Four Nineteenth Century red earthenware spice jars stamped and infilled with slip that were made at the Dodge Pottery in Portland, Maine. These jars have descended through the Dodge family to the present family owner since they were originally created. Photo courtesy private owner.

By Justin W. Thomas

NEWBURYPORT, MASS. – There has been a lot of speculation through the years about the type of red earthenware made at the Dodge Pottery in Portland, Maine. Benjamin Dodge (1774-1838) became one of the few potters who produced red earthenware in the region before 1800, after training at his father Jabez Dodge’s (circa 1746-1806) business in Exeter, N.H. Archaeology has proven the area was largely dominated by exports in the 1700s by red earthenware potters in Massachusetts. There are, however, also some reports that credit Benjamin with establishing in about 1801 what is known today as the first Nineteenth Century potter’s business in Maine, but records indicate this is also when he became a landowner on Maine (Main) Street in Portland. He eventually became owner of a tavern, where he may have sold and utilized some of the red earthenware that he produced.

There is no surviving archaeology known from the site of the Dodge Pottery business today largely because of urban development. But it is known that the Dodge Pottery once operated out of a brick building that burned in 1822. Afterwards, Dodge built another brick building that he used as a tavern as well. It was in these brick buildings that Dodge and his son Benjamin Jr (1802-1876) produced red earthenware near the waterfront in Portland for decades. Nineteenth Century advertisements from the pottery placed in the Eastern Herald and the Portland City Directory suggest that the Dodges produced all the traditional forms of utilitarian red earthenware for the Portland area and probably locations elsewhere along the Maine seacoast. Among the prized objects today are green glazed flowerpots and urns, as well as urns and other forms embellished with figures in profile. Some of these types of objects are owned by the Maine Historical Society in Portland.

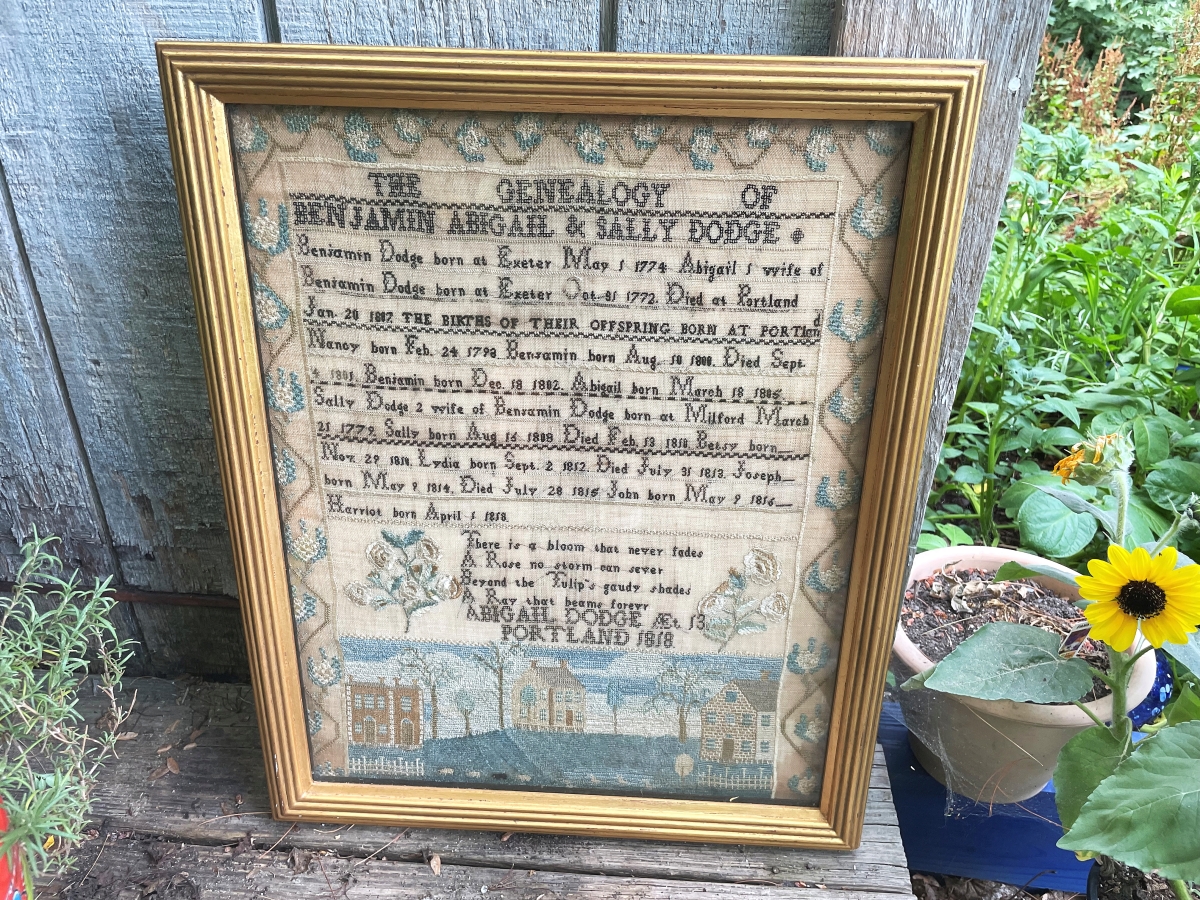

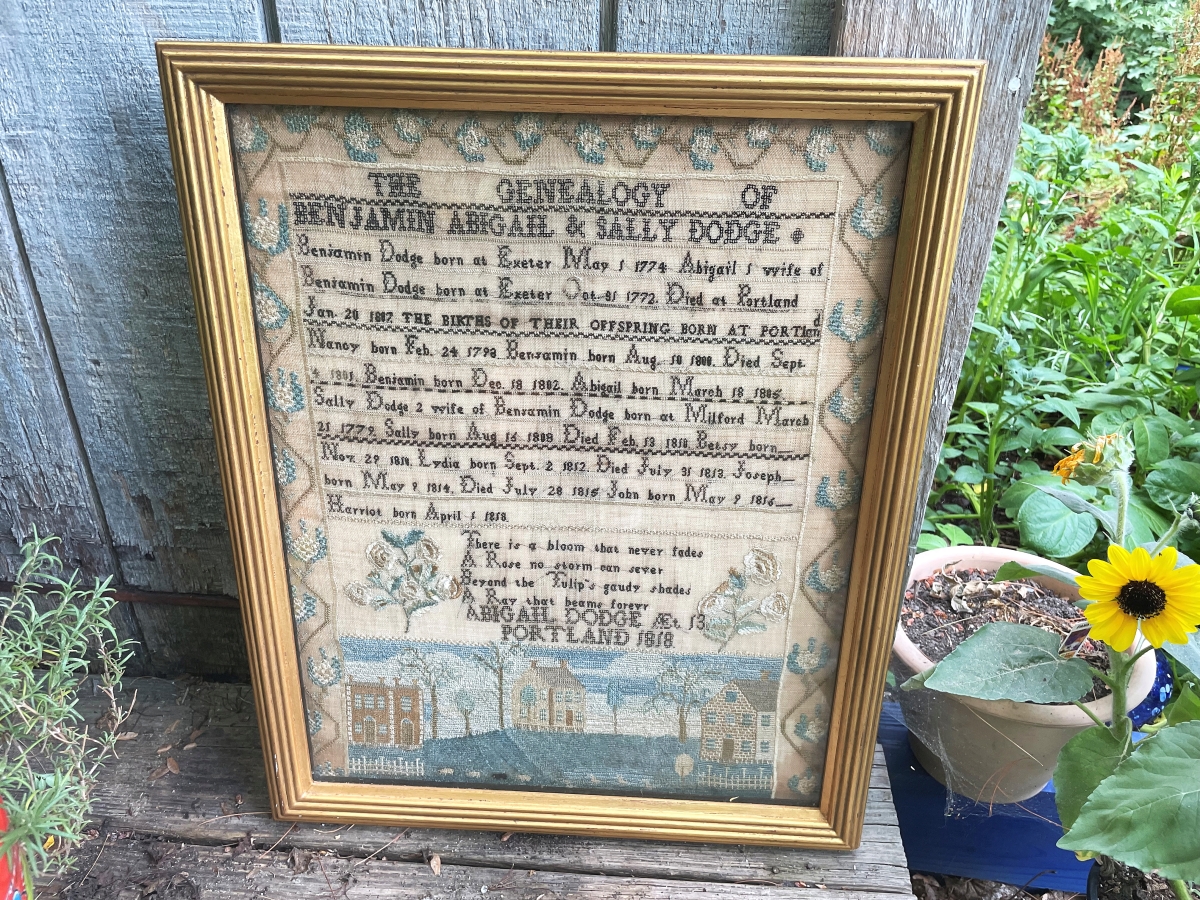

However, some new information that has just been presented to me by living descendants of the Dodges has transformed what has been decades worth of speculation into fact. First and foremost, surviving with the family today is an incredible family record sampler. It was created by Abigail Dodge (1805-1872) at the age of 13 in 1818, showing what is possibly Benjamin Dodge’s homestead, workshop and stable. The record reads, “The Geneaology Of Benjamin Abigail & Sally Dodge – Benjamin Dodge born at Exeter May 1, 1774 Abigail 1 wife of Benjamin Dodge born at Exeter Oct. 31 1772. Died at Portland Jan. 20 1807. The Births Of Their Offspring At Portland. Nancy born Feb. 24 1798. Benjamin born Aug. 10 1800. Died Sept. 4 1801. Benjamin born Dec. 18 1802. Abigail born March 18 1805. Sally Dodge 2 wife of Benjamin Dodge born at Milford March 21, 1779. Sally born Aug. 16 1808. Betsy born_ Nov. 29 1810. Lydia born Sept. 2 1812. Died July 31 1813. Joseph_born May 9 1814. Died July 28 1815 John born May 9 1816_Harriot born April 1 1818. – There is a bloom that never fades / A Rose no storm can sever / Beyond the Tulip’s gaudy shades / A Ray that became forevr – Abigail Dodge Age 13 / Portland 1818.”

Dodge family record sampler created by Abigail Dodge (1805-1872) in Portland in 1818 at the age of 13. This family record has descended through the Dodge family to the current family owner. Benjamin Dodge Sr (1774-1838) and Benjamin Dodge Jr (1802-1876) are both included who ran the Dodge Pottery in Portland. Photo courtesy of private owner.

Another sampler that may also have been created by Abigail, otherwise by another member of the Dodge family, was published in the magazine Sampler & Antique Needlework Quarterly in an article written by Connecticut author and collector Glee Krueger (1931-2018), titled, “American Architecture in Samplers (1800-1850).” The sampler is inscribed “The dwelling house ware [sic] shop and stable &c of Benjamin / Dodge was consumed by fire / Portland June 15, 1822.” This was a major fire in Portland that destroyed upwards of 20 buildings, 14 or 15 of which were houses, and the properties owned by Daniel Green, Benjamin Dodge and Joseph Gould sustained the heaviest losses. All of this information was published in the June 18, 1822, issue of the Eastern Argus.

Furthermore, there has also been discussion through the years about a type of red earthenware lidded jar manufactured with a marbled glaze said to have been produced at the Thomas Truxton Kendrick (1803-1878) Pottery in Hollis, Maine; whereas another type of jar in the exact same shape and lid from the same potter’s business adorned with various ingredients in slip has been attributed to the Dodge Pottery.

Some of the marbled jars also reside in the Maine State Museum in Augusta with the Kendrick attribution, but it is highly unlikely that these types of jars were produced at two separate businesses. This is a subject that I have been trying to research for years, previously showing in publication that these jars are closely related to other objects owned privately and by the Maine State Museum, stamped, “B. Dodge / Portland.” The marbled glaze found on some of these jars has also been a source of discussion, seeing that this type of glaze was not exclusive to any business, where similar glazes were likely produced elsewhere in Maine, possibly other parts of New England, Western New York and Ontario in Canada, among probably other places.

On the left, these types of jars with lids have previously been attributed to the Thomas Truxton Kendrick Pottery in Hollis, Maine, although they are the exact same shape and from the same manufacturer as the spice jars. On the right, these styles of glazes are not exclusive to any single pottery manufacturer; this pitcher was made at the Lorenzo Johnson Pottery in Erie County, N.Y. Lewis Scranton Collection.

Incredibly, the Dodge descendants who own the family record also own four of the lidded jars that have been in the possession of their family since they were originally created at the Dodge Pottery in the 1800s. These jars were probably made before 1838 by Benjamin Dodge Sr and are important survivors in gaining a better understanding about the production at this business, considering the lack of archaeological evidence today.

The jars are stamped and infilled with slip, reading individually, “Ginger., Cloves & Nutmeg., Allspice. And Cream Of Tartar.” Three of the jars also survive with their original lid, and each jar and lid are stamped on the base with a number no higher than six.

It is unquestionable that the Dodge Pottery in Portland was a landmark business, operating in a major maritime city that helped shape the culture of the state’s seacoast in the 1800s. In fact, the poem “Keramos,” written by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882), was published in 1878. It depicts the story of a potter. It is believed that the Dodge Pottery in Portland served as the source of inspiration for this poem.