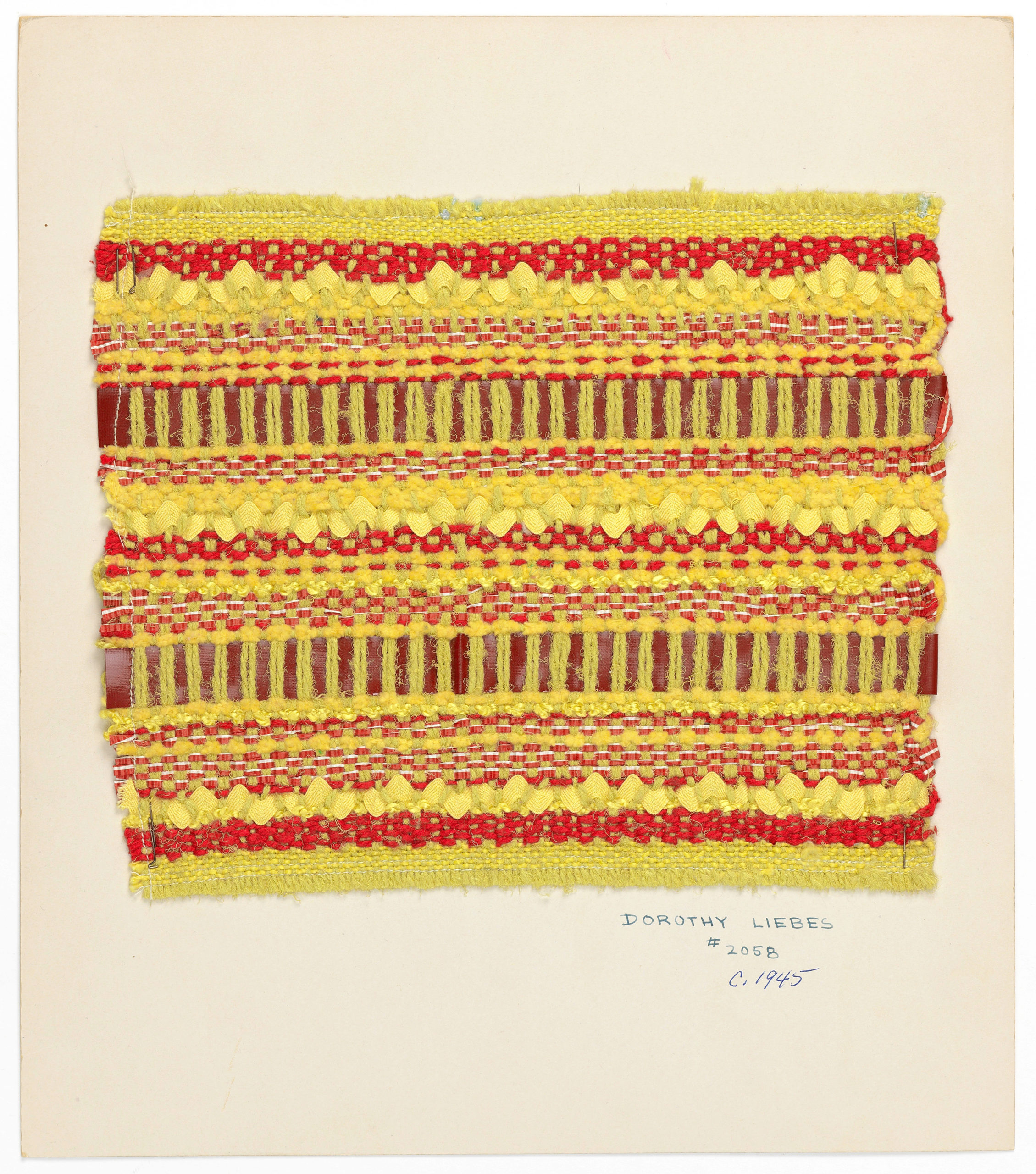

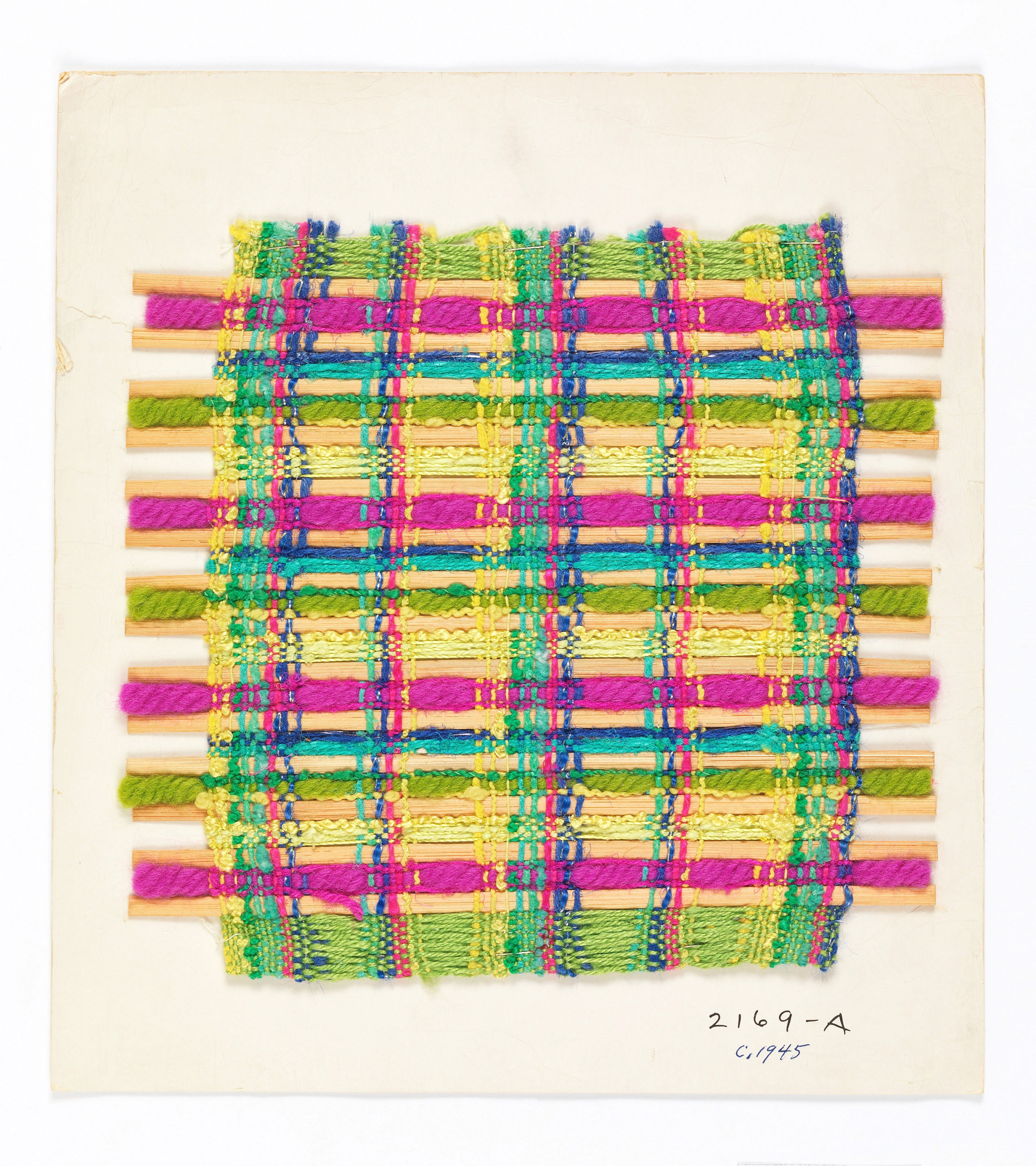

Sample card with hard materials interspersed with soft yarn as textural contrast. Gift of the Estate of Dorothy Liebes Morin. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.1972. Photo: Matt Flynn © Smithsonian Institution.

By Pat Hickman with Gail Hovey

NEW YORK CITY — Dorothy Liebes is one of the Twentieth Century’s most innovative and influential designers. She gained the spotlight as director of the Decorative Arts Pavilion at the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition in California. Her clients included Frank Lloyd Wright and the heiress and philanthropist Doris Duke. Her designs were installed and exhibited around the world, from the United Nations Delegate Dining Room in New York City to the 13th Triennale di Milano to the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Ansel Adams photographed her work. Vogue, House Beautiful and House & Garden featured her and celebrated her genius. Not only a star in the luxury market, she consulted for Sears Roebuck, Jantzen and Cole of California, designing for the mass market.

Yet, you may never have heard of her.

The Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York City, intends to change that with “A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes,” which opens at the museum on July 7. Interior design is a collaborative endeavor, involving both architects and designers. Yet the history of design has focused on the architect alone, usually a man. As a result, Dorothy Liebes has gone missing, despite the fact that in her lifetime she was better known than many of those with whom she worked. The digitization of her papers, made available in 2020, allowed the curators of this exhibition to spend the pandemic exploring a treasure trove of information. Co-curator Susan Brown thinks that the papers will “be informing research and exhibitions for years to come.”

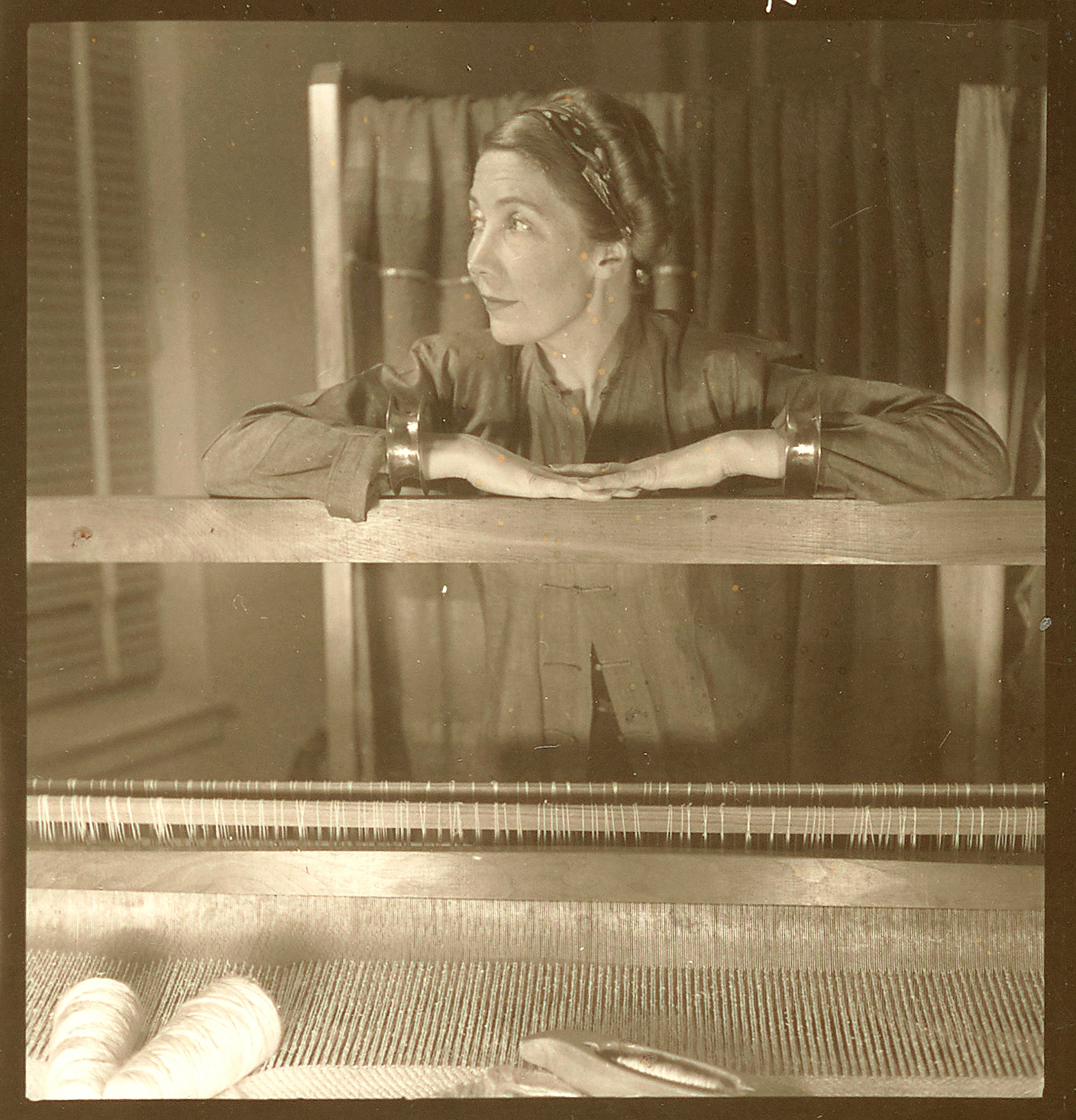

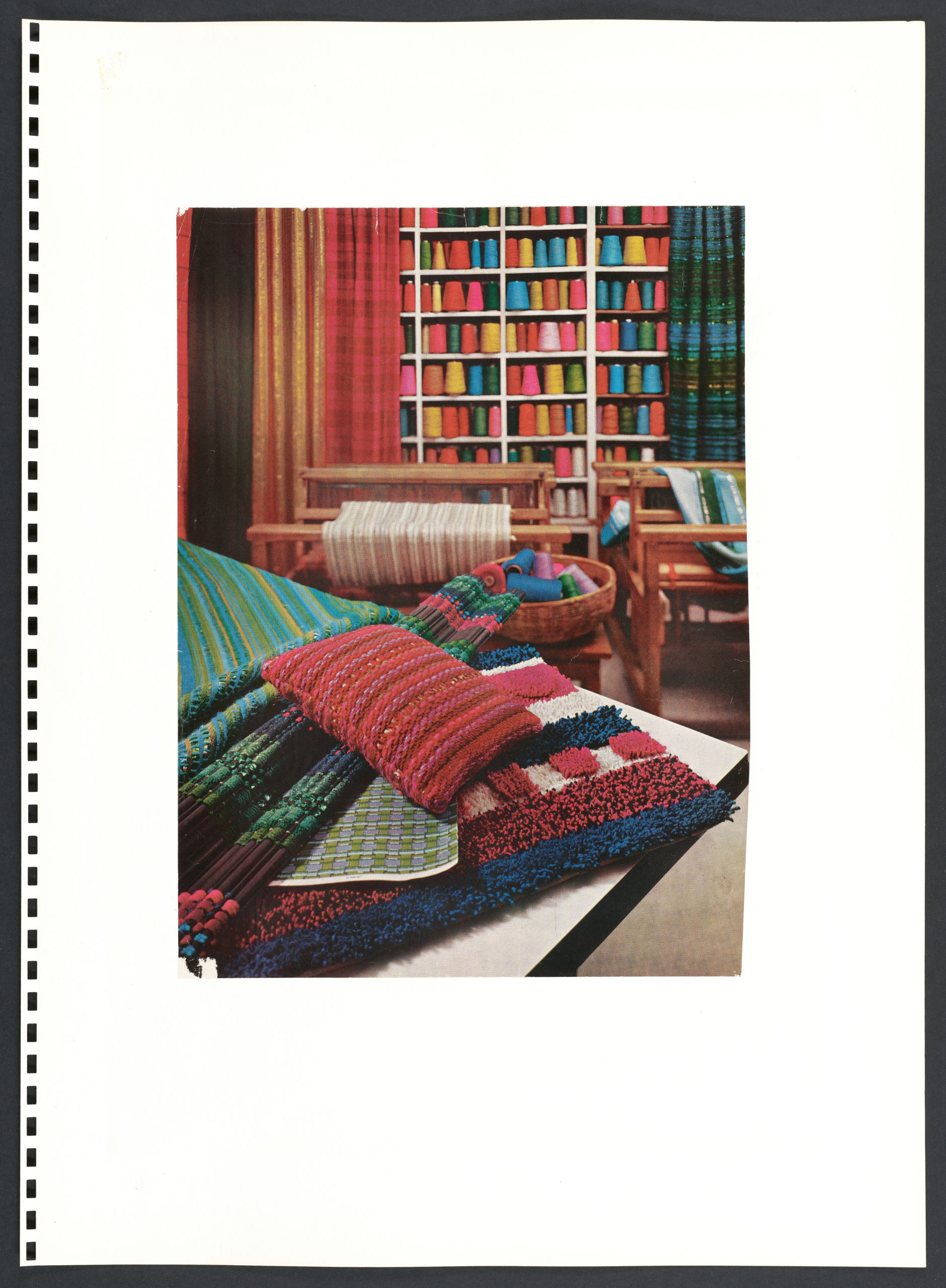

Dorothy Liebes in her Sutter Street studio, San Francisco by Charles Steinheimer (American, 1914–1996), circa 1947. The Life Picture Collection.

Brown also asserts that “there isn’t a student of weaving in the past 70 years who hasn’t been touched by Liebes’ work. Collections of her handwoven samples were planted like seeds at institutions across the country, where they continue to be used in Fiber programs today.”

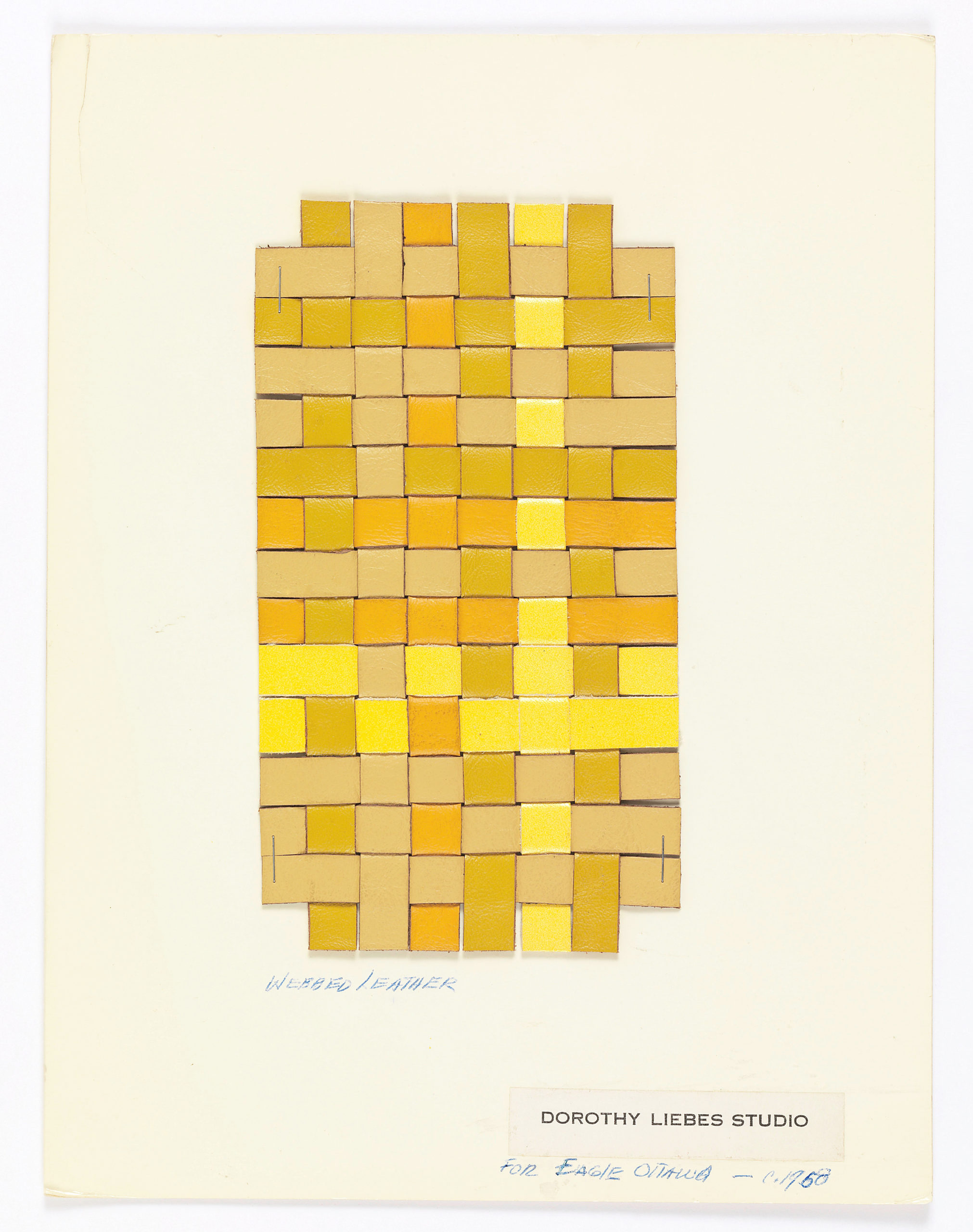

Liebes had a lifelong respect for handweaving. At the age of 23, she bought her first loom after a two week summer course at Hull House in Chicago, where she was introduced to weaving and dyeing. That beginning blossomed into a garden of influence beyond anything she might have imagined at the time. One example, when Ed Rossbach, esteemed professor of design at UC Berkeley and my teacher in the 1970s, attended that 1939 Fair and saw what Liebes had created, he knew he had to learn to weave. Later, he would take his work off the loom and is now recognized as the pre-eminent influence in the rise of basketry as a sculptural art form. But Liebes was there at the beginning, and like her, he incorporated non-traditional materials into his work.

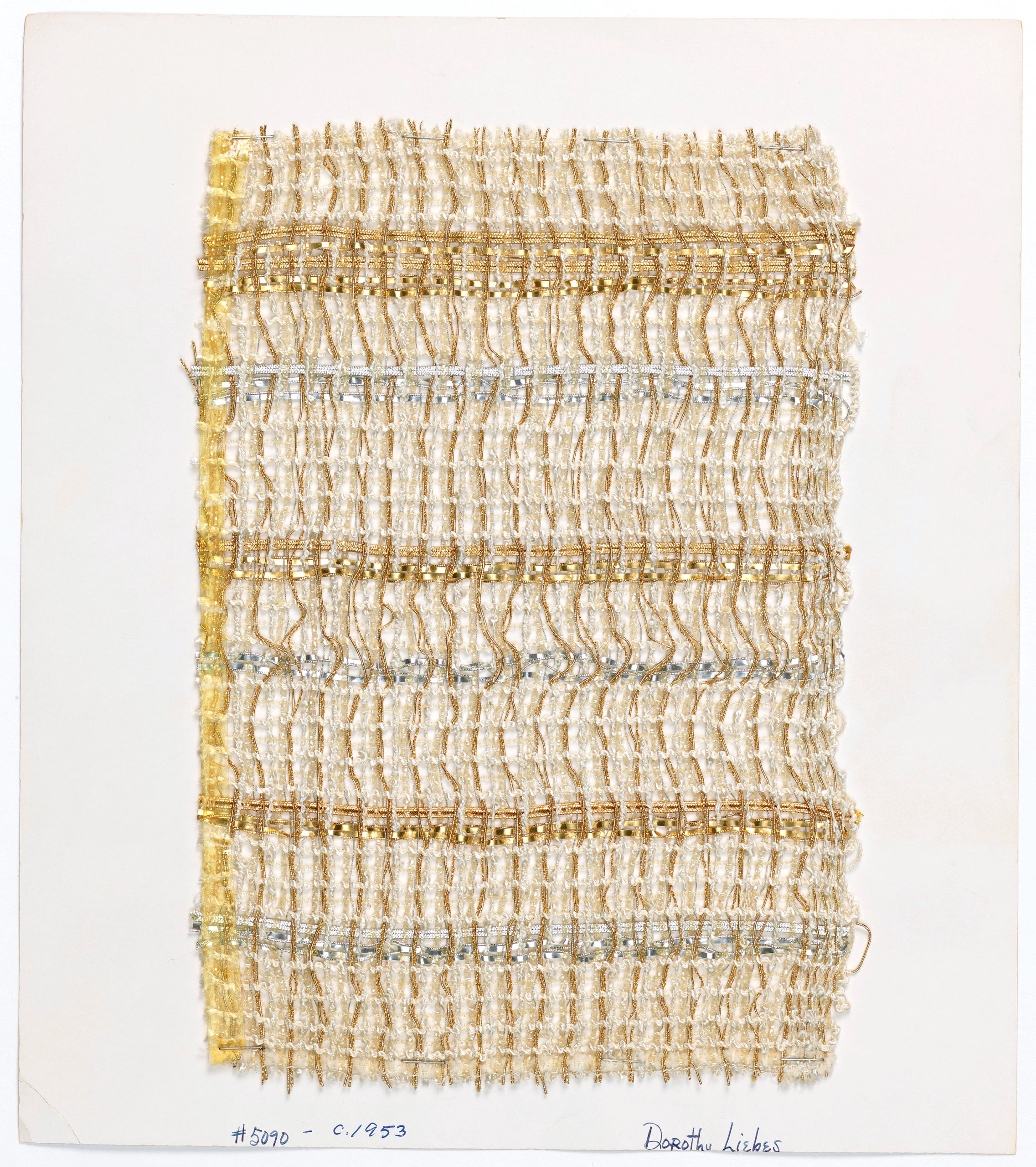

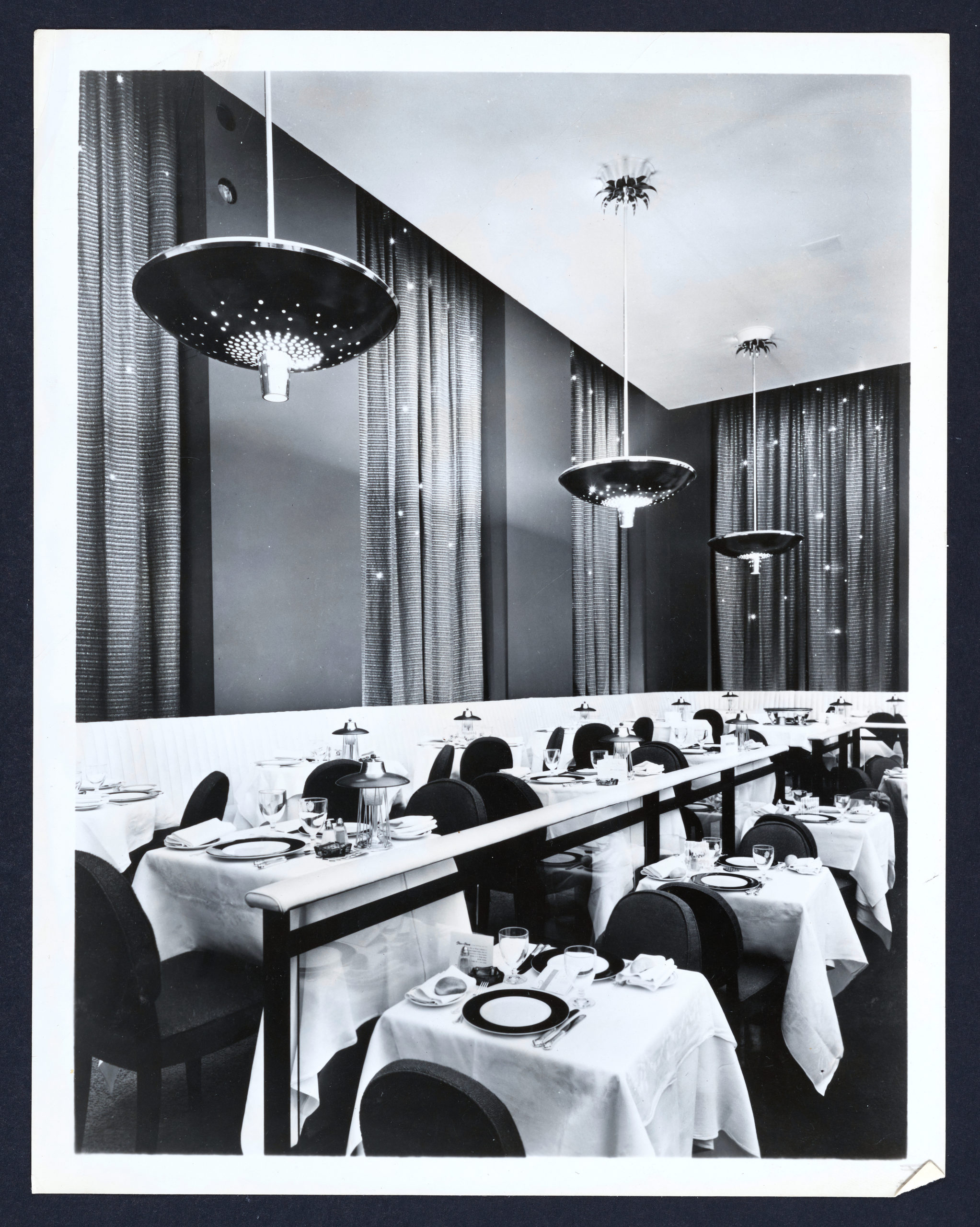

Those unconventional materials and wildly expanded combinations of color and texture in fabric and textiles are chief characteristics of Liebes’ design, as is her use of light. She had the ability to see in an interior space what would enhance the given light conditions and designed textiles specifically for that space, both draperies and upholstery, and later rugs and wallpaper. She did this for private homes, collaborating with architects who championed modernism, like Wright and Samuel A. Marx. She did it for public spaces — the Persian Room at the Plaza Hotel and other restaurants and night clubs in New York City and beyond — making use of her ever-expanding toolkit of metallic fabrics and threads. Glitter and glamour came to be associated with her name.

Persian Room at the Plaza Hotel, New York City, 1950; Interior design by Henry Dreyfus; (American, 1904-1972), Drapes laced with tiny electric lightbulbs and woven blinds designed by Dorothy Liebes; Henry Dreyfus Archive, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, 1972.

Though Liebes was first known as a weaver, she insisted that she be understood as a designer and it was as a designer that she came to have her great influence. Her studios, first in San Francisco and then in New York City, became places of experimentation, problem solving and collaboration. Working with younger designers, welcoming the talented regardless of race, religion, gender or sexual orientation, she encouraged them to follow their own creative directions. In the 1950s and 1960s, she influenced and became friends with renowned designers like Jack Lenor Larsen, who called her “the greatest craftsman of his time.”

Liebes was not just a designer for the home and public spaces. She was also a fashion designer. As early as 1938, Women’s Wear Daily, the leading fashion trade journal, recognized the duality of her talent in home furnishings and her chic style in women’s fashion. Liebes considered her designs textile art, with a capitol A, whether for the home or the body. The glamorous “Liebes look,” created by her textiles and what she wore herself, came to be in demand from Hollywood to Seventh Avenue. The “Liebes look” was characterized by vibrant colors, sophisticated structural patterns, complex textures and unconventional materials. She became sought-after as an arbiter of taste.

Costume designer Travis Banton created an emerald, gold and black swing jacket for Lucille Ball’s onscreen attire in the film Lover Come Back that was also used in a publicity photo. It included Lurex, the revolutionary metallic yarn that Liebes was just beginning to promote. It is this introduction of Lurex in the 1940s, yarn that became her signature material, that was her most significant achievement in the world of fashion. Again, light was the magic ingredient. Lurex textiles glittered, especially when the wearer moved. Over the next decades, Liebes expanded the use of Lurex in curtains, wall coverings, upholstery and automotive fabrics. An ambitious promoter of the Dobeckmun Company that made the fiber, she earned it a spot at the 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels with her design for curtains in the American Pavilion.

Dorothy Lamour surrounded by loop-fringe textile designed by Dorothy Liebes, Photoplay, March 1938. Private collection.

Liebes’ success in the 1930s, designing custom fabrics for architectural commissions and for the bespoke market encountered a challenge in the 1940s with the coming of war and the resulting scarcity of materials. The challenge was one she embraced as she wanted to reach a larger market, believing that well-designed and well-made fabric should be available to everyone.

Without denying the great pleasure of making things by hand, she began to explore the possibility of mechanized production. She wanted to achieve the quality, look and feel of handwoven fabric in machine-made, mass-market textiles. She began working directly with industry as a design consultant and continued to do so until the end of her career.

Dorothy Liebes was born on October 14, 1897, in Santa Rosa, Calif. Her education included the study of art education at Santa Rosa/San Jose Teachers College and she graduated Phi Beta Kappa from the University of California, Berkeley, with a BA in decorative art, architecture and applied and textile design. During this time, she also studied tapestry technique with eminent scholars of Persian art. In 1924, she studied painting and color at the California School of Fine Arts, San Francisco. She taught art in the Piedmont, Calif., public schools until 1926. Born, brought up and educated there, Liebes personified the spirit of California.

Dorothy Liebes Studio, New York City, as photographed for House Beautiful, October 1966. Dorothy Liebes Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Since the days of the Gold Rush, California had captured the imagination as a place of promise and possibilities never before dreamed of. Liebes bowed to this California legacy in a textile she called “goldrush gingham” — blond cotton glistening with gold, copper and silver metallic yarns. She boldly broke the rules in her field, adventuring far beyond California’s shores to discover the richness of world textiles. “Travel,” she said, “is the staff of life of the designer.”

Not just ideas from European textiles but also those of Asia and the Pacific, made their way into her designs. In 1937, she was in Hawaii exhibiting at the Honolulu Academy of Art, and included in her Bishop Museum display a series of panels made from Indigenous material that she had commissioned. By 1961, Liebes was traveling to the ancient textile centers of Hamamatsu, Japan and Ahmedabad, India. She brought her knowledge of international textile markets and an approach to manufacturing that used handmade weaving samples. Throughout her career, from 1940 to 1971, she was an invaluable advisor and consultant to such venerable Asian centers and to American manufacturers such as Bigelow-Sanford Carpets, DuPont, Goodall Fabrics and United Wallpaper. Finally, her career retrospective was held in 1970 at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts in New York and later traveled to the Smithsonian in Washington DC, and other venues around the country. She died in 1972.

“A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes” is organized by Susan Brown, associate curator and acting head of textiles at Cooper Hewitt, and Alexa Griffith Winton, design historian and educator, currently serving as manager of content and curriculum, Cooper Hewitt. Winton has researched and published on the work of Liebes for more than 15 years. Well-researched scholarly essays in the catalog include “Curtain Walls: Dorothy Liebes and the Modern American Interior” by John Stuart Gordon, “Vibrance and Luminosity: Textiles Designed for Light” by Alexa Griffith Winton, “The Idea Factory” by Susan Brown, “Modern Weaving’s Global Ambassador” by Emily M. Orr, “Modern Fashion’s Secret Weapon” by Leigh Wishner, “The Liebes Look: Better and Better for Less and Less” by Monica Penick, and “Fission: Design and Mentorship in the Dorothy Liebes Studio” by Erica Warren. An extensive chronology and bibliography are included.

Dorothy Liebes Studio, New York City, circa 1957. Dorothy Liebes Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

“A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes” will be on view at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum through February 4. The Museum is at 2 East 91st Street. For additional information, www.cooperhewitt.org or 212-849-8400.

[EDITOR’S NOTE: Pat Hickman is a fiber artist and textile historian; she is married to Gail Hovey, a writer and editor. They are the mother and stepmother, respectively, of editor Madelia Hickman Ring.]