Offering dish with chariots, made in Athens, Greece, 500-400 BCE, silver with gilding. Found at the necropolis near Duvanlii-Chernozemen, Bulgaria. Regional Archaeological Museum, Plovdiv. Todor Dimitrov photo. VEX.2024.2.121.

By James D. Balestrieri

MALIBU, CALIF. — Winners write the histories. Isn’t that how the saying goes? If it’s true, then the winners define the losers. And one of the ways winners define losers is to “other” them, make them seem other than and less than — less than civilized, less than human, other than, well, us. One of the words that starts the ball down the slippery slope is “barbarian,” a word that merely means, in its original sense, “bearded.” Barbarians are what the Romans called — in Latin, where the word comes from — those who lived in and came from the north and elsewhere. The smooth-shaven versus the bearded — sounds like a Dr Seuss book.

But the concept is far older, as old as the first boundary drawn by the first culture that had an awareness of itself as unique and separate from others.

Thrace is just such a place, one of those places that is no more, so, in fact, it’s ancient Thrace, a “barbaric” territory north of the Aegean Sea, northeast of civilized Greece and northwest of imperial Persia and very much caught between both. On today’s map, Thrace overlays, or, perhaps more truthfully, lies under Bulgaria and parts of present-day Greece, Turkey and Romania. Thrace is the subject of “Ancient Thrace and the Classical World: Treasures from Bulgaria, Romania and Greece,” on view through March 3 at the Getty Villa in Malibu.

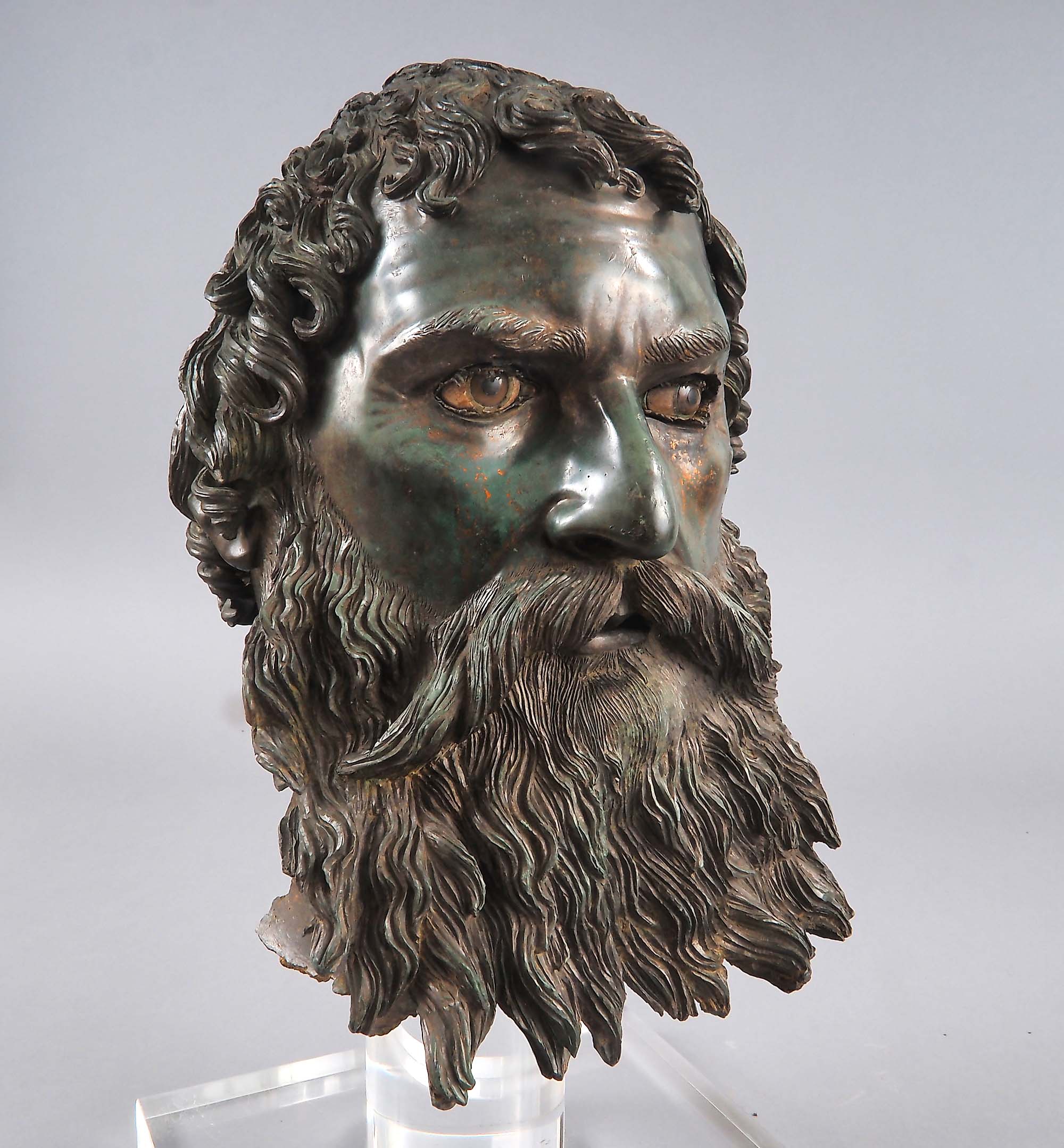

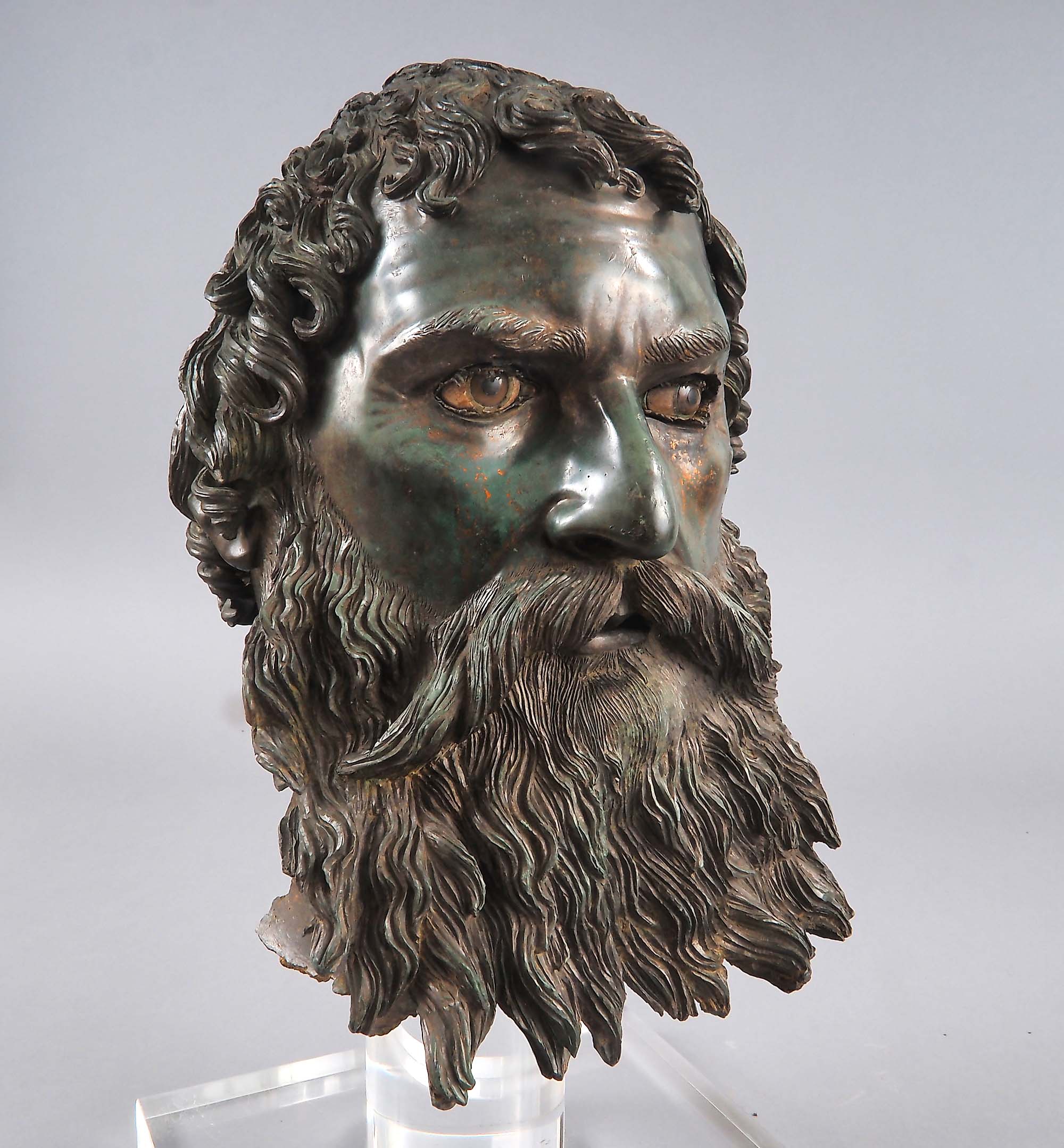

Portrait of King Seuthes III, 310-300 BCE, bronze, with copper, alabaster and glass for eyes. Found in the Golyama Kosmatka burial mound, near Shipka, Bulgaria. National Archaeological Institute with Museum – Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia. Todor Dimitrov photo. VEX.2024.2.159.

I didn’t know much about Ancient Thrace other than having a vague notion of where it was, that its people were seen as an equine people and that Orpheus, whose music was so magical that he was able to descend into Hades and, almost, rescue his love, Eurydike, was said to have hailed from Thrace. As I went through the heroically researched catalog and the astonishing objects on display, I watched the adjective “barbarian” fall away from yet another culture. Finding that so-called “barbarian” cultures are anything but is one of the added dividends of writing essays for this publication. I also watched the fall of the name Thrace, which, as it turns out, was a name assigned to the region by the Greeks, Persians and Romans to define a loose amalgam of as many as 50 separate tribes united, perhaps, by a common language — which we do not fully understand — and some commonalities of dress, manner and weaponry. The word “Indians” sprang immediately to mind. What united Thrace was the desire of powerful neighbors to exploit her mineral resources — copper, gold and tin, colonize her Black Sea territories and fold her skillful warriors into their armies. At times over some seven centuries, the various peoples of Thrace traded and intermarried with their occupiers; at other times they sought autonomy, rose up and resisted.

As always happens with crossroads cultures, some of the peoples of Thrace — especially those in the south, closest to Greece, those closest to the “overseas” Greek societies in Thrace, and those Thracian nobles who later served the Romans when their empire succeeded the Greeks — adapted to and adopted some of the customs of their conquerors, becoming “Hellenized” or “Romanized” barbarians, figures of fun on the Athens stage even as their “barbarism” became a source of fascination, so much so that, as Matthew A. Sears writes in his catalogue essay, “the comic playwright Aristophanes coined the term “Thrace-haunters” to describe those who habitually haunted the lands to the north of the Aegean.”

Relief with two Thracians, made in Achaemenid Iran, 500-480 BCE, limestone. Found at Persepolis, Iran. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum. Image: bpk Bildagentur / Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum. Photo: Olaf M. Teßmer/Art Resource, N.Y.C. VEX.2024.2.6.

These Thrace-haunters recall the Crusaders, later colonizers, and adventurers like Lawrence of Arabia — Sears singles him out in particular — who were, as Edward Said might have said, “Orientalized” as they “went native.” Sears goes on: “We know most about the Thrace-haunters who were otherwise famous political and military leaders. Thrace seems to have offered such men opportunities for wealth, power and military adventure that an increasingly egalitarian Athens did not — just as the “Wild West” did for certain Americans in the Nineteenth Century.” Even the “frontier fashion” of the Thracian peltasts — light infantry whose weaponry, tactics and speed would become essential aspects of Greek and, later, Roman, armies — “alopekides (fox-skin caps), chitons covered with long cloaks called zeirai, and embades (tall fawn-skin boots),” make their way into Athenian life and onto vases depicting myths whose origins they located in the north.

After his failure to rescue Eurydike, Orpheus returns to Thrace, where his music so charms the men that the women of Thrace — you can tell they are Thracian by their dress — carve him up and send his head downriver and out to sea where it fetches up on an island and begins to sing prophecies. Dionysus, too, famous god of wine, frenzy and ecstasy, incarnates in Greek literature as a Thracian product. The thing is, neither Orpheus nor Dionysus appear to have Thracian origins. What we know of the religion of the territory suggests that the Thracians didn’t believe in the separation of the soul from the body. Indeed, the majestic and beautiful tombs of their rulers and members of the ruling class do not contain the bodies of the deceased — they are purely symbolic.

Helmet with an appliqué of Athena, 350-250 BCE, bronze, silver with gilding. Found in the Golyama Kosmatka burial mound, near Shipka, Bulgaria. Iskra Historical Museum, Kazanlak. VEX.2024.2.62–.63.

All of which leads to the art itself. Found in the Golyama Kosmatka burial mound, near Shipka, Bulgaria, is the “Portrait of King Seuthes III” (310-300 BCE). The catalog entry states that, “The level of quality further suggests that the portrait — together with the full statue — was produced by a Greek workshop as a royal commission from the Odrysian court.” In a power vacuum on the Green peninsula, the Odrysian Kingdom had formed in southern Thrace. For centuries, the Odrysians maintained their autonomy even as they themselves Hellenized. Thus, the astonishingly beautiful and realistic portrait of King Seuthes III, whose identity is confirmed by comparison to numismatic portraits and inscriptions, simultaneously captures the authority of the king, his wealth, his relationship with Greece, and the Greek perception of Thracian “wildness.” He even sports an unruly “barbarian” beard that seems to be blowing in the cold north wind — Boreas, that had its source, according to the Athenians, in the Thracian mountains.

Pieces in the exhibition that employ the panther or griffin motif, such as “Wine Cup with Lion-Griffins” (400-300 BCE), “Relief with a Panther” (400-350 BCE) and “Jug with a Goddess on a Panther” (400-300 BCE) show the influence of Achaemenid Persian iconography, a consequence of the Persian King Xerxes I enlisting the Thracians as allies and using their territories as a stepping stone on his way to an invasion of Greece in 480 BCE. When the Greeks defeated Xerxes, he retreated through Thrace, leaving, as the exhibition wall text states, “the Achaemenid practice of using gold and silver vessels at lavish banquets as a symbol of aristocratic status.”

Three-part vessel, 1500-1000 BCE, gold. Found near Valchitran, Bulgaria. National Archaeological Institute with Museum – Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia. Todor Dimitrov photo. VEX.2024.2.148.

Earlier objects from Bronze Age Thrace, such as “Three-Part Vessel,” created circa 1500-1000 BCE, and discovered in 1924 as part of the Valchitran Treasure, partake of the abstract geometry that characterizes works in cultures throughout the Mediterranean and the Near East. With its trio of symmetrical, leaf-shaped bowls with concentric engravings, “Three-Part Vessel” exhibits an incredible sophistication. The soldered electrum tubes that connect the bowls display astonishing technical skill. As with so many objects from this era, especially those from the area we call Thrace, the function of Three-Part Vessel remains a matter of speculation. Perhaps because of this, we feel free to regard it from our post-modernist perch — Three-Part Vessel would fit right in with Scandinavian design post-World War II.

But mystery is the watchword with Thrace and Thracian objects, as epitomized by the libation dish “Phiale Mesomphalos” (325-275 BCE). To quote the catalog, “The omphalos is surrounded by 12 rosettes, followed by a circle of 24 acorns, followed by three rows, each with 24 heads of Black African men of increasing size.” Part of the Panagyurishte Treasure, which has been interpreted variously — and contentiously — since its discovery in Bulgaria in 1949, the progression of the figures on the Phiale Mesomphalos from acorn to head is almost Escher-like. These “phialai aithiopides” (Ethiopian dishes) were offered to Nemesis and Athena, though their specific ceremonial use remains elusive. Where they came from in Greece and why they ended up in Thrace is also an open question. The obscure beauty of the piece, however, is not.

Phiale Mesomphalos (offering dish), 325-275 BCE, gold. Found in Panagyurishte, Bulgaria. Regional Archaeological Museum, Рlovdiv. Todor Dimitrov photo. VEX.2024.2.125.

So there was no Thrace and the Thracians weren’t — as far as we know, which isn’t very far, yet — barbarians. In fact, considering the way other cultures left their mark on the “Thracians,” and considering the cross-pollination of cultures, customs and artforms that grew and mingled within the territory — “Trace” might be a better name for Thrace. In the end, what I took away from “Ancient Thrace and the Classical World” was an ever-strengthening belief that the word “barbarian” and its feral companion, “savage,” need to be cast among the archaisms in the Oxford English Dictionary — and every other dictionary in every other language — until their usage is itself deemed “barbaric” and “othered” into anathema and oblivion.

Winners write the histories, but that doesn’t mean those histories are history.

The Getty Villa is at 17985 Pacific Coast Highway. For information, 310-440-7300 or www.getty.edu.