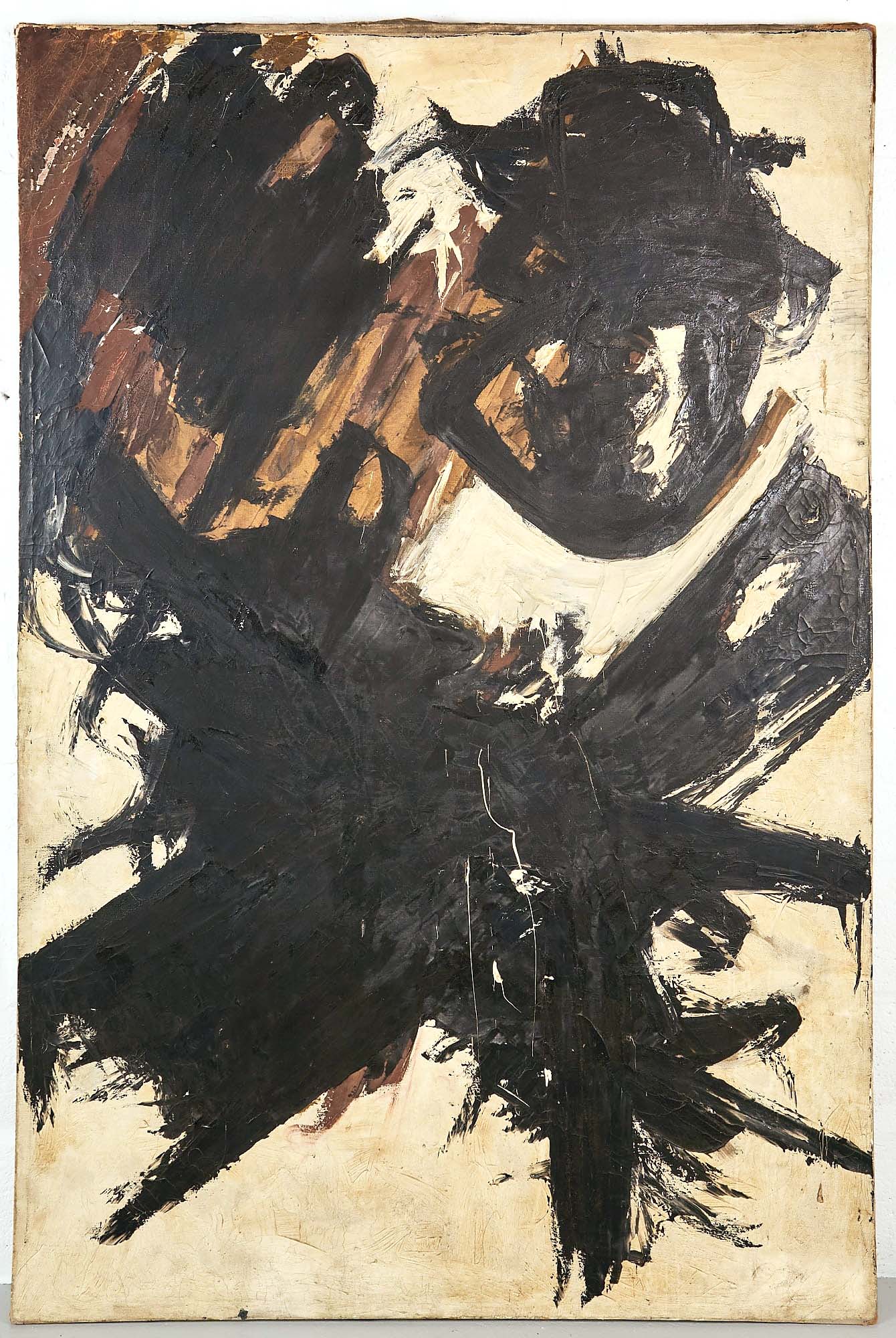

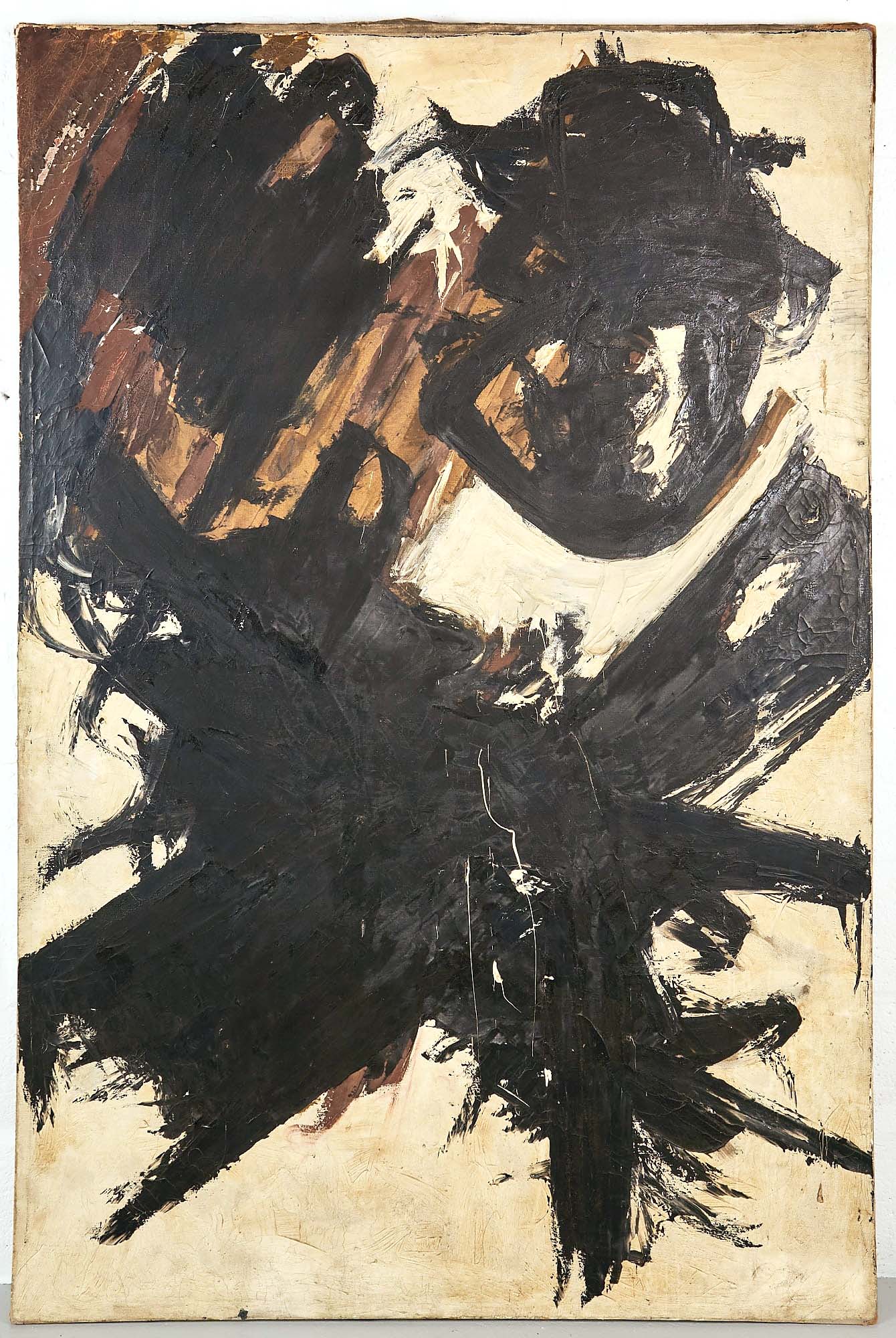

This abstract oil by Harlem Renaissance painter Edward Clark earned $55,800 and was the highest price of the three-day sale.

Review & Onsite Photos by Rick Russack

AMESBURY, MASS. — John McInnis Auctioneers chose to sell 950 lots over three days, January 3-5. There were distinct differences in the types of merchandise offered each day and this division made sense. Day one was fine art, day two was Americana from various estates and day three included fine Asian and Continental decorative arts. Some of the results were a pleasant surprise, with final prices far exceeding estimates, though reflective of pre-sale bidder interest. Unusual at auctions these days, there were about 50 bidders in the gallery for the second day, as well as several bidders in the gallery for the other days. They were active bidders, succeeding with several lots.

The first day began with 60 works by American artist Carl Ivor Gilbert (1882-1959). Some were passed but most sold, with “Two Men in a Canoe,” an oil painting, bringing $3,720 — the highest price of the selection.

The highest price overall — $55,800 — was achieved on the first day by a large, 6-by-4-foot oil on canvas by Edward Clark (1926-2019). Clark was known later in life for his abstract paintings, of which this was one. The catalog description stated: “he was one of the early African American pioneers of abstract painting in the post-war era and he credits his early inspirations as being the paintings of Nicolas de Stael and the music of Miles Davis and Charlie Parker.” The catalog further stated, “his large canvases were placed on the floor and painted with a push broom.” The lot was purchased by Newburyport, Mass., dealer Peter Clarke. Another work by a Black artist, Richmond Barthé (1901-1989), brought the second highest price of the fine art selection, $13,640. It was bronze sculpture of a woman in a hooded tunic. Barthé was active during the Harlem Renaissance and many of his subjects, including the one in this sculpture, were Black. Examples of his work are in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution and have been displayed in exhibitions at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. A charming graphite portrait of a young girl by Lilian Westcott Hale (1880-1963), who spent most of her working life in Boston, sold for $12,400.

We can’t say whether $31,000 is a world record for a bullet hole, but if so, it was achieved by this section of weathered clapboard pierced by a shot fired by British troops on April 19, 1775.

Perhaps one item sold on the second day might be declared a world record, but it isn’t a simple object to price check. A Revolutionary War artifact, it was a cased segment of a piece of well-weathered clapboard with a large bullet-hole in the center. It bore a typeset label that read, “Clapboard from the Adams house in West Cambridge, attacked by the British on their return from Concord, April 19th, 1775. The house was taken down in July 1855.” (April 19, 1775, was the start of the Revolutionary War). The mahogany case was signed by Jared Sparks (1789-1866), a researcher and educator who collected and preserved documents of America’s Founding Fathers. He wrote biographies of Benjamin Franklin, George Washington and Gouverneur Morris and was president of Harvard from 1849 to 1853. Its selling price, $31,000, was far above the estimate, but how does one predict the price of item like this? It had once belonged to an unnamed antique dealer where it had sat on the owner’s desk “for decades,” according to gallery manager Dan Meader; it sold to a private collector in the Midwest.

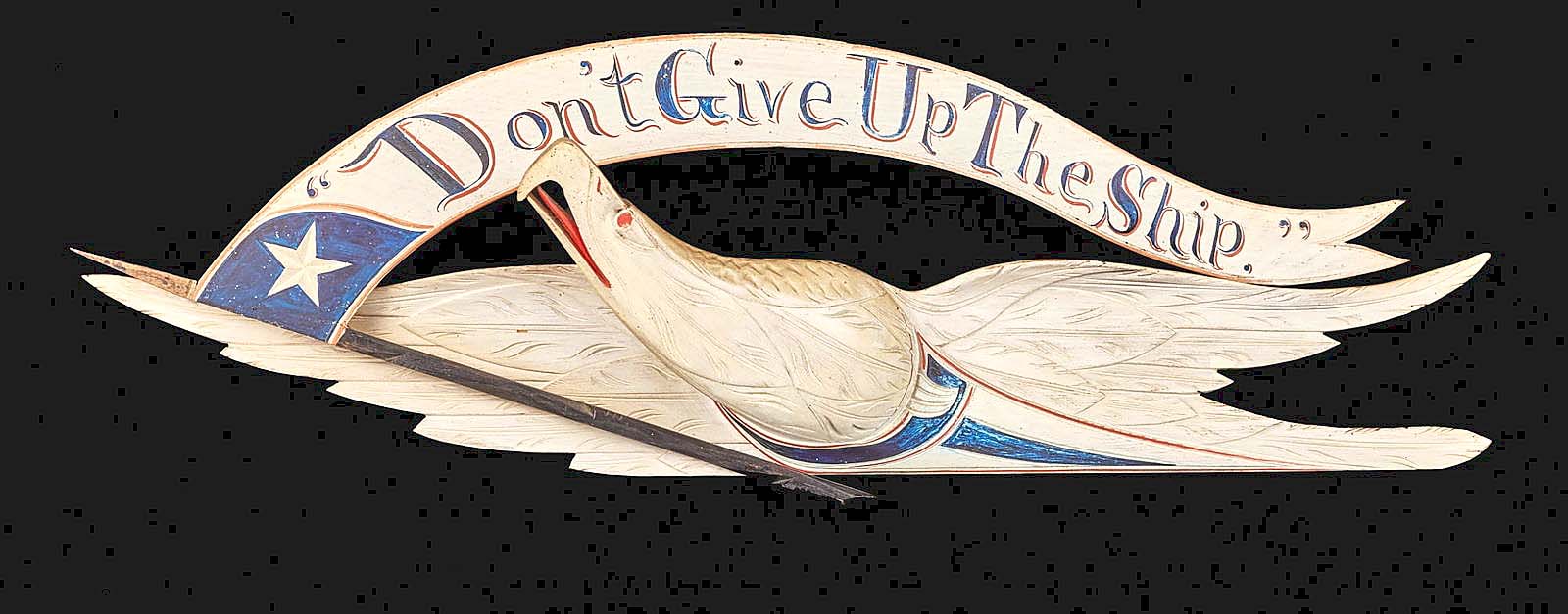

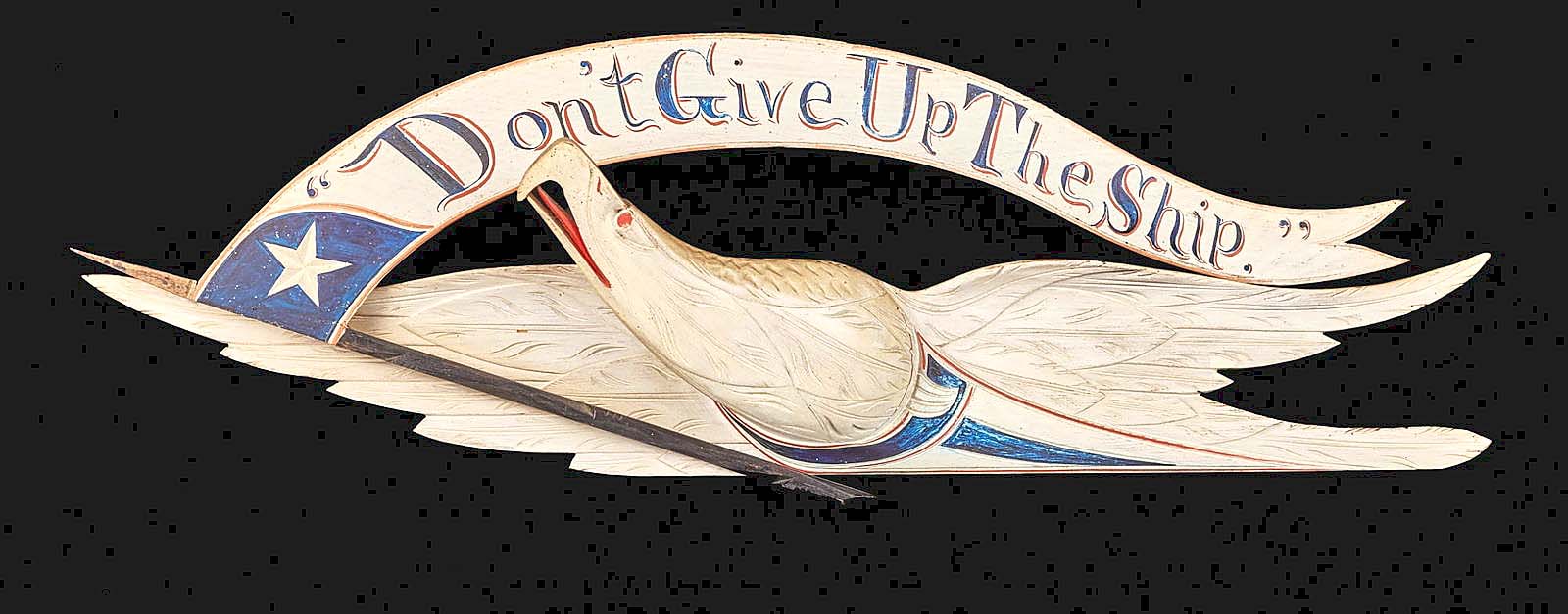

That price, the highest of the day, was tied by a 26-inch-long carved eagle plaque by John Haley Bellamy (1836-1914). Retaining its original white paint, the eagle held a carved, painted banner that was inscribed “Don’t Give Up The Ship.” The eagle had been in the family of the original purchaser since it was made and it sold to a collector in the gallery. When we talked to the purchaser, he said, “please don’t use my name. That could just make me a target for some thief,” which is an unfortunate sign of our times.

A pristine 26-inch-long Bellamy eagle, which had remained in the family of the original purchaser, sold for $31,000.

A strong offering of American clocks and furniture included a tall case clock made by Benjamin Swan (1792-1867), who worked in Augusta, Maine. The clock had an elaborate mahogany case, with turned columns, that was topped with fret-work and three brass finials. The cast iron face identified the maker, and it had a seconds dial and a rocking ship movement. With the original red wash finish, it sold for $17,360. There were several other tall case clocks, including examples by Nathaniel Monroe of Concord, Mass., James Perrigo of Wrentham, Mass., and Daniel Balch, who worked in Newburyport, Mass. There were also several banjo clocks and a large E. Howard mahogany wall clock that had belonged to the boxer, James L. Sullivan.

Expected to be the star of the furniture selection was a northern Essex County one-drawer blanket chest dated “1685.” It was decorated with applied, chip-carved moldings, half columns, spindles and bosses and the initials “H.T.” The chest had descended through seven generations of one family. Though it failed to sell, there was strong post-sale interest and a price was being negotiated at press time. A pair of Hepplewhite side chairs, possibly made by Samuel McIntyre (1757-1811), sold for $3,100. The pair had well-documented provenance to a Salem, Mass., home and were said to have been used by Nathaniel Hawthorne when he visited. Country furniture was led by an 1807 spirits chest on frame that also sold for $3,100. It had a well-weathered old blue surface, turned legs, stretchers and was lettered on the front in white, “ASB 1807.”

At $3,100, it was far from the most expensive item in the sale, but lovers of early country furniture had the chance to bid on an unusual item: a dated spirits case on a stand that featured a worn old blue surface, it stood 29 inches tall.

There was a group of about 60 weathervanes that had been made by the New England Weathervane Shop, in Hampton, N.H. The owners of the shop retired and consigned much of their remaining stock to McInnis. Some were original shop creations; all were handmade and many had been made from E.G. Washburne’s cast iron molds. The shop’s original creations were designed by Lee Webber, one of the owners, and hundreds of hours of labor were required for some, such as a fierce copper dragon with glass eyes, clad in copper scales, each of which had been hand cut and applied. This example required more than 280 hours to design and construct, and it sold for $2,480. The most sought-after vane was a unique copper peacock, nearly four feet tall, that required more than 400 hours of labor. It was modeled after a live peacock that lived at Webber’s home for many years. Also hotly contested was a 24-inch copper bicycle weathervane, which sold to an internet bidder for $3,100.

According to John McInnis, the take-away from the sale was quite simply that buyers “know what they want.” He said, “If it’s something special, there’ll be several people after it. And we’re seeing much more interest in Twentieth Century items and works by African Americans, whether it’s Twentieth Century or earlier. The market is strong but it’s changing. That’s good. This was a strong sale bringing in $840,000, with folks in the gallery actively bidding.”

Lovers of handmade cloth dolls have something to look forward to. Dan Meader shared with Antiques and The Arts Weekly that in February, McInnis will be selling close to 500 cloth dolls owned by Pat Hatch, who has been collecting and selling them for more than 40 years. She’s doing the cataloging for the collection.

For information, 978-388-0400 or www.mcinnisauctions.com.