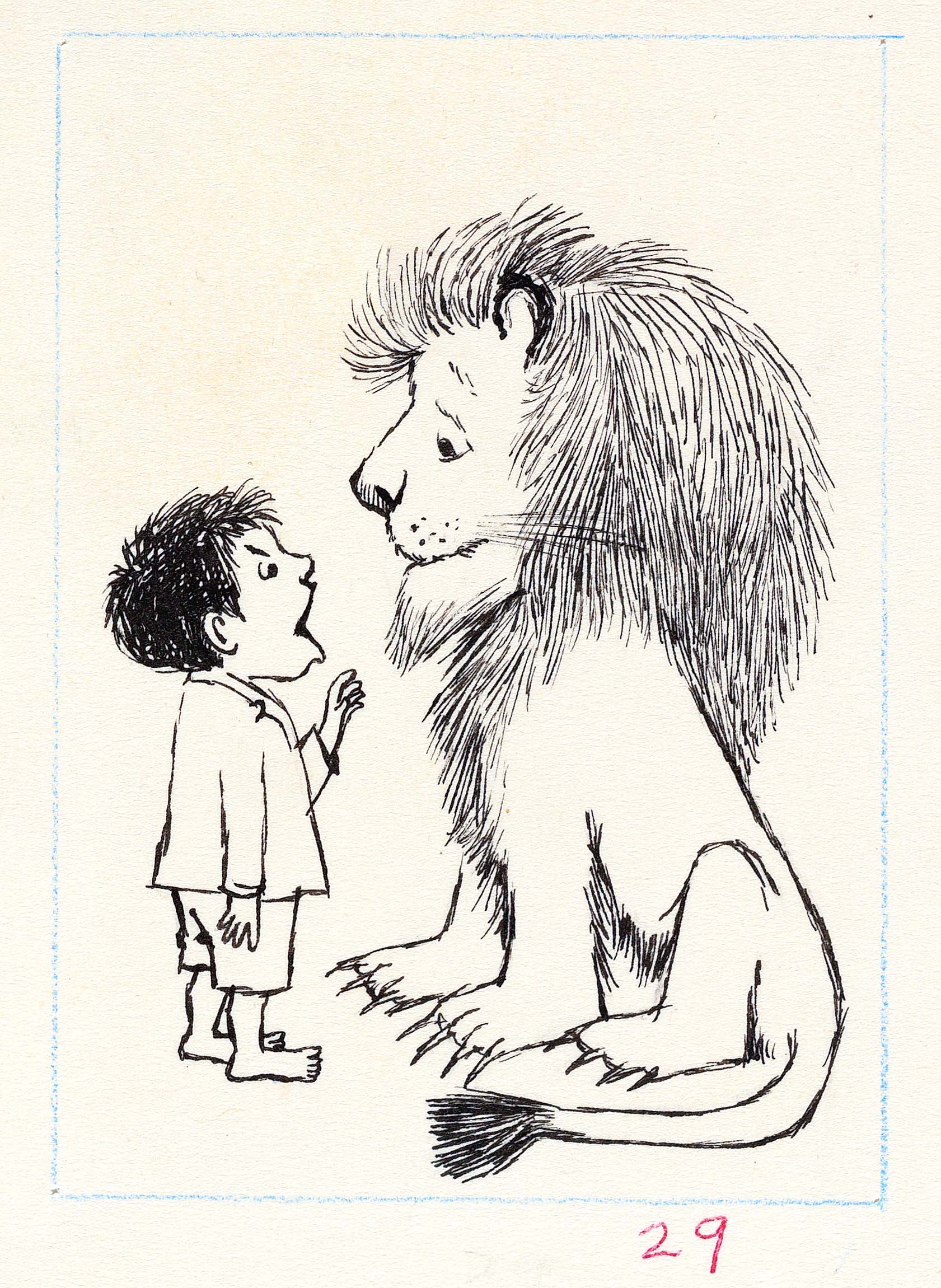

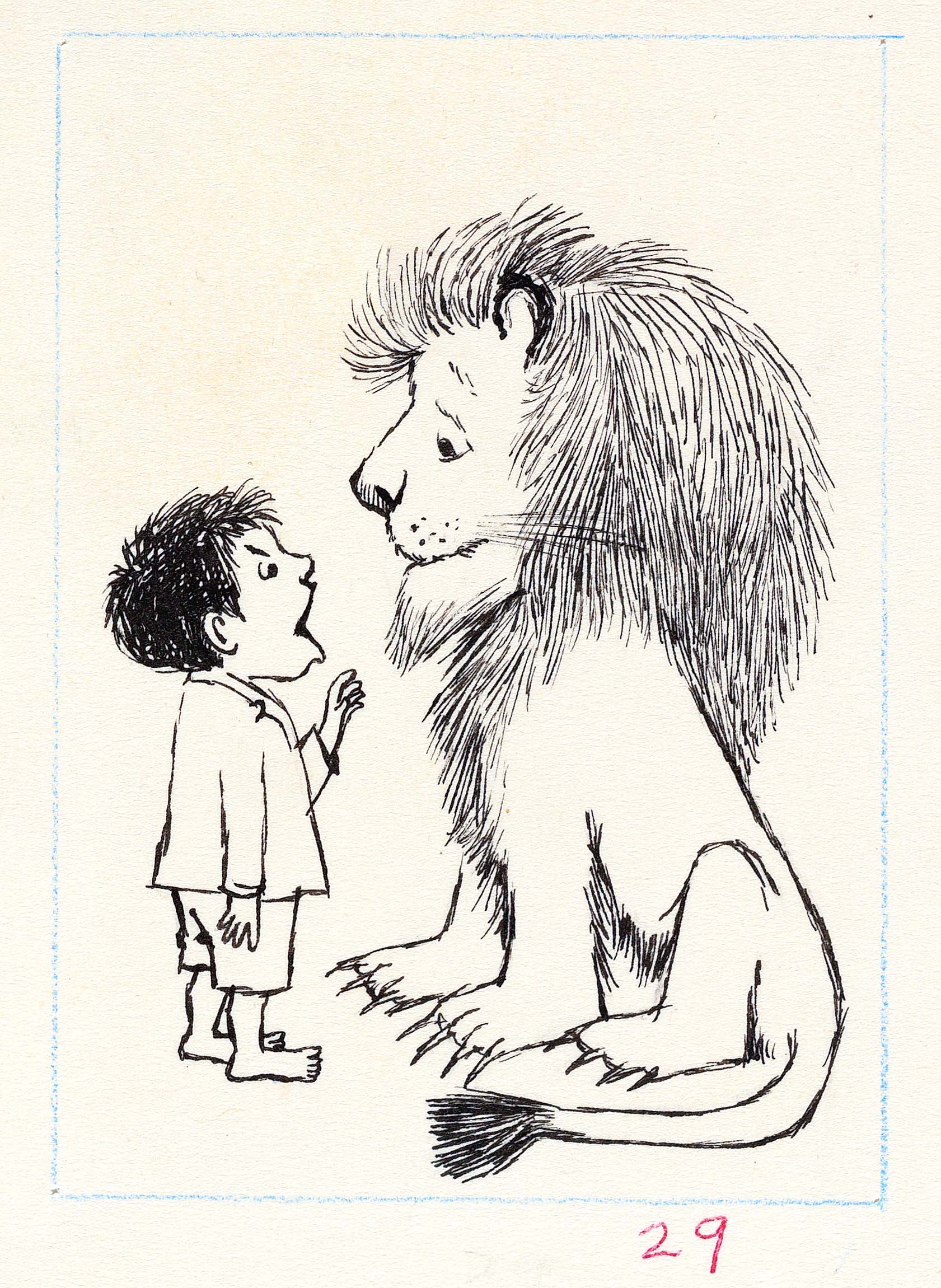

The figures in Sendak’s early work, such as the 1952 ink drawing, “Mashed potatoes are to give everybody enough,” from A Hole is to Dig: A First Book of First Definitions, share something of the sweet nature and joyous abandon in illustrators like Ernest Shepard and Jessie Willcox Smith. But the sense of poverty at the table full of happy, hungry, unsupervised children — Is this an orphanage? Are these refugees? — speaks to Sendak’s immigrant origins and deep connection to the sufferings of Jews in Europe. The heavy black outlines and deft crosshatching would become characteristics of his work — his drawings, at any rate — and these suggest affinities with the revival of the woodblock print in Europe and America. Ten years later, in the 1962 drawing, “Pierre,” Sendak’s style has evolved; it is more modern, embracing the cartoon, enhancing the dark outlines, and allowing the crosshatching to find its own freedom in the boy’s “Jules Feiffer” hair and the lion’s “Al Hirschfeld” mane (I found myself searching for ‘Ninas’ in the lines).

Yet, scarcely a year later, with the publication of Where the Wild Things Are in 1963, and the truly wild success that ensued, Sendak’s style is absolutely his own and the world he builds in the book is, somehow, exactly the sort of world we imagine Max would create in his room and in his mind, as if his room is an extension of his imagination. In Sendak’s watercolor and ink drawing, Max, in his costume — feline? vulpine? — roars through an imaginary moon- and star-drenched woods where the palms on the palm trees might be feathers and the flowers on the forest floor might be butterflies or snails. Every leaf and blade of grass shimmers, vibrating and alive, but the pastel palette softens the “wildness” of Max’s vision, almost as a signal that Max’s punishment will end and the supper that had been denied him will be there — “still hot.”

“Pierre” by Maurice Sendak, 1961-2, ink on paper, 4¼ by 3½ inches. ©The Maurice Sendak Foundation.

Where the Wild Things Are earned Sendak the coveted Caldecott Medal. He would go on to win the Hans Christian Andersen Award, the National Book Award, the Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal for American children’s literature, the National Medal of Arts, and the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award for children’s literature.

In the late 1970’s, Sendak began to take an interest in other media, adapting his own books for the stage and screen, and designing sets and costumes for plays and the ballet.

Eventually, Sendak would ask playwright Tony Kushner to write a new English-language version of Czech composer Hans Krása’s Holocaust opera Brundibár, which had been performed by children in the Theresienstadt concentration camp. Kushner would write the text for Sendak’s illustrated version of Brundibár, published in 2003. This is of special interest because Kushner would also publish another book in 2003, The Art of Maurice Sendak: 1980 to the Present, in which he describes Sendak’s insistence on treating children honestly in the following way: “But children both need and suffer revolution. They need freedom and routine, freedom and security. Art for children must not merely mirror, must not be satisfied simple to foment the growth that comes from freedom; art for children must organize as well. Sendak’s comprehension of this dialectic, and his masterful expression of it, account for part of his immense appeal to children and scholars alike.” This dialectic further mirrors the pairing of exuberance and terror that underpins all of Sendak’s work and subverts any surface sweetness in the books.

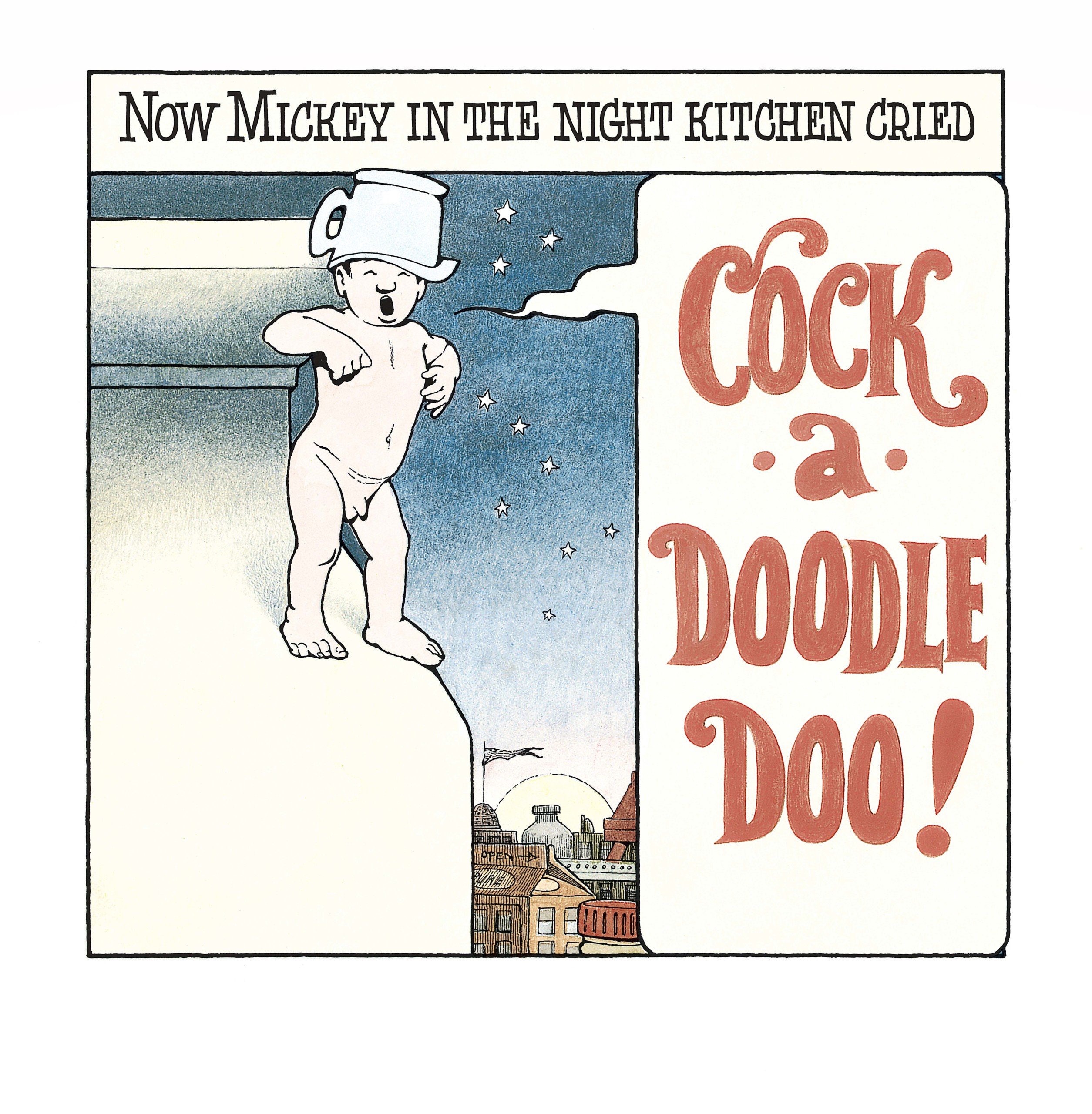

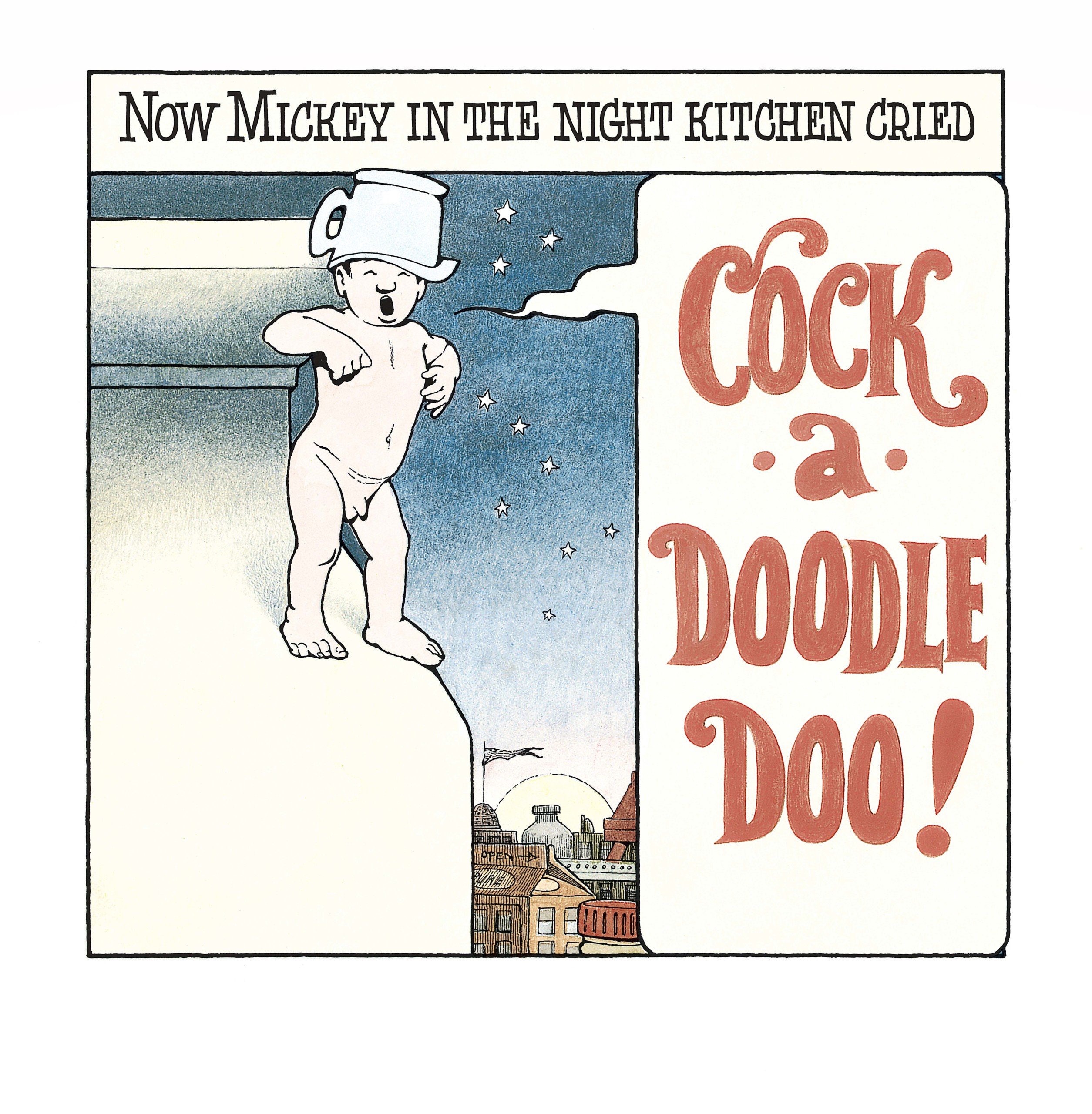

“In the Night Kitchen” by Maurice Sendak, watercolor and ink on paper as printed in color in Maurice Sendak, In the Night Kitchen (New York City: Harper & Row, 1970).

Honesty, more than once and in more than a few states, got Sendak into hot water with those who would ban books. In the Night Kitchen remains on the list of “most-banned and censored books” because of Sendak’s depiction of the character Mickey’s genitals as the boy stomps and storms across the pages. To add an adult aspect to the terror that young readers feel, the bakers who “accidentally” fold Mickey into their dough and nearly bake him bear strong resemblance to Adolf Hitler — though some attempt to soften this by asserting that they look more like comedian Oliver Hardy, of Laurel and Hardy, than Hitler.

In the illustrations from the 1967 book, Higglety Pigglety Pop!, and “Rosie and Buttermilk, her Cat,” the character studies for the 1973 cartoon, Really Rosie, something else that Kushner discovers and highlights in Sendak’s work emerges. As he writes, “Every good children’s book [is] a safe place for children to roam in, to encounter dangers in. A good book provides for children a realm of their own from which the aspiration of every child — to grow up — has not, a terrifying notion, been expunged.” Look at the child in the highchair, eyeing up the dog who has taken his place at the table and at Rosie, flouncing around in grown-up clothes. Their faces and gestures are adult. They are literally “trying on” the frowns and worries and woe-is-me masks, the personae of their parents and the adult world they are trying to figure out.

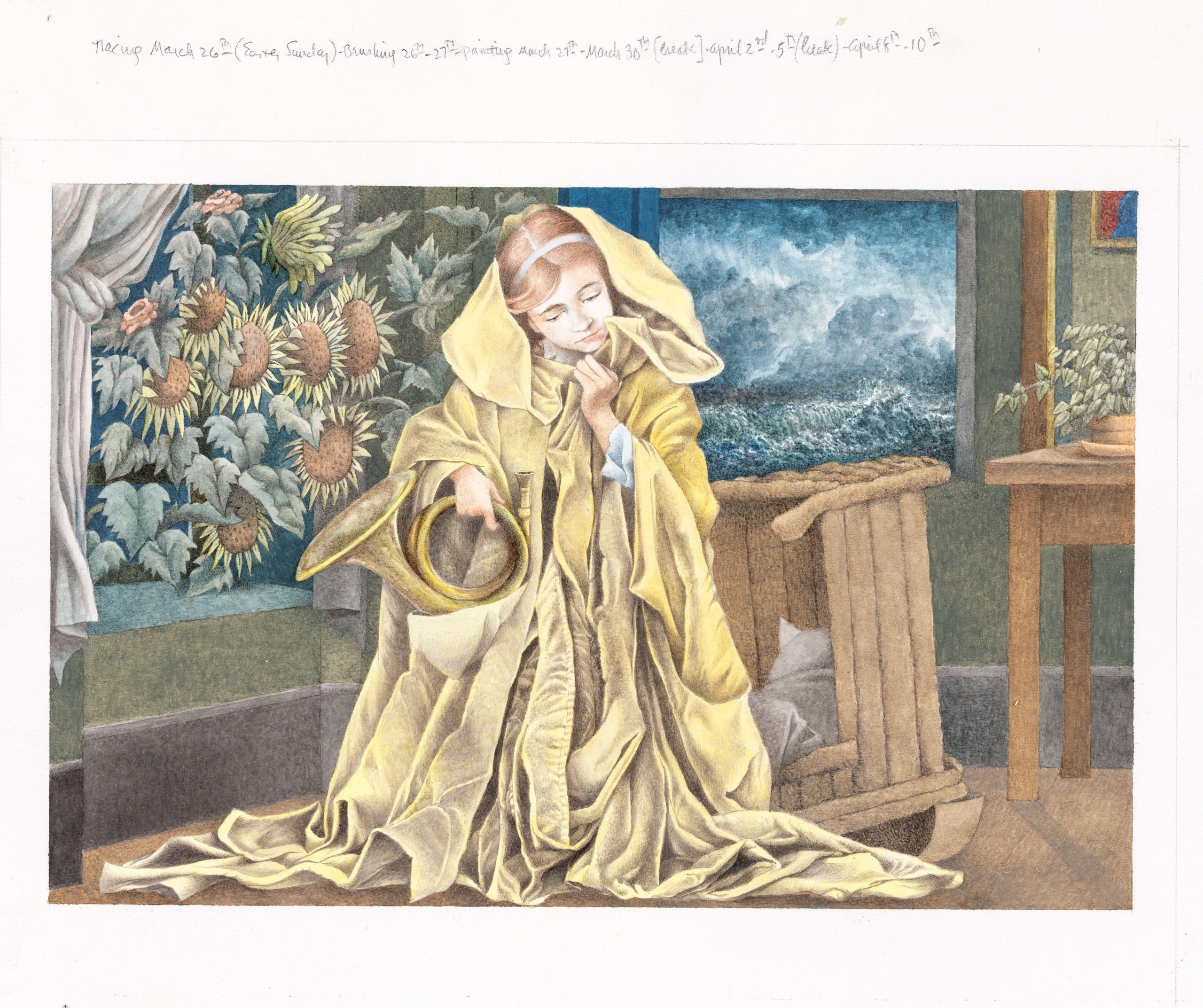

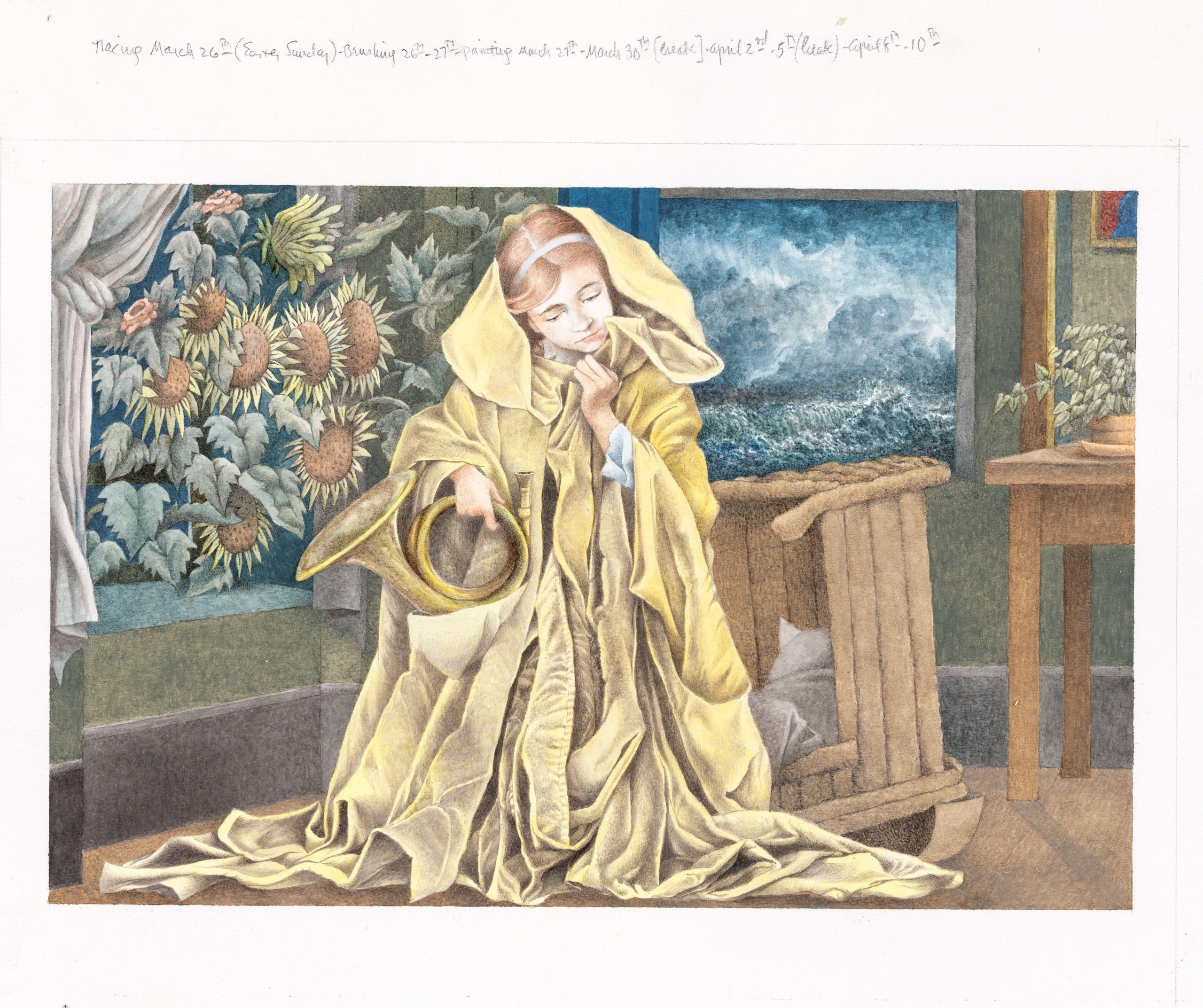

Drawing on his own memory of his terror of the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby, in Outside Over There, Sendak writes the kind of tale you might find in the Brothers Grimm. A young girl, Ida, tasked with taking care of her baby sister, must go on a perilous journey when the baby is stolen by goblins and replaced with a doll made of ice. After hearing the voice of her father, a sailor away at sea, on the wind, Ida rescues her sister — from goblins who turn out to be babies themselves — and all is well, but the story seemingly takes its toll, revealing a world in which parents are often away or busy and cannot always protect and spare children from the dangers and evils that arise. Sendak’s notes for Outside Over There, as Kushner indicates, and many others concur, state that his “artwork for Outside [Over There] was, from its earliest inception, inspired by the paintings of the early German Romantic painters Philip Otto Runge and Caspar David Friedrich.”

“Outside Over There” by Maurice Sendak, 1981, watercolor and graphite on paper, page: 15 by 26 inches; image: 6-1/8 by 9-3/16 inches. ©The Maurice Sendak Foundation.

Sendak’s art for the story is stylistically quite different from his other books. Knowing his inspiration, the link to Grimm’s Fairy Tales, also a product of German Romanticism, strengthens. Further, in the watercolor shown on these pages, Sendak’s interest in Friedrich and Runge becomes apparent. As in their work, the picture plane is crowded, claustrophobic with repeated forms. The sunflowers and leaves intruding themselves through the window at left are spiky, like eyes and ears spying and eavesdropping, as if they were silent conspirators to the theft of the baby, whose empty, upturned cradle sits below the window.

Everything is in focus, near and far, sending whatever aspects of realism obtained here into the realm of the surreal. The cloak Ida wears all but smothers her in a turbid labyrinth of crevasses not unlike the icebergs in Friedrich’s 1824 painting, “The Sea of Ice” or the cold, contorted landscape in the 1818 oil, “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog.” Lastly, the view out the window over Ida’s left shoulder, the actual “outside over there,” is straight out of Friedrich and Runge, a romantic landscape with a cloud-hung mountain, dark forest and robber caves — all the hallmarks of terror and attraction that Edmund Burke deemed “the sublime.”

In the end, Sendak’s own experience as a child, informing his art and writing, reminds us that lying to children, trying to make everything seem okay even when it isn’t, comes with a price — trust. At the start of this essay, I suggested that grownups attend “Wild Things: The Art of Maurice Sendak” at the Denver Art Museum by themselves. Now, having come to the end, I’m not so sure. I think I’d rather go with a few kids, even my own grownup kids, just to hear what they remember, what they think and what they have to say — in all their interrupting, overlapping enthusiasm. I think that’s what Maurice Sendak would want, too. Let the wild rumpus start.

The Denver Art Museum is at 100 West 14th Avenue Parkway. For information, 720-865-5000 or www.denverartmuseum.org.