This carved stone foot, made to hold up the front end of a five-plate stove, was made for the house of Philip Erpf, a storekeeper in Schaefferstown. His name and the date of 1765 are inscribed above and below a relief-carved flowering vine. Similar carving is found on Pennsylvania German gravestones and the datestones of houses. —Gavin Ashworth photo

By Kristin Nord

TRAPPE, PENN. – There were great stirrings of life at Historic Trappe on a recent morning as volunteers gathered to work on a project at The Speaker’s House, home of the first speaker of the House of Representatives in the US Congress, and just a short walk from Dewees Tavern Museum’s galleries.

The pandemic discouraged volunteer efforts for a while, Lisa Minardi, Historic Trappe’s executive director, commented on that day, but the restrictions on gatherings had lifted, alongside the joyful news that the donation of 56 artifacts from the late William K. du Pont’s Rocky Hill Collection had become official. Minardi, a leading scholar of Pennsylvanian German Studies and Historic Trappe’s spirited mover and shaker, likened this gift “to the Hennage bequest to Colonial Williamsburg,” with this caveat – while the Hennage gift “crowned” the Williamsburg collection, the du Pont donation “is establishing a solid foundation for our collection on which to build for the future.”

Du Pont’s Americana archive contains significant reference books on American furniture, ironwork, long rifles, powder horns, needlework, Pennsylvania German folk art, as well as the research files for his private Americana collection. It will share quarters with some 36 boxes of historic Pennsylvania German manuscripts and other reference works that were recently donated from the collection of the late Dennis K. and Linda D. Moyer. Ursinus College students have been tapped to digitize the manuscript collection.

It’s been nearly two years since the Trappe Historical Society and the Speaker’s House merged under the nonprofit umbrella, Historic Trappe, an organization site which includes three homes occupied by the illustrious Muhlenberg family and the renovated Dewees Tavern, with its ground floor repurposed into a colorful repository of well-appointed galleries. Henry Muhlenberg (1711-1787) was the Lutheran missionary sent from Germany to serve Pennsylvania colonists and is seen as the patriarch of the Lutheran church in America; his sons Gen. Peter Muhlenberg, and Frederick, who served as the first speaker of the House in the US Congress, played significant roles in the development of the new nation.

Most German immigrants made the long ocean voyage to the New World with a chest filled with provisions such as clothing, bedding, food and medicine. Because they were subject to breakage, theft, vandalism and other mishaps, these immigrant chests were often reinforced with iron straps. Immigrant’s chest, Germany, 1744. Pine and iron. —Gavin Ashworth photo

“With its combination of three historic sites and The Center for Pennsylvania German Studies with its five exhibition galleries, research library and archives, Historic Trappe has emerged as the country’s pre-eminent institution for the study of Pennsylvania German art and culture,” Minardi said.

Philadelphia had become the port of arrival for approximately 80,000 German speakers in the Eighteenth Century who were lured by William Penn’s policy of religious tolerance. Most hailed from Lutheran or Reformed churches, but there were several other religious denominations, including the Amish, Mennonites, Moravians and Schwenkfelders, that fanned out in settlements throughout the Pennsylvania countryside. They brought their traditional crafts and soon turned to the region’s distinct natural resources to produce redware, decorative furniture, beautifully crafted ironwork, textiles, and the exquisite fraktur.

Minardi first got involved with preserving Trappe’s historic buildings as an undergraduate at Ursinus College when she joined a grassroots effort to save the Speaker’s House from the wrecker’s ball in 2002. At the same time, she was soon well on her way toward building a reputation as a leading scholar in her field. As a dual major, she wrote her history honors thesis on the Muhlenberg family, and completed a catalog of the Ursinus College fraktur collection for her honors thesis in museum studies. She then pursued graduate studies at the Winterthur Program in Early American Culture. As a curatorial intern and later assistant curator there, she built the fraktur collection into one of largest and finest in the country.

Minardi first encountered William K. du Pont in 2005: “I was 22 when I first met Bill as a Winterthur fellow on a visit to see his collection at Rocky Hill,” she recalled recently. “We were kindred spirits from the get-go; his collecting interests had shifted to focusing primarily on Pennsylvania German and Quaker furniture by the time we connected, which was exactly what I was beginning to study in earnest. He was keenly interested in not only the aesthetics of the objects, but also in the stories behind the individual pieces – who made them, who owned them and how they have passed down through the centuries. He pushed me to dig deeper and to make new discoveries about not only great objects in his own collection but at Winterthur and really anywhere.”

Minardi served as his curatorial adviser for many years, visiting him at Rocky Hill, his farm near Newark, Del., and ultimately working to catalog his holdings. She and her husband, the late Philip W. Bradley, spent hours with Bill at Rocky Hill in 2020 just a day before he died unexpectedly. “Bill told us that night he thought he had another ten years of collecting in him.” This was not to be, though by the time du Pont left this world he and Minardi had in many ways fine-tuned his collection. Among his passions were Chester County line-and-berry inlaid furniture, sulfur-inlaid furniture and Pennsylvania German painted chests.

Behind the scenes, du Pont had enthusiastically bolstered Minardi’s vision for Historic Trappe, whether it was donating historic bricks for the reconstruction of chimneys at the home of Frederick Muhlenberg or providing antique fireplace tools, kitchen utensils and many decorative accessories when Minardi overhauled the Henry Muhlenberg House in 2017. He also made significant long-term loans to the Center for Pennsylvania German Studies, among them an immigrant chest dated 1744, one of only a handful known to survive, which likely carried a family’s worldly goods on its transatlantic voyage to Pennsylvania; a plank-seat chair from the Moravian Sisters’ House in Nazareth, Penn., made with sawn-out backs and legs shaped by a spokeshave; fraktur from major artists, including a writing sample by the schoolmaster Christian Alsdorff; and a table thought to have served as a writing desk at Ephrata circa 1750, made of walnut, tulip poplar and pine.

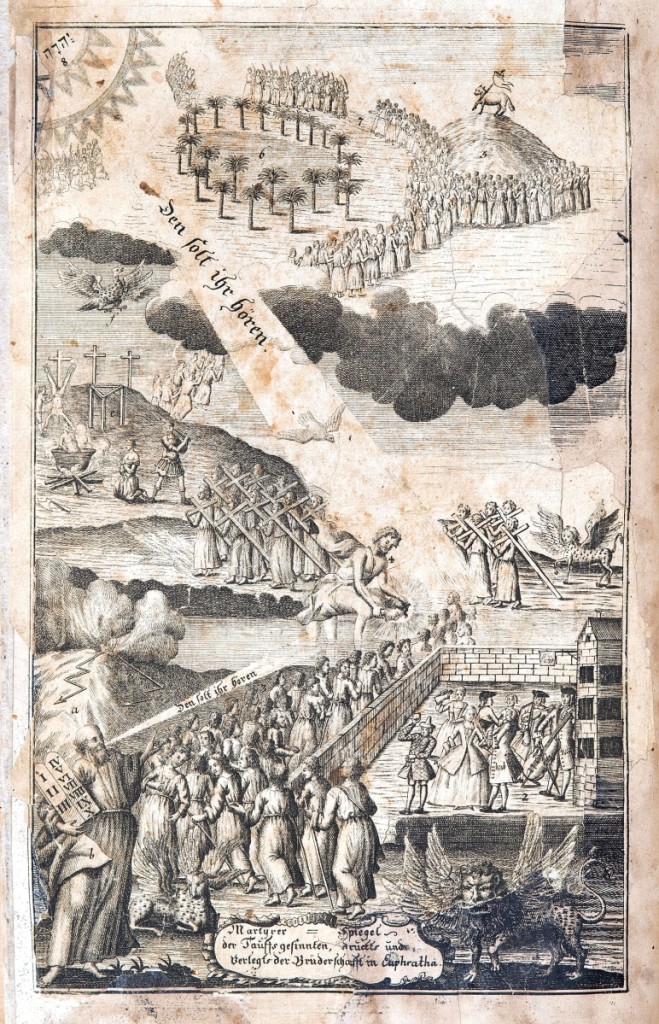

An unusual wardrobe and desk, circa 1780-1800 from Lancaster or Lebanon County, distinctive for its floral inlay as well as its architectural cornice, is among du Pont’s major gifts, as is the 1,512-page German-language translation of the Martyrs’ Mirror, published originally in Dutch in 1660 in response to early Christian and Anabaptist persecution. This book, which took more than three years to complete, was the largest printed in colonial America.

As Minardi leads a tour through the tavern’s galleries, she points out several other du Pont donations, including a rare raised-panel door, circa 1775, in which then-customary two wrought iron hooks were used to display decorated hand towels, and a wrought iron fork-spatula that had arrived unceremoniously one day simply because du Pont felt she needed it for display.

“Bill attended the grand opening of the Center for Pennsylvania German Studies in September 2019 and was beaming ear to ear the entire time,” Minardi recalled. “He was so thrilled to see the objects he loved so much getting their full due.”

Historic Trappe is all the more astonishing for the cadre of volunteers Minardi has assembled, by matching the interests and talents of local residents and by reaching out to students at her alma mater.

“Lisa is superbly organized, and she is not afraid to ask for help,” Jim Kelly, a Pfizer retiree who oversees the maintenance of the grounds, said. Kelly has marveled at her ability to galvanize workers; when she sets her sights on accomplishing something, he said simply, “she gets it done.”

Jenna Detweiller, an Ursinus alumna, has helped restore the kitchen garden on the Speaker’s House property and runs a farm stand there during the growing season. “Lisa has set many other people up with internship and volunteer opportunities focused on their own topics of interest, such as historical reenactment, sewing, building, archaeology, library work and other topics. Delving into the region’s history in this way, she said, has made her return to her own family story.

While the museum’s inaugural exhibition in the fall of 2019 was organized in honor of the nearby college’s 150th anniversary, upcoming exhibitions will focus on the du Pont gifts as well as showcase the redware potters of Montgomery County. The latter exhibit was deferred by the pandemic but tentatively is scheduled to open in 2023.

Other long-term loans have come from the Dietrich American Foundation and the Wunsch Americana Foundation, which have been used to great effect.

“We will catalog the du Pont Americana reference library books first and make those available in our online database, then the research files. I would expect to have everything up by summer 2022,” she said.

Overall, Historic Trappe is building on this momentum. Minardi said that a great deal of gratitude is owed to those who continue to support Historic Trappe – and in particular, to du Pont, who “continually inspired me to do my best work.”

“Bill pledged that he would donate these pieces to Historic Trappe over time and we are ever so grateful to his daughter for following through on that promise.”

For information, www.historictrappe.org or 610-489-7560.