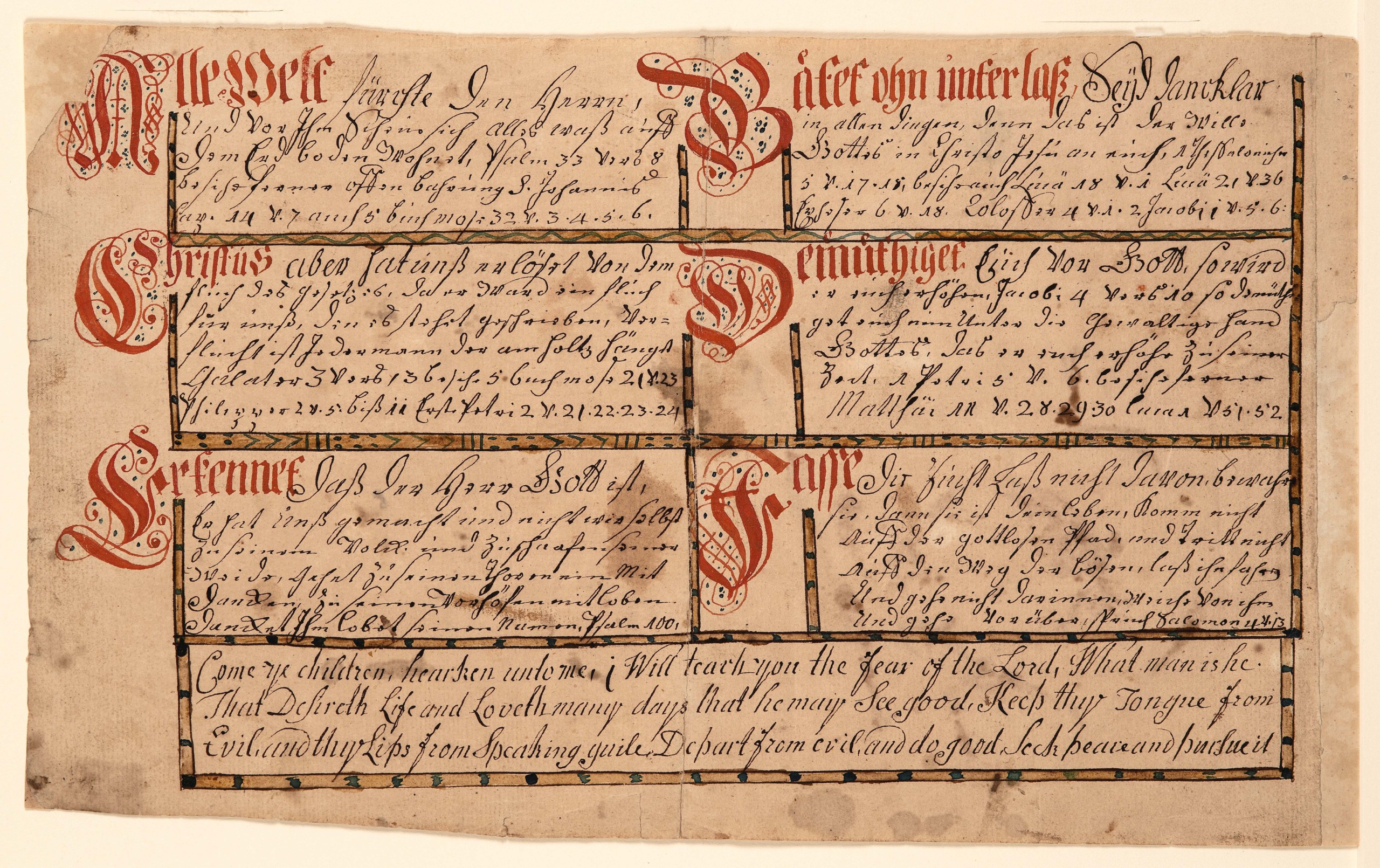

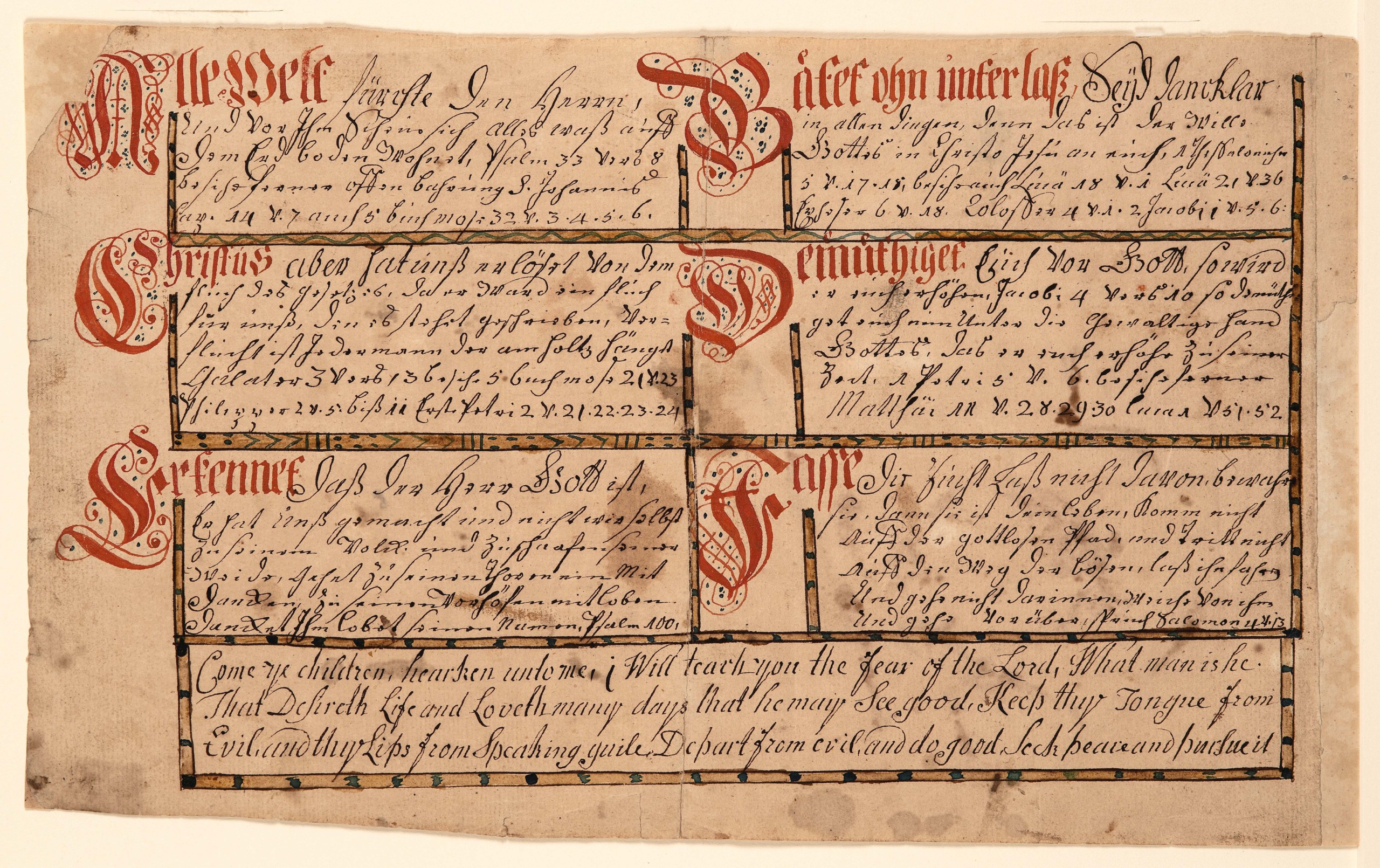

Cutwork for John Mayer by Isaac Faust Stiehly (1800–1869), Upper Mahantongo Township, Schuylkill County, Penn., 1841, watercolor on paper. Collection of Robert and Katharine Booth.

By Madelia Hickman Ring

TRAPPE, PENN. — To celebrate the fifth anniversary of Historic Trappe’s Center for Pennsylvania German Studies (CPGS), executive director Lisa Minardi pulled out all the stops, assembling from nearly a dozen private collections a selection that includes many of the “greatest hits” of Pennsylvania German folk art known. In “Valley Culture: Constructing Identity Along the Great Wagon Road,” various forms of Pennsylvania German folk art — fraktur, boxes and painted furniture — are explored to show how these artifacts of daily life were transformed by German settlers moving west from Perkiomen Valley in Southeastern Pennsylvania to the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia.

Curated by Lisa Minardi and Christopher Malone, who recently joined Historic Trappe as its curator, the show received lead support from Downingtown, Penn., auctioneers Pook & Pook, with additional support from Jane and Gerald Katcher, Robert and Katharine Booth, Susan and Steve Babinsky, Steve and Jenifer Smith, the American Folk Art Society, Peggy Pace Duckett and Brett Robbins and Renata Ferrari. Jeffrey S. Evans and Associates sponsored the exhibition’s Tavern Night preview party on September 26.

With its mission and devotion to the study of Pennsylvania German material culture, and semi-permanent exhibitions that display every manner of objects, from furniture to ceramics to ironwork and textiles, the CPGS was uniquely positioned to be the ideal venue for the show. Minardi, who had long been hoping to do an exhibition on painted fraktur and painted furniture, noted the timing of the show coincided with some key artifacts becoming objects available to borrow. The exhibition is another feather in the cap of Historic Trappe and CPGS, which received early support from Joan and Victor Johnson and William K. du Pont, as well as a critical long-term loan partnership with the Dietrich American Foundation.

Alphabet, attributed to Christopher Dock (d 1771), Skippack or Salford, Montgomery County, Penn., 1762, ink and watercolor on laid paper. Dietrich American Foundation, 7.9.368a,b.

The study of Pennsylvania German material culture has rich traditions in the scholarship of early American decorative arts and the exhibit not only breaks new ground but provides viewers with new perspectives.

Minardi elaborated. “‘Valley Culture’ builds in part on several previous shows, in particular ‘Paint, Pattern & People’ at Winterthur in 2011, but goes into much greater depth and explores additional locales not previously examined in earlier exhibitions. It’s unique in comparing the distinct material culture of six different regions: the Perkiomen Valley, Tulpehocken Valley, Cocalico Valley, Mahantongo Valley, Brothers Valley and Shenandoah Valley. The show moves from southeastern Pennsylvania to central Pennsylvania to western Pennsylvania and then Virginia, following the Great Wagon Road that Pennsylvania German settlers took as they moved west and then south — bringing artifacts and ideas with them. The combination of fraktur and furniture in the exhibition is also rare — most shows focus on one or the other but don’t give equal weight to both.”

The importance of the show cannot be overstated, as suggested by two leading experts in the field: Woodbury, Conn., dealer David A. Schorsch, and Mount Crawford, Va., auctioneer Jeffrey S. Evans, both of whom have been instrumental in handling many of the works in the show.

“This exhibition is very special,” Schorsch said. “I’m not sure I’ve ever seen an assemblage in my life that has the depth and quality that’s in this show. It’s remarkable that Lisa pulled it together in such a short period of time, bringing in some great discoveries and iconic masterpieces and making groupings of things so you can make comparisons. It really is a unique opportunity to see things that are largely privately owned. To see these objects in commonality with other objects by the same makers is incredibly important and changes your perspective. I was at the opening and it’s very impressive to see how much support Lisa and Historic Trappe have received from the local community; I don’t think you can underscore how important that is.”

Slide-lid box, probably Lancaster County, Penn., circa 1780–1810, white pine, paint. Collection of Jane and Gerald Katcher.

Evans’s praise was equally effusive. “Lisa and her staff have assembled a breathtaking exhibition of important regional folk art for this show, some of which are on public view for the first time. The proximity of the objects allows a rare opportunity to closely compare and study the ethnocultural aesthetics and symbolism of close-knit communities along the Great Wagon Road. I would argue that the main folk art gallery exhibits more great paint per square foot than any exhibition ever mounted!”

A few revelations occurred to Minardi during the course of pulling the exhibition together, largely afforded by the opportunity to view numerous examples by the same artist or from the same region side by side. Similarities between pieces made by Bucks County woodworker John Drissel (1762-1846) became apparent, while differences between fraktur made by Henrich Otto and three of his sons was a surprise to Minardi.

These geographical regions created divisions within the show, beginning with the Perkiomen Valley, which runs through Central Montgomery County, along Perkiomen Creek, a 37-mile tributary. The valley was settled as early as the early 1700s by members of numerous faiths: Lutherans, Reformed, Mennonites, Brethren, Schwenkfelders, Moravians and Roman Catholics. Notable artifacts from this region include a circa 1805 fraktur of Adam and Eve attributed to Durs Rudy Sr (1766-1843), a Swiss immigrant, fraktur artist and Mennonite teacher. Predating this by more than 40 years is an ink and watercolor alphabet attributed to Mennonite schoolmaster Christopher Dock (d 1771), who is one of the earliest documented fraktur artists. His 1769 pioneering treatise on childhood education provided students with examples to copy and recorded his practice of rewarding good students with “a flower drawn on paper or a bird.” Birds and flowers are also seen as decorative motifs on a blanket chest made for Daniel Eisz in 1795 that is a particularly impressive example of a large group known.

“Adam and Eve Were Led Astray by the Snake in Paradise” attributed to Durs Rudy Sr (1766–1843), probably Skippack, Montgomery County, Penn., circa 1805, watercolor and ink on laid paper. Collection of Jane and Gerald Katcher.

Next to Perkiomen Valley, Cocalico Valley in northern Lancaster County encompasses 10 municipalities: the boroughs of Adamstown, Akron, Denver and Ephrata, as well as the townships of East and West Cocalico, Clay, Ephrata, West Earl and a portion of Earl. First settled by the Lenape and Susquehannock people, the area drew immigrants from Switzerland in the early Eighteenth Century. Boxes — both large and small — are among the most well-known forms to survive from this time and region. Some were made by an unidentified artist who used a compass to outline the painted decoration between circa 1820 to circa 1850. Others were embellished with detailed landscapes, including those by Jonas Weber (1810-1876). A birth and baptismal certificate for Georg Miller attributed to prolific fraktur artist Friedrich Krebs (1749-1815) is a tour de force, featuring animals, birds and cut out pictures of human figures and saints.

The exhibit continues into Tulpehocken Valley, a 322-square mile area that extends across what is now Western Berks and Eastern Lebanon counties and is bounded by the Blue Ridge and South Mountains. Prominent survivors from this area were blanket chests, portraits by Lebanon County itinerant artist Jacob Maentel (1778-1863) and fraktur by Henrich Otto (1733-circa 1799), Friedrich Speyer, Daniel Otto (circa 1770-circa 1820), William Otto (1761-1841) and Jacob Otto (circa 1762-circa 1825).

The Mahantongo Valley is represented by a newly discovered chest from the Knorr family that has never been published and is a standout of the exhibition; it features an unusual use of vibrant colors and the presence of female figures painted on the sides. Scissor-cut pictures — known as scherenschnitte — are appealing survivors and several are featured, including ones by Isaac Faust Stiehly (1800-1869), an itinerant German Reformed minister in Upper Mahantongo Township who was also a stonecutter, millwright, farmer and artist.

Chest of drawers, Mahantongo Valley, Northumberland and Schuylkill counties, Penn., 1829, yellow pine, tulip poplar, paint, brass. Collection of the Knorr Family.

The Great Wagon Road turned south in Western Pennsylvania, in Brothers Valley, in what is now Somerset County, north of the Maryland border. Sparsely populated prior to the arrival in the late 1700s by the Mennonites, Quakers and Brethren (also known as German Baptists or Dunkers), surviving objects reflect dazzling displays of shapes and color combinations.

The exhibition reaches a climactic conclusion in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, geographically defined by the Allegheny Mountains on the west and the Blue Ridge Mountains on the East and encompassing the Virginia counties of Frederick, Clarke, Shenandoah, Warren, Rockingham, Page, Rockbridge and Augusta, as well as Berkeley and Jefferson counties in West Virginia.

Two of the area’s most famous artists — Johannes Spitler (1774–1837) and Jacob Strickler (1770–1842) — are recognized for their bold, occasionally abstract designs and a color palette with predominant reds, whites and blues. A circa 1800 hanging cupboard made for Strickler and attributed to Spitler is the only known example of the form but the leaping stag decoration can be seen on a tall-case clock and other forms of Pennsylvania German folk art.

Hanging cupboard made for Jacob Strickler, attributed to Johannes Spitler (1774–1837), Shenandoah (now Page) County, Va., circa 1800, yellow pine, paint, brass. Collection of Jane and Gerald Katcher.

When asked what she wants viewers to take away from the show, Minardi was candid. “My hope is that visitors to this exhibition will be truly inspired by the beauty, creativity and craftsmanship of the objects featured in the show. Each piece is unique and exceptional in its own way. Even those who think they’re familiar with Pennsylvania German folk art will come away with a renewed appreciation for these objects. I also hope that the show will inspire people who know nothing about the topic to fall in love with these this genre — American folk art at its finest.”

“Valley Culture, Constructing Identity Along the Great Wagon Road” will be on view in the Center for Pennsylvania German Studies at Historic Trappe until August 17. A catalog is in production and will be published by the end of the year.

Historic Trappe’s Center for Pennsylvania German Studies is at the Dewees Tavern, at 301 West Street, Trappe, PA 19426. For information, 610-489-7560 or www.historictrappe.org.