“Lady in A Fancy Interior” by Rogelio de Egusquiza Barrena, Spain, 1874, oil on panel.

By Z.G. Burnett

NEW YORK CITY — The Hispanic Society Museum & Library (HSM&L), the primary institution dedicated to the preservation, study, understanding and enjoyment of the arts and cultures of the Portuguese- and Spanish-speaking world, hosts a groundbreaking new exhibition, “A Room of Her Own: The Estrados of Viceregal Spain.” The exhibition opened in the museum’s main court on November 7, and runs through March 2. “A Room of Her Own” delves into the rich, forgotten history of the estrado, a women’s private drawing room found throughout the Hispanic world. “A Room of Her Own” explores the estrado’s profound impact on feminine self-expression and physical autonomy, as well as collecting practices, sociability and intercultural exchange.

This exhibition traces the evolution of the sala de estrado from Islamic Al Andalus to the Americas, where it flourished until the collapse of the Spanish Empire. Defined in the Diccionario de Autoridades (Madrid, 1732) as the “set of furniture used to cover and decorate the place or room where the ladies sit to receive visitors,” the estrado was a room or designated area where women engaged in elaborate social practices and displayed their collections of valuable objects from the Americas, Asia and Europe.

“The word estrado has mysterious origins,” explained Alexandra Frantischek Rodriguez-Jack, assistant editor and graphic designer at the HSM&L and guest curator of the exhibition. “It’s a women-coded word, which could have arisen from a certain type of harem but also possibly from the display of a collection.” In prime documents, an estrado was not necessarily gendered until the Fourteenth Century. During the Spanish Golden Age (circa 1492-1659) it was “an incredible metaphor for women’s extravagance and idleness.” The last reference Rodriguez-Jack could find in this context was from the Nineteenth Century, and in today’s Spanish, the word means “witness stand” or “stage platform.”

Four-panel screen, Iturbide period, Mexican, 1820s, painted canvas and wood frame.

The well-appointed estrado has long been a focal point of opulence and intrigue in travel accounts, inventories, legal records and works of fiction. Designed for upper-class interiors and inhabited by elite women of European, Indigenous American and West African descent, the estrado paradoxically becomes a locus of female agency and subversion within a place of confinement. The exhibition engages a comprehensive array of archival sources and objects to question the values historically imposed on gender stereotypes and behaviors and highlights the estrado’s importance as a symbol of power, wealth and virtue.

Curated by Rodriguez-Jack and Margaret E. Conners McQuade, deputy director and head of collections at the HSM&L, this exhibition presents decorative objects, paintings, rare books and engravings from its unrivaled holdings in an entirely new light, with the majority works from its roughly 750,000-piece collection to be exhibited for the first time. Rodriguez-Jack researched dowry letters, inventories and other documents to match up each object in the exhibition, showing just how far some objects traveled to these women’s collections. “Though many pieces were listed in contemporary records as being from Far East in Asia, many were chinoiserie made in Spain.” Yet, the Americas were a hub for Manila galleons from China and Japan, and the exhibition displays objects from Turkey, Goa and Japan, among other countries. Each artifact is meticulously contextualized through extensive research, offering visitors a nuanced understanding of women’s daily lives in the early modern world.

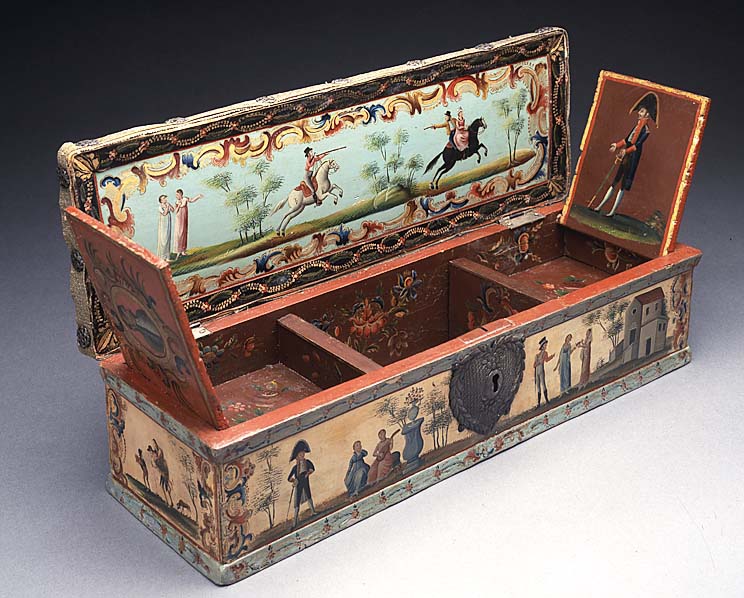

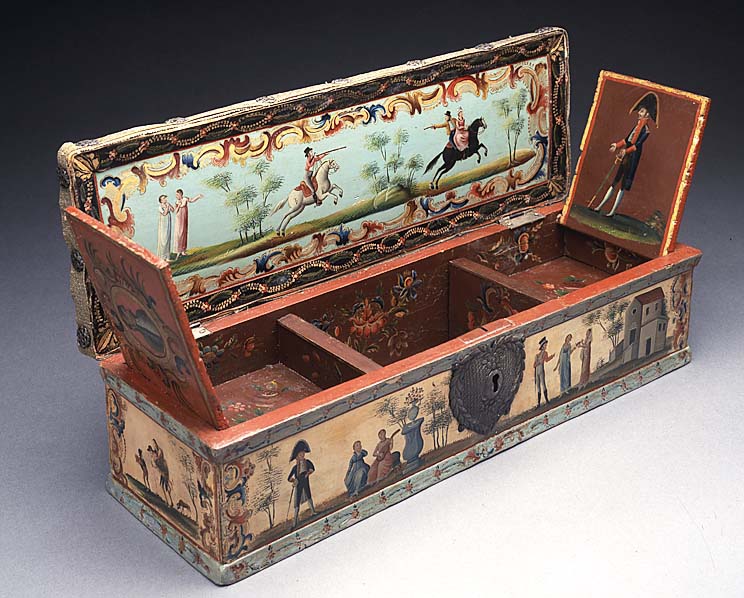

Sewing box, Michoacán, Pátzcuaro, Mexico, 1800, Mexican lacquer and paint on wood with silver lock plate, silk and brass tacks.

“It’s a long story,” said Rodriguez-Jack, when asked what inspired this exhibition. “My family is Latin American and European, so I decided to study decorative arts during the colonial period of Latin America during my MA program, only to be told that ‘there were no decorative arts in Latin America.’” Rodriguez-Jack persisted, earning a fellowship at the HSM&L and completing her thesis on estrados in Spain and Latin America from the late medieval period to the Nineteenth Century, specifically “ways this tradition passed from the Iberian Peninsula to the New World and how it affected art and design as an original, localized and unique practice by examining guilds in particular indigenous and malato craftspeople.”

“The exhibition emerged from people telling me it wasn’t possible,” she added.

“This exhibition is the first of its kind to shed light on the estrado’s peculiar role as a platform of gendered power dynamics and female agency, while also tracing the trajectory of regional variations of the estrado and women-led collecting practices from the Iberian Peninsula to the Spanish Americas,” said Rodriguez-Jack. “Significantly, this exhibition highlights the daily lives, habits and domestic interiors of non-European women in the Spanish-speaking world, an area which historically has been overlooked.

Beaker, Mexico, Jalisco, Tonalá, 1650, red-slipped earthenware with embossed decoration.

“These women outfitted their estrados with expensive art objects and bespoke small-scaled furnishings to create these incredibly opulent and eclectic, maximalist spaces. The exhibition features a number of hidden gems from the Hispanic Society’s permanent collection, while demonstrating how these works interacted with each other in situ and facilitated various activities, ranging from bobbin lacemaking to witchcraft.”

“A Room of Her Own” explores localized patterns of elite female consumption, domestic display and collecting practices, culminating in the Eighteenth Century concept of sociabilidad (“sociability”) associated with gendered consumption of luxury goods from the Americas, Asia and Europe. From the estrados of formal reception rooms to private bedchambers, women curated magnificent collections that bridged continents and cultures, bringing the outside world into these enclosed domestic spaces.

When asked if she has her own favorite object in the exhibition, Rodriguez-Jack mused how each is so different, there are so many mediums present, that it’s hard to choose just one. Her tentative choice is a writing cabinet from Oaxhaca, showing Flemish-style surface engravings. These were executed with the Indigenous zulaque technique, using a dark pigment to accentuate the carvings. The cabinet had been with its owner since the mid Nineteenth Century. “They thought it must have been Spanish-made because the craftsmanship and decoration was so fine,” the curator said. It then was discovered that it showed Indigenous craft construction by a local worker, a “Mexican take” on the Spanish style. Many such objects exist, presumed to be European but showing traditional techniques, sometimes even specific flora and fauna from the Americas. Rodriguez-Jack continued, “These are the misconceptions we’re trying to overturn.”

Writing cabinet, Villa Alta de San Ildefonso, Oaxaca, Mexico, 1650-1700, marquetry (zulaque), mixed wood with wrought iron hardware.

Since falling out of fashion in the mid Nineteenth Century, the sala de estrado has been largely forgotten, and there are no comparable exhibitions that delve into the enigmatic history of the estrado and its contents. The exhibition embraces current scholarly discourse through the material culture of gendered spaces, cross-cultural encounters and marginalized populations, while taking a thoughtful, intersectional approach to gender, race/ethnicity and socio-economic class in the Hispanic world.

“There’s no real modern equivalent of an estrado,” said Rodriguez-Jack. “Maybe a man cave, but for women?” During the time of the estrado, wealthy women were rarely seen by anyone outside of their family or people in the same socioeconomic class. Before the Eighteenth Century, girls were either educated in convents or by their mothers at home, adding another dimension to the insularity of the estrado specific to this time period. Because of advancements in women’s rights, opportunities and overall improvements in autonomy, today there are few examples of such an “ambivalent, cloistered, designated female space.”

In conjunction with the exhibition, the Hispanic Society’s Education Department will host a series of allied programming, including live concerts featuring classical music from the Baroque period composed by women of Iberian descent, symposiums, family activities, guided tours and panel discussions. Both the exhibition and related programming are free to the public. “A Room of Her Own” will engage with a diverse audience by fostering a dialogue around themes of culture and female agency, autonomy and identity-creation in the estrado.

The Hispanic Society Museum & Library is at 3741 Broadway. “A Room of Her Own: The Estrados of Viceregal Spain” will be on view through March 2. For information, 212-926-2234 or www.hispanicsociety.org.