Rob Hunter & Brandt Zipp on February 10, 2025, Michelle Erickson photo.

The antiques world likes nothing so much as a discovery, particularly one that upends longstanding scholarship. Three years after Brandt Zipp, partner at Crocker Farm auction house in Sparks, Md., discovered the true identity of African American stoneware potter Thomas Commeraw, he and ceramics scholar and dealer Rob Hunter have determined that some face jugs attributed to John Wesley were made, not by a white potter in Pennsylvania, but by an enslaved Black potter in South Carolina. The two have just presented their findings at the March 14-15 MESDA Southern Ceramics Forum but gave Antiques and The Arts Weekly a sneak peek behind this breakthrough research.

Can you give our readers some history on what was previously known about John Wesley? Why was he important?

BZ: I spent many years researching Thomas W. Commeraw, the first African American pottery owner, who worked in New York City in the late Eighteenth and early Nineteenth Centuries. I serendipitously discovered many years ago that he was not, as previously believed, yet another white potter of European descent, but a free Black potter and one of the most prominent African American craftsmen of his day. This research culminated in my book, Commeraw’s Stoneware, which was published in September 2022.

As part of that research, I realized that there were numerous other Black American potters who had never been documented, and I began working on them, as well. John Wesley was one of these potters. I had found him in the federal census as a potter working in Columbia, Penn., in the second half of the Nineteenth Century. He was Black and born in South Carolina. This was intriguing to me because a lot of scholarship has been done in recent years on the enslaved craftsmen of Edgefield District, S.C., the most famous being David Drake, commonly known as “Dave,” a figure who has become the most recognized of all period American potters. The traveling exhibition “Hear Me Now,” which began at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in September 2022, was one of the most high-profile American decorative arts shows of the last many years, and it was entirely focused on these South Carolina potters. A large portion of the exhibition was focused on the face jugs these specific potters were known for making.

Face vessel, attributed to John Wesley, Mecklenburg County, N.C., 1852-54, alkaline-glazed stoneware. William C. And Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation; Robert Hunter photo.

The only modern reference I’ve ever seen to John Wesley’s existence was a paper from 1946 that documented Lancaster County, Penn., potters; this paper seems to have assumed that he, like all other potters of that time and place, was white. In other words, until very recently, John Wesley was an extremely obscure footnote of a potter assumed to be one of many other white potters making redware in Lancaster County. I was very curious about what type of pottery he was making in Pennsylvania and how he got there, but before Rob contacted me, all I had was documentation of his existence.

What led you, Rob, to connect this research with Brandt and what he’d been working on?

RH: I have had a long-standing research interest in the history of Edgefield face vessels having edited several seminal articles for Ceramics in America. In addition, I have acquired numerous important examples for various private collections and museums.

During my research for a forthcoming article titled “About Face” in the 2024 Ceramics in America, I was reviewing the provenance of a redware face vessel in the Colonial Williamsburg collection. During the acquisition process in 1984, information had been provided to Colonial Williamsburg’s curators, that a similar face vessel had been recorded around 1940 and had been found in Southern Lancaster Country near Washington Borough. Incised deeply across the back of that example was “Willa | Frisby | Made by | John Westly” and on the bottom “1870.” That jug surfaced in 1993, in the sale of the collection of Robert R. and Joanne Dreibelbis, at Pennypacker’s Auctioneering and Appraisal Services.

BZ: As part of my Commeraw Project, I decided to publish online a list of newly discovered African American potters that I had systematically extracted from the Federal census. I felt it was important to make this internal research of mine as widely available as possible because it might help lead to new discoveries. I had found in my Commeraw study that too often the names of African American craftsmen and even historical figures were languishing in primary sources without anyone taking the time to bring them to light. I think part of this came from an outmoded mindset that Black craftsmen played no significant roles — or very few significant roles — in the development of their respective crafts. Because a lot of the foundational research in American decorative arts was performed decades ago by people who had this mindset, a lot of times modern scholars fall into the trap of believing that the relevant sources have already been mined and exhausted, when, in actuality, the exact opposite is true.

The Colonial Williamsburg jug is an extremely high-level example of an American ceramic face jug. During this time period, the bulk of surviving face jugs were made from stoneware; this is one of the finest redware ones known. (Redware is an easier pottery to make than stoneware; stoneware requires clay that is harder to come by and must be fired to a much higher temperature than redware). Apart from the Williamsburg jug, there are a few others clearly made by the same potter, and their origin has been the topic of much discussion over the last several years. One researcher, Phil Wingard — who wrote a Ceramics in America article on a famous South Carolina potter named Thomas Chandler — noticed that they were stylistically related to a single stoneware face jug signed by Chandler in Edgefield District, S.C. Because Chandler trained in Baltimore, a place with a large redware industry, he postulated that these redware face jugs were made there, and that was the prevalent opinion until now.

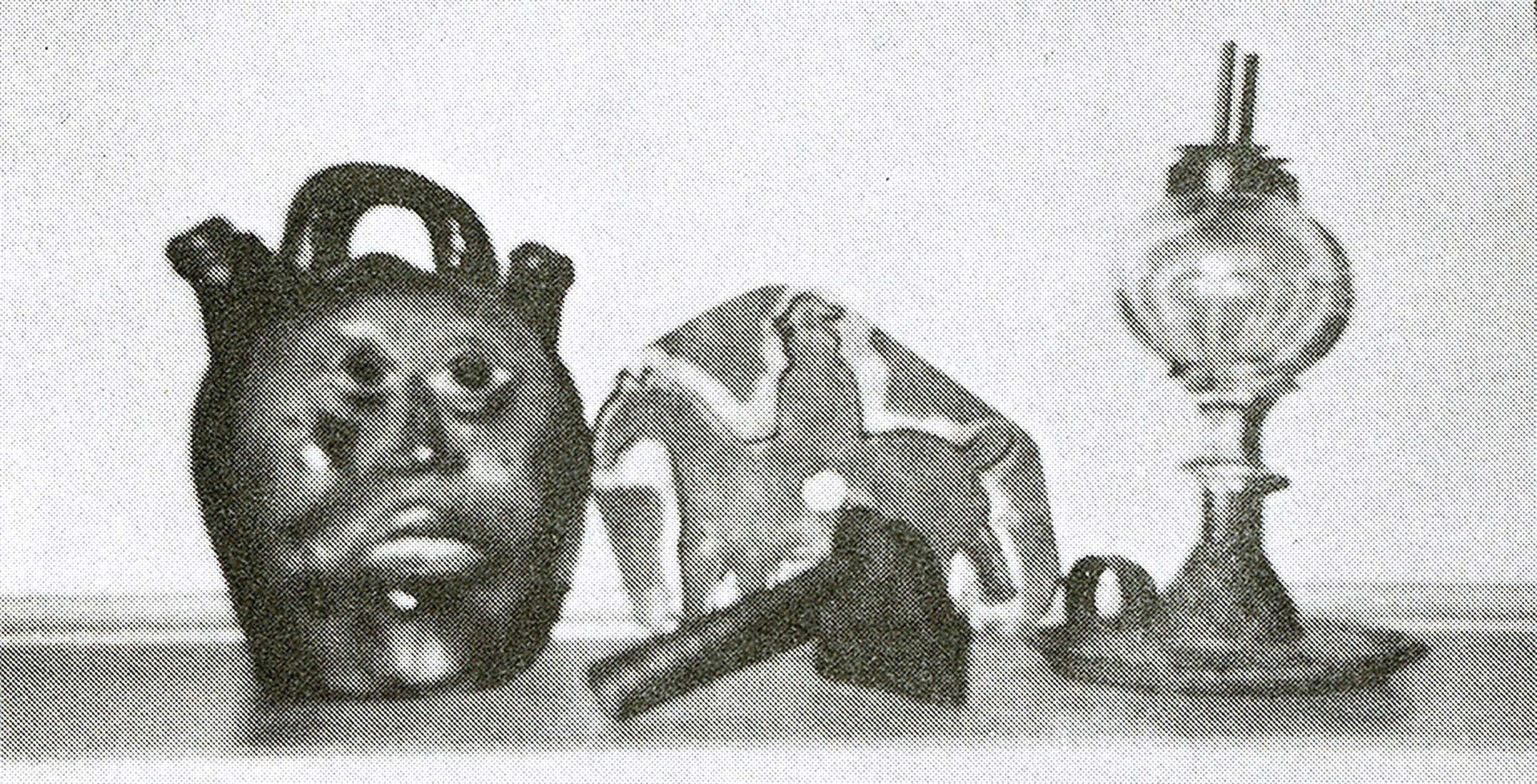

Catalog photograph scan showing, left, the face jug inscribed “Willa | Frisby | Made by | John Westly,” collection of Robert R. and Joanne Dreibelbis, sold by Pennypacker’s Auctioneering and Appraisal Services, May 17, 1993. Location presently unknown.

RH: Of course, I am familiar with Brandt’s groundbreaking research on Thomas Commeraw, however, during my search for a “John Westly” in the Lancaster area of Pennsylvania, I found his “African American Potters: 1850-1880 Federal Census Extract” (a running catalog of identified American Black potters) where a “John Wesley” was working in Columbia, Lancaster County, Penn., in 1880. Most important was the information that leaped off the screen, that Wesley was born in South Carolina in 1835. I immediately contacted Brandt to further discuss the ramifications of this discovery, and he excitedly began to explore further avenues of research.

BZ: When Rob contacted me in May 2023 to ask if I thought the John “Westley / Westly” of the Williamsburg jug could be the same John Wesley I had found in the census, my first thought was ‘this was probably too good to be true’ because there are a few things that are truly groundbreaking about this story.

Can you give us some sense of the scale of this discovery?

BZ: Right now, there is no greater focus of study in American decorative arts research than African American craftsmen. Similarly, I’m unaware of any specific type of object in American decorative arts more studied, talked about, debated and publicly intriguing as the ceramic face vessel. Yet, for all of this, we actually know very little about who made these objects — at least, the ones made by enslaved African Americans. The very nature of slavery tended to erase the artists’ identities, so we are left with a large number of face jugs made by different hands, yet very few actually attributable to specific artists.

From that perspective alone, being able to identify a handful of face jugs as the work of this specific formerly enslaved South Carolina craftsman is important. But from a general African American pottery perspective, shop ownership was extremely rare for Black potters. Thomas Commeraw was the first African American pottery owner, and he left the United States in 1820. I cannot think of another Black pottery owner in the North until John Wesley comes along, about 1870. He was the proprietor of his pottery in a place that is considered by many to be the birthplace of the Underground Railroad, a place he chose to settle in the wake of either escaping slavery or gaining his freedom legally. Just having this much biographical data about Wesley sets him apart from other African American face jug makers. The origin, use and meaning of American face jugs has been heavily debated in recent years and Wesley’s story is the first one that shows one of these Black craftsmen consciously transplanting the form in another location, clearly choosing it as a marketable ware in an area not known at all for face jug production.

After Rob contacted me, he and I both really dug into the historical record to try to flesh out Wesley’s life, in part to answer the question, ‘Did the John Wesley of Columbia, Penn., make the Williamsburg face jug?’ In the end, I was able to determine that the name on the jug — “Willa Frisby” — had to have been the “Aquilla Frisby” with whom Wesley served for at least several years as a trustee of the local Mount Zion African Methodist Episcopal Church, a congregation still in existence today.

Face vessel, attributed to John Wesley, Columbia, Penn., circa 1870, lead-glazed earthenware. William C. And Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation; Robert Hunter photo.

Does it open doors to further scholarship and, if so, what might that look like?

BZ: I really feel strongly that a next step in this field is going to be the identification of the artists who made these face jugs. They are truly steeped in mystery in multiple ways, but I think we can peel some of that mystery away by figuring out who made them. More importantly, I also feel strongly that there is nothing more noble in this line of research than being able to give these artists their identity back. Throughout my Commeraw Project, the thing that really drove me was the strong desire to give this person his life story back. And I feel the same way about these potters. As I said, slavery and even inherent bias in the historical record has at times almost entirely erased the legacies of many of these craftsmen. We are now able to give John Wesley his legacy back, and I’m incredibly hopeful that we can start doing this with others. I’m already starting to see other fruit for forgotten African American potters that I was able to identify through the Commeraw Project and it’s incredibly gratifying.

As for John Wesley specifically, any time we are able to publicize a specific craftsman like this, it absolutely opens doors for new objects to surface and for more information to come to light. I’m hopeful that that happens for him, and that we’re able to add to his body of work, perhaps identify some of his more utilitarian pottery, and maybe even find more signed examples. It will be exciting to start to see new objects attributed to him, to see his name start to appear on museum labels. He’s going to be talked about a lot in the coming years, and it will be very gratifying to see that happen.

—Madelia Hickman Ring