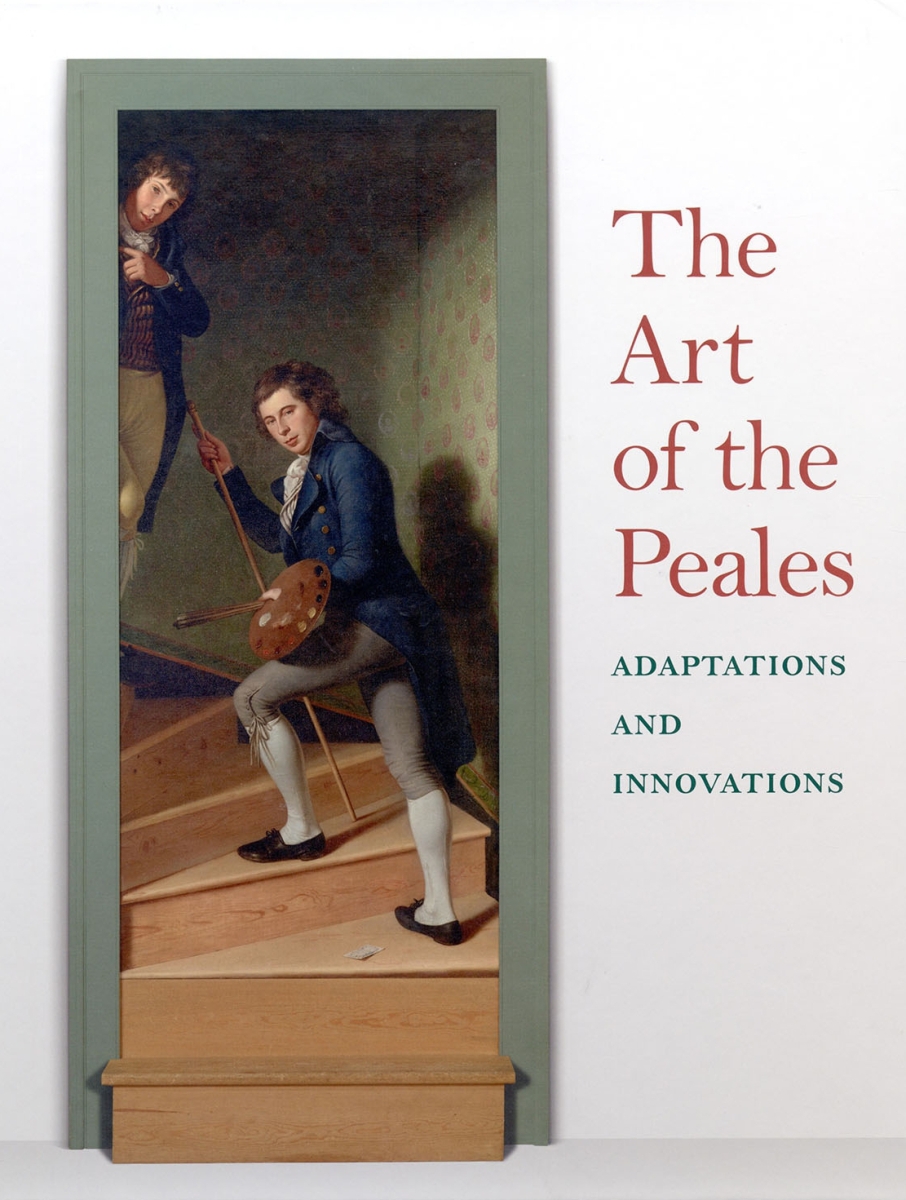

The Art of the Peales in the Philadelphia Museum of Art: Adaptations and Innovations by Carol Eaton Soltis, Philadelphia Museum of Art, in association with Yale University Press, New Haven, New Haven and London, 2017; 334 pages, hardcover, $65.

The Peale family, working in Philadelphia from the late Eighteenth Century to the early Twentieth Century, comprised the earliest artistic dynasty in the United States. Pre-existing scholarship on the Peale family is extensive but relatively narrow in scope, focusing primarily on a few of the family members working in various artistic genres.

An opportunity to reinvigorate the Peale family scholarship was presented when Philadelphia philanthropist and art patron Robert L. McNeil Jr gifted his collection, which included many Peale family works, to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Carol Eaton Soltis, the museum’s project associate curator of American art and a renowned scholar, spent years thoroughly researching the works in what had then become the largest repository of Peale family works in the world. The Art of the Peales is the fruit of that labor and presents a full and lavishly illustrated appreciation of every member of the Peale family of artists, their working practices and their lasting artistic influences.

The Art of the Peales will have a long-term impact on the field of American art, for several reasons. Not only does Soltis take a fresh and broader look at this artistic dynasty, but her research reveals new insights into the family that explain the reasons for its staying power and influence in American art.

Soltis begins with a thorough examination of the family patriarch, Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). The most well-known artist of the family, his works are given improved context and prominence through her research and analysis of his formative years, as well as the artists and works that influenced him. New meaning is given to familiar portraits, such as those he did of prominent Philadelphia families, George Washington or his own family, including “Mrs Peale Lamenting the Death of Her Child (Rachel Weeping),” “The Staircase Group (Portrait of Raphaelle and Titian Ramsey Peale)” and his self-portrait, “The Artist in His Museum.”

Having dispensed with her examination of Charles Willson Peale’s “grand manner” portraits, Soltis turns her attention to his miniatures and those done by the other miniature portrait painters in his family. Rather than address each artist individually, Soltis has organized her scholarship thematically, by generations. In doing so, she can illuminate the full breadth and depth of the Peale artistic tradition, revealing the unique dynamics that allowed for various family members to simultaneously respond to, borrow or adapt the forms, techniques and compositions of each other while concurrently developing their own individual styles and areas of expertise.

“Portrait of Yarrow Mamout (Muhammad Yaro)” by Charles Willson Peale, 1819, oil on canvas, purchased with the gifts (by exchange) of R. Wistar Harvey, Mrs T. Charlton Henry, Mr and Mrs J. Stogdell Stokes, Elise Robinson Paumgarten from the Sallie Crozer Hilprecht Collection, Lucie Washington Mitcheson in memory of Robert Stockton Johnson Mitcheson for the Robert Stockton Johnson Mitcheson Collection, R. Nelson Buckley, the estate of Rictavia Schiff, and the McNeil Acquisition Fund for American Art and Material Culture, 2011, courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Soltis cites a variety of motives for this phenomenon, including a motivation to develop competency in a particular genre, to assist a family member in the completion of commissions or to capitalize on a demand for a type of work made popular by another family member.

Subsequent chapters follow in this pattern, showing the evolution and development of Peale artists working in the genres of landscape, still life, nature studies and trompe l’oeil works. The reader is treated to the true wealth of talent in this remarkable family that previous scholarship has only hinted toward.

The extent of Soltis’s research gives much-needed exposure to lesser-known but equally remarkable and captivating works, such as “Yarrow Mamout (Muhammad Yaro)” by Charles Willson Peale, “Two Children with a Lapdog” by Raphaelle Peale, “A Child of the MacPherson Family” by James Peale, Rubens Peale’s “English Magpie Eating Cake,” or Titian Ramsay Peale II’s naturalistic butterflies and field studies, which he executed in both watercolor and oils.

Previous scholarship has addressed the work by the women artists in the Peale family separately. In The Art of the Peales, Soltis is unafraid to showcase their work alongside that of their male relatives and, in doing so, clearly demonstrates that their skills and artistic talents hold up under scrutiny. Rather than suffer in comparison, they shine.

Many monographs set out to be the final word in scholarship but, rather than closing the door on the research of the Peale family, Soltis opens a window for future conversations. In The Art of the Peales, Soltis takes the forward-thinking step of pointing out unexplored avenues of future study or areas in which the scholarship is lacking. She proposes a closer look at the ways in which the artists promoted themselves or how they sold their work. She suggests that early American art institutions are often overlooked as venues for selling art, as is the role of early American art brokers and private galleries. These questions seem appropriate even today, when artists working in the digital age are faced with numerous options for marketing themselves. One wonders what the Peales would have done with Instagram and Snapchat.

A final suggestion for further research is a closer examination of the work of Mary Jane Peale (1827-1902) and Anna Sellers (1824-1905), each of whom had both the training and love for art but who shunned the limelight and restricted their painting to their social circles, working within a cottage industry that survived alongside the professional art world.

Last, but certainly not least, The Art of the Peales is a tribute and legacy to Robert L. McNeil Jr, his passion for the Peale family’s artistic output, his generosity in promoting and supporting a greater understanding through research, as well as his gift to the museum. In making the funds available for this publication, McNeil generously enabled future generations to enjoy the Peales as he had.

-MHR