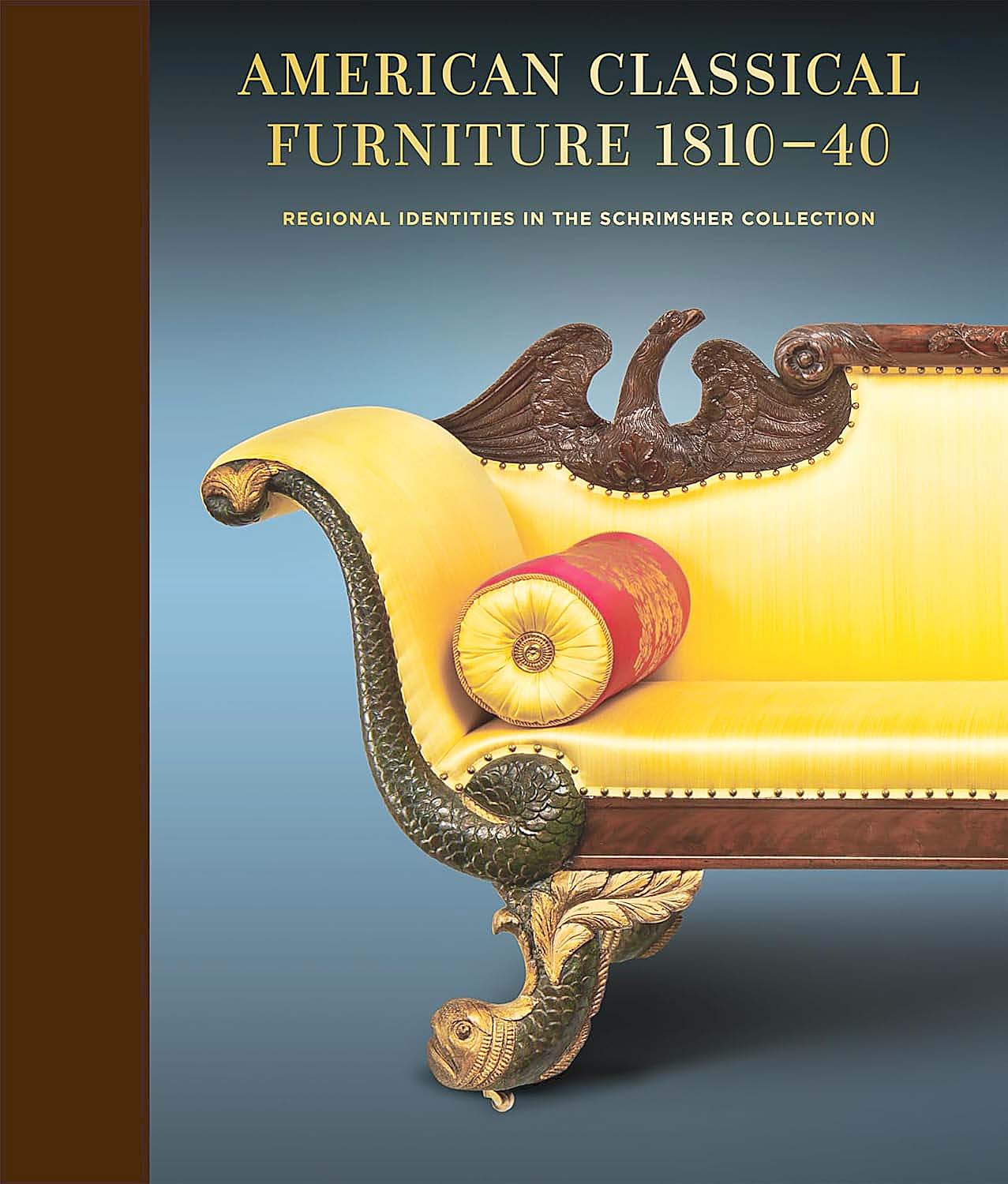

Classical carved and parcel gilt mahogany sofa, by an unknown maker, New York City, circa 1820. The presence of dolphin feet and stiles is a recognized characteristic of New York City-made Classical sofas that is not often paired with carved eagle crests.

By Madelia Hickman Ring

HUNTSVILLE, ALA. — James Orville Schrimsher (1926-2001) did not mince words when he voiced his opinion on Randall “Randy” and Kelly Schrimsher’s fledgling interest in Classical American furniture, “I wouldn’t give you a nickel to haul that to the dump.” Those dozen words did nothing to dampen the collectors’ interest in forming what has become one of the largest private collections of early Nineteenth Century American furniture and welcomes readers into what will certainly become a classic in the scholarship of the decorative arts: American Classical Furniture, 1810-40: Regional Identities in the Schrimsher Collection.

Figuratively speaking, the Classical aesthetic arose from the ashes of Herculaneum and Pompeii, which were buried in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 64 CE and excavated in 1738 and 1748, respectively. The world was captivated by the sculptural, bronze and ceramic treasures that were unearthed and which influenced both the Neoclassical and Classical styles. Denoted by linear and light forms that embraced delicate carving, inlay or paint, the Neoclassical aesthetic additionally employed the decorative elements of festoons, urns, bellflowers and lyres. The Classical style, the book’s introduction tells us, was, in comparison, defined by the “more robust archaeologically correct style of furniture that came into fashion in the US around 1810.”

The Schrimshers had initially started collecting Eighteenth Century American and English furniture, but their love of the Classical style began with the purchase of a historic Greek Revival home. “We acquired a few pieces of period furniture that fit the house’s aesthetic, and it was like a light bulb went off,” they told Antiques and The Arts Weekly. “Seeing the pieces in situ, within the architecture and scale of the house; everything just clicked. Until then, honestly, we weren’t even looking at objects from the Classical period. Suddenly, it all made sense, and we realized that the American Classical style was the direction we wanted to take.”

The Schrimsher Foundation’s new book: American Classical Furniture, 1810-40: Regional Identities in the Schrimsher Collection.

Existing research on furniture made in the United States between 1810 and 1840 has followed different methodologies, looking at individual cabinetmakers, analyzing a specific regional style or by examining the Classical aesthetic in broad sweeps and overviews.

The Schrimshers wanted their collection’s book to take a different approach than what had been followed previously. Building on prior regional studies, the couple forged a new path: a comparative analysis in which they “seek to illuminate the regional differences and similarities that define American Classical furniture and encourage further exploration of these themes.”

A few surprises emerged during the research and writing of the book, notably some reattributions, including identifying the maker of a New York stenciled secretary that the couple had acquired early on as Deming and Bulkley rather than Joseph Meeks as previously believed. A cabinetmaker in Pittsburgh was, in fact, the maker of some pieces initially thought to have been made in Philadelphia, and a worktable once alighted with Philadelphia was discovered to have actually been made in Baltimore. Conservation of a card table with an eagle base that was painted red, white and blue and discovered in a barn revealed the period finish underneath and the table’s original character.

Newly published by The Schrimsher Foundation, American Classical Furniture, 1810-40 incorporates essays by some of the leading scholars of regional Classical design, with a summary of form, motif and ornament. The catalog itself is comprised of 85 stellar pieces, lavishly illustrated with supplementary design sources or comparable examples, including some newly developed forms that had no precedent in the Eighteenth Century.

Pair of Classical rosewood and mahogany parcel gilt winged-caryatid card tables, attributed to Charles-Honoré Lannuier, New York City, 1815-19. The Schrimsher collection is the only collection — public or private — to boast winged-caryatid card tables attributed to both Lannuier and Phyfe, both of whom were inspired by French sources.

Wendy A. Cooper, a preeminent scholar of Classical design whose scholarship in the 1980s and 90s has been requisite reading for furniture enthusiasts, penned the book’s introduction with Kimberly E. Schrimsher — the couples’ daughter — that brings readers of every level up to speed. Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century architectural plates and prints — paired with English and European furniture design sources — clearly illustrate how the style was disseminated throughout Europe and England, finally arriving in the United States. Cooper and Schrimsher note that while each urban American center was influenced by the same pattern books and design sources, the four urban centers of Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York City and Boston “were resolutely distinct” that manifested in regional variations.

The book spotlights Boston and Salem, Mass., first. In his essay, “A Revolution of Style and Taste in Boston and Salem,” Clark Pearce noted that the English Regency variant that influenced all of the major American urban centers was “particularly strong in Boston and Salem,” though local cabinetmakers “filtered out most of the outlandish and avant-garde flourishes” to be more appealing to the local market. In practice, this is manifested in broad, flat planes of highly polished mahogany or rosewood, inlaid brass stringing and sinuous curves sparsely embellished with a single Classical motif. Balance and symmetry were paramount, in accord with the principles of classicism, as were monumental scale and minimal ornament.

Moving geographically southward, the book’s focus shifts to New York City. Peter Kenny noted several factors that contributed to the city being a furniture making metropolis: a vibrant cabinetmaking community, prosperous residents and a deep-water port that did not become icebound in winter created an environment that saw expanded trade in 1814, when British blockades along the eastern seaboard were lifted and, then in 1825, when the Erie Canal was built. Kenny describes the environment as “the bustling, competitive world of New York’s master cabinetmakers, who strove not only for financial success but also for recognition as proud contributors to the city’s commercial prosperity and as skilled artistic practitioners of their craft.”

Classical mahogany marble-top worktable, attributed to Duncan Phyfe, New York, 1810-20.

It was in such an environment that cabinetmakers like Duncan Phyfe (Scottish, 1770-1854) and Charle-Honoré Lannuier (1779-1819) worked, joined additionally by Barzilia Deming (1781-14854) & Erastus Bulkley (1798-1872), Joseph Meeks (1771-1868) and his sons; and Michael Allison.

In her essay on Philadelphia, established as the US capital while Washington, DC, was under construction on the Potomac, Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley notes the city was poised to become “the Athens of America,” replete with large public buildings, intellectual organizations and museums. French émigrés who came to the US to support the Continental Army, as well as high profile French nobleman, created a desire for French designs. Decorative motifs used spanned the range of cornucopia, lions and lion’s feet, dolphins, lyres, shells, Bacchanal garlands, radial fans, compass stars and intricate gilt stenciling. In addition to gilt bronze or ormolu mounts, Boulle work, marble slabs, specimen tops and painted stones were employed to great effect.

Boston, New York City and Philadelphia were similar in that by the time the Classical period came to fruition, they were all long-established cities with well-engrained cultural traditions and craft practices. Conversely, Baltimore did not have such a long history but alongside surging immigration following the Revolutionary War, Gregory R. Weidman identifies a “production of Classical furniture with an almost idiosyncratic style and aesthetic. Except for a small handful of forms and decorative elements closely related to similar pieces of Philadelphia manufacture, Baltimore for the most part went its own direction, with its own particular fashions, preferences and taste.”

Classical mahogany armchair, made for the White House by William King, Georgetown, Washington, DC, 1818.

The Schrimshers’ collection includes a few armchairs made in Washington, DC, which Matthew A. Thurlow discusses in a penultimate essay titled “Seats of Democracy in Washington, DC: Chairs for the Nation’s Capital.” The city had been invaded in August 1814 by British troops, which destroyed or significantly damaged by burning several important government buildings, including the White House and both the House and Senate chambers of the Capitol building, the Treasury building and the War department. Among the local cabinetmakers tapped to help replace the furniture were William King, Jr, (1771-1854) of Georgetown, who made an extensive set of seating furniture commissioned by President James Monroe in 1818; one of the chairs from that set is included.

The last essay in the book — by Christine Thomson and Wendy A. Cooper — explores the forms, motifs and ornaments that are part and parcel of the Classical aesthetic. In it, they discuss the economics of ornament, regional specialties, types and methods of ornamentation, metal mounts and hardware.

Two appendices, which precede the thorough bibliography and the index, enable quick visual comparisons between regional differences in various forms and illustrate several labels, inscriptions and stamps.

The Schrimshers are clear that they wanted the book to pose insights to future avenues of study.

“The collaboration with conservators also revealed new insights into the construction and material choices that had not been fully understood before,” noted Randy and Kelly. “They taught us so much about the science behind the restoration process and it changed how we view these objects. Just because a piece isn’t beautiful when you first see it doesn’t mean there isn’t merit. It was through these interactions with conservators and curators that we began to truly appreciate the artistry and history embedded in each piece.

“Our research, along with discoveries made in the field, has set the stage for further investigation into the complexities of American Classical furniture.”

For those readers who follow this field, we look forward to seeing what seeds it plants for the future.