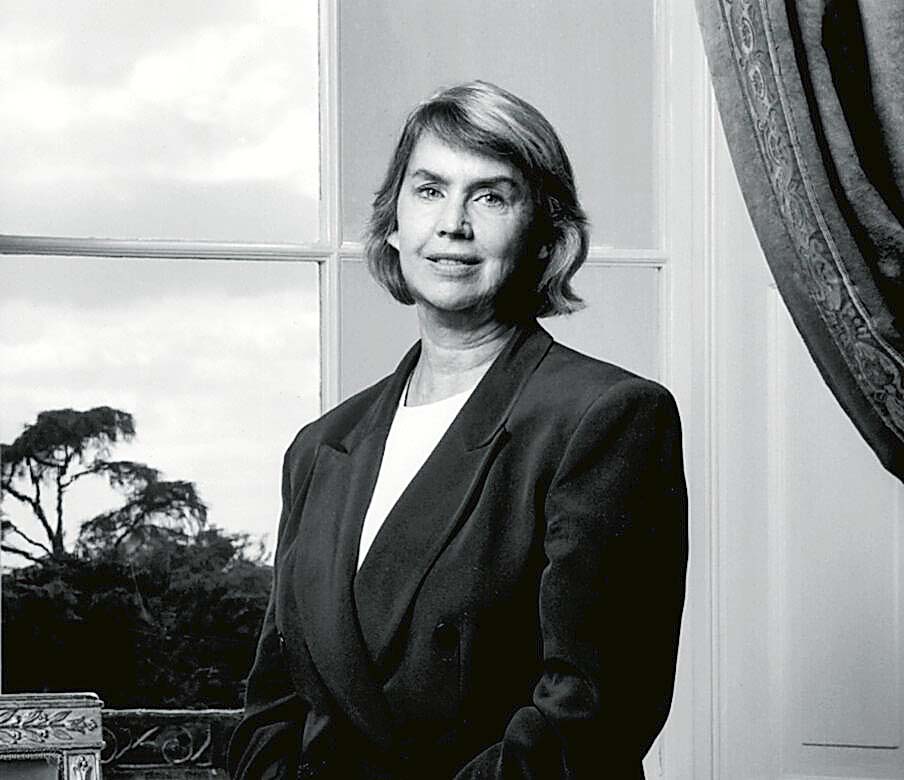

Betty C. Monkman served on the White House curatorial staff for 35 years, under eight presidents. Photo courtesy The White House Historical Association.

By Emily Langer

VIENNA, VA. — Betty C. Monkman, a former White House curator, who, during 35 years under eight presidents, was entrusted with the conservation and care of thousands of artistic and decorative treasures in the residence’s collection, died January 7 in Vienna, Va. She was 82.

She died at the home of a niece, Elizabeth Jackson-Pettine, who confirmed her death and said the cause was leukemia.

Monkman joined the fledgling White House curatorial staff in 1967, the year she turned 25. The role of curator had been created only six years earlier by first lady Jacqueline Kennedy and was officially established by an executive order of President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964.

Monkman was first hired as a registrar, tasked with keeping logs and inventories of a sprawling trove that had not yet been brought up to modern curatorial standards. She quickly earned the admiration of her colleagues with her knowledge, resourcefulness and respect for the traditions and history of the residence.

She was promoted to assistant curator in 1980 and became chief curator in 1997, a role she held until her retirement in 2002 and that encompassed preservation, conservation and interpretation.

“She very much cared for the collection and the White House itself, and that responsibility and enthusiasm was something that other people picked up on,” said Lydia Tederick, a colleague who later served as chief curator. “It was kind of catchy.”

With its vast holdings of artwork, furnishings, rugs, decorative pieces, textiles, light fixtures, china and flatware — items ranging from first lady Martha Washington’s sugar bowl to President Ronald Reagan’s rocking chair — the White House is a repository of centuries of American history.

Monkman’s knowledge made her a go-to guide for important guests, including Raisa Gorbachev, the wife of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, who toured the residence accompanied by first lady Nancy Reagan during a visit in 1987. Raisa Gorbachev did little to hide her dislike for the White House as a home.

“I would say that humanly speaking a human being would like to live in a regular home,” she remarked to a reporter. “This is a museum.”

Technically, she was correct. On Monkman’s watch, the White House passed the exacting standards of what was then the American Association of Museums to be accredited as a museum in 1988.

But the White House also serves as a private residence. After the Inauguration Day pandemonium, with the exit of one president and the arrival of another, Monkman and her staff guided the new first family through the collection, helping them furnish the rooms of their residence to their liking and make the house a home.

However storied its furnishing may be, the president, the first family and guests must use the White House as they would any other home. They sit on chairs and occasionally don’t place coasters beneath their drinks. At receptions, cookie crumbs inevitably end up on the fine rugs. Monkman and her colleagues gamely oversaw necessary repairs and refurbishments, ensuring that the treasures of the White House were well-preserved even as they added to the living grandeur of the home.

“We were kind of an all-purpose historical preservation office,” said William Allman, who succeeded Monkman as chief curator, adding that they were also “the connection between the first family and the collection.”

Betty Claire Monkman, one of four children, was born on August 24, 1942, in Bottineau, N.D., and grew up in nearby Souris. Her mother was a schoolteacher, and her father ran a cafe.

Monkman received a bachelor’s degree in history from the University of North Dakota in 1964 and initially followed her mother into education, taking a job as a teacher in Chicago.

Searching for other ways to indulge her love of history, she moved to Washington, DC, and worked for the DC Public Library before inquiring at the White House about job openings. There happened to be one for a registrar in the curator’s office.

Monkman continued her education in Washington, receiving a master’s degree in American civilization from George Washington University in 1980. Her survivors include a sister.

Monkman was the author of books including The White House: Its Historic Furnishings and First Families (2000), widely regarded as a definitive guide. With Allman, Tederick and another curatorial colleague, Melissa C. Naulin, she wrote Furnishing the White House: The Decorative Arts Collection (2023). She contributed regularly to the White House History Quarterly, the scholarly journal of the White House Historical Association.

Although her job was far removed from the politics of the White House, Monkman keenly felt the pressures of the place, such as when anti-Vietnam War protesters gathered outside the residence in Lafayette Square or when the Watergate affair closed in on President Richard M. Nixon. During Watergate, she said in an oral history for the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Foundation, “I would come home at night and my legs would just ache from tension, from being there.”

She also saw up close the toll that life in the White House took on its occupants. Many first families arrive with “this sense of hope and this sense of anticipation,” she said, but the “reality” of living in the White House, and of their lost privacy, soon sinks in. As curator, she saw it as her duty to respect both the private life of the president and his family, as well as the historical value of the objects that surrounded him.

“The White House personifies the presidency,” she once told The Washington Post. “If this place were only a museum, there wouldn’t be so much interest. It changes and evolves, and that’s what we are about as a nation.”