By Laura Beach

Becoming America: Highlights from the Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection of Folk Art. Edited by James Glisson, with contributions by John Demos, Jonathan and Karin Fielding, Robin Jaffee Frank, James Glisson, Stacy C. Hollander, Christina Nielsen, Sumpter Priddy, Elizabeth V. Warren and David Wheatcroft. The Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, Calif. Distributed by Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2020, $50 hardcover.

With most American museums and galleries shuttered, communing with collections not our own is something we do vicariously these days, whether diving into a virtual tour online or thumbing through a glossy guide.

As remote experiences go, Becoming America: Highlights from the Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection of Folk Art is an especially satisfying one. Part personal biography, part cultural history, the volume profiling the California couple’s gift to The Huntington arrays a choice variety of primitive portraits and landscape paintings, furniture, textiles, painted boxes, pottery, hearth iron, lighting and related decorative art, most of it made in New England between 1680 and 1870, all of it exceptional in its imaginative quality and execution.

Jonathan Fielding, MD, a former director of the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health and a professor at UCLA, and his wife, Karin, a retired marketing and communications professional who serves on the board of New York’s American Folk Art Museum, write that they were novices when they began collecting in the early 1990s for their vacation retreat, a 1768 farmhouse on the Maine coast. They began by browsing antiques shops and attending local auctions, and sought guidance from local dealer Ross Levett. Before long, they were working with some of the folk art field’s leading experts, David Wheatcroft chief among them.

“Because of the modesty of our home and its rural location, we focused primarily on furniture created and used by people who lived and worked in the country. From furniture, we moved on to paintings, pottery, needlework, lighting devices and other decorative and utilitarian items,” write the Fieldings, who were drawn to distinctive pieces, more for their authenticity and character than for their sophistication.

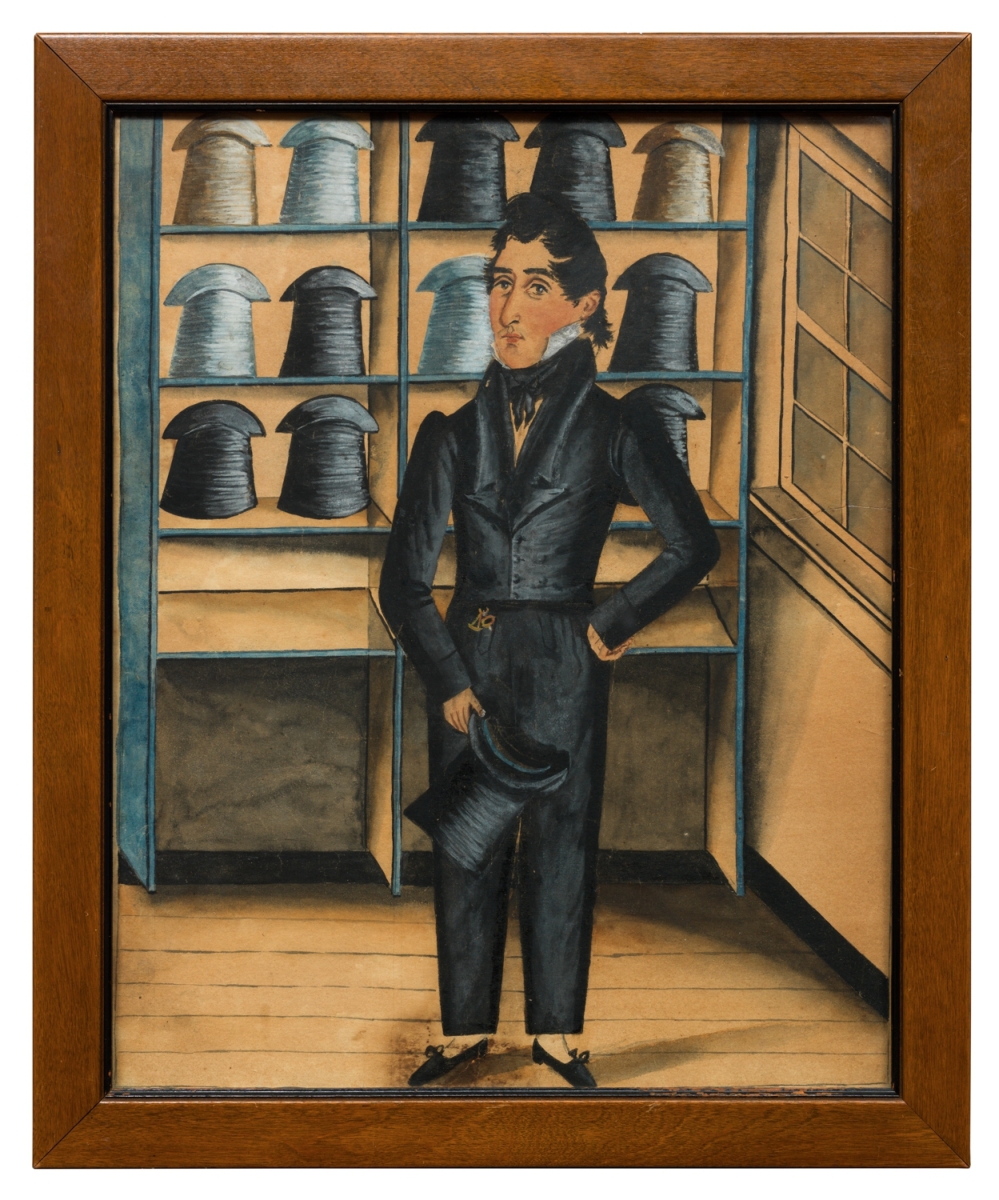

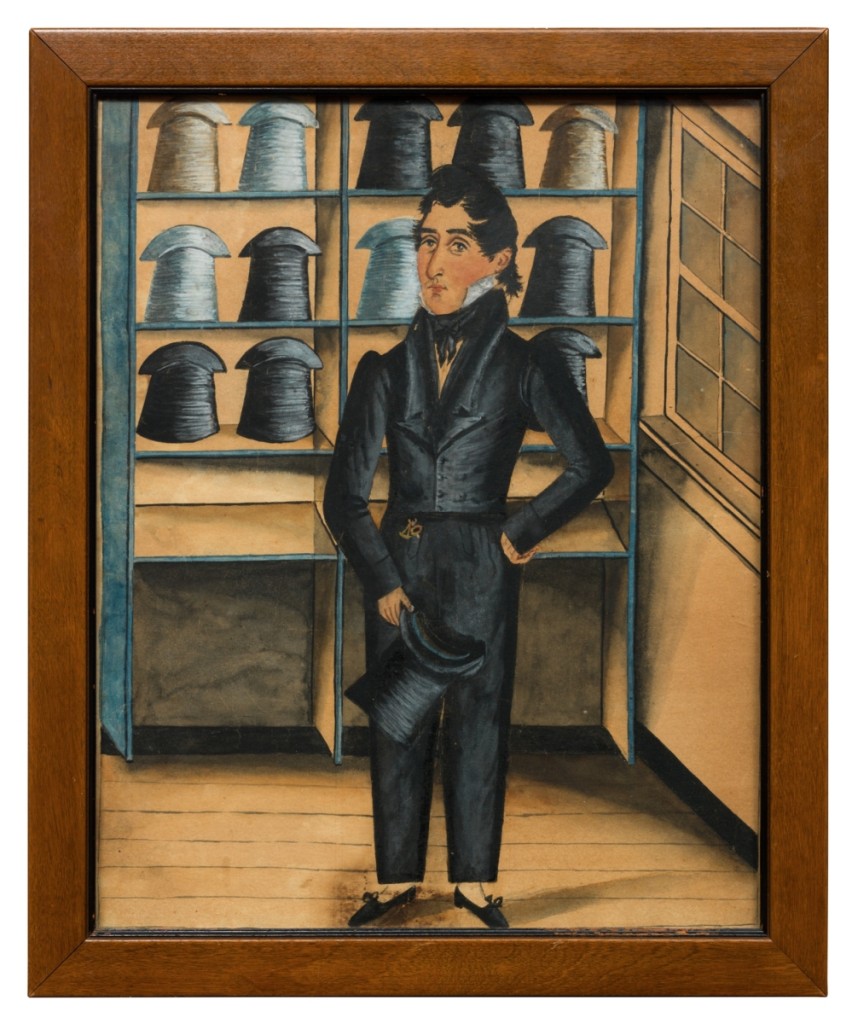

Portrait of Hatter John Mays of Schaefferstown by Jacob Maentel, circa 1830. Watercolor, gouache, ink and pencil on paper, frame 18 by 15 inches. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Gift of Jonathan and Karin Fielding. Photography © 2014 Fredrik Nilsen.

As their collection grew in size and importance, the couple began bringing favorite objects home to Los Angeles. Their West Coast guests were mystified or, worse, indifferent to the New England curiosities. The Fieldings write, “That’s when we recognized that we wanted people not only to enjoy these uniquely American decorative objects but to understand and appreciate their importance to the history of our country. We wanted to make our collection widely available as a teaching tool…the objects deserved to be in a place where anyone could experience them.”

The Fieldings developed a list of qualities they sought in a partner institution, where they hoped a portion of their collection would be permanently on view and woven into changing exhibitions. They sought an institution with a compatible collection, a demonstrated interest in American art, adequate resources, good visitation and a forward-looking approach to technology. Ideally, it would be close to their home. Located near Pasadena in the city of San Marino, 12 miles northeast of downtown Los Angeles, The Huntington fit the bill. Over 250 items are now installed in “Becoming America: Highlights from the Jonathan and Karen Fielding Collection,” housed in the Jonathan and Karin Fielding Wing, an addition to the museum’s Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art.

As is increasingly common in collections catalogs, the pictorial presentation is accompanied by essays penned by guest experts. Guided by the collectors’ interest in objects as a window on the past, contributors wrote pieces as much about listening to the collection as looking at it.

Now curator of contemporary art at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, former Huntington curator James Glisson, the book’s editor, recalls the arrival of 250 objects from the Fielding collection at The Huntington in 2016. For the first time, he writes, the museum could explore with visitors the lives of middle-class Americans in rural New England.

Glisson’s interview with David Wheatcroft, now living in Pennsylvania, provides insight into the origins and motives of the noted dealer, a former art student first attracted to the graphic qualities of quilts in the 1970s. As a consultant to the Fieldings, Wheatcroft says his chief role was providing market “context.” He went to the mat to acquire for the Fieldings two pieces readers may remember, an extraordinary carved and painted figure by Asa Ames and an anonymous still life painting formerly in the collection of singer Andy Williams. Skinner auctioned the latter for $480,000 in 2013.

High-back Windsor armchair with writing arm attributed to Ebenezer Tracy Sr, late Eighteenth Century. Wood and green paint, 36-7/8 by 36¼ by 31 inches. Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection.

The most unexpected essay is by John Demos, a collector of early New England artifacts and the Samuel Knight Professor of History Emeritus at Yale University. “If only antique furniture could talk, what would it tell us,” the scholar asks intriguingly. Organizing his thoughts under the headings “Making,” “Using,” “Meaning” and “Survival,” Demos observes that the familiar market terms high-style, country and primitive “correspond very roughly to what we now call class difference: upper, middle and lower; in short, they reflect different levels of wealth and social rank.” He is particularly drawn to chairs, “humanlike,” with their assortment of backs, arms, legs and feet. He concludes by inquiring why we care about old furniture, noting, “We do not truly own these things; they lie beyond such claims. They both precede and outlive us. We receive them from the past, preserve them as best we can, and pass them along to the future. We partake of their journey. Is this not its own reward?”

Addressing his remarks chiefly to the paint-decorated objects in the Fielding collection, dealer Sumpter Priddy returns to groundbreaking scholarship he published in his award-winning 2004 book American Fancy, Exuberance in the Arts, 1790-1840.

Independent scholar Elizabeth V. Warren thoroughly examines needlework, samplers, rugs and quilts – there are 39 of the latter – in the Fielding collection. She writes, “They were expressions of beauty in the lives of women who frequently had no other socially acceptable outlet for their creativity,” adding, they “went far beyond necessity. They are truly works of art.”

Stacy C. Hollander, former deputy director for curatorial affairs, chief curator and director of exhibitions at the American Folk Art Museum, discusses early American landscape and still life painting as reflected in the Fielding collection. The paintings, she writes, reveal a “telling dichotomy in the American character as it developed in the years just before and following the Revolution: a push-pull between stubborn iconoclasm and the need to prove worth in European eyes.”

Becoming America concludes with an essay on portraiture by Robin Jaffee Frank, director of Silvermine Art Center. The “dominant form” of painting in Nineteenth Century America, portraiture “offered a sense of not only how the subjects actually looked but also how they wanted to be seen by their peers and remembered by posterity,” she notes.

For this reader, the most compelling objects in the Fielding collection are the most humble, primitive lighting and hearth equipment made extraordinary by everyday Americans with the kind of imagination and initiative that, writ large, built this country.

The Fieldings allow that “there is no substitute for being with an object, to feel its essence, gauge its attractiveness and carefully examine it for ‘apologies.'” May this book be only the beginning of the public’s joyful interaction with an uncommonly compelling assemblage.