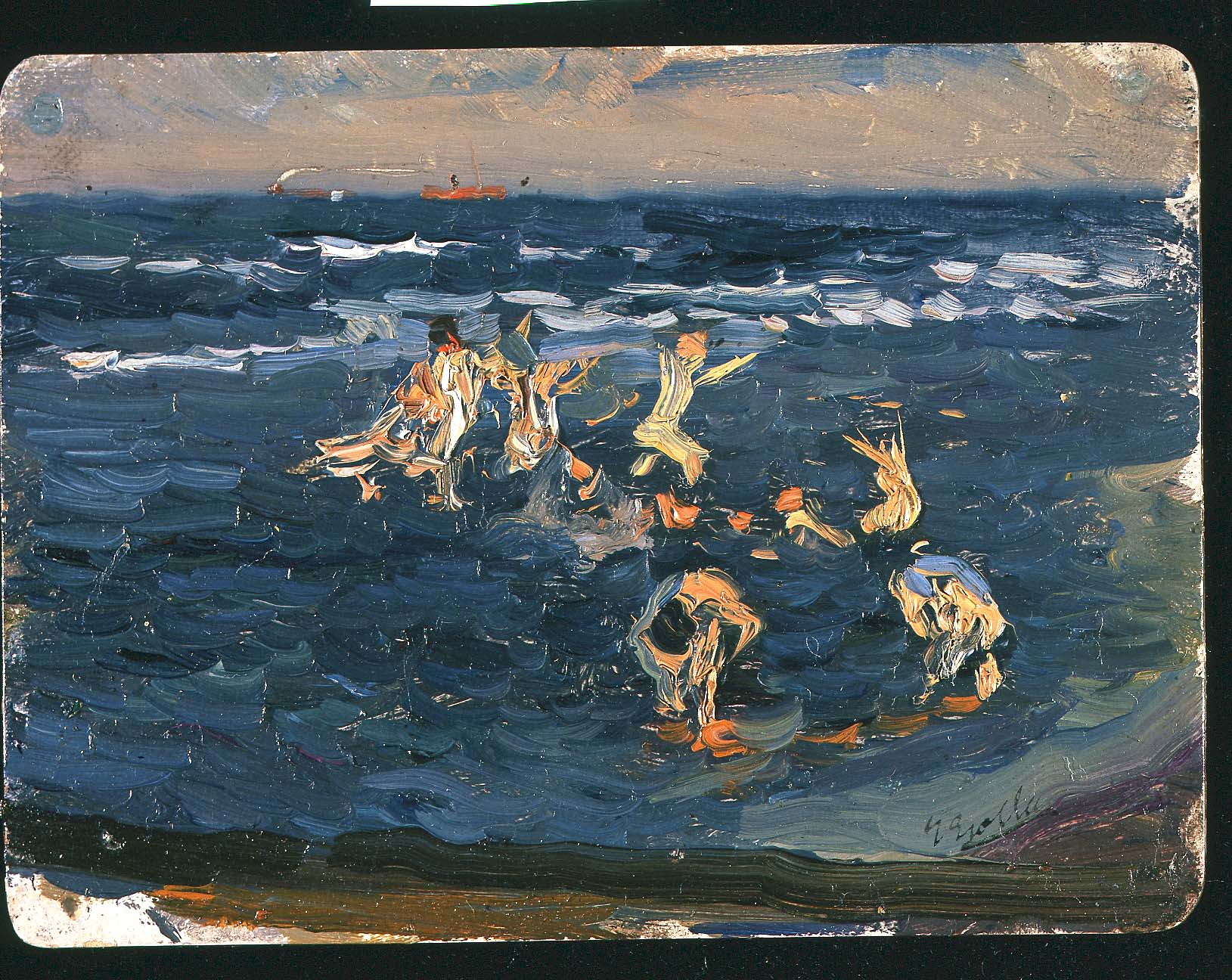

“Sailboats on Beach” by Teodoro Andreu, 1926, oil on panel, 12-11/16 by 16½ inches. Courtesy of The Hispanic Society of America, New York City.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

WEST PALM BEACH, FLA. — He’s the most famous Spanish artist Americans have never heard of — but to be honest that’s entirely our own fault. Once upon a time we couldn’t get enough of Joaquín Sorolla y Batista (1863-1923), known as Spain’s “painter of light,” who took Gilded Age America by storm in the early Twentieth Century. Working closely with the Hispanic Society Museum & Library (HSMC) as it completes renovations to its upper Manhattan facility, the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach presents “Sorolla and the Sea,” on view through March 16, 2025.

The Hispanic Society of America, as it was first known, was founded by scholar and philanthropist Archer M. Huntington in 1904, just six years after the end of the Spanish-American War. The study of Hispanic culture was Huntington’s life work, explains the Norton’s chief curatorial operations and research officer, Rachel Gustafson. “He was very much this visionary where he didn’t want the enemy to be misunderstood, so he took this grand effort to open this collection so people understood the people of Spain.”

One of the society’s boldest early efforts, in 1909, was a solo exhibition of the work of Joaquín Sorolla, by then a much-celebrated painter in Europe who exhibited (and won top awards) alongside the likes of John Singer Sargent, James McNeill Whistler and Gustav Klimt. The show drew 160,000 people to Washington Heights, an unmitigated triumph even by today’s museum attendance standards, and reaped Sorolla the equivalent today of about $5 million in sales of paintings. It also led directly to important portrait commissions among well-heeled Americans — including, also in 1909, a portrait of then-President William Howard Taft — and, eventually, a commission from Huntington himself for an ambitious mural cycle, completed in 1919, for a series of new galleries at the Hispanic Society.

“Boats on the Beach, Málaga” by José María López Mezquita, 1931, oil on canvas, 20-1/16 by 43-5/16 inches. Courtesy of The Hispanic Society of America, New York City.

Sorolla’s career effectively culminated in this blaze of glory. Notwithstanding his final years being marred by illness, there was no time when he struggled to hold on to relevance while being ignored by the press. How strange, then, that with the exception of some scholars of Nineteenth Century Spanish painting, presidential portraiture and fashion history (the HSMC murals are much admired in this respect), Sorolla should be largely forgotten while those with whom he shared an international stage have retained their place in the canon.

Rather than try to offer an explanation for this erasure, or to insist on Sorolla’s restoration to the history books, the present exhibition’s more approachable ambition, as conceived by HSMC’s director Guillaume Kientz, is largely to reintroduce the artist to US audiences — to give us the opportunity to experience anew what we found so irresistible more than a century ago, and to do that in a place where the legacy of Spain and Sorolla’s favorite subject of the sea are in the very air that museum visitors breathe.

It is worth pointing out that Sorolla’s visions of the sea are not wholly new to the Norton’s visitors. When Ghislain d’Humieres took the helm as director at the Norton four years ago, one of his major initiatives was to take on the long-term loan of a single monumental Sorolla work that had no easy display or storage solutions at the HSMC as it was beginning its renovation project.

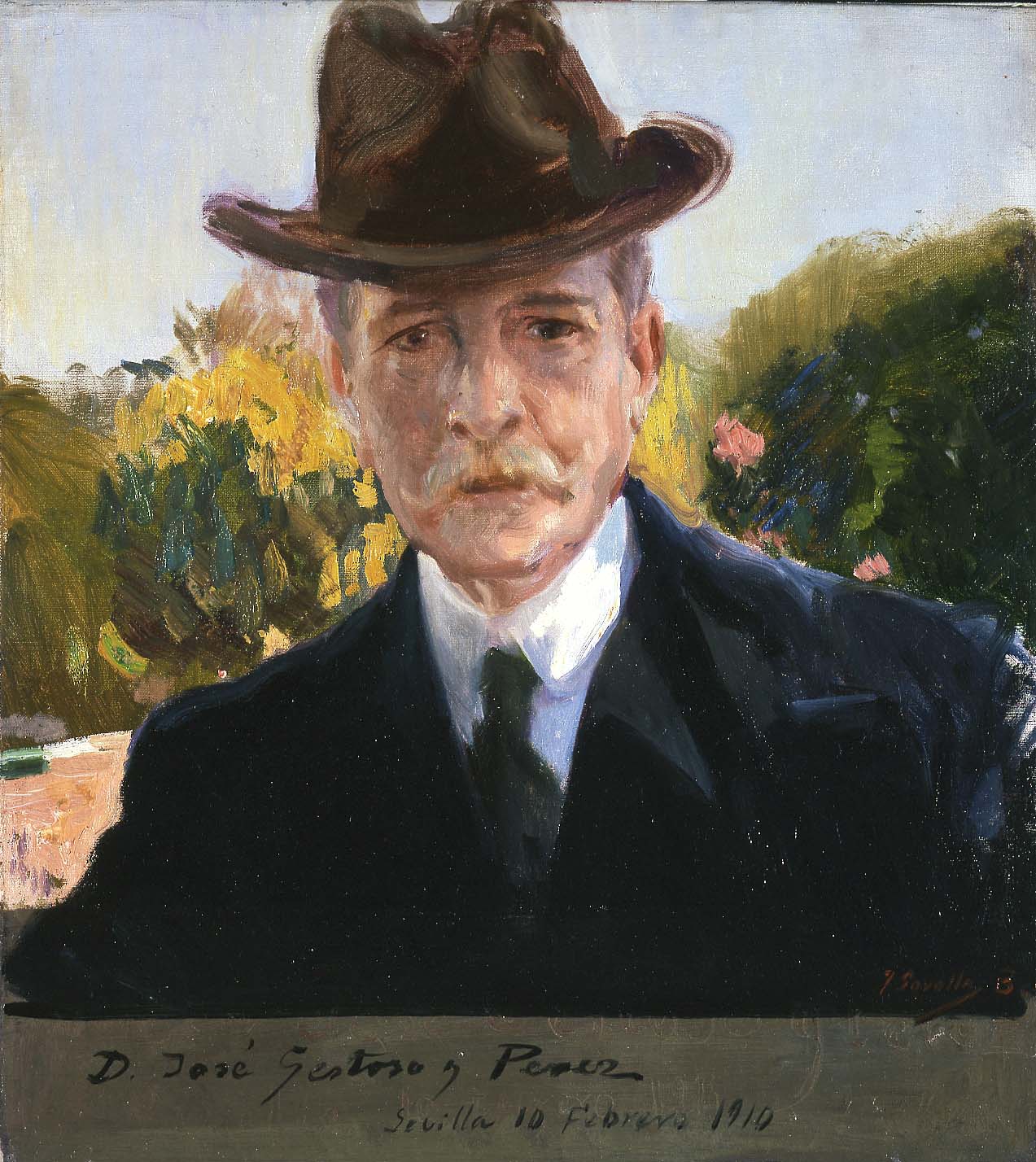

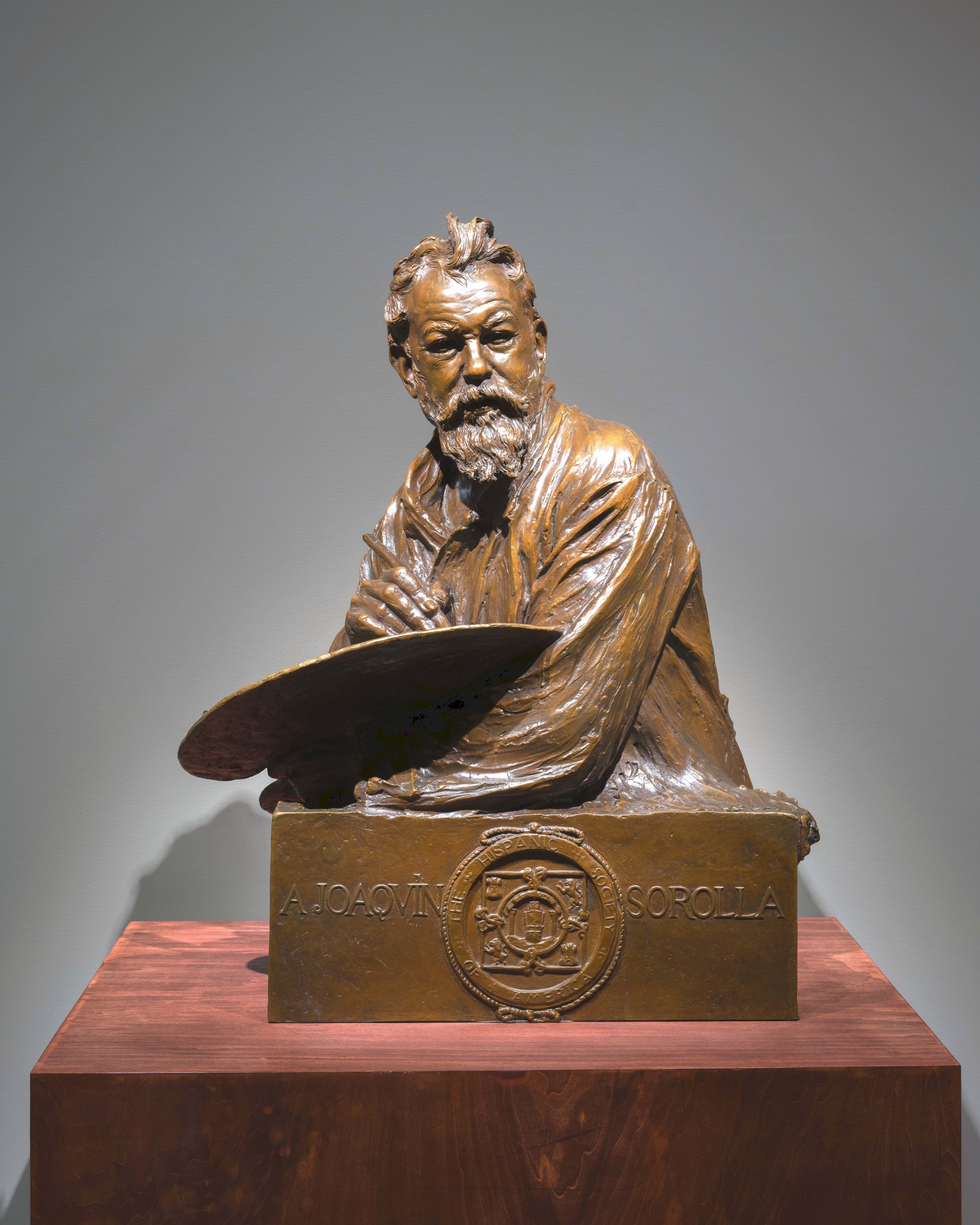

“Bust of Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida,” Bastida” by Mariano Benlliure y Gil, 1932, bronze, 36¼ inches tall. On loan from The Hispanic Society of America, New York City.

“That work was so large that it couldn’t fit into the gallery,” recalls Gustafson. “We re-stretched it in the room and then assembled the frame around it.” Fully 9½ feet tall by 14½ feet wide, with vibrant colors, life-size figures and a billowing sail that seems to breach the bounds of the canvas, “Beaching the Boat (Afternoon Light)” has since become a visitor favorite, making a Sorolla exhibition focusing on the sea an obvious next step.

The works on view are chosen to delight the eye, each on its own terms. The show is divided into five sections representing broad themes that stretch from lessons learned during Sorolla’s early training in Valencia to his magnum opus in New York. In the “Life and Work” section are portraits of family, friends and fellow artists that call on the revered Spanish tradition of realism in which Sorolla was schooled. Sorolla’s portrait of his wife, apparently seated on a balcony — her white skirt and elegant forearm struck by cool sunlight while the rest of her is in shadow — is a masterclass in chiaroscuro, clearly conceptualized during hours spent studying paintings by Velázquez and Caravaggio at the Prado (the Sorolla family relocated from Valencia to Madrid in 1890).

Part of the story the exhibition tells is the transformation in Sorolla’s technique and subject matter as he moved from his local artistic community to an international one. Gustafson says the shift is most apparent in the transition from this introductory section to the next, titled “Fishermen’s Life,” where the massive “Beaching the Boat” anchors the gallery. Sorolla was trained in the great tradition of history painting, but here he experiments with “the idea that you can paint these scenes that are heroic, and yet they’re not presenting some wartime victory; they’re presenting poor fishermen pulling in boats with their oxen — and it’s presented in this heroic sense and scale and treatment.” The freshness and spontaneity of Sorolla’s palette and brushwork are also evidence of his preferred en plein-air approach, aided by the invention of the portable paint tube. Throughout the exhibition, Gustafson has incorporated numerous archival photographs of Sorolla “painting giant canvases right there on the seaside,” a practice taken up by later Spanish painters like Teodoro Andreu and José María López Mezquita, also included in this section.

“Beaching the Boat (Afternoon Light)” by Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida, 1903, oil on canvas, 117-7/16 by 173-7/16 inches. On loan from the Hispanic Society of America, New York City.

The ocean shore is a locus for Sorolla’s interest in working people and the beauty of the everyday, but it was also a place where he saw a coming together of different kinds of people. Here are the colorful rhythms of the boats and their sails, the fishermen and their oxen, but here too are the families splashing together among the shallows — sometimes even in the same picture, as in “Beach of Valencia by Morning Light” — or the elegant young woman emerging from the waves like Venus stepping from her scallop shell as a devotee stands ready to robe her in white.

Sorolla’s numerous compositions of naked or near-naked children lying in the sand as the waves and sunshine wash over them (“Sea Idyll,” for one) are particularly poignant. It’s simple enough to see these as what they are — probably fairly accurate transcriptions of normal beach-day practices in turn-of-the-century Spain — but Sorolla almost certainly had something else in mind, too. In 1900, he won the Grand Prix at the Exposition Universelle in Paris for “Sad Inheritance” (not included in the Norton’s show), a challenging painting that shows a fully robed monk at the seashore surrounded by a group of disabled children, all nude, some of whom use crutches. This too, Gustafson says, was probably a real thing that Sorolla and others saw on the beach and not an invention — but his decision to paint it reinforces both the thread of social consciousness that runs through his work and his commitment to the idea of the beach as a “democratic space” that is for everyone, just as they are.

The section titled “En Plein Air” brings together a group of paintings that best illustrate Sorolla’s lively, spontaneous style when painting out-of-doors. A highlight here is his 1911 portrait of artist and businessman Louis Comfort Tiffany, made during a visit to Tiffany’s Long Island estate. Tiffany’s pose — seated outdoors in front of an easel, palette in hand — shows a kinship between the two artists, echoed in a posthumous bronze portrait bust of Sorolla in a similar attitude.

“Louis Comfort Tiffany” by Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida, 1911, oil on canvas, 59¼ by 88¾ inches. Courtesy of The Hispanic Society of America, New York City.

The field of flowers melding into a distant sea also suggests the composition of the stained-glass windows for which Tiffany’s studios were so renowned. Other portraits and sketches of handsome houses, lovingly rendered in sparkling sunshine, convey the deep delight of having friends with seaside homes and the gift of time to spend there, painting. This was during Sorolla’s victory lap, so to speak, of the United States, in the years just after his triumphant American debut at the Hispanic Society, when he was at the absolute top of his game and also at the top of everyone’s guest list.

If Sorolla’s social life slowed down at all after that, it was not because he had become less popular or his work was taken less seriously; in fact, quite the opposite. The same year that he painted Tiffany, he also signed a contract with Huntington at the Hispanic Society to create the mural cycle known as “Vision of Spain,” which gives its name to the last section of the show. The murals themselves are permanently installed in New York and cannot travel, but the HSMC has lent several large, colorful preliminary studies.

“You can’t really talk about Sorolla without talking about ‘Vision of Spain’ because it was such an important manifesto that he created,” says Gustafson, adding that “Spain as a peninsula is very much at play” throughout the series. “[The sea] is something that you see lingering in the background in many of these panels, and it’s even front and center in some.” It is a little difficult to tell what is happening in some of the studies on view (representing the Basque Provinces, Navarre, Aragon and Castille); they do not map directly onto the finished murals, which were revised and edited down over nearly a decade of constant work, much of it done on location in Spain. But here are the working men with their oxen, and here are mountains descending into blue sea, and here are bright blankets and fluttering scarves and crisp white shirtsleeves, with Sorolla’s vivid colors and fluid brushwork capturing it all.

“Sketch for the Provinces of Spain. Basque Provinces, Navarre, and Aragon” by Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida, 1911-1919, gouache on paper, 41¾ by 43-5/16 inches. Courtesy of The Hispanic Society of America, New York City.

“Vision of Spain” is “very much tied to ritual and culture,” Gustafson says, observing that Sorolla’s primary interest was in showing the multiplicity of traditions among the different regions of Spain. His attention to local costume is part of the reason that the mural cycle continues to be of interest to fashion historians today. “It’s like, ‘Look at this beautiful cacophony of color and wardrobe and ritual that I’m able to capture in showing all of these regions together in one space,’” Gustafson says, calling up some of the same language she used to describe the beach as a kind of democratic space where different kinds of people come together.

So, all things come back to the sea: from the Mediterranean city where Sorolla was born and lived for so many years, to the shores of Long Island where his paintings beguiled a generation of robber barons, to West Palm Beach, where a new generation of Americans can appreciate them again today.

The Norton Museum of Art is at 1450 South Dixie Highway. For information, 561-832-5196 or www.norton.org.