“On the River” by Frederick Carl Frieseke, 1908. Oil on canvas. Collection of Carolyn A. and Peter S. Lynch. Photography by Bob Packert/Peabody Essex Museum.

By Laura Beach

SALEM, MASS. – Even if they do not know him by name, many Americans will recognize Peter S. Lynch as the former television spokesman for Fidelity Investments, where he was best known for managing the company’s wildly successful Magellan Fund between 1977 and 1990. In collecting circles, the wiry Bostonian with a distinctive shock of white hair has long been admired for the trove of American paintings and decorative arts he gathered over half a century with his wife, Carolyn, who died in 2015.

The Lynches’ collection and the way they lived with it in their residences in Marblehead, Boston and Scottsdale are the subject of “A Passion for American Art: Selections from the Carolyn and Peter Lynch Collection.” Selections from the trove are publicly on view for the first time at the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) through December 1.

Dean Lahikainen, the museum’s Carolyn and Peter Lynch curator of American decorative art, recalls, “The Lynches had long been involved in the institution. Carolyn joined PEM’s board of overseers in 1994 before becoming a trustee in 1997. My association with them really began when PEM asked Carolyn to form the first visiting committee for the American decorative arts department in 1998.” Lahikainen, who organized the show and edited its associated catalog, enlisted help from PEM curators Austen Barron Bailly, Sarah N. Chasse, Karina H. Corrigan, Daniel Finamore, Karen Kramer and Lan Morgan. Jeanne Schinto contributed a catalog essay on the collectors. The Lynches first warmed to the idea of a show after PEM exhibited Dutch golden-age paintings from the collection of their friends and fellow Marblehead residents Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo. Peter turned again to the project in 2016 as a way of honoring his late spouse.

A Passion for American Art recounts the history of the collection from its inception around 1970, when the young couple began furnishing their home and giving each other antiques as gifts. Over time, their interests, initially centered on maritime and coastal paintings and New England decorative arts of the Eighteenth and early Nineteenth Century, grew to encompass a select group of Modern and contemporary art and design.

“What strikes me most about the collection is the way it was influenced by location and by the people the Lynches encountered over the course of their lives,” Lahikainen says of the diverse, nuanced array that creates a portrait of the couple’s life together.

Peter Lynch, now 75, was born in Newton, Mass. His father, a Boston College mathematics professor, died when Peter was ten. In his 1989 book One Up on Wall Street, written with John Rothchild, the investor explains that his youthful employment as a golf caddy led to a scholarship to Boston College as well as to an introduction to D. George Sullivan, chief operating officer of Fidelity Investments. Peter joined the company after interning there in 1966 and continues to work part time as vice chairman of Fidelity Management & Research Company, an advisory arm of Fidelity Investments.

Lynch met his wife, a Pennsylvania native, while he was earning an MBA at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. They married in 1968 and two years later moved to Marblehead, on Boston’s North Shore. Country furniture and blue and white Chinese export porcelain were among their first antiques, Lahikainen writes, noting, “The Lynches fell in love with old Marblehead and embraced its rich history, most notably by collecting Marblehead Pottery and the work of local artist J.O.J. Frost.”

By 1974 the Lynches owned Marblehead’s Colonel William Lee house, a pre-Revolutionary war structure built for wealthy merchant Robert “King” Hooper. Their dedication to restoring the historic property caught the eye of Fidelity chief Edward C. “Ned” Johnson III, who encouraged his young associate to join the board of what is now Historic New England in 1975. This in turn introduced the Lynches to Bertram K. and Nina Fletcher Little, whose passion for American folk art played a decisive part in the Lynches development as collectors.

Three treasures once owned by the Littles are signal works in the PEM display. The first is “The March into Boston from Marblehead, April 16, 1861: There Shall Be No More War,” Frost’s panoramic depiction of Marblehead volunteers departing for the Civil War, a conflict from which the artist’s father would not return. Painted on Masonite in 1925 and measuring 72 inches wide, the much exhibited work, a favorite of Nina Little’s, fetched $486,500 at Sotheby’s first sale of Little property in January 1994. The painted Hadley-style chest that was made between 1712 and 1722 for Esther Lyman of Northampton, Mass., most likely for her 1724 marriage, went to the Lynches for $354,500, a record for a blanket chest, in the same sale. Nine months later, at Sotheby’s second auction of Little property, the Lynches claimed a late Eighteenth Century paint-decorated chest-on-chest attributed to the Dunlap family of New Hampshire cabinetmakers for $310,500.

In 1982, the Lynches purchased a rare International Style house designed in 1938 for Howard A. Colby by Royal Barry Wills, a Boston architect better known for his Cape Cod-style designs. They set about transforming the waterfront property, making it a sympathetic space for exhibiting their growing collection. As Lahikainen details, they created six “period rooms” using Eighteenth Century woodwork, period hardware and old wideboard flooring. The most memorable space is the keeping room, a 1985 addition modeled after one the Lynches admired at Cogswell’s Grant, the Little’s house in Essex, Mass.

-1024x656.jpg)

The Lynches displayed maritime paintings and coastal views in the East Room of their Marblehead Neck house. A treasure of the collection is “Among the Ice Floes,” center, by William Bradford. The oil on canvas of 1878 hangs above a circa 1810 caned settee, possibly from the shop of Duncan Phyfe. It is flanked by groupings of Eighteenth Century furniture from Philadelphia and Boston. © Peabody Essex Museum. Photography by Kathy Tarantola.

The Marblehead Neck house became the setting for what is most distinctive about the Lynch collection, early American furniture, much of it from Massachusetts, and maritime paintings and coastal views. Commemorating the era of Arctic exploration, the great William Bradford painting “Among the Ice Floes,” 1878, hangs above a caned settee that may be from the shop of Duncan Phyfe. Nearby is a choice view of the Massachusetts coast by John Frederick Kensett, as well as works by Albert Bierstadt and other leading Nineteenth Century American landscape artists.

Marblehead Neck was also where the Lynches began collecting studio furniture and ceramics. As Schinto explains, an invitation to join the Seminarians, an exclusive collectors’ group, led to an introduction to woodworker Sam Maloof and ceramist Otto Natzler. The Lynches eventually acquired around 40 ceramics by Natzler and his late wife, Gertrud. Maloof made 25 pieces of furniture for the Lynches, much of it for their Scottsdale vacation house.

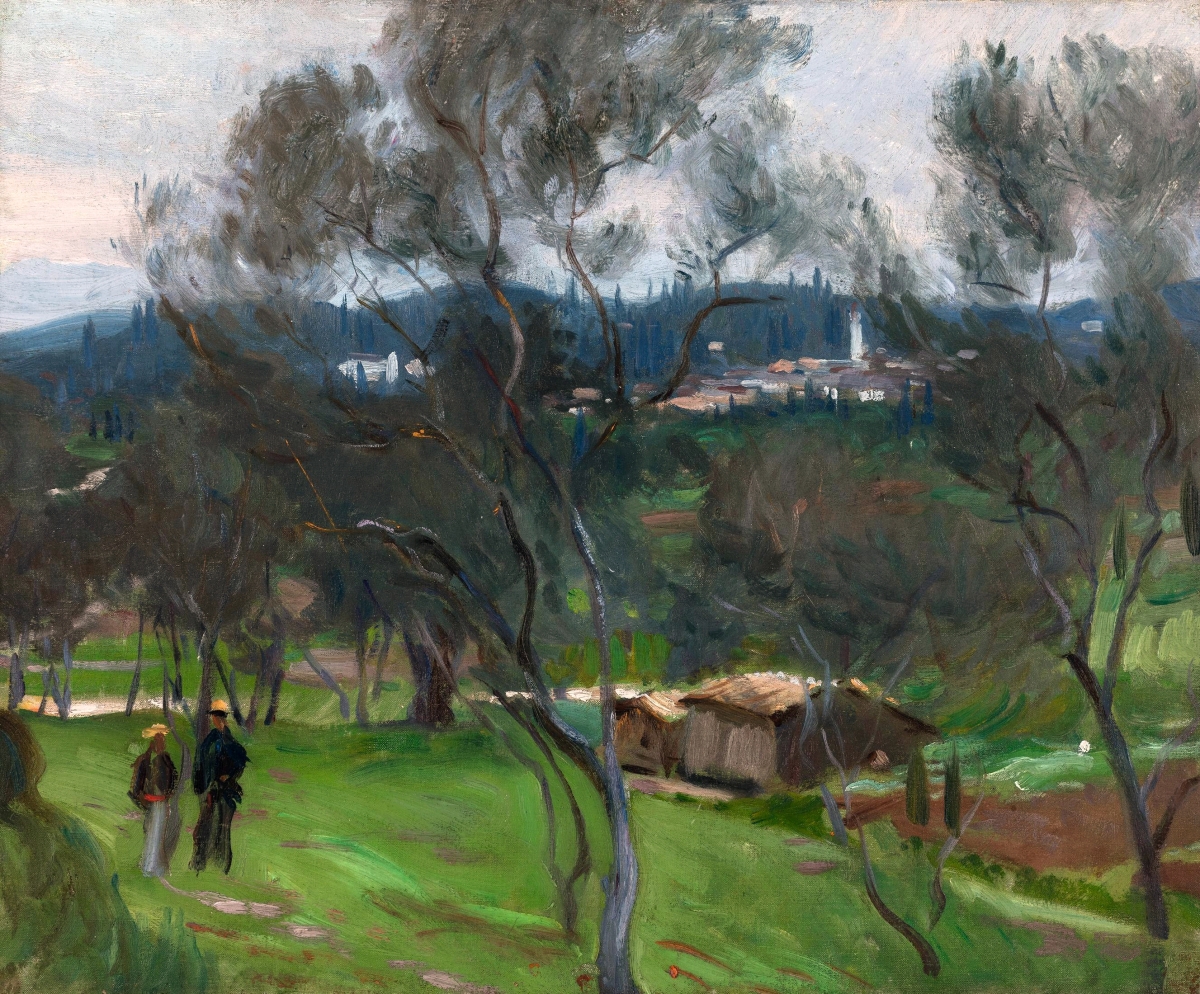

Their children grown, the Lynches began spending more time in Boston, where they remodeled the fourth and fifth floors of two joined 1860s stone mansions at the corner of Arlington Street and Commonwealth Avenue overlooking the Boston Public Garden. They appointed the grand space with a cosmopolitan assortment of art and antiques, including exotic South American views by Martin Johnson Heade and a tranquil Giverny portrait by Frederick Frieseke, as well as important examples of New York and Philadelphia furniture.

Featuring 25 paintings, 125 pieces of decorative art, much of it ceramics, and 51 pieces of furniture, the exhibition is installed in the Peabody Essex Museum’s first-floor Putnam Galleries, which formerly housed the museum’s maritime paintings collection. Though the exhibition’s main emphasis is on the objects themselves, five vignettes – or “Collector Moments,” as PEM is calling them – allude to the Lynch residences and give visitors a sense of the couple’s rapport with objects.

One intriguing vignette draws from the dining room of the Marblehead Neck residence, where the Lynches displayed a 1790-1800 sideboard, unique in form and decoration, by Stephen Badlam (1751-1815) and a related tray that is stamped twice with the names of Badlam and Abiel White (1766-1844). Both sideboard and tray have what Lahikainen describes as a wavy gallery around the edge of the top, a device meant to secure glassware.

“Boston Harbor” by Thomas Chambers, about 1843-51. Oil on canvas. Collection of Carolyn A. and Peter S. Lynch. Photography by Bob Packert/Peabody Essex Museum.

“Around every corner is a great work of art,” Lahikainen says of the PEM show. Among the paintings, there is Childe Hassam’s commanding 1911 canvas “East Headland, Appledore-Isles of Shoals,” a star of PEM’s 2016 exhibition “American Impressionist: Childe Hassam and the Isles of Shoals”; Winslow Homer’s “Grace Hoops,” an oil on canvas of 1872 that is a paean to “rural life and youth,” writes curator Austen Barron Bailly; and Fitz Henry Lane’s 1865 “View of Gloucester Harbor,” marking a pivotal moment in the artist’s career.

An authority on Massachusetts furniture of the Federal and Classical era and the author of Samuel McIntire: Carving an American Style, Lahikainen speaks admiringly of an elegant serpentine-form dressing table attributed to Nehemiah Adams (1769-1840), a Salem, Mass., cabinetmaker. “It has the thinnest, finest legs,” the curator says of the piece, as graceful as a Balanchine dancer en pointe.

Purchased by the Lynches from Israel Sack, Inc, in New York, a piecrust tea-table from the shop of Salem cabinetmaker Nathaniel Gould of Salem is a rare New England example of the form and was in PEM’s 2014-15 exhibition “In Plain Sight: Discovering the Furniture of Nathaniel Gould.” Lahikainen writes, “This piece is the finest extant Salem stand table known and one of the true gems in the Lynch collection.”

After 2000, the Lynches embarked on a new project in the Arizona desert. One senses in the bright, open spaces and earth-tone palette of the property, completed in 2005 but recently sold, a release from the collecting impulse that occupied them in the 1980s and 1990s. Accented with Navajo weavings, Pueblo pottery and Chihuly glass, as well as with an O’Keeffe oil and a Calder gouache, the main house showcases a suite of Maloof furniture created in partnership with the craftsman, by then a friend of the family. Maloof used a handsome slab of figured walnut he had been saving for a special project for the couple’s dining table. To go with the table he made ten walnut spindle-back chairs – all on view at PEM but displayed at different angles to convey the beauty and subtlety of the craftsman’s designs.

“Maloof worked and worked to refine every contour. Having sat in the chairs, I can tell you they are wonderfully comfortable,” says Lahikainen. In selecting pieces by Maloof, the Lynches completed the circle that began with their first love of the beautiful wood and fine craftsmanship of early New England furniture.

Late last year, Peter Lynch gave three paintings to PEM in honor of his wife: Hassam’s “East Headland, Appledore-Isle of Shoals,” Frost’s “The March into Boston from Marblehead, April 16, 1861: There Shall be No More War” and Georgia O’Keeffe’s “Cedar and Red Maple, Lake George” of 1921. As the chapter closes on a collecting project that, as Lahikainen puts it, grew from “intellectual curiosity, love of people and ultimately from the places they chose to call home,” one cannot help but wonder what comes next.

A Passion for American Art: Selections from the Carolyn and Peter Lynch Collection is published by the Peabody Essex Museum and distributed by University of Massachusetts Press. The book provides insight into the couple’s motivations and taste by presenting 11 rooms from three of their residences.

The Peabody Essex Museum is at East India Square. For more information, 866-745-1876 or visit www.pem.org.

.jpg)