The Kohlmaier family, Kranzberg, Freising, Germany, 1907. Ruppert Kohmlaier Sr in infancy seated on Sophie Kohlmaier’s lap. Collection of Mr and Mrs Ruppert Kohlmaier Jr.

By Karla Klein Albertson

NEW ORLEANS, LA. – The ongoing exhibition in New Orleans about the history of the Kohlmaier family’s cabinetmaking workshop may change your approach to classic American furniture forms. Forget about buying someone else’s “antiques.” Daydream that you live in New York City in the early Nineteenth Century. You reject your parents’ old furniture, but you hear great things about this Scottish chap, Duncan Phyfe. So you go to the cabinetmaker, have a delightful chat about forms, materials and prices, and order exactly the table and chairs you desire.

Transfer that thrill to New Orleans, where from early in the Twentieth Century, a German family workshop has achieved acclaim for their beautiful furniture in traditional styles. You have seen entire museum wings filled with early American classics, and the Crescent City abounds in early homes and period settings waiting to be furnished. This cabinetmaker can supply the same sort of graceful forms, fine carving and brilliant inlay work, so off you go to the Kohlmaiers, enjoy talking it over and order exactly what you want.

“A Century on Harmony Street: The Kohlmaier Cabinetmakers of New Orleans” is an exhibition of approximately 30 of the Kohlmaier workshop’s creations. It is on view through September 30 in the third floor gallery of the historic Cabildo on Jackson Square, part of the Louisiana State Museum system. Once again, this furniture study and its accompanying scholarly catalog is the project of New Orleans researcher Cybele Gontar, who also organized the “Chasing the Butterfly Man” show covered in this publication in February 2020.

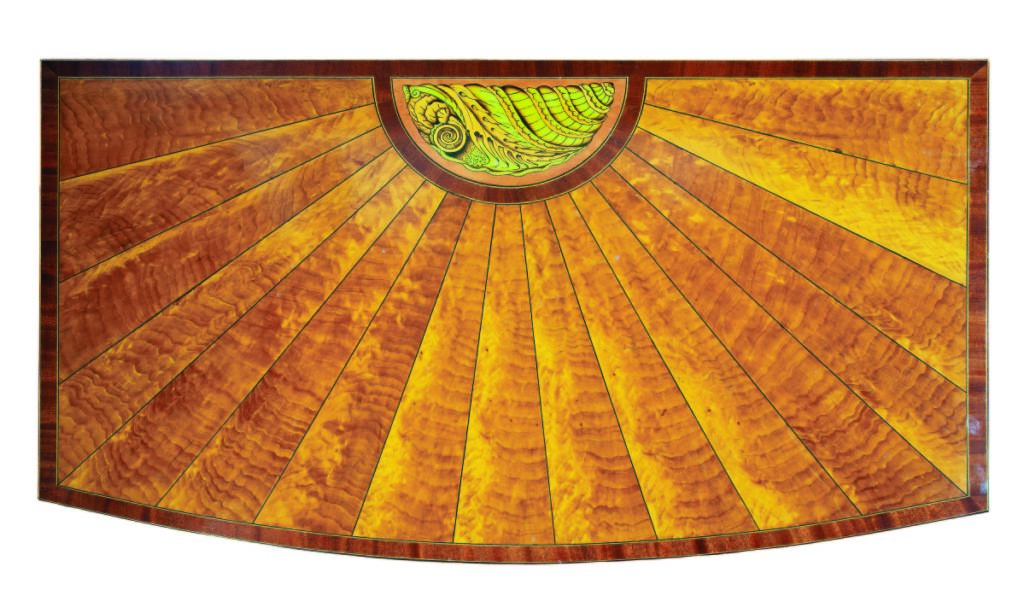

Detail, top of Sheraton-style chest of drawers, Kohlmaier and Kohlmaier, 2000, mahogany and cypress. —Jeff Strout photo

In an interview with Antiques and The Arts Weekly, Gontar recalled, “When I agreed to do it, I didn’t really fully understand the breadth of their accomplishments. Then I met one collector and another collector, and I started to realize the scope of what the father and son had accomplished. It was a testament to their abilities – their efficiency, their personable manner, their technical skill and their aesthetic judgment.”

“The museum was very amenable to this project, and we pulled it together very quickly. We had the first meeting in the summer of 2020. I worked constantly on the book until it went to print in September of 2021.” An important part of the research was meeting with Ruppert Kohlmaier Jr, now in his 80s. Gontar threw herself into the project, spending time in Kohlmaier’s workshop and listening to his wonderful stories of clients and commissions.

Her volume follows the family’s career in great detail, but the story of Ruppert Kohlmaier Sr echoes the journey of so many Europeans who crossed over to America around the turn of the century. Many fled poor economic conditions in the countries they left behind while bringing with them valuable skills in demand on this side of the Atlantic.

Federal-style chest of drawers, Kohlmaier and Kohlmaier, 1983, mahogany, cypress and brass. Collection of Richard and Suzanne Whann. —Terry Thibeau photo

Born in the Bavarian town of Kranzberg in 1905, Ruppert never wanted to be a farmer like his father. Instead – following a natural inclination – he began to study with cabinetmakers, where he took his first steps toward mastering the construction and inlay techniques for which he would become famous. The young man also did not want to be cold all the time.

Lured by colorful travel posters, he first emigrated to warm Brazil and studied further there. Then he moved on to New York, found it too chilly, and headed south, arriving in New Orleans in 1928. Since the Eighteenth Century, painters, silversmiths and craftsmen – French, Spanish, Italian and German – had been drawn to New Orleans because it was the marketplace where wealthy merchants and landowners would pay for their aesthetic skills.

After he arrived, Kohlmaier found work in his field, eventually joining the workshop at Feldman’s Antique Emporium, which sold fine reproduction furniture as well as antiques. There he made friends with other artisans, notably the carvers Vero Benvenuto Puccio (1910-1999) and Maurice Frederic Heullant (1983-1981) who would work with him throughout his career.

After several years, Kohlmaier left Feldman’s and set up his own enterprise, eventually settling by the late 1930s in his permanent location on Harmony Street in the historic Irish Channel area, between Magazine and Tchoupitoulas Streets. Meanwhile, Ruppert Sr had married Eulalie Martinez and they welcomed a daughter in 1930 and son Ruppert Jr in 1936, who has continued the business to the present day.

Freret-Winston Mantel, Kohlmaier and Kohlmaier, carving by Maurice Heullant after drawing by Douglass V. Freret, 1964, cypress. Collection of Margaret Winston.

—Terry Thibeau photo

The output of the workshop produced an elegant supply of what customers were demanding. Gontar notes, “The Colonial Revival was taking off like a rocket ship about the time Kohlmaier Sr arrived in New Orleans in 1928. That has a tremendous impact on the kind of furniture they made.”

As can be seen from the exhibits on display, these were not the reduced-scale forms we remember from our great-aunt’s parlor, but accurate recreations of English prototypes embellished with exquisite and restrained accents. Everything was available from a Hepplewhite-style chairs and Federal sideboards to inlaid card tables and elaborate bedsteads.

The shop also turned out fascinating regional forms such as the large wooden “punkah” fans hung over dining tables and the curving “campeachy” [sic] chairs, which introduced lounging comfort. Another New Orleans touch was the use of cypress wood inlay.

The earnest Americana collector will surely ask, why not buy some ancient used pieces – antiques – rather than ordering from the Kohlmaiers? Back to the beginning, why did people enjoy going to Mister Phyfe? The curator puts it well: “I would say, the bespoke nature of the pieces. You can get exactly what you want. It’s furniture that represents a certain moment in time. Collecting is such a subjective thing – but those interested in collecting New Orleans furniture or Anglo-American furniture, this would be the very traditional stuff to get.”

Parquetry box by Ruppert Kohlmaier Sr, 1929, walnut, satinwood, rosewood, cherry and birch. Collection of Mr and Mrs Ruppert Kohlmaier Jr. —Terry Thibeau photo

She continues, “In the New Orleans community, here are so many people who have invested in the Kohlmaiers and are total devotees. One collector would recommend another. I realized that the story is as much about the collectors and their relationship with the Kohlmaiers as about the furniture itself.”

Not surprisingly then, while Part One of the catalog recounts the history of the workshop, Part Two focuses on great family collections of furniture made to order by the Kohlmaiers. There the reader can view images of the furniture as it is lived with and enjoyed in a residential setting.

In the chapter on “The Whann Collection,” Richard Whann remembers when he visited the cabinetmaker’s shop with his father Robert “and my interest in and love for finely crafted furniture developed.” To see the finished product is one thing, to see the intricate process that went into a personal commission is another. The magnificent Chippendale-style bookcase with carved pediment, made for the family in 1972, appears opposite the title page of the catalog.

Parlor of the Gundlach Residence, New Orleans. —Terry Thibeau photo

At the end of the chapter, Whann offers this tribute, which gets to the heart of the matter: “I consider each of the Kohlmaiers to be an artist of the highest caliber. In my opinion, their knowledge of furniture history and styles, construction, and woods is superb…. We treasure our furniture made by the Kohlmaiers. Over the years, it has given more pleasure than I can say.”

The illustrated catalog, A Century on Harmony Street: The Kohlmaier Cabinetmakers of New Orleans, opens with a congratulatory letter to the cabinetmaker from Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards who mentions his enjoyment of the furnishings the firm has made for the mansion in Baton Rouge.

“A Century on Harmony Street: The Kohlmaier Cabinetmakers of New Orleans” is at the Cabildo, at 701 Chartres Street. For information, 504-568-6968, 800-568-6968 or www.louisianastatemuseum.org/museum/cabildo.

Editor’s Note: The exhibition catalog is available for purchase at https://www.thelmf.org/kohlmaier ($65) or https://www.octaviabooks.com/product/kohlmaier-cabinetmaker ($60).