Needlework landscape showing a woman with a garland and a man picking pears, unidentified maker, Boston school, circa 1755, silk and wool on linen. Collection of Sharon and Jeffrey Lipton.

By Madelia Hickman Ring

DETROIT — There’s probably a pretty good chance that material culture enthusiasts are at least marginally familiar with samplers worked by girls as part of their education. While American needlework and samplers have been the focus of museum exhibitions in the past few decades, “Painted with Silk: The Art of Early American Embroidery” is the first such exhibition of its kind hosted by the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) and aims to bring this facet of American historical culture to an under-exposed audience.

The exhibition was curated by Kenneth John Myers, the museum’s Byron and Dorothy Gerson curator of American art and is comprised of 70 pieces, most of which were worked between 1735 and 1835. Only one predates that range and 11 are contemporary samplers by Elaine Reichek (American, b 1943). Nearly 60 samplers are from private collections — the majority belonging to Sharon and Dr Jeffrey Lipton (Michigan) and Suzanne “Suzy” and Michael Payne (New York), with a few from Anita and Louis Schwartz (Michigan) and two other collectors; four are from the museum’s own collection and seven are loaned from other institutions.

The lenders themselves told Antiques and The Arts Weekly they were impressed with how the exhibition was realized and its impact within the community.

“It’s a beautiful, spectacular exhibit, and I think it’s doing very well. I’m just delighted that people get to see this medium they don’t know much about. It will help the field of needlework and maybe spark an interest in collecting. Both Jeff and I are honored and humbled to be a part of this,” Sharon Lipton told us.

Needlework landscape by Elizabeth Townsend, dated 1793, probably Boston or Marblehead, Mass., silk on brown wool. Collection of Sharon and Jeffrey Lipton.

Michael and Suzy Payne stressed that these needleworks embodied the increased interest in women’s education following the American Revolution, a phenomenon that led, by the 1830s, to most of the white population in the Northeast being literate. “We are very interested in showing how this embroidery, besides being wonderful art, was also part of the increased interest in women’s education that occurred during the American Federal period. We have these unexpected, wonderful embroideries as evidence of the changes that occurred at this time.”

The exhibition relied heavily on prior scholarship, including Betty Ring’s (1923-2014) landmark 1993 publication Girlhood Embroidery: American Samplers and Pictorial Needlework, 1650-1850 (New York City: Knopf), as well as With Needle and Brush: Schoolgirl Embroidery from the Connecticut River Valley, 1740-1840 by Carol and Stephen Huber, Susan P. Schoelwer and Amy Kurtz Lansing (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 2011) and Connecticut Needlework: Women, Art and Family, 1740-1840 by Schoelwer (Hartford, Conn.: The Connecticut Historical Society, 2011).

Myers told Antiques and The Arts Weekly that the exhibition wanted to explore the subject in a way that hadn’t been done so previously. “Twenty or 30 years of scholarship on schoolgirl embroidery generally focused on identifying school traditions and the makers’ identities. Since the 1990s, there’s been a shift toward examining the cultural values that made needlework so significant for middle- and upper-class young women, as well as female educators who began to deemphasize embroidery after 1830 or so. ‘Painted with Silk’ draws on — and advances — recent academic studies that explore these themes.”

Installation view, “Painted with Silk: The Art of Early American Embroidery,” at the Detroit Institute of Art until June 15. Courtesy the Detroit Institute of Art.

For visitors unfamiliar with the genre, the show’s accompanying pamphlet outlines the various kinds of samplers crafted. Early band samplers — in which letters, numbers, images and quotations were organized into rows — were some of the earliest examples of the form and help initiate visitors to the medium. A 1755 example attributed to the Elizabeth Marsh School of Philadelphia and worked by a seven-year old Margaret Crukshank exemplified this and included two inscriptions that read “Today thy life to virtuous acts incline” and “Love the Lord and He will be a tender Father unto thee.”

Early samplers that taught basic stitches led to more complex needleworks that incorporated intricate techniques, decorative borders, sophisticated imagery and sometimes lengthy inscriptions. Often made by girls at schools that had the means and access to costly materials, such pictorial needleworks regularly illustrated scenes from literature and European art.

Religious samplers, featuring Biblical or Hebrew scenes, were commonly used to reinforce theological teachings to young women and examples in the show told the stories of Adam and Eve, Moses, David, Ruth and Naomi, to name a few. Myers observed that some of these pieces centered on stories of children being endangered and saved; he drew connections between that and the high mortality rate for young children. Exemplifying this is “The Finding of Moses,” sewn circa 1810 by an unidentified maker from Mrs Lydia Bull Royse’s School in Hartford, Conn.

Pictorial needlework titled “The Finding of Moses,” worked by an unidentified maker at Mrs Lydia Bull Royse’s School, Hartford, Conn., circa 1810. Collection of Suzanne and Michael Payne.

The issue of mortality is front and center in family memorials, of which several are included. “Sacred to the Memory of Isabella Clarke,” created by an unidentified member of the Clarke family of Richmond, Mass., was done in silk, ink and watercolor on silk around 1795 and exemplifies mourning samplers that often feature obelisks, urns, weeping willows and figures in black.

As part of their curriculum, schoolteachers — mostly unmarried women or widows from genteel families — recommended subjects or quotations and outlining designs on stretched fabrics for their students to embroider. In doing so, works by different students from the same school shared common compositional elements.

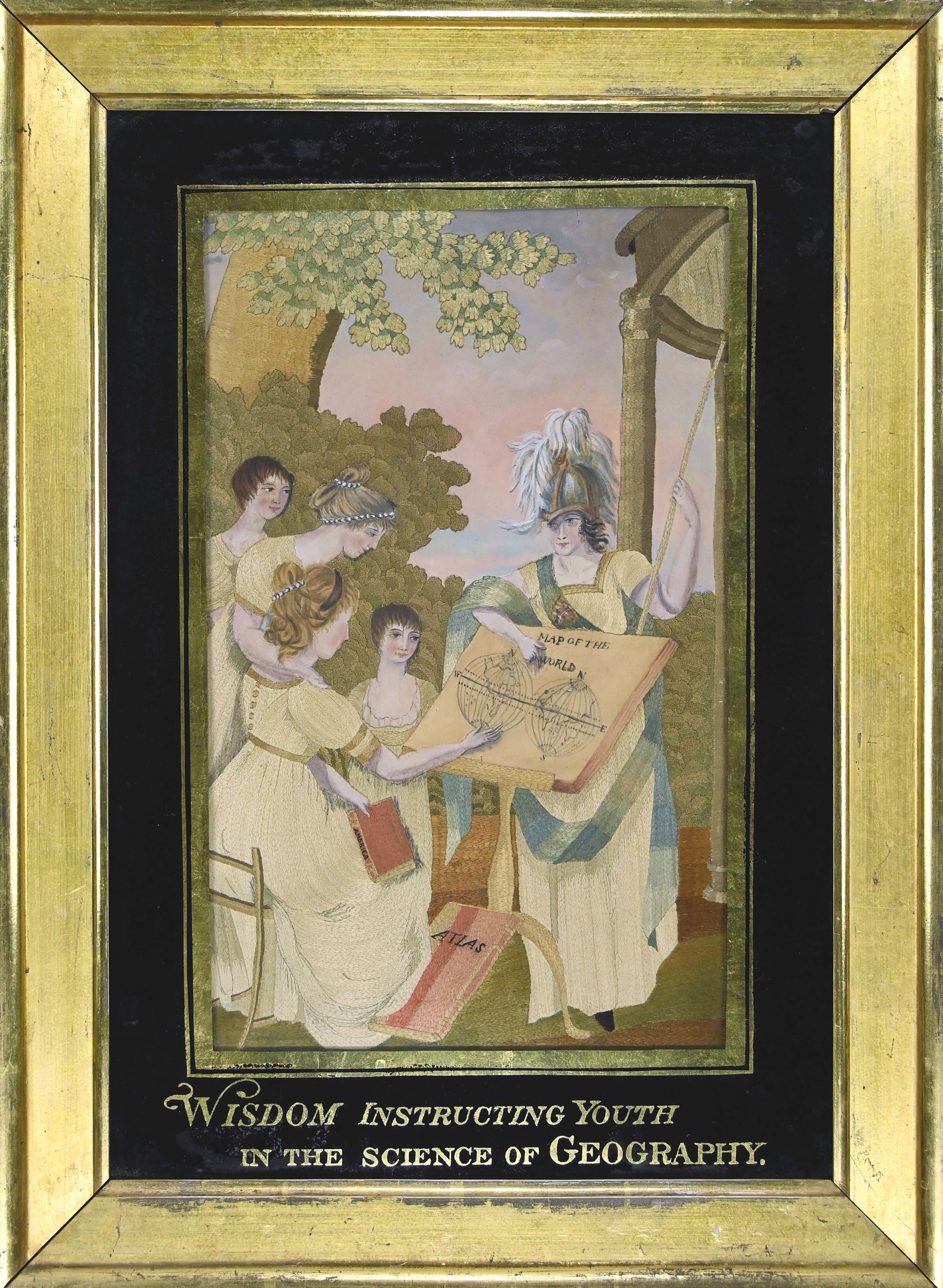

Virtue and other desirable attributes of young girls that would grow into womanhood and motherhood were frequently employed themes, too. Silk-on-silk embroideries by older girls might emphasize subjects that address the responsibilities of women as wives and mothers. “Wisdom Instructing Youth in the Science of Geography” exemplifies the most sophisticated of the latter. Copied after a 1799 English print source, it was worked around 1810 by an unidentified maker from Susanna Rowson’s Academy in Boston.

Pictorial needlework titled “Wisdom Instructing Youth in the Science of Geography,” worked by an unidentified maker, attributed to Susanna Rowson’s Academy, Boston or Boston area, Mass., circa 1810. Collection of Suzanne and Michael Payne.

Other themes are also addressed, one of which is “Home.” Samplers that feature large well-built homes on landscapes filled with flowers, trees, animals, birds and people. Included in this section is Sarah Eckstein’s 1818 sampler that was worked when she was 9 years old and depicts a house and yard. Lenders Louis and Anita Schwartz have an affinity for house samplers and their loaned examples all feature houses or buildings prominently.

Needleworks reflected a school’s literary or artistic curriculum. Jean-François Marmontel’s 1766 play, The Shepherdess of the Alps, echoes the plot of the biblical story of Ruth and provided the inspiration for Ann Susan Hancock’s (1807/08-1866) “The Shepherdess of the Alps,” worked circa 1820 in silk and watercolor on silk at the Charlestown Academy in Charlestown, Mass. A silk and watercolor on silk picture made at Susannah Rowson’s Academy in Boston by Dorothy Gardner is titled “Selim, or The Shepherd’s Moral” and is drawn from a 1788 hand-colored engraving by Francesco Bartolozzi (Italian, 1727-1815) after a painting by Angelika Kauffman (Swiss, 1741-1807).

The museum tackles the issue of race with a section on “Presence and Absence: Black People in Early American Embroideries.” Few Black girls were able to afford elite schools where needleworking was part of the curriculum or were not admitted at all. A few embroideries in the show include images of Black people or are connected to the lives of specific Black Americans. One of these, a watercolor, crewel, chenille thread and gold foil on silk picture, probably made at the Misses Pattens’ School in Hartford, Conn., by Ruth Green, includes a Black servant. The history of the Mortimer family, which made its fortune in Middletown, Conn., using enslaved Black people to manufacture rope, is explained alongside a sampler made by Martha Mortimer Starr in 1791, at the age of 14.

Sampler by Martha Mortimer Starr (1777-1848), about 14 years old, dated 1791, silk on linen. Collection of Sharon and Jeffrey Lipton.

The Paynes were particularly pleased with the museum’s attempts to engage the public and introduce the materials. “That they printed 10,000 copies of a 45-page exhibition catalog, which includes 14 of our examples, and then decided to give a copy, without charge, to everyone who visits the exhibition, is simply extraordinary. At the end of the exhibit, there’s an area for kids to play with the concept of making samplers, whether using magnetic pieces they can put together or using paper and crayons to make samplers using blank patterns. It’s really marvelous.”

“Painted with Silk: The Art of Early American Embroidery” is on view through June 15.

The Detroit Institute of Arts is at 5200 Woodward Avenue. For information, 313-833-7900 or www.dia.org.