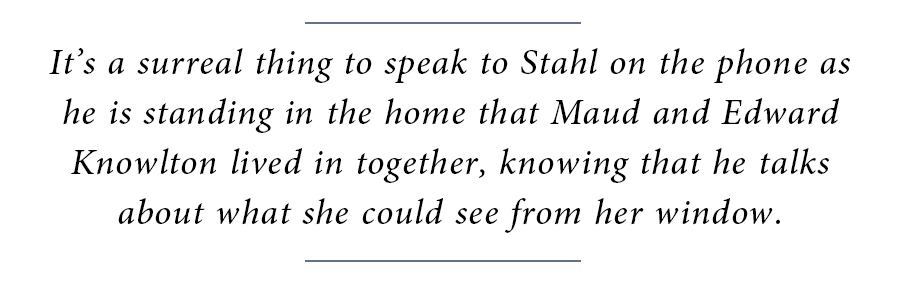

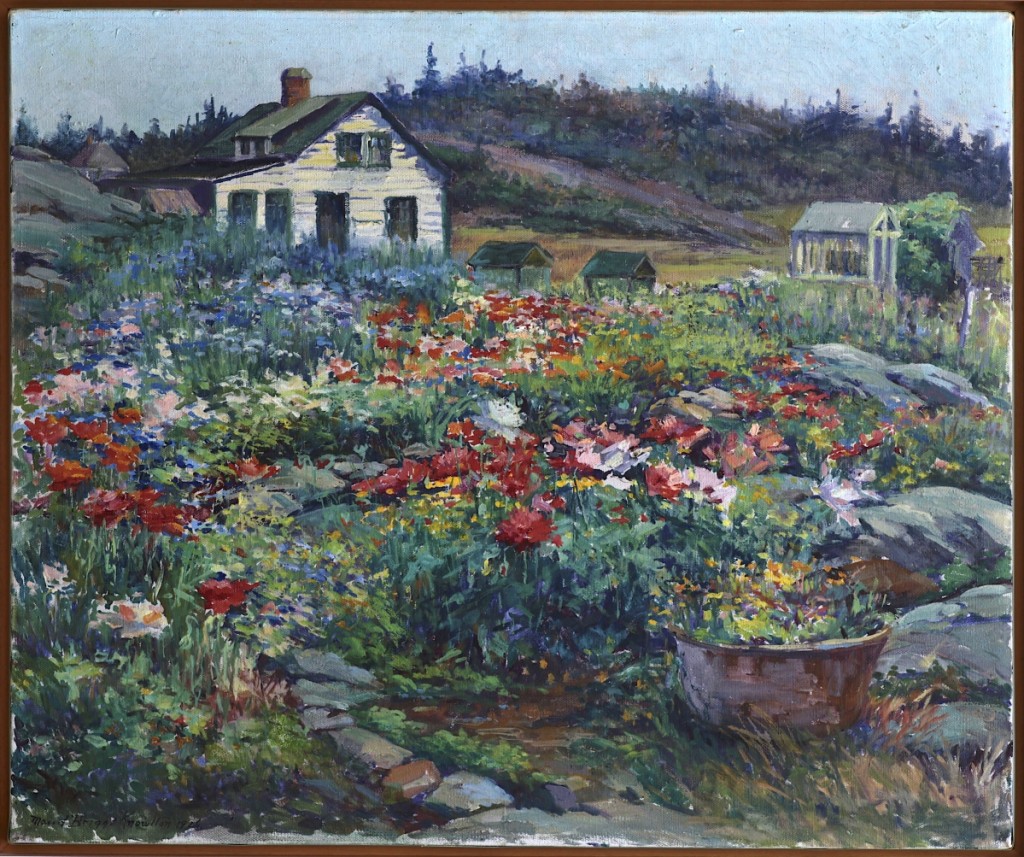

“Hilltop Garden, Monhegan” by Maud Briggs Knowlton, 1926. Oil on canvas, 5 by 30 inches. Private collection.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

MONHEGAN, MAINE – Some curators try, metaphorically, to inhabit the lives of the artists whose works they study. But for Robert Stahl, it’s literal. Stahl lives in the cottage known as Candlelight, which artist Maud Briggs Knowlton and her husband, Edward, built on Monhegan Island in 1921. He is also the curator of “A Life Made in Art: Maud Briggs Knowlton,” on view at the Monhegan Museum of Art and History, July 1 through September 30.

“My curiosity [about Knowlton] developed about 16 years ago, when my wife and I bought her house…I knew her name and knew a little bit about her art, but [I then] began a sort of quest to learn more about her and to actually start a collection of her work.” Within a few years, Stahl (who is now associate director of the Monhegan Museum as well as director of the affiliated James Fitzgerald Legacy) pitched the idea of an exhibition to Monhegan Museum director Ed Deci, who was enthusiastic but concerned that there might not be enough material. So Stahl set out to solve that problem by going right to the source.

Although Knowlton started her artistic career as a china painter and designer and went on to become an acclaimed watercolorist, the apex of her professional life was as the first director of the Currier Gallery of Art in Manchester, N.H. (now the Currier Museum of Art, which will host the exhibition February 15 through May 10, 2020). Hired in 1929, she was one of the first three or four women to hold this lead role in any major American art museum. Stahl reached out to the Currier’s then-director, Susan Strickler, who embraced the project as her own. “Susan Strickler has been amazing,” says Stahl. “[It became] a mission for Susan to learn as much as she could, and she did a wealth of research.”

Part of that research was identifying works by Knowlton in other collections. The Currier and the Monhegan Museum each had a cache – the latter also in possession of a substantial archive of photographic works by her husband Edward Knowlton – but there were very few works in other public collections. This was disappointing, but not particularly surprising. Even today, statistically speaking, museums collect more artwork by men than women, but in Knowlton’s time this gender gap was even more pronounced. In fact, associated as she was with the stereotypically female art of china painting, and with various applied Arts and Crafts movements, she would probably never have even been considered by most major collecting institutions of her day.

It’s true that she painted china. But it’s not true that this was some sort of genteel hobby, a way for privileged women to pass the time. China painting was a full-fledged industry in turn-of-the-century America, with factories producing “blanks” to be painted, workshops of trained artisans doing the painting, and designers, like Knowlton, developing and publishing carefully delineated plans for craftspeople to follow. Knowlton had several designs published in Keramic Studio, the leading publication on ceramics decoration, one of which is in the show, and she also developed what may have been proprietary designs for her own work. Included in the show is a large black pitcher with a pair of absurdist dragons writhing across its belly, as well as a Limoges hair receiver decorated with gold-rimmed cartouches of forget-me-nots, both from the Currier’s collection.

These ceramic pieces were produced around the same time that Knowlton was brought on, in 1901, as a founding instructor at the brand-new Manchester Institute of Arts and Sciences (now the Manchester Institute of Art). There, Strickler writes in her excellent catalog essay, Knowlton first taught drawing and watercolor but then expanded her expertise by continuing her own education at the Society of Arts and Crafts and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, both in Boston, taking classes in metalsmithing, printmaking and more. She received official “Craftsman” designation in both metalwork and china decoration, an imprimatur that placed her within the upper echelons of the American Arts and Crafts movement.

By this time Knowlton and her husband had already been visiting Monhegan Island, 12 miles off the coast of Midcoast Maine for several years. It’s not known precisely when they first visited and how they thought to go there – Monhegan was not yet the flourishing art colony that it would come to be in the Twentieth Century, and there was only one small inn – but it’s possible that art connections brought them there. Alice Swett, a Boston-area art teacher, was a friend both on and off the island; another connection might have been Samuel Peter Rolt Triscott, a watercolorist and photographer who lived on Monhegan year-round but frequently exhibited in the Boston area. Indeed, Knowlton’s husband, Edward, was a gifted amateur photographer, and if he had seen any of Triscott’s photos on the mainland he might have been inspired to visit the place that they depicted.

What is clear is that both Knowltons cherished in Monhegan the qualities that many other artists have ever since: a sense of escape from the hustle and bustle of modern life (the Knowltons named their house Candlelight because it had no electricity); ample opportunity for artistic inspiration in its dramatic headlands, tall pine woods, ramshackle fishing shacks and colorful cottage gardens; and a small but thriving community of people who treasured the same things. In addition to Swett and Triscott, the Knowltons’ time on Monhegan overlapped with that of art luminaries George Bellows, Robert Henri, Rockwell Kent, Edward Hopper and many others. It is not clear to what extent the Knowltons interacted with Henri’s crowd – given the size of the island and the limited lodging, they must have to some degree – but it is possible to see their influence in Maud Briggs Knowlton’s painting. Her “Summer Surf” of 1927 “is so fluid,” says Stahl, “with no graphite underdrawing – very freeform, and brilliant colors”; an expression in watercolor of what those better-remembered artists were doing with oils.

But views of the surf and the headlands were rarities in Knowlton’s oeuvre. Her first love was the gardens of Monhegan. (And visitors to the island today can see and enjoy gorgeous perennial gardens again, after a non-native deer herd was eliminated in the late 1990s.) Her watercolors of Monhegan’s cottage gardens are a delight to the eyes but also to local historians like Stahl, who can identify each building pictured (Triscott’s house, right next door to Candlelight, was a favorite subject), name its inhabitants throughout history, and even identify plantings that have come and gone with the years and the deer.

It’s a surreal thing to speak to Stahl on the phone as he is standing in the home that Maud and Edward Knowlton lived in together, knowing that he talks about what she could see from her window. There is no guesswork involved. One of Stahl’s favorite paintings is “Flowers at the Window, Candlelight,” a view from inside the house. There are no known watercolors of the Knowltons’ own garden – somewhat surprising, since, as Stahl notes, Edward was an avid gardener, remembered still for planting a hedge of beach roses that continues to flourish on Lobster Cove Road. But “Flowers at the Window” shows what must have been the late-summer bounty of the Knowlton garden, placed on the sill of the large, north-facing studio window. Stahl has fond words for that “beautiful north studio window that gives all this indirect light.”

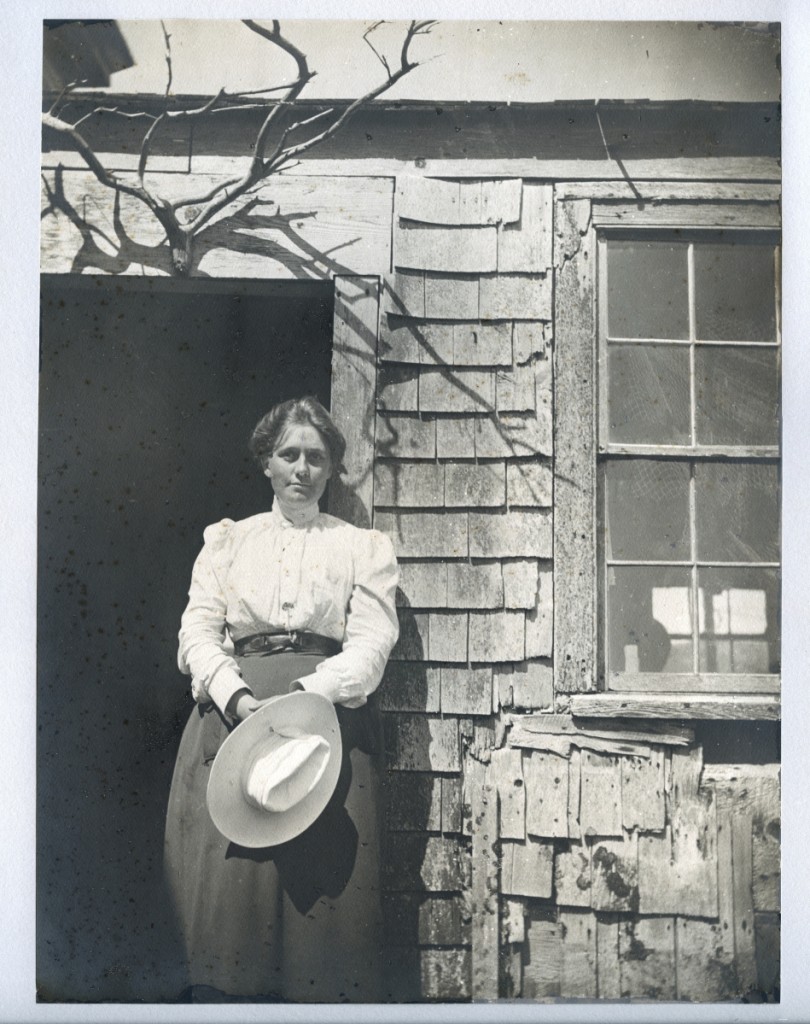

“Maud Briggs Knowlton” by Edward Knowlton, circa 1897. Gelatin silver print. Monhegan Museum of Art & History, gift of Leo and Bernice Meissner.

Maud was the professional artist, the scholar, the teacher and the art-world leader, and the exhibition is very much about her. But some space has also been set aside for Edward’s photographs, showing his very different vision of Monhegan. Where Maud loved tidy houses and gardens and sometimes the surf, Edward loved to shoot the falling-down fishing shacks near the pier, along with the people who made their living there. To Twenty-First Century eyes, the shot of lobsterman Benjamin Davis looking out to sea with his binoculars, framed by the tools of his trade, seems impossibly quaint, as if it must have been posed – but these were the real people of the (largely) pre-tourist Monhegan, and Edward Knowlton’s photographs are valuable records of that time and place.

As photo scholar Susan Danly writes in the catalog, in these relatively early days of photography – where the machinery and the chemistry were both complex – Edward probably had only a limited capacity to make photographic prints while the couple was on the island. This is probably why he experimented with cyanotype, a blue-tinted image that requires only a chemically treated sheet of paper, light and the sun. Candlelight may have housed a makeshift blackroom, but for the most part Edward probably made his exposures on the island and had them printed back in Manchester, where he continued to have a full-time job as a factory paymaster. The Monhegan Museum was lucky to receive some 150 of his original glass plate negatives, and several hundred prints, shortly after its founding, as a gift from the artist Leo Meissner (though how exactly Meissner happened to own them is something of a mystery). They form a core of the museum’s collection of historical island photography today.

Stahl marvels, to some extent, at the Knowltons’ personal and creative partnership, observing that Maud really “had the premier professional role in this marriage,” unusual at the time, with her career determining their travel, their activities and their friendships (the Knowltons did not have children). “He loved her dearly,” says Stahl, mentioning the text of a letter, transcribed in the catalog, in which a 101-year-old Edward speaks of his enduring love for Maud, who had passed away six years before. The art that they produced, if not together then in tandem, is a lasting record of that long, loving and mutually supportive relationship in which they were both able to flourish. “It was part of the partnership of their marriage and also of their whole philosophy of how they lived – how they gardened – and how they created,” Stahl says. “Creativity was a huge part of their lives, and it was primarily expressed on Monhegan.”

The Monhegan Museum is at 1 Lighthouse Hill Road. For information, 207-596-7003 or www.monheganmuseum.org.